What is the Black experience in the Americas?

It’s a question that has not gotten due consideration, and one that helped to initiate the development of an archive focused on collecting and preserving resources that hold the history and experience of the African migration to the Americas.

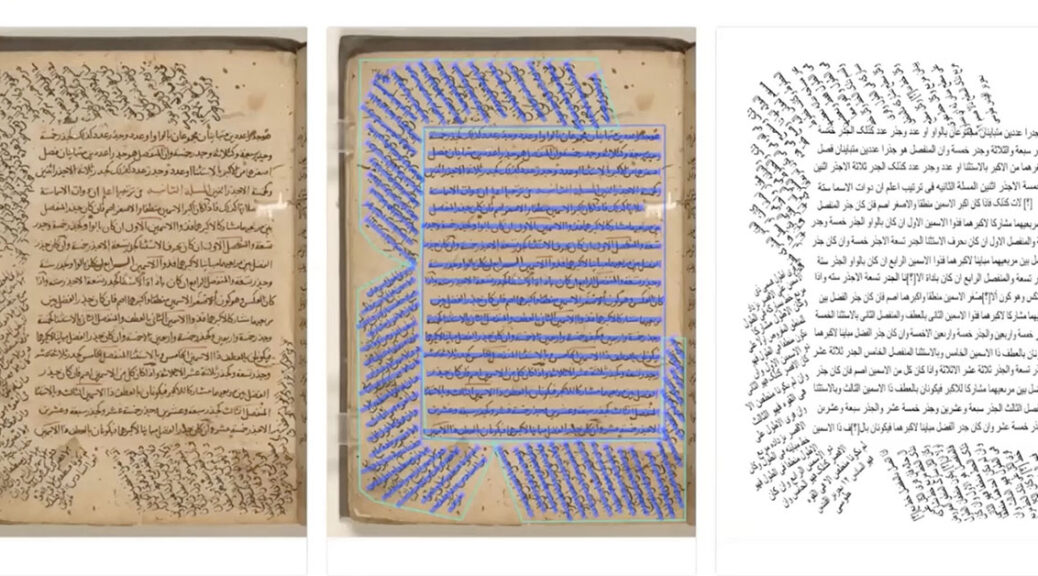

A collaborative project between Black Studies, LLILAS Benson and the University of Texas Libraries, the Black Diaspora Archive (BDA) was conceptualized in 2013 to collect documentary, audiovisual, digital and artistic works related to the Black Diaspora of the Americas and Caribbean, focusing on people and communities with a shared ancestral connection to Africa. The archive encompasses historical publications, contemporary records, personal papers and rare material produced by and/or about people of African descent — including scholars, professionals, community groups, activists and artists.

While the geographic collecting area for the Black Diaspora is global, this collection is currently focused on materials documenting experiences from within the Americas and the Caribbean. Recognizing the broad potential in a partnership, Black Studies approached LLILAS Benson with the idea of creating an archive devoted to resources related to the Black Diaspora. Since its founding in 1921, the Benson Latin American Collection has actively collected Latin American materials that document communities and people of color, but it had never done so in a deliberate way. Principals in each unit recognized the common objectives and shared vision between them, and the mutual benefit of developing a dedicated archival holding of material related to the Black Diaspora. With additional support from the Libraries and the Office of the President, the Black Diaspora Archive came into being, and in the fall of 2015, Rachel Winston was named as its inaugural Black Diaspora archivist.

