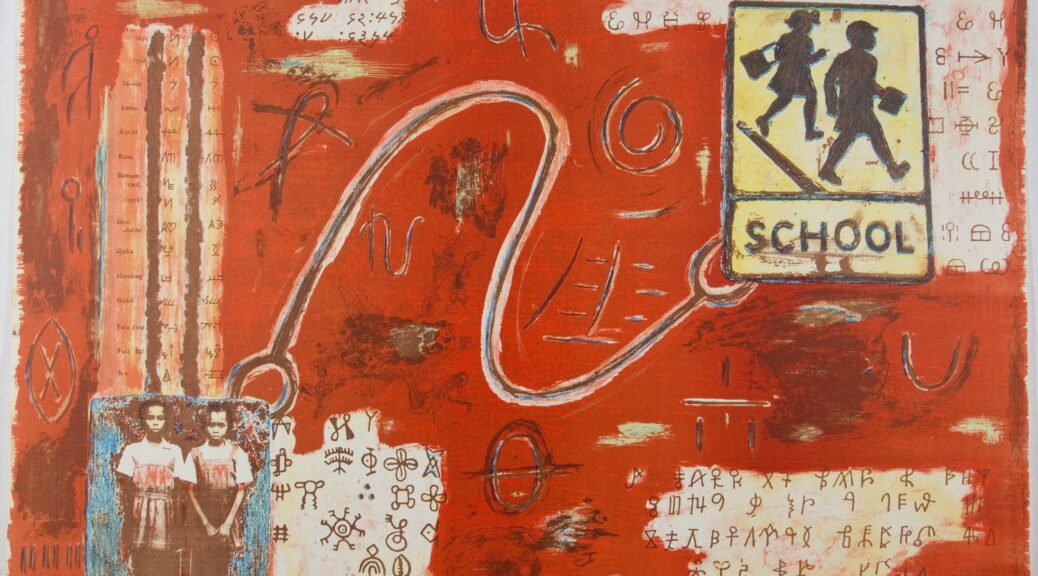

We recently talked in specific about a project to work on a proactive strategy to diversify our collections. That piece focused on the expansion of Black Lives Matter materials in our holdings, and was a great practical introduction the sort of work being done by professional staff to account for past inequities in how we acquire materials. The umbrella effort for that project was spearheaded by Carolyn Cunningham, the Libraries’ Head of Collection Development, who shares her perspectives on the comprehensive work to diversify the Libraries’ collection here.

As the diversity and inclusion work done on UT campus continues to grow and gather steam, it has been helpful to have UT Libraries commitment to inclusivity, diversity, equity and accessibility (IDEA) as a guiding star for our work in the Scholarly Resources Division (SRD).

The liaison librarian team in SRD recently had the opportunity to talk with library colleagues about how IDEA informs our collection development work, and how we support others in their collection development work. Our team members are Carolyn Cunningham, David Flaxbart, Corinne Forstot-Burke, Bill Kopplin, Susan Macicak, Katy Parker, and Shiela Winchester. The team is committed to using an IDEA lens in all of our work, beyond special projects or short-term initiatives. This means that we approach every request for a book, every new product offer, and every decision about how to use collection funds with the frame of mind that we will strive to include diverse voices in our collection and orient ourselves toward finding and making available resources that include the many experiences and perspectives of our campus community and beyond. The team describes this work as a group effort, and we continuously learn from each other.

This embedded IDEA orientation is important because the academic publishing landscape does not necessarily represent all the voices that we want to include. The team recently looked at the results of the 2019 Diversity Baseline Survey together. This survey looked at diversity in the publishing industry, which included academic publishing participants. The respondents to this survey were 76% white, 97% cisgender, 81% heterosexual, and 89% non-disabled. For a quick point of comparison, 38.9% of UT students and 75.7% of UT professors are white. As the creators of the survey point out, “If the people who work in publishing are not a diverse group, how can diverse voices truly be represented in its books?”

