Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the Libraries’ Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship to encourage and inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

The Indian subcontinent gained independence from Britain in 1947, ending centuries of colonial influence and rule, thereby creating the nation states of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh (Bangladesh was East Pakistan until 1971). Like elsewhere, the “colonial project” in India took many forms and could be readily observed through examples such as the built environment, changes in civil infrastructure, and ultimately in ways of documenting and “knowing.” Contemporaries in the colonial period noted (and in some cases celebrated) these changes in many ways too, leaving traces such as official documents and reports, personal narratives including diaries, and even ephemera. As students of history, we desperately need these primary sources to nuance our awareness of what happened in the colonial period and of how people understood the events at the time. We need documentary mnemonics. In this post, I highlight a social media project that encourages us to look closely at postcards as sources to inform our understandings of both what was considered as important (the visuals on the cards themselves) as well as how information traveled and gained collective traction (the sending and receiving of the cards, not to mention what might be written on them).

As I write this from a scenic spot in Austin on a lovely spring day, I see many folks with their cell phones out, ready to take pictures. I’m not sure why they’re feeling compelled to take the pictures—maybe to help them remember this pleasant day, maybe to document things they haven’t seen before, maybe to share with friends and family later, inviting them to imagine Austin along with them. Whatever the reason, this now ubiquitous phenomenon of quick, easy and cheap photo sharing feels simultaneously both very “natural” and very “21st century.”