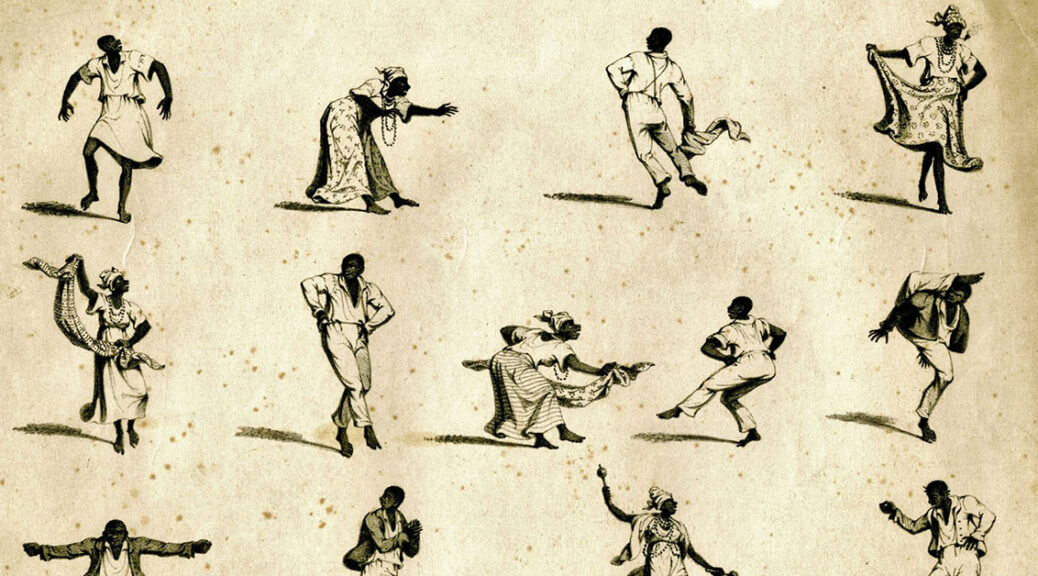

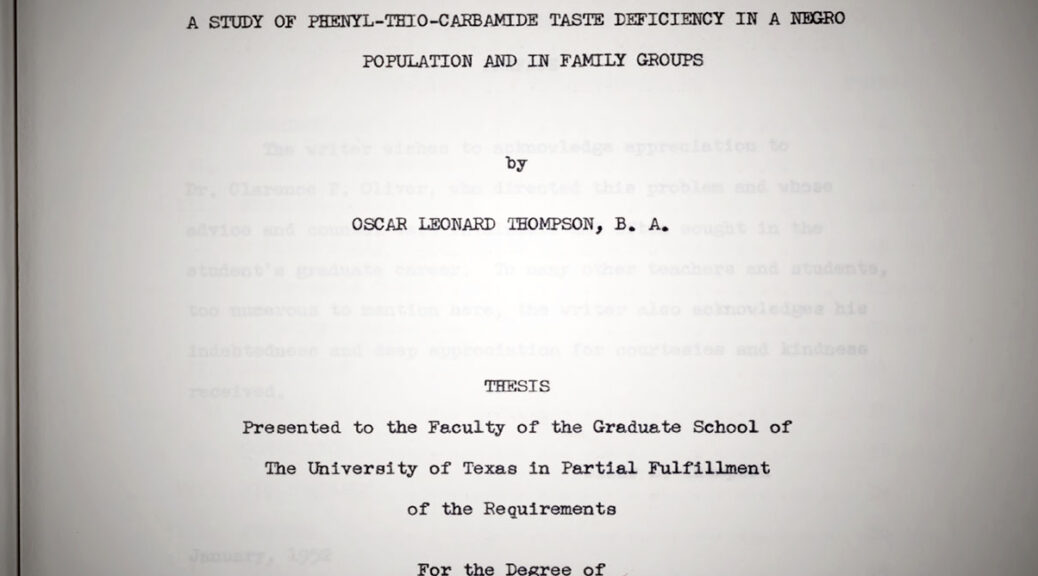

Thematically, the collection seeks to reflect art and art scholarship of the Black Diaspora, slavery in the Americas, ethnoracial empowerment and advocacy, and the personal archives of scholars and thought leaders. These types of records can include historical works, prints, digital and born-digital content, and other rare material.