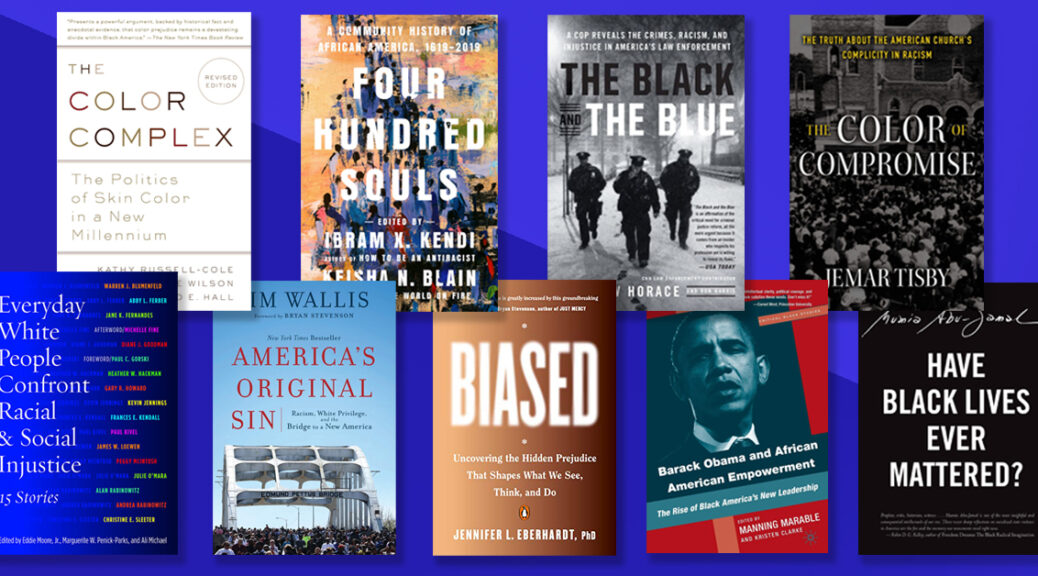

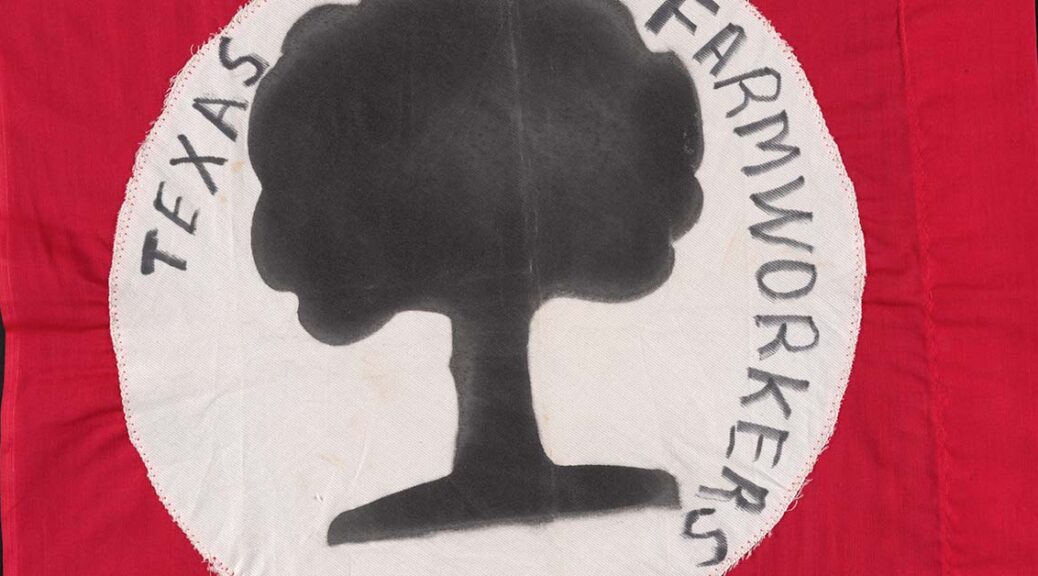

Publishers are not the only influencers of what we add to our collections. User requests and emerging research areas are an important source of data for us. One exciting area of focus this past year has been strengthening our holdings related to the Black Lives Matter movement, civil rights, and anti-racism topics. Bill Kopplin, social sciences librarian and coordinator, has compared our collections against peer libraries, kept an eye on campus reading clubs and resource lists, and worked directly with vendors to do a wide-ranging scan of publications in these areas to consider adding to our collection. I can also point to the strong interdepartmental work of facilitating selection and discovery of important resources via catalog notes and subject headings. Folks from across UT Libraries work together to select and make available the U.S. Latinx LGBTQ Collection and Black Queer Studies Collection with local notes in our library catalog. This kind of focused attention is found throughout the work of our subject librarians, and our team is here to help get new efforts off the ground.

