Hard to believe it’s been two years since the sudden closure of these Libraries upended our work and forced us to rethink how we continue to operate in a world that has the potential to throw such wild curveballs. A lot of the work we did before will likely return much as it was before we left the Forty Acres and adjusted to the boxed in screen of video interactions that would become the workspace for much of our library work for an extended period.

But much of the change required to keep the Libraries running through the remote period and into the initial reopening of spaces and return to in-person activity will remain in place as we enter the next normal. The paradigm of normal has shifted irrevocably thanks to a health crisis that has cost over 5 million lives, upended social practices and impacted the way we behave in so many ways, positive and negative. There was a normal before we knew of COVID-19, and there is a different normal as we proceed. To address that next normal, there are changes that won’t disappear, even when the pandemic eventually does.

So, what are the sustainable, smart changes that the Libraries will continue going forward?

Accessibility to Online Resources. The primacy of digital access was clear immediately upon the arrival of COVID. Without a robust online presence, academic enterprise and research innovation would have been greatly hindered, but through quick negotiation affected by a shared interest in continuity with providers, staff were able to ensure the best possible resources were available through emergency accommodations by the publishers, and favorable decisions about access to resources in HathiTrust. That experience provides a blueprint for continued access to resources and can inform future negotiations with publishers and content partners.

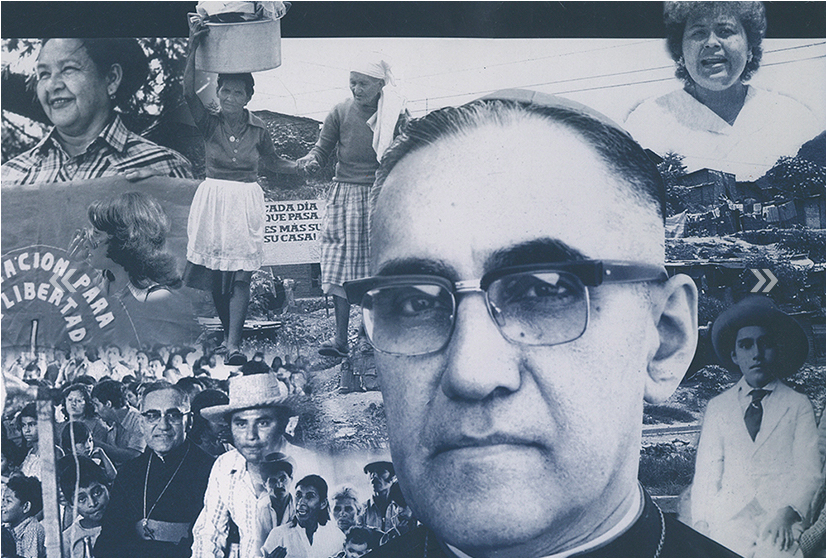

IDEA and Collections. One byproduct of the crisis was our captivity to a constant stream of news, and the effect of social upheaval on our strategic practices. The racial reckoning provided an opportunity to reflect on collections strategy and recalibrate our orientation. A project to diversify the collections is already well underway and will be a permanent part of our thinking going forward. And new digital applications like Spotlight will allow for the curation and highlighting of materials that reflect the breadth and diversity of our user community’s interests.

“Our time away from campus was not limited to the suffering brought on by the pandemic,” explains Head of Information Literacy Services Elise Nacca. “The murder of George Floyd prompted vital conversations on our campus, including interrogating whose story gets told at this University and what responsibility do we have to seek out diverse viewpoints? Critical pedagogy asks us to interrogate how power shapes the creation of and access to information. I worked to address in my classroom the gaps and silences in scholarship and how students can use our resources at the Libraries to seek out perspectives missing from the conversation.”