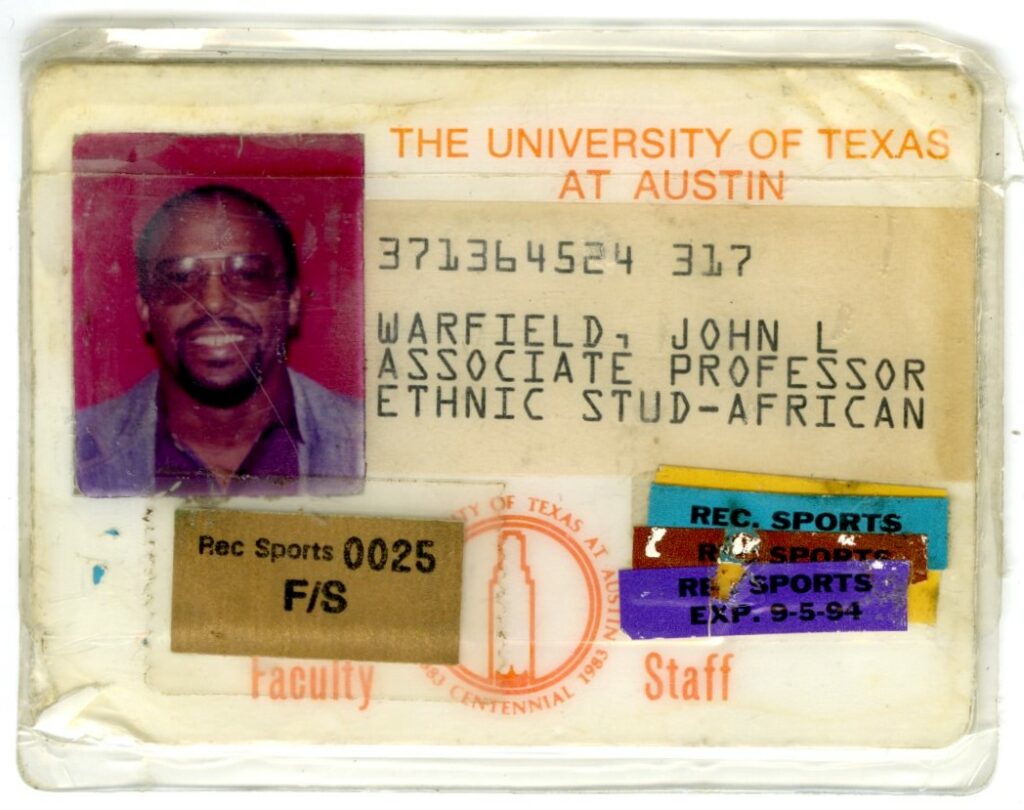

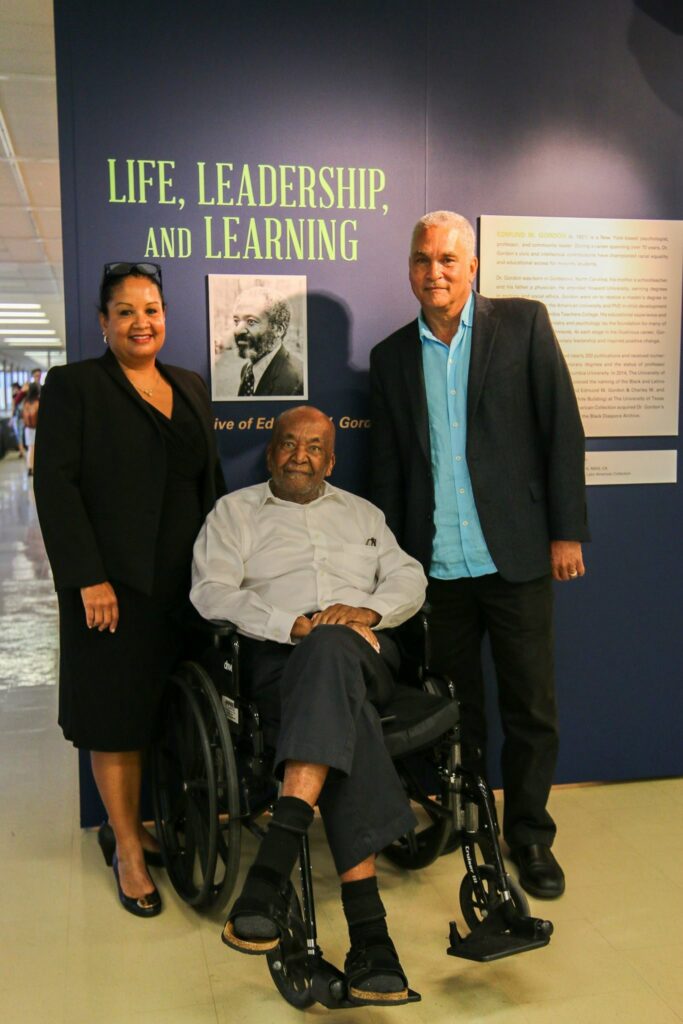

Although the scope of the BDA’s acquisitions strategy can be categorized neatly into these simplified groupings, a brief overview of some of the resources included in the collections underscores how much is needed to be done in preserving and studying the Black experience and its historical impact on our culture and society. From documents on the slave trade in the Black Diaspora in New Spain, to oral history collections like that of the Shankleville freedom colony in East Texas, to the papers of influential