Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the UT Libraries Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of, and future creative contributions to, the growing fields of digital scholarship.

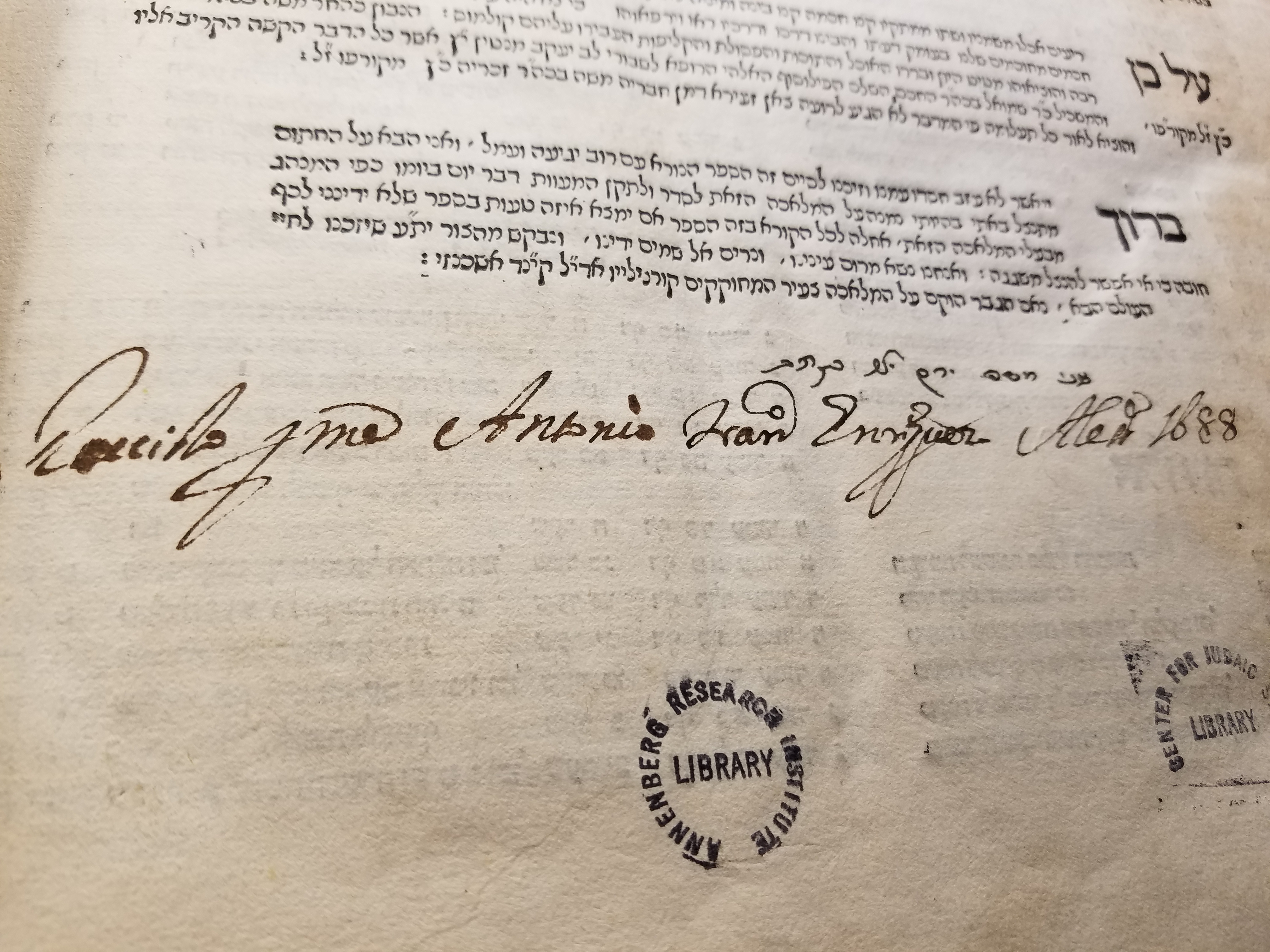

The E-lijah Lab (text in Hebrew) is a digital humanities lab in the Department of Jewish History & Bible Studies at the University of Haifa in Northern Israel. Among many projects that map the history of Jewish culture, HaMapah (Hebrew for ‘The Map’), founded in 2018 by then PhD students Elli Fischer and Moshe Schorr (now a Rabbi and a software engineer respectively), “aims to bring modern tools of quantitative and geographic analysis to Rabbinic literature[1].” Mapping ‘rabbinic networks’ that are based on responsa (Jewish legal texts written in the framework of questions and answers), the project reveals new data that “shows spheres of influence through time and across space.”

