A new exhibition at the Benson Latin American Collection highlights the cultural production of the region’s avant-garde artists and thinkers

By Veronica Valarino

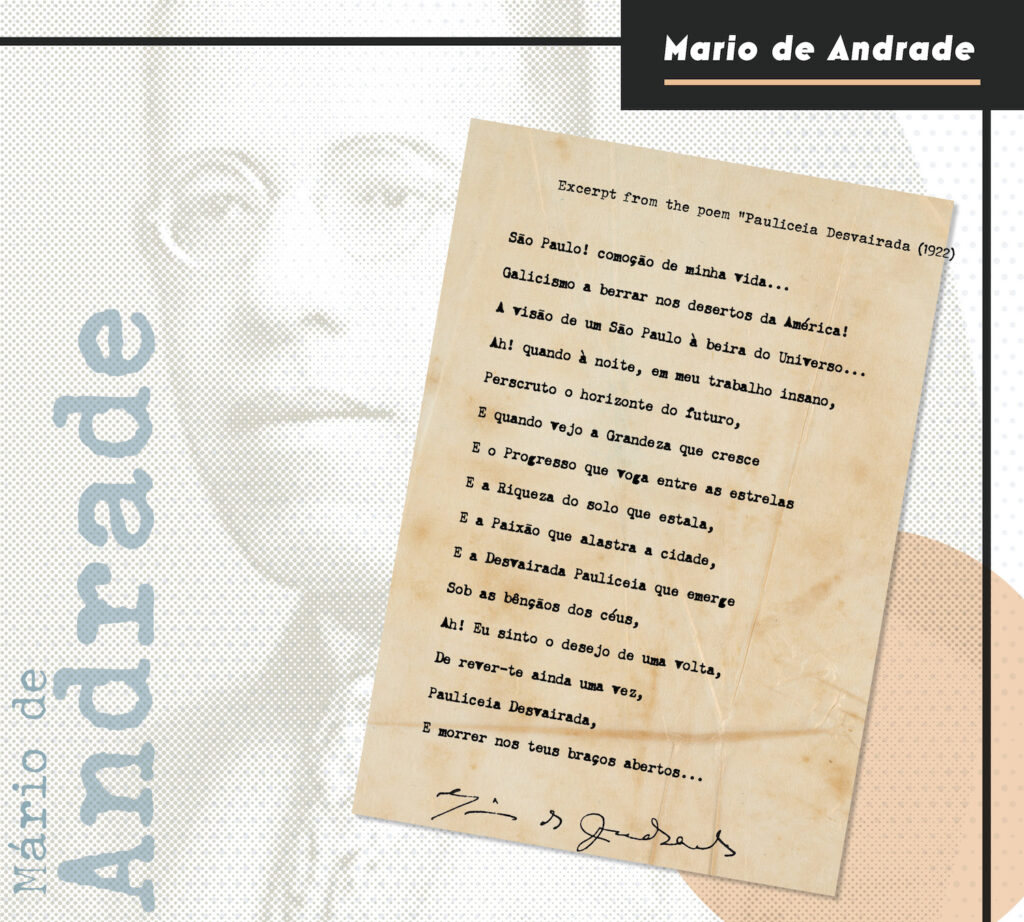

The early decades of the 20th century in major Latin American cities saw the explosion of publications and writers in a movement fueled by a growing access to publishing and an increasingly educated readership. The movement, known as vanguardismo, produced some of the region’s most celebrated writers, and reflected the dynamism and complexity of contemporary reality. These vanguardists embraced avant-garde techniques, experimental forms, and bold thematic explorations, capturing the turbulence of a rapidly changing society.

The term vanguardism originates from the military concept of the vanguard, which refers to soldiers at the forefront of a formation. In the context of the arts, avant-garde, or vanguardia, denotes innovative and provocative artistic and literary movements that emerged in Europe and the Americas during the 1920s and 1930s. These movements arose amidst a tumultuous era marked by significant events such as World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Great Depression, and the Spanish Civil War. The combination of societal dissatisfaction, technological advancements, and political upheaval prompted reflections on the contemporary crisis and an uncertain future. Avant-garde artists, or vanguardistas, distinguished themselves by their pursuit of innovation and experimentation, deliberately breaking away from established artistic traditions.