Black intellectuals and activists like Edmund T. Gordon, John L. Warfield and Brenda Burt, to collections of art and art history, the BDA has just begun to scratch the surface in preserving and making accessible resources for beginning to examine the role of the Black Diaspora and Black scholarship in the Americas.

In addition to collecting, the BDA works to promote collection use and research through scholarly resources, exhibitions, community outreach, student programs and public engagement.

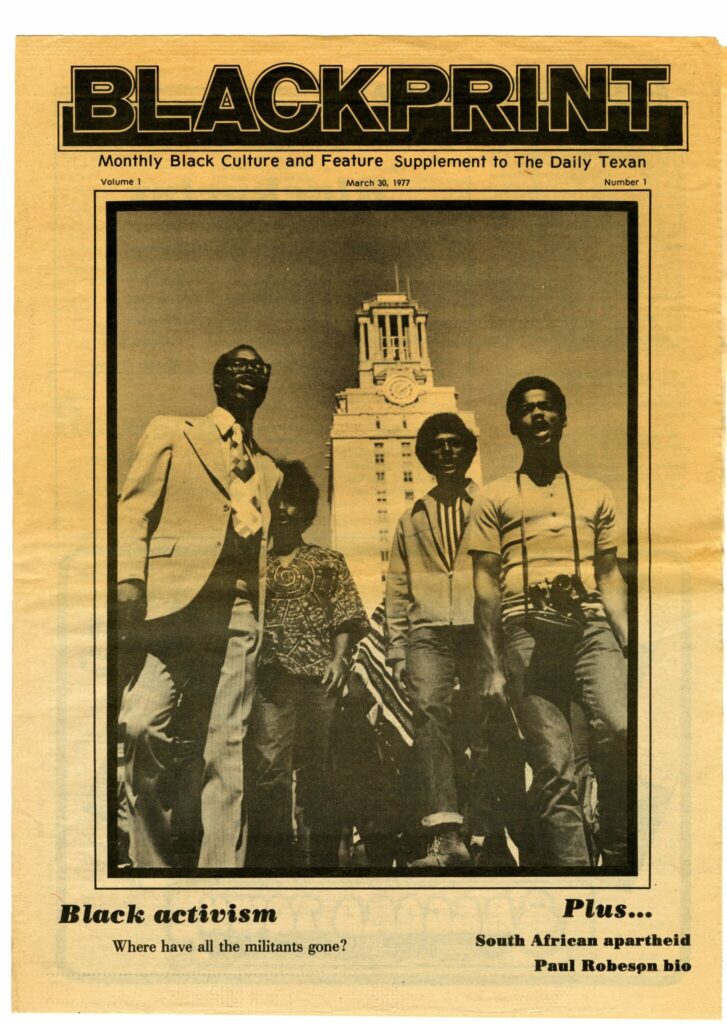

Black print newspaper (1977). John L. Warfield papers.