One programmatic aspect of collection building that our team works on closely is the major approval plans. These plans are arrangements with large vendors to automatically send us certain types of books published by essential publishers. We keep an eye on those plans to make sure they are bringing in the right material. By describing this process with words like “arrangements,” “large,” and “automatically,” I want to illustrate that it is easy for up-and-coming authors and small publishers to get left out. This is where the expertise of our knowledgeable subject librarians, as well as input from our users, comes in. While we aim to collect books that our researchers expect us to have from major publishers, we pay close attention to the requests we get from users through interlibrary loan, through our Suggest a Purchase form, and via our library colleagues. Those data tell us which things are missing from the collection. We also use these requests to update ourselves on new terminology, new classes being offered, and new and enduring research topics that are finding an audience on campus.

This work takes a village, and we will continue to learn from each other and respond to new opportunities to make our collections meet the needs of our current and future users.

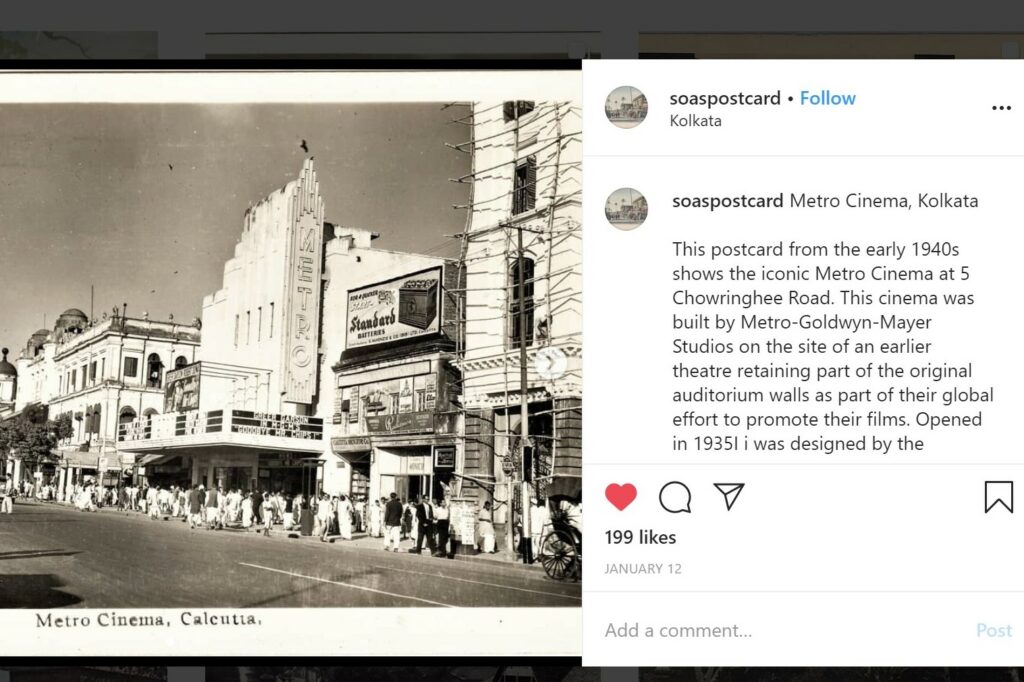

Discover more of the diverse collections at the Libraries through our Instagram series, Highlighting Diverse Collections.

- Black History Month: https://www.instagram.com/p/CKwYL7wlgBt/

- Complexities of Race: https://www.instagram.com/p/CEjkgPilUVd/

- National Hispanic Heritage Month: https://www.instagram.com/p/CEjkgPilUVd/

- World Autism Month: https://www.instagram.com/p/CNIBDhiFI86/

- Cookbooks from Around the World: https://www.instagram.com/p/CSw3WmzFXb6/

This post originally appeared at the blog of the Diversity Action Committee.