Schorr explains that “a true responsum, the answer that a rabbi writes to a query posed by another rabbi, is the basic unit of rabbinic authority. It orders the two correspondents hierarchically; the one asking acknowledges the greater expertise of the one answering, thereby expanding the latter’s influence.” Moreover, “because the hierarchy is … emerging implicitly from the deference of the secondary and tertiary elite, it can tell us more about the dynamics of influence, reputation, and expertise than many other forms of legal authority.”

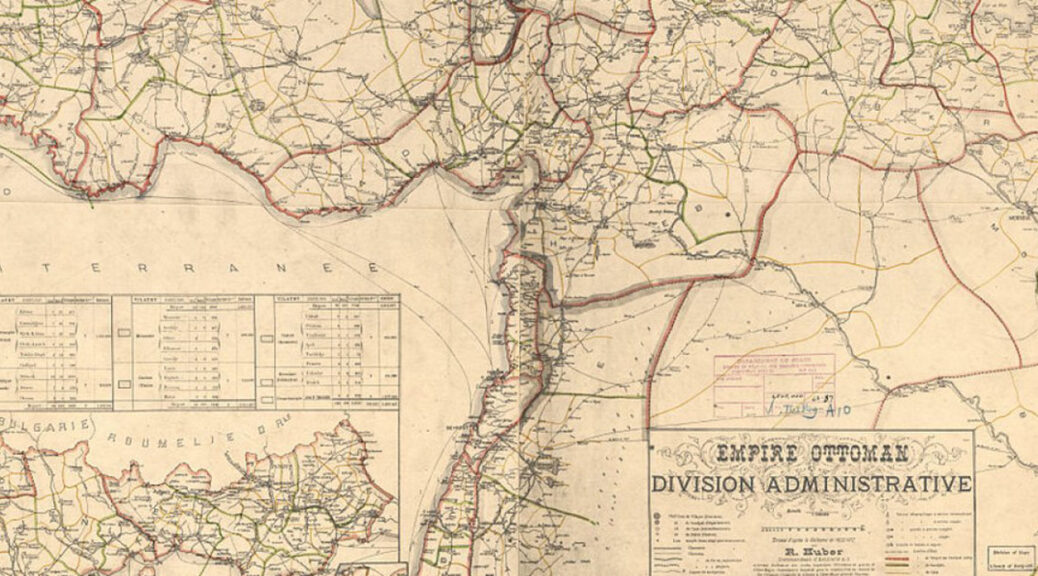

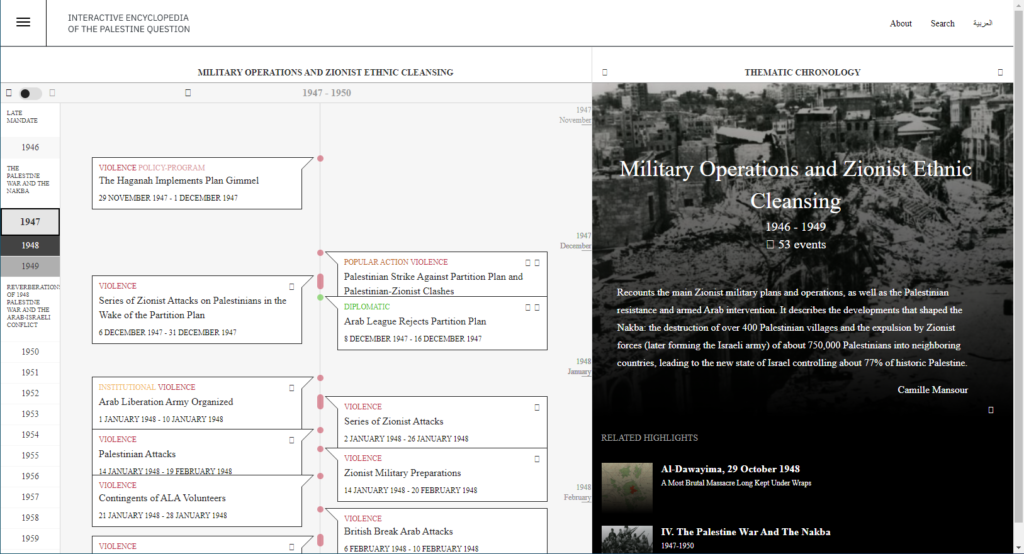