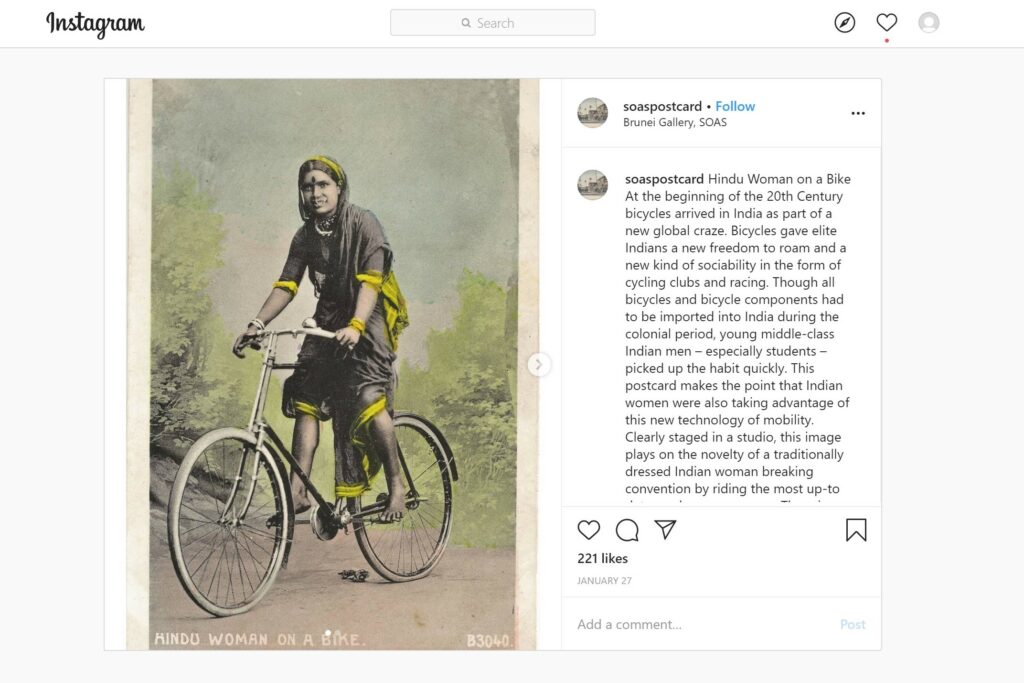

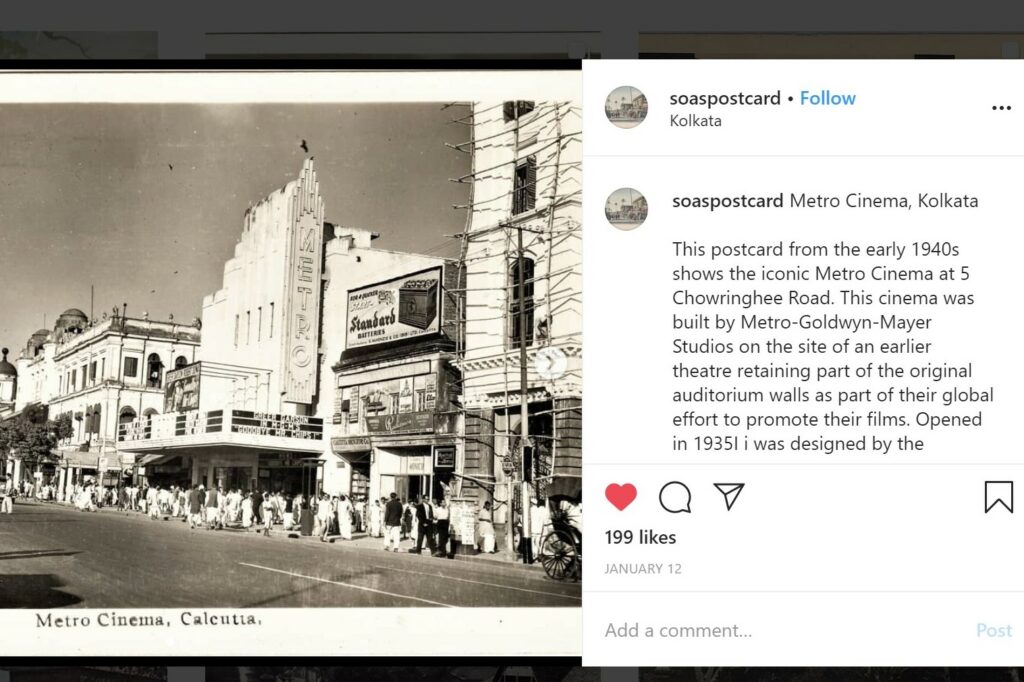

Delightful digital projects such as the “Early Postcards from India,” however, challenge my assumption that an ephemeral capturing and sharing images is a particularly “contemporary” activity. As School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) visual anthropologists Stephen Hughes and Emily Stevenson explain,

“For anyone who has lived through the recent emergence of the Internet, social media, camera phones, and digital-printing technologies, it is perhaps all too easy to assume that the rapid and large-scale circulation of photographic images is a uniquely twenty-first-century phenomenon… A growing body of literature demonstrates that since its invention, in the mid-nineteenth century, photography has always circulated, moving among different spaces, discourses, and material forms.. Of the various nineteenth-century photographic innovations, the humble picture postcard was the most widely traveled of them all.”(1)

In “Early Postcards from India,” Hughes and Stevenson build on the success of their earlier physical exhibits of postcards as historical documents. They creatively exploit Instagram’s social media platform to reintroduce and redistribute the visual memories captured in and on early postcards from India. The chosen platform is unpretentious in layout, openly accessible to anyone with an Instagram account, and constantly growing–they have a new image and related provocative or didactic post daily. Their use of Instagram, one of the most widely adopted and therefore “traveled” image innovations, to continue the circulation and consumption of these images, is a simple but highly effective stroke of genius.

The content in “Early Postcards” is wide-ranging: it includes images of monuments, of municipal infrastructures, of “anthropological types.” As such, the images evoke feelings of nostalgia, of curiosity, of unease, and perhaps, of collective regret. Thanks to Hughes and Stevenson for sharing these images so we can all collectively participate in the critiques and (re)writings of history.

Those interested in further exploring the history of postcards, of visual representation(s) and of colonial India might find these helpful starting points:

Akbar, Sohail, “An Exploration of the Early History of the Nation through Personal Photographs.” photographies 6:1 (2013): 7–15.

Jhingan, Madhukar, Post Card Catalogue of India and Native States (New Delhi: We Philatelists, 1979).

Khan, Omar, Paper Jewels: postcards from the Raj (Ahmedabad, India: Mapin Publishing, 2018).

Mathur, Saloni, India by Design : Colonial History and Cultural Display (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Nenadic, Stana, “Exhibiting India in Nineteenth-Century Scotland and the Impact on Commerce, Industry and Popular Culture” Journal of Scottish Historical Studies 34.1 (2014): 67–89.

Pinney, Christopher, Camera Indica : the Social Life of Indian Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

Ponsford, Megan, “Photographic Reportage and the Colonial Imaginary,” Sport in Society 22:1 (2019): 160–184.

Seth, Vijay, and J. R. Nanda. Centenary of Indian Airmails, 1911-2014 (New Delhi: Indian Aviation Research Foundation, 2014).

Notes:

(1) Hughes, Stephen and Emily Stevenson, “South India Addresses the World: Postcards, Circulation, and Empire” Circulation 9:2 (2019).