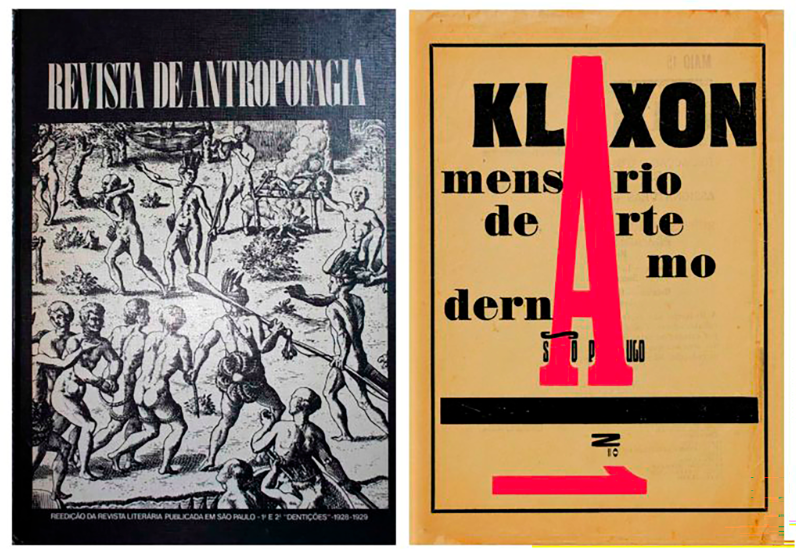

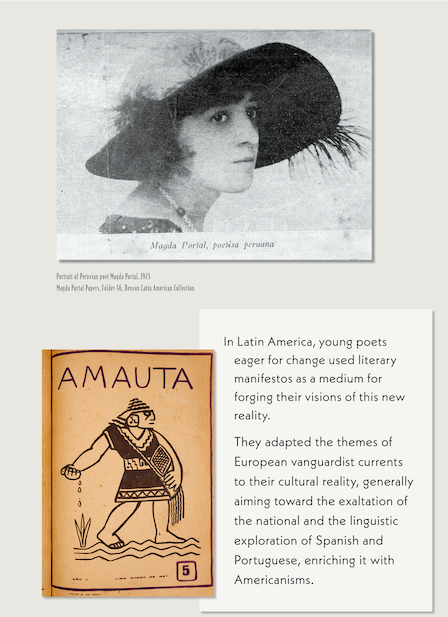

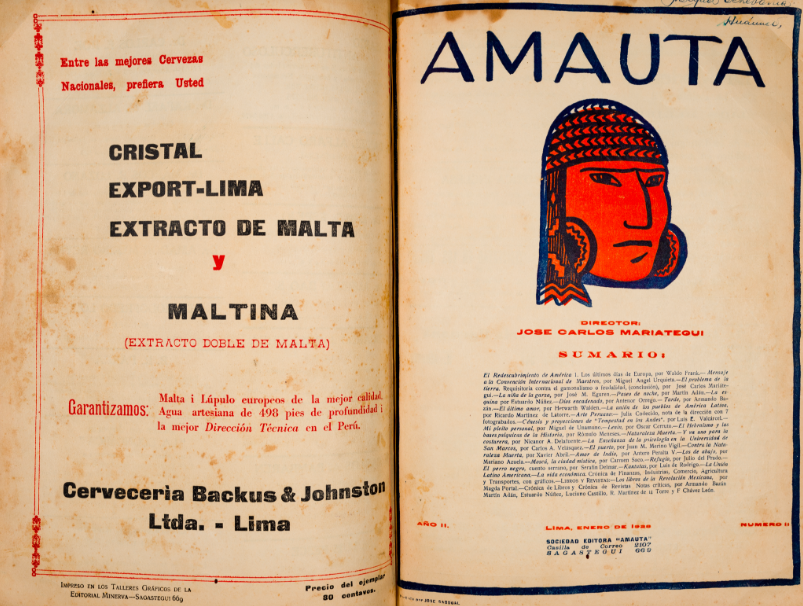

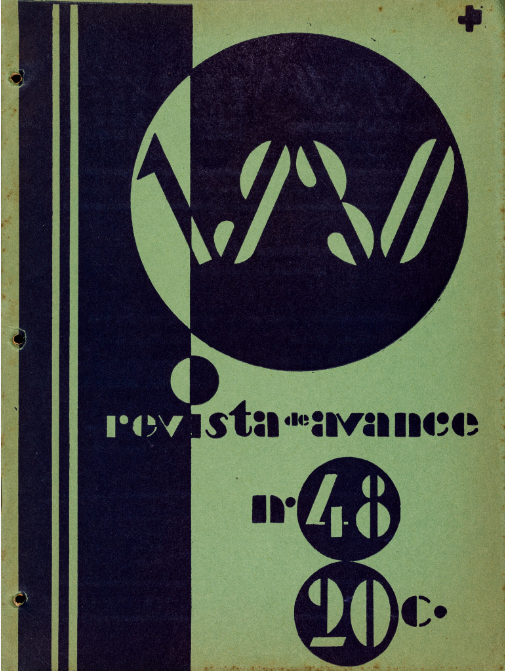

Latin American vanguardismo, characterized by its unified yet distinct cultural development, arose almost simultaneously in major cities across the region, like Havana, Lima, Mexico City, Montevideo, Santiago, São Paulo, and, especially, Buenos Aires. Vanguardists’ intellectual, artistic, and political debates were documented in numerous periodicals and magazines, which also provided a platform for vanguardist manifestos. These publications articulated expansive poetic visions, engaged in political activism, and advocated for social and political change.