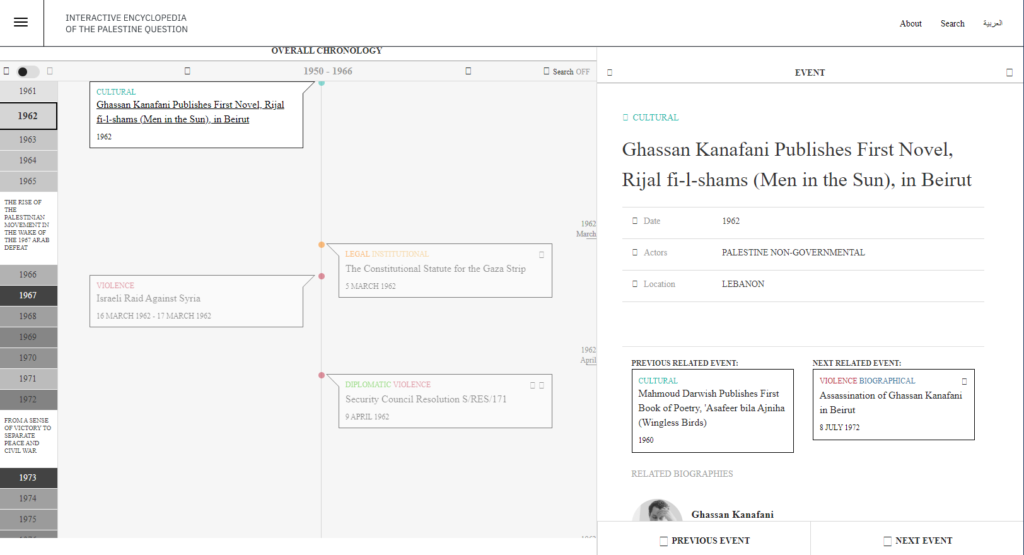

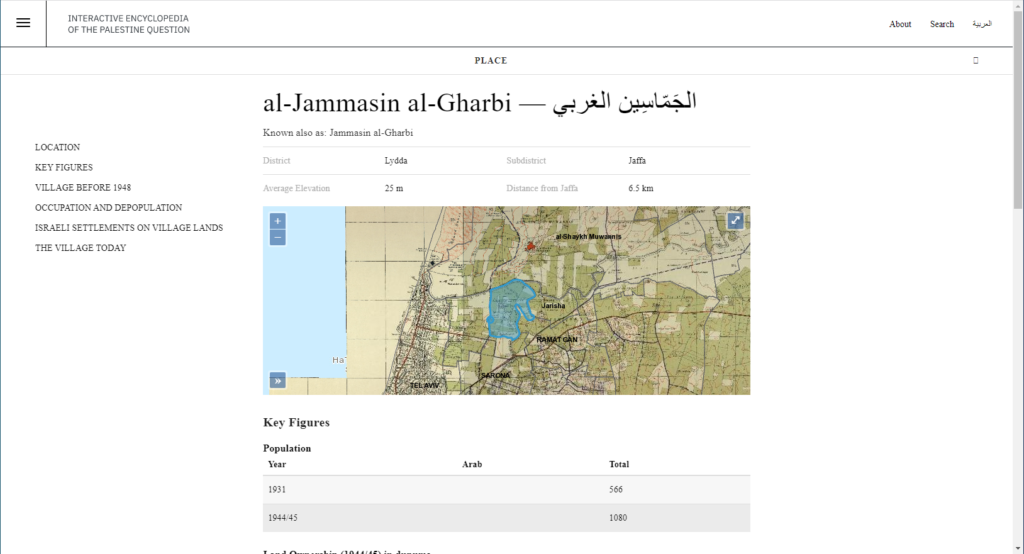

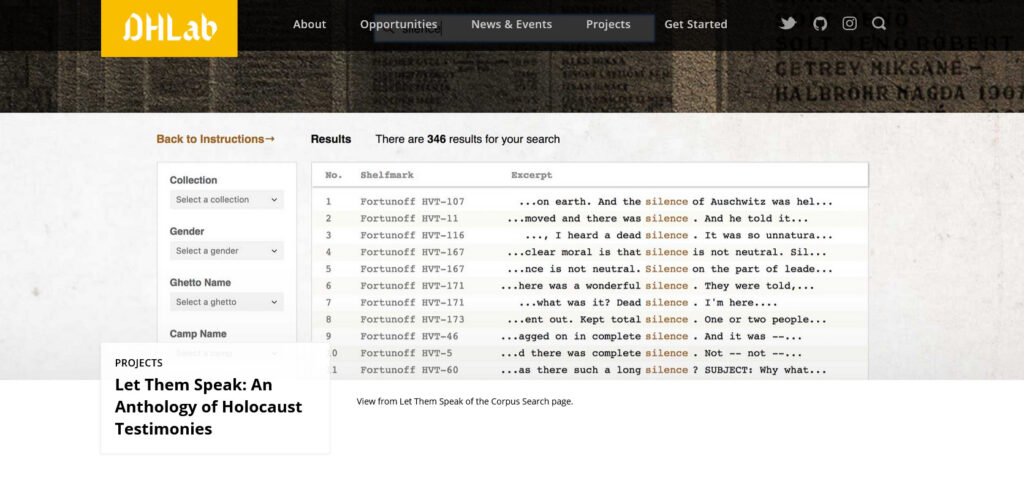

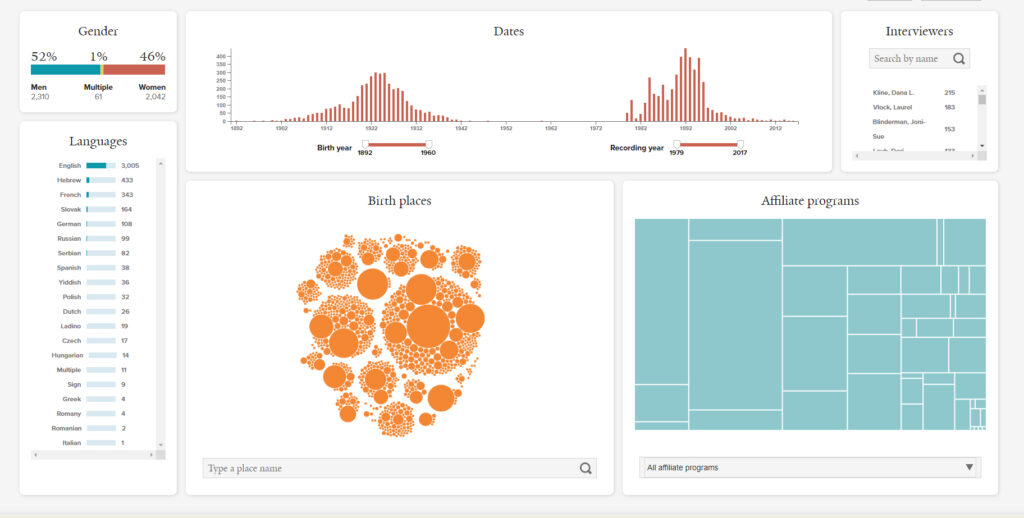

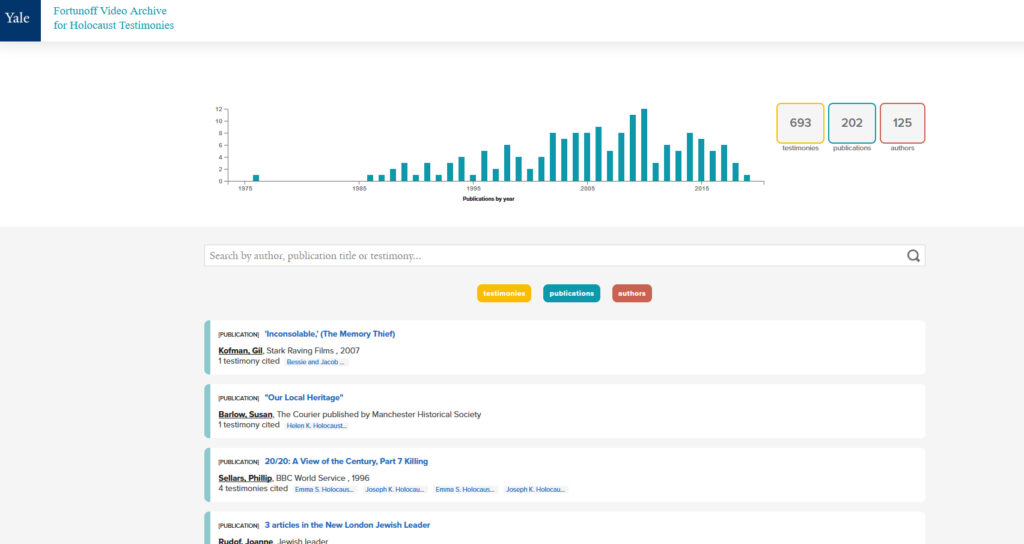

The metadata of responsa – when they were written, to whom, by whom, from where, and to where they were sent – can be digitally quantified and visualized in different ways. HaMapah examines the effects of national and cultural borders on the spread of rabbinic authority. Data visualization shows the ‘reach’ of Rabbis who lived near one another, either at the same time or in succession, demonstrating rabbis’ authority.

For example, while mapping Noda Bi-Yehuda, a two volume responsa work by Rabbi Yechezkel ben Yehuda HaLevi Landau (1713-1793) who was an influential authority in halakha (Jewish law), the researchers discovered significant differences between the two volumes, as they represent distinct parts of his career.

The responsa in volume 1, published in 1776, are scattered across a wider geographic area than those in volume 2 (published posthumously in 1810), even though it contains only about half the number of responsa and was composed earlier. Those in volume 2 are much more densely concentrated in Bohemia, Moravia, and Hungary, whereas Volume 1 includes more responsa to Germany and Poland. It seems that the publisher, who was actually Landau’s son, wanted the contents of the book to shape and perhaps geographically expand his father’s reputation. The knowledge gained through visualization leads Fischer to assert that “the implication is that Rabbi Landau had a certain geographic consciousness. He was aware that a greater reach implied greater halakhic authority and had a mental map of his sphere of influence, or at least of the sphere of influence he wished to project to his readers.”[2]

