Digital Humanities Workshop

Introduction to Recogito

When: 3/8/24, 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm

Where: Zoom

Presenters: Miriam Santana and Willem Borkgren

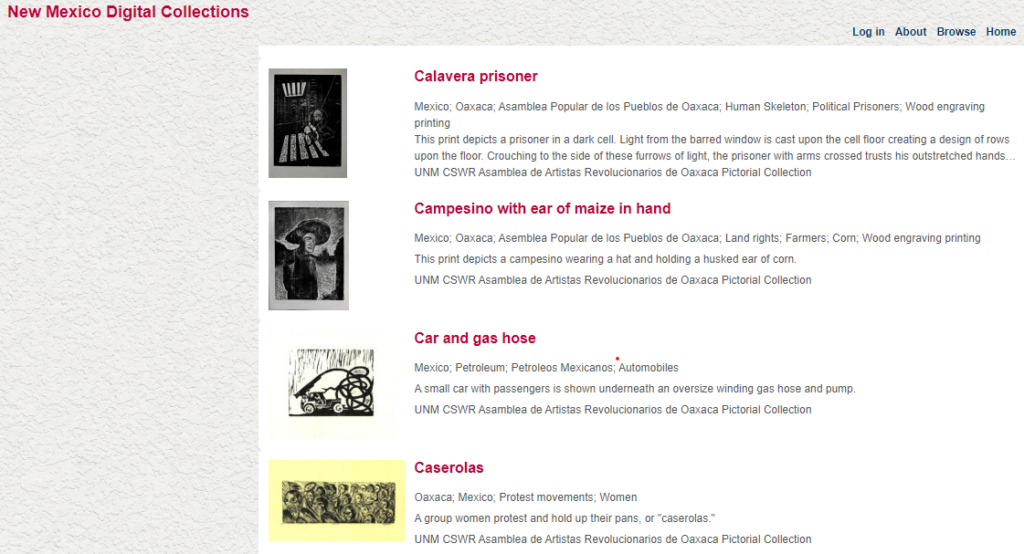

Recogito is an open-source semantic annotation tool that allows you to tag key terms and reveal the relationships between key names, places, and events between multiple documents. Attendees will learn how to create an account, upload documents, and start working on tags and annotations. They will also learn the deeper capabilities of Recogito, such as mapping relationships, working collaboratively on a corpora of documents, and exporting data for use in other DH tools.

Introduction to Optical Character Recognition (OCR)

When: 3/22/24, 12:00 pm – 1:15 pm

Where: Hybrid – Zoom and Scholars Lab Data Lab, Perry-Castañeda Library

Presenters: Dale J. Correa, Mercedes Morris, & Natalya Stanke

This workshop introduces the basics of optical character recognition (OCR), which allows for full-text searching and other types of text manipulation of a digitized document. Attendees will learn how to use Google Docs to create a basic machine-readable text from an image file and be introduced to Tesseract for OCR through exercises in Google Colab.

This workshop is open to researchers interested in OCR for any language. It is strongly recommended that attendees:

1) prepare a digitized, highly legible sample image file for trying out the tools

2) have a Google account to do the exercises fully and save their work.

Register for Zoom or PCL Scholars Lab Data Lab

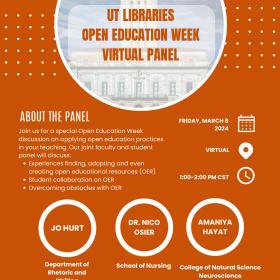

Open Education Week Virtual Panel

When: 3/8/24, 1:00 pm – 2:00 pm

Where: Zoom

UT Austin’s OER Working Group invites you to celebrate Open Education Week (March 4-8) by joining our faculty/student panel for a virtual discussion on open education practices. Join us for a special Open Education Week discussion on applying open education practices in your teaching. Our student/faculty panel will discuss their experiences finding, adopting, and even creating open educational resources (OER) and other no-cost course materials.

In addition to this faculty perspective, our panel will also include a student voice. Our student panelist is currently collaborating on an original OER project, bringing valuable and unique insight into how open pedagogy can transform student learning experiences.

Digital Scholarship in Practice

When: 3/8/24, 1:30 pm – 2:30 pm

Where: Scholars Lab Data Lab, Perry-Castañeda Library

Want to get started with Digital Humanities in the classroom, but you don’t know where to start? This introductory workshop will provide advice and practical ideas to incorporate digital humanities methodologies at all levels of teaching — from syllabus design to assignments and classroom activities. Learn about platforms, strategies, and resources to fit your classroom, your teaching style, and your comfort level with technology. While the advice given will apply to a wide variety of classrooms, the workshop will highlight resources specific to Japanese and East Asian Studies.