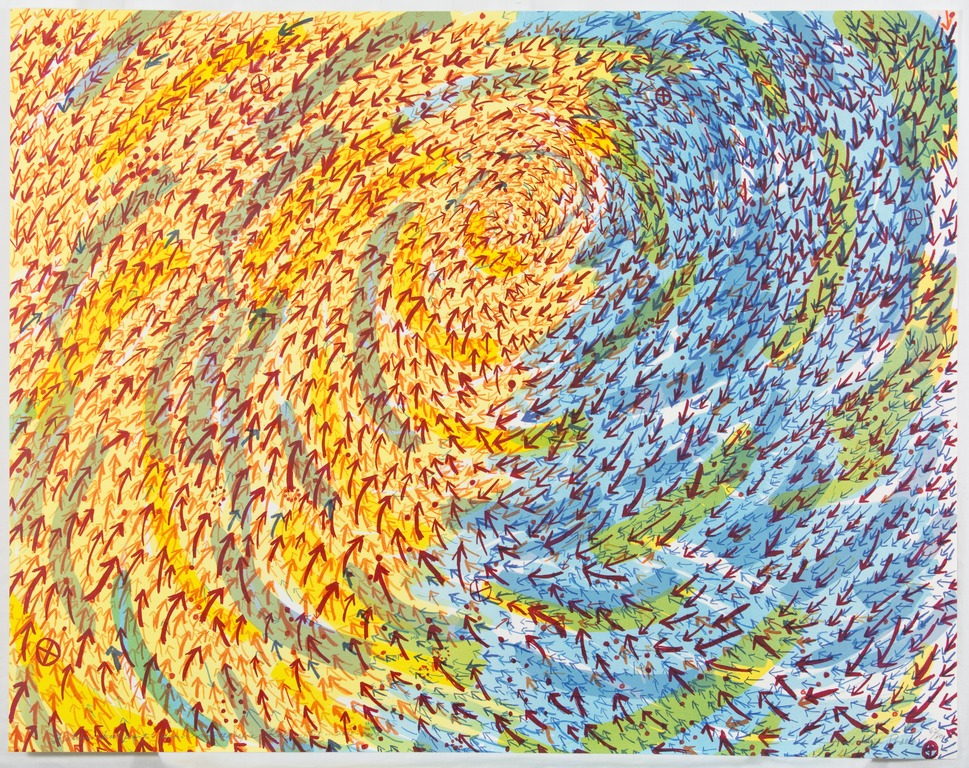

“Katrina” by Howardena Pindell, 2005. From Surrounded by Space. Photo by Mark Doroba, The Visual Resources Collection, The University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

