This commentary appeared in the Houston Chronicle, August 26, 2017.

Ask what the campus library does and many will say, “It provides access to books.” Looking toward the future, if libraries are to succeed, they will need to increase investment in services that extend beyond such user assumptions. Libraries should invest in virtual spaces that complement existing technology, unique collections, and content expertise, and library space as a concept will need to be redefined to accommodate work in new arenas.

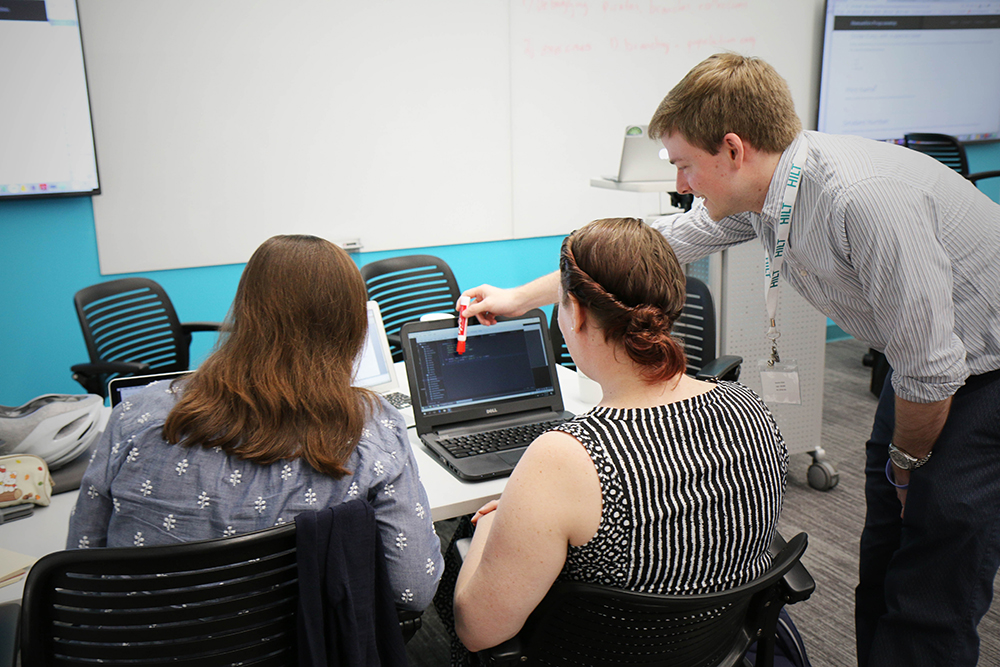

In a 2015 AACU survey employers reported that they believe only 27 percent of recent graduates are proficient at written communication and even fewer are “innovative/creative”. When thinking about this in concert with student impressions of campus technology in a 2016 ECAR study, the library must contribute to both creative and deepened use of technology in the classroom. Leading students into virtual environments to create research products, utilizing classrooms designed with multiple screens for active small group work, and helping students manage work with the use of project management tools all present opportunities for rich collaborative teaching partnerships between librarians and faculty.

It’s also important for libraries to invest in infrastructure to support web publishing platforms, virtual reality, makerspaces, and large visualization walls that complement existing university resources. Integrating these technologies into the classroom experience will challenge us all to think in new ways about where and how learning occurs. Libraries can provide support to students and teachers as they engage with, critically examine, and build community in and around these spaces. But in order for this to occur, a shift in the way people conceptualize library spaces and services has to occur. By working in new environments, libraries can help students improve communication and develop critical thinking and digital literacy skills that will serve them in all areas of their lives.

In order for us to be successful, campus level administrators have to provide a seat at the executive table for library leadership. Increasing the visibility of challenges being faced by libraries sheds light on the complexity of our current operating environments. Sharing information about the value of library services, and about staffing and IT infrastructure needs, provides an opportunity for those that are invested in the library to ask questions about future directions and provide input on anticipated needs.

Libraries are increasingly becoming key testing grounds for innovative classes and research projects that take advantage of emerging technologies. Administration can demonstrate support for these innovative faculty-library collaborations by providing financial, administrative, and moral support for departments that are attempting to reinvigorate the curriculum. Libraries are not operating in the same way that they were five years ago, and it is imperative that administrators see and fully understand the ways in which our services are evolving, and the ways in which our services provide pathways for new ways of teaching and learning.

Library leaders, similarly, need to fully understand the challenges faced by library staff as they revise organizational and operational models to accommodate new working environments. By providing services in hybrid environments, libraries are demonstrating their capacity to play a key partner role in the teaching and learning process in higher education. This role can advance the critical inquiry and discourse skills of our students, and can contribute to student success post-graduation.

So much of what we think about when we think about our students after graduation is focused on success in the workplace, but at a higher level, many in academic communities are concerned with the development and evolution of civil society. As we expand library services more and more into virtual spaces, we will increasingly ask our communities to redefine their understanding and expectations of our role in developing capacity to engage in dialogue. By investing in the changing landscape of libraries, we are also inviting them to adapt to the ever-evolving landscape of communication and civic engagement.

Amber Welch is the head of technology enhanced learning for The University of Texas Libraries.