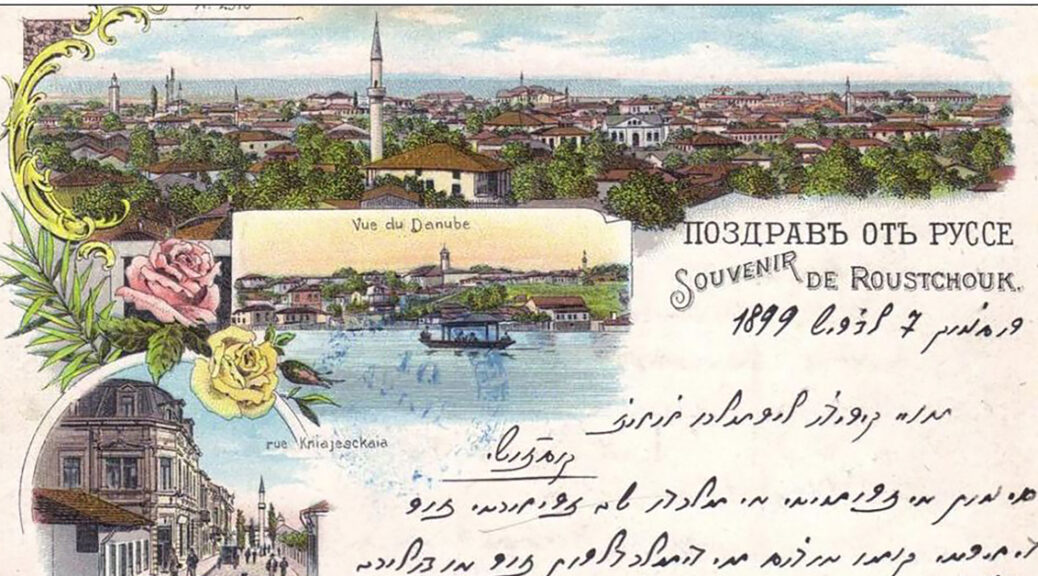

The success of HaMapah has branched out to adjacent projects, including a Searchable Map of Hebrew Place Names, and the comprehensive database of Prenumeranten. Similar to today’s crowdfunding campaigns, the Prenumeranten were lists of readers who presubscribed to books before publication. Those lists were printed in around 1700 Hebrew books published during the 18th-20th centuries. They document almost 10,000 distinct places of Jewish residence, mainly in Europe, as well as the names of hundreds of thousands of individuals. Each subscription – noting a specific person, living in a specific place, buying a specific book in a specific year – is a data point in a vast network of cultural interactions. For example, Fischer used this vast data set to reconstruct the itineraries of three booksellers as they sold subscriptions throughout Europe in the mid-19th century. He also researched the reception of specific authors and their works in various communities, such as that of Rabbi Eliyahu of Vilna (1720-1797), better known as the Vilna Gaon.

The HaMapah and Prenumeranten projects effectively combine historical documents and cutting-edge technologies to shed new light on the intersections of travel, book culture, and Jewish history. While these projects are still in their infancy, I encourage readers to visit the website for conference papers on their early findings and to learn more about these important projects.

Additional reading:

Fischer, Elli and Schorr, Moshe. Analysis of Metadata in Responsa : Methods and Findings. Innovations in Digital Jewish Heritage Studies – the 1st International Haifa Conference. July 13, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MV9N1Zt15Uc (video).

Haas, Peter. Responsa : literary history of a rabbinic genre : Atlanta, Ga. : Scholars Press. 1996.

https://openlibrary-org.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/books/OL8151172M/Responsa

Freehof, Solomon Bennett. The responsa literature : Philadelphia, Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955. https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/9e1640/alma991031462519706011

Flatto, Sharon. The kabbalistic culture of eighteenth-century Prague : Ezekiel Landau (the ‘Noda Biyehudah’) and his contemporaries : Oxford, UK ; Portland, Or. : Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2010. https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/9e1640/alma991035983629706011

Fischer, Elli and Ganzel, Tova. A Glimpse of Rabbi David Zvi Hoffmann’s Methods as a Decisor of Halakhah (Hebrew). JSIJ – Jewish Studies, an Internet Journal.

https://jewish-faculty.biu.ac.il/sites/jewish-faculty/files/shared/JSIJ22/ganzel_fischer.pdf

Fischer, Elli. The Prenumeranten Project: Digitizing Pre-Subscriber Lists. Digital Forum Showcases, European Association of Jewish Studies. January 21, 2022. https://www.eurojewishstudies.org/digital-forum-showcase-reports/the-prenumeranten-project-digitizing-pre-subscriber-lists/

[1] Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire spectrum of rabbinic writings throughout Jewish history. However, the term often refers specifically to literature from the Talmudic era, as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic writing. In academic research, Rabbinic literature includes the Mishnah, Halakha, Tosefta, Talmud, Midrash, and related writings (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbinic_literature).