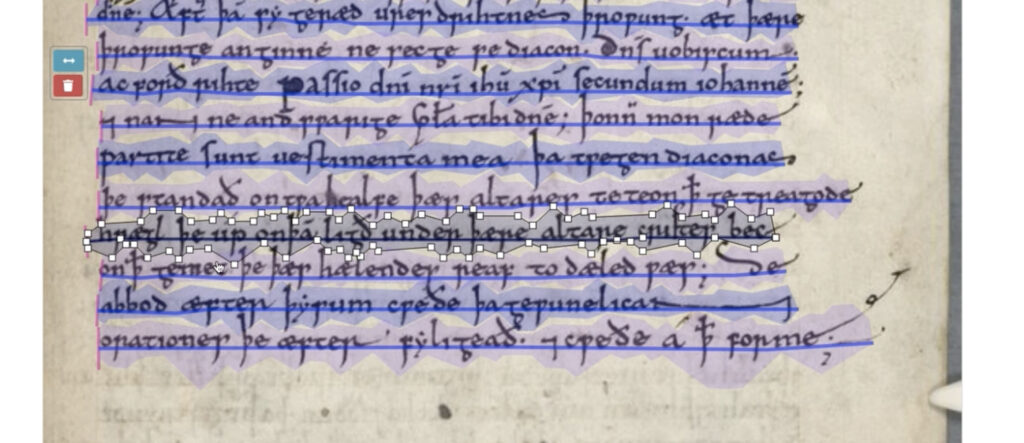

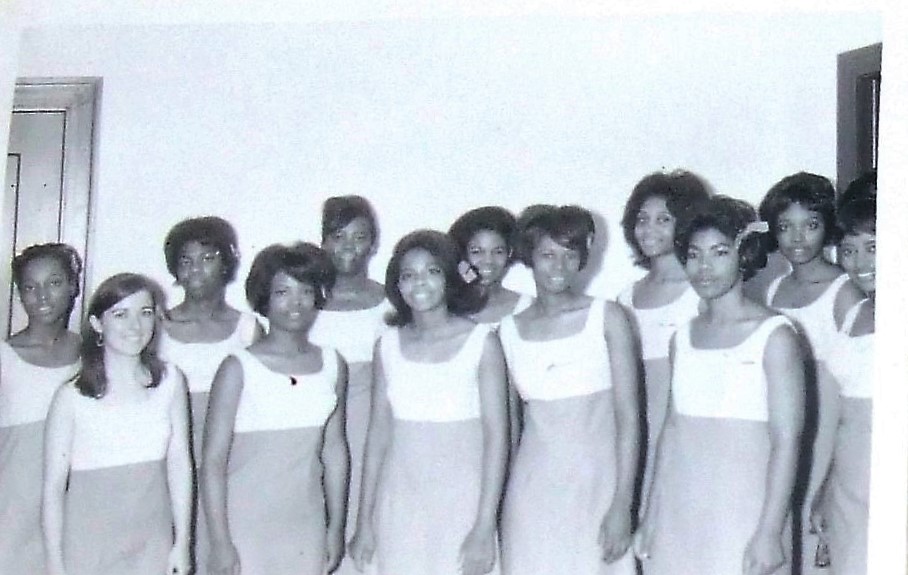

Delta Xi of Spring 1966: Camilla Jackson, Beverly Robinson, Karen Williams, Pamiel Johnson-Gaskin, Carolyn Cole, Ruth Franklin, Mary Gordon, Linda Lewis, Mary Poston, Shirley Tennyson, Barbara Ward, Debbera Williams.

Photo courtesy of Pamiel Johnson–Gaskin.

John L. Warfield Faculty ID card (1994)

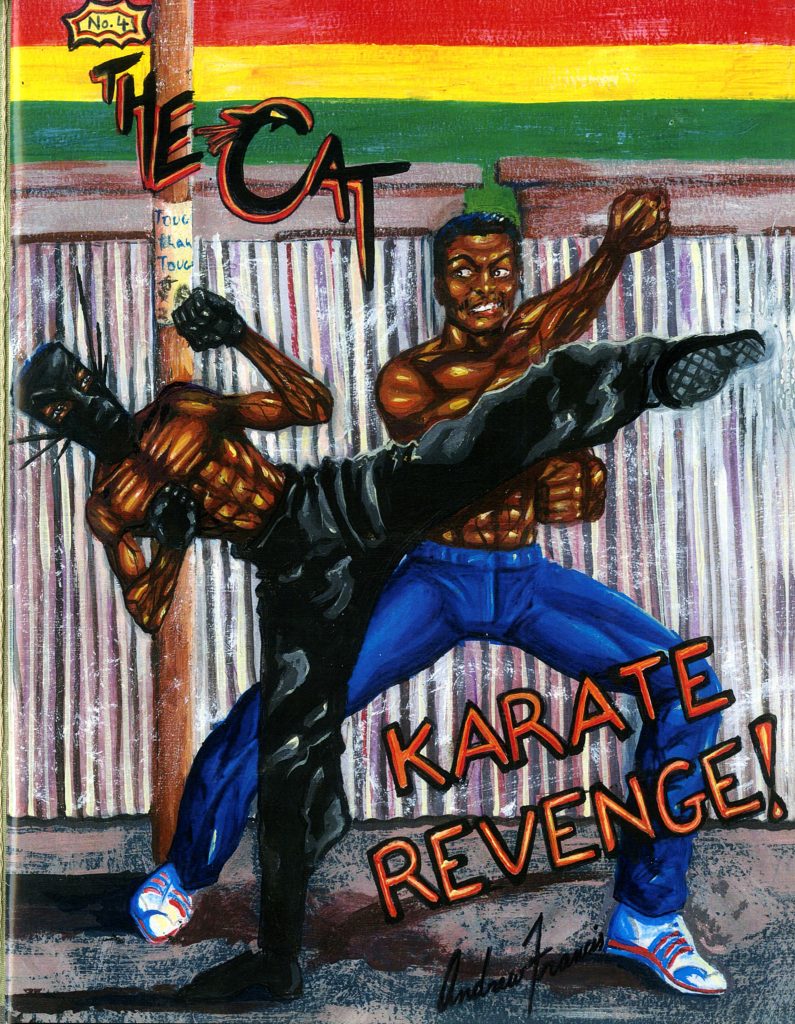

“The Cat, Vol. 4” by Jamaican graphic novelist Andrew Francis.