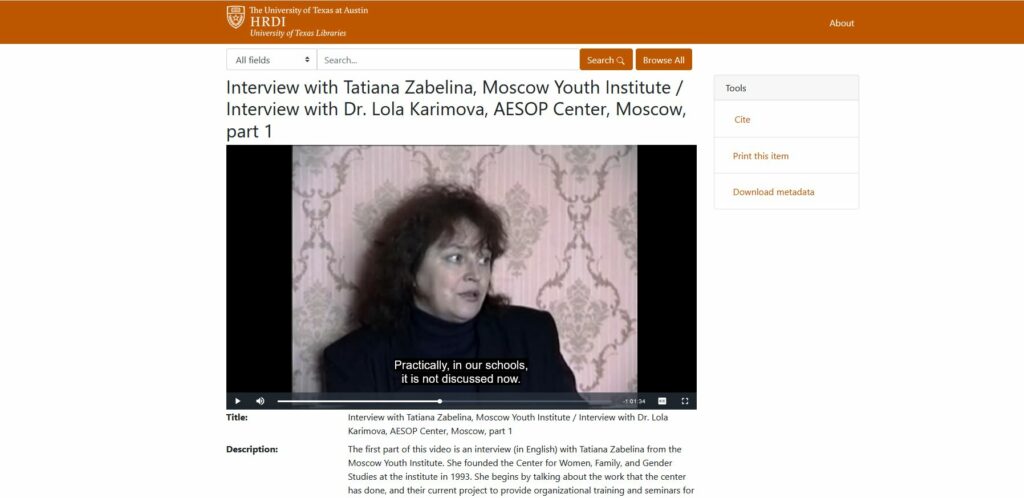

Promoting Legacy Content. The launch of the Libraries’ Digital Asset Management System (DAMS) in 2019 couldn’t have been more fortuitous, providing a framework and processes for sharing extant digital content with a community that was abruptly cut off from physical access to primary resources. Innovative thinking aligned with open access principles to realize opportunities for leveraging the DAMS for collaborative work. One such example is work on the David Reichard Williams Collection at the Alexander Architectural Archive, where staff enlisted a larger group of formal and citizen scholars to build out metadata for the collection through a crowdsourcing effort. This novel approach can be applied with equal effect even during a period that doesn’t require distance between contributors.

“We made a big push to provide more digital access to library resources,” explains Sean O’Bryan, Assistant Director of Access. “Along with exponentially increasing identification, description and ingest of content into the DAMS, we also took advantage of HathiTrust Emergency Temporary Access Service (ETAS) making these digital surrogates easily discoverable in Primo (the Libraries’ content discovery system). This immediate benefit of providing a ‘virtual library’ during the pandemic has informed our exploration of controlled digital lending in order to advance that potential post-pandemic.”

The Dawn of the Virtual Session. Perhaps one of the most important evolutions of the pandemic was the development of collaborative meeting platforms like Zoom and Teams, allowing the adaptation of in-person services and expertise in a virtual environment. Research consultations, workshops and meetings all migrated to these platforms out of necessity during the pandemic, and now they have become a regular, and likely permanent fixture in how we interface with our constituents.

“One of the biggest changes made after the start of the pandemic was a switch from exclusively in-person workshops to completely virtual Zoom webinar-based workshops,” says Geospatial Data Coordinator Michael Shensky. “It wasn’t initially clear whether patrons would show up in the same numbers we had come to expect for in-person workshops, but we found that attendance for virtual workshops was actually significantly higher than for in-person workshops on similar topics that were organized during semesters prior to the pandemic.”

Having access to expert librarians for reference support is a core function at academic research institutions, and so the sudden impact of closures on research consultations – a service that was mostly an in-person exercise – could have been detrimental. Once again, Zoom provided a ready solution for an unexpected challenge. “It’s a great format for this type of work and allows people to meet with us from wherever they are,” says Jenifer Flaxbart, Assistant Director of Research Support and Digital Initiatives.

“Zoom was a godsend, for many reasons, and it’s now a staple in all facets of our work,” continues Flaxbart. “These virtual learning tools and platforms can be used both synchronously and asynchronously, and they permit global-level engagement, 24/7.”

Collaborating in the Digital Space. Teaching and learning online is not so easy to navigate successfully, and not every tool is equal, but what did work was using online whiteboards such as Padlet and Google Jam Boards during instruction sessions. These tools allow students to post ideas and responses quickly and teachers can see the posts in real time to facilitate discussion. Students can see what their colleagues are posting as well, and can participate anonymously. These tools will continue to find a space as in-person teaching and learning continues to ramp up with the gradual return to campus.

Where’s the Community? One of the greatest losses of the departure from campus at the arrival of the pandemic was the bustle and din of activity in Libraries’ spaces. When students returned in a limited capacity, the hesitancy created by risk factors made for a slow return to formerly beloved student congregation areas. Amplifying the challenge of providing a communal and collaborative workspace is the disparate experience of latter career students and those whose academic life began in a remote environment. Navigating the adapted needs of users in the physical space is a hard road of work ahead, but with the earnest return to campus, we’re seeing increasing traffic in spaces, and an expansion of in-person services, though not at pre-pandemic levels, yet.

