Annah Hackett is the Information Literacy Librarian for the University of Texas Libraries.

In Undergraduate Studies (UGS) library instruction sessions, the librarians of Teaching and Learning Services (TLS) work with undergraduate students on the research skills they will need to succeed at the University of Texas. Of particular note are discussions about source analysis: Is this the type of source I need? Is it credible? How can I place it in context within my thesis? Most of this instruction is classroom-specific, but TLS always seeks to tie these skills to the broader context of the information students will encounter in the “real world.”

So when Alanna Bitzel – Texas Athletics Student Services Assistant Director for Supplemental Instruction, Writing and Academic Enrichment – asked if I would be interested in leading an information literacy session as part of the new Summer Writing Bridge Program, I saw a unique opportunity to demonstrate how information literacy skills can benefit student-athletes both in- and outside the classroom.

Under Bitzel’s leadership, the Summer Writing Bridge Program provides an opportunity for student-athletes to connect with academic resources on campus, including the Libraries, tutoring services, and the Writing Center. The purpose of this program – now in its first summer – is to empower student-athletes to utilize these resources as they balance their challenging course schedule and athletic responsibilities.

Bitzel sees one of the major concerns student-athletes will encounter is how to navigate endorsement deals. Since 2021, NCAA student-athletes have been permitted to enter contracts with companies who seek to use their name, image, and likeness (NIL) to endorse their products. This is an exciting opportunity for students to make money and connections while they are still in college. However, this opportunity also comes with potential pitfalls. Specifically, students might be so excited to be offered a paycheck that they contract with companies whose values don’t align with their own. To avoid this, student-athletes need to research and analyze the companies who are offering them an endorsement deal. In other words, they need information literacy skills.

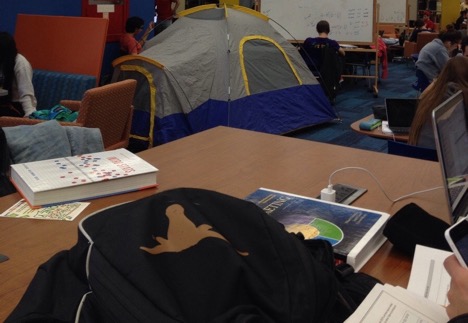

Nine of the students enrolled in the Summer Bridge Writing Program came to the Perry-Castañeda Library (PCL) recently to work with a representative of the Writing Center and myself. For some of the attendees, this was their first visit to PCL. I started off by inviting the students to partake in something that I consider an essential tool in critical thinking: homemade cookies. Once they had filled their plates, I then asked them to consider a fictional situation. What would they do if a company selling vitamins and supplements to athletes sought to contract with them for their NIL in their next media campaign? Specifically, what information would they want to know about the company, and where they would find that information?

In a lively group discussion, we worked our way through researching other “brand ambassadors” for the company, checking for FDA approval, seeing if there have been any major scandals concerning the company in the media, and reading the “About Us” page on the company website. I then told the students that their research had revealed that the head athletic trainer at another university had endorsed this company in the past. In my fictional scenario, this person was professionally successful but did not have an educational background that enabled them to say whether a vitamin or supplement would help or harm a person. This led to a conversation about professional and educational expertise.

Eventually, the students agreed that they would not accept this endorsement. For one thing, I had forgotten that athletes using supplements is problematic, if not strictly against the rules. That librarian error aside, the students agreed that the lack of FDA approval (professional standards) and the fact that the other brand ambassador did not have a medical background (educational expertise) made this endorsement too risky to accept. One student-athlete said that she would also ask the head athletic trainer at UT what they thought about the company, which is another way of seeking information from experts in the field.

Having agreed that we would look elsewhere for our endorsement deals, we rounded off the session by looking an actual research assignment from a UGS class. We discussed how they would use the same skills and analysis from the NIL prompt to research the topic given to them by this UGS professor: determine what expertise in this particular situation looks like, use critical thinking skills to figure out what types of sources they needed, and analyze the sources for credibility. Information literacy skills are essential for success both inside and outside the classroom!

The session with the Summer Writing Bridge Program was a fun way to connect with a group of students outside of how I usually interact with them in a UGS classroom. It also gave me an opportunity to show students how information literacy works “in the wild”.

While we spend most of our time supporting undergraduates through their classroom assignments and projects, it is always important to remind them that the skills they learn here at UT can guide them throughout their lives and that librarians are here to help them learn what questions to ask, with or without cookies to make the process more fun.