Edmund T. Gordon and family members at the opening of his archive.

“As the primary manager of the Black Diaspora Archive, my ultimate charge is to provide a fuller understanding of the Black experience throughout the Americas and Caribbean with primary sources,” says Winston. “In the most traditional sense, this necessitates the acquisition, collection, preservation, and accessibility of archival records.”

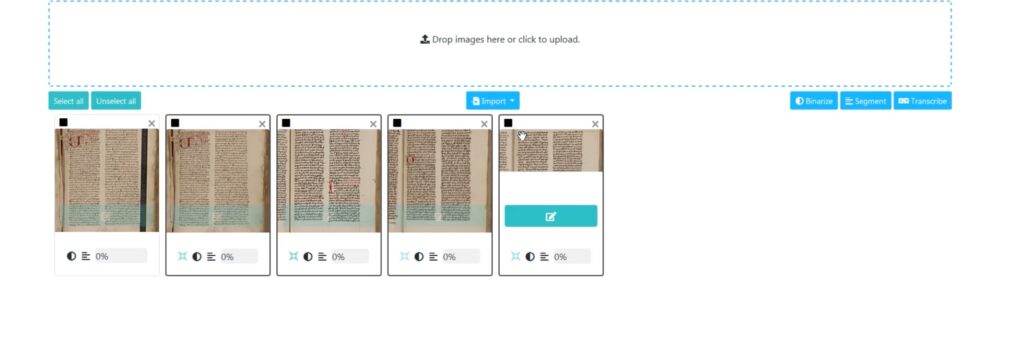

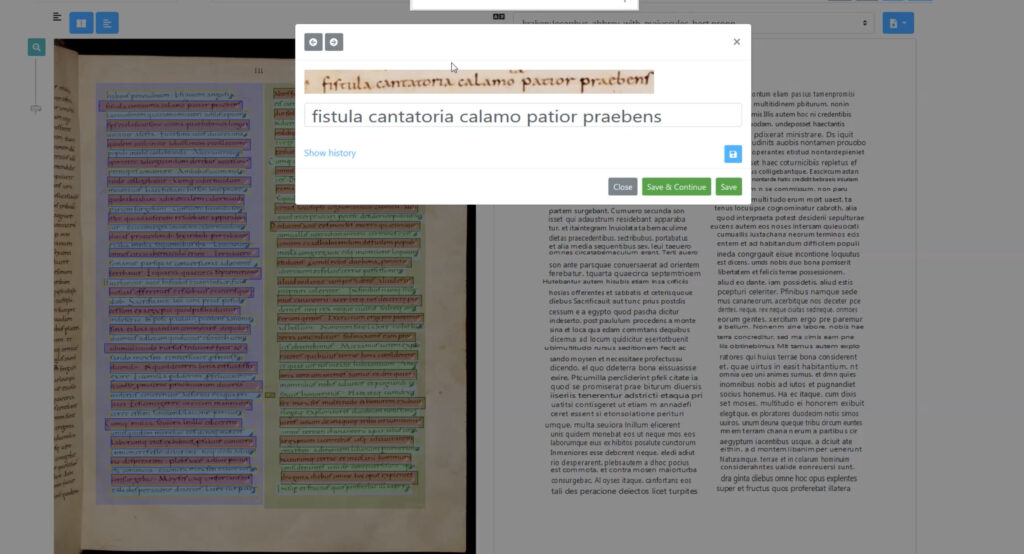

“However, as our communities become more connected and technologically advanced, information access and information needs continue to evolve in ways that are increasingly less traditional,” continues Winston. “User needs of today, for example, live largely in the digital realm. In facilitating access to online content, the archivist has more of a responsibility to perform outreach and promote information literacy skills in an effort to preserve the integrity of our collections and meet user needs.”

“I am so excited for what we have been able to achieve so far and just the general sense of support on campus for this project that I am confident we will move forward, in order to move forward and achieve what’s possible, we need all of this outside support we can get.”