“Teaching first year students, you’re always aware of the challenges someone coming to our campus for the first time might face,” says Elise Nacca. “It’s big and overwhelming and it’s easy to get lost physically and mentally. Before the pandemic sent us all home, I don’t think I appreciated how much most students really love being on campus and how much many lost staying home. I saw a lot of sad faces in Zoom classrooms and a lot of silent black boxes staring back at me. I wondered more than ever how they were feeling.”

“This led us to include more inclusive teaching practices into our work. This could be something simple like using inclusive language and examples in search demos to more intensive work, such as providing multiple formats for engagement with course materials,” explains Nacca. “I included more videos and screenshots of my content because I felt like I could not check in with students as easily as I could in person in order to check if they understood a concept. A stressed-out student on a lousy internet connection could follow images of searches or watch a video on their phone if the Zoom session wasn’t easy to engage with.”

“Overall, Covid has pushed our users to embrace the ‘Platform’ even more,” says Jenifer Flaxbart. “It’s key that our staffing and services align with that and do not overemphasize Library-as-Place and in-person work needlessly, particularly with faculty and graduate students, who’ve shown they prefer remote work and virtual collaborations with librarians and related Libraries’ experts.”

Working Differently. There’s no question that the experience of almost two years in a pandemic that has separated people from a professional structure and shared space can stymie efficiencies that have been built for existing practices and processes, so in adjusting workflows to a radically different work environment, staff chanced certain operational discoveries that might’ve otherwise not been considered.

The Digital Stewardship staff took on a lot of additional work to help units across the Libraries provide access to materials that were no longer available in physical form, including support in scanning materials for ILS (interlibrary loan) requests. That workflow could have sunsetted as ILS staff came back onsite, but the experience opened the door to the idea of scanning materials for different kinds of workflows. “Now we are scanning materials for the Controlled Digital Lending pilot,” says Assistant Director of Stewardship Wendy Martin, “and will build out those workflows as needed if that becomes a service.”

Transitional projects, which are mostly one-time affairs, gained some added benefit from the peace of campus closure. The pandemic allowed Stewardship staff to approach a project to vacate Battle Hall for a renovation project (as well as some other collection moves) in a more deliberate way than might have otherwise been possible. “The Storage and Logistics team and Architecture team and Preservation team were able to work onsite while the Architecture Library was closed for the pandemic, instead of having to fit the move into an intersession period,” says Martin. “The library was closed, but staff could work onsite preparing materials, and remain socially-distant from each other as they carried out the work. Having that time and space to move that collection out of Battle was beneficial for the move out, and also informs how we will move it all back in.”

Mindset and Headspace. There’s no question that the experiences of the past two years have affected attitudes and orientation about work/life balance. So in addition to the outward facing changes that directly impact our users, there have been efforts to take into consideration the challenges and varying experiences of Libraries’ staff. There’s a real concern that with a slew of changes like those mentioned here, burnout and exhaustion can loom behind the satisfaction of surviving such an unexpected series of challenges. Units within the Libraries are recognizing a role in making sure that the Libraries’ are taking care of its own, as well as its users.

“While new approaches to our work have been exciting and productive, they are simultaneously overwhelming,” says Jenifer Flaxbart. “Managerially, the Research Support & Digital Initiatives Engagement Team focused on communication, reassurance and ‘grace’ in acknowledging that the many stresses and moving parts and unpredictable, ever-changing conditions regarding physical, psychological and emotional health, living arrangements, family roles and obligations, financial impacts, loss and more. We aimed for those things before the pandemic and continue to give more pronounced focus to those things now.”

As these Libraries move towards certainty, we’ll bring with us lessons learned from the challenges of the last two years. Amid the experimentation – some efforts resulting in success, others not – there is one perspective that holds both in the last normal and in the next one, stated nicely by Head of Scholarly Communications Colleen Lyon:

“We are a really service-minded profession and organization. I knew we would do what we had to do to be responsive to our users’ sudden and very different access needs. And we did. I think we spend a lot of time asking what we could do better in this profession of perfectionists, but we need to celebrate our work, too.”