Latin American vanguardismo is a significant cultural movement that gave voice to a relatively unified and distinctly Latin American art. It is also part of a larger, international movement. Hence, Latin American vanguardismo should not be seen as a mere reproduction of the European avant-garde. It was a continent-wide development, simultaneously international and autochthonous in its orientation as it grew out of and responded to the continent’s own cultural and social concerns.

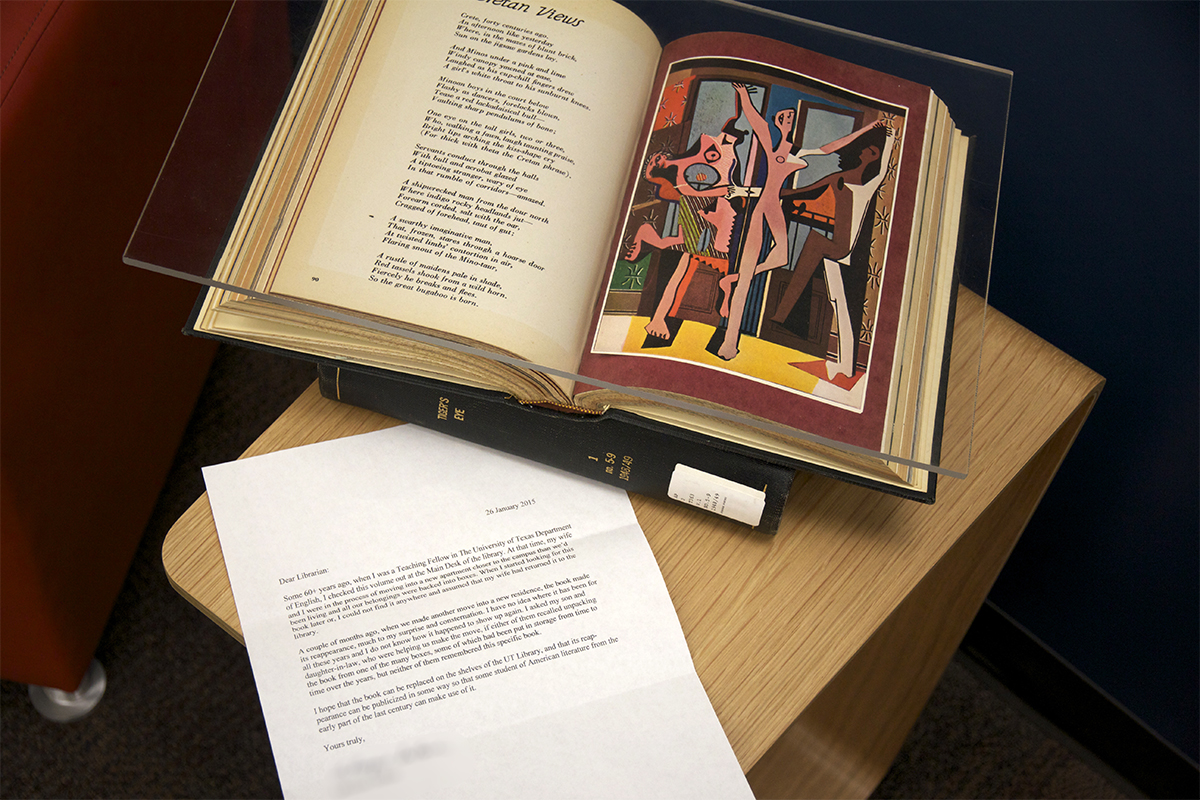

The Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection has steadily expanded its archival materials and rare books related to the cultural history of Latin America over the years. Recent additions, such as the collections of César Vallejo, Magda Portal, and Pablo Antonio Cuadra, have significantly enhanced the collection, making it an invaluable resource for research. This exhibition delves into a pivotal historical moment shaped by visionary literary luminaries. By exploring their poetic works, magazines, and manifestos, we celebrate these influential figures.

Poems, Magazines & Manifestos is on view in the Ann Hartness Reading Room at the Benson Latin American Collection (SRH 1), 2300 Red River Street, during summer and fall 2024.

Library hours: Monday–Friday, 9am–5pm. Closed July 4 and Sept. 2.

This exhibition was developed by Veronica Valarino, Benson Exhibition Curator.