If there’s a single lesson to take away from this year, it’s that libraries are a lot more malleable than their long history may have given them credit for.

We’ve previously covered the Herculean effort by University of Texas Libraries’ staff to pivot from their natural in-person work environs to a distance service, then a subsequent limited return to the former, but a lot of that agility was due in no small measure to underlying efforts that were already underway when the health crisis washed over campus and the country.

Strategically, this institution has been focusing on the idea of the library as a platform: not just a storehouse for books or website of searchable journals, but an active ecosystem where resources, tools, services, spaces, expertise and community intermingle with a constantly variable presence of users to spin off scholarship and innovation back into the world. This idea factory of ever-evolving components works at its best when it creates opportunities for discovery through constant interaction of the various parts.

With the pandemic creating greater physical distance between the parts, though, it’s become essential that we focus on those tools that could best allow us to reach our users where they are, be that in an apartment in West Campus, or on the other side of the globe.

Last year, we announced the launch of a pair of systems designed to organize, preserve and create accessibility for digital iterations of physical materials that otherwise would only be available to people who could visit the Forty Acres. Our Digital Asset Management System (DAMS) was deployed in September, 2019, and in November, we published the Collections Portal on the Libraries’ website. The culmination of these two projects proved to be far more fortuitous than we could’ve imagined.

A couple months later as leadership at the Libraries was fleshing out a new strategic plan that placed special emphasis on the concept of Libraries as platform, the first case of coronavirus was discovered in the Pacific Northwest. Then, in March as the spread of the pandemic began to accelerate, The University of Texas at Austin announced first the delay of spring classes, followed quickly by a directive to move all but the most critical staff to remote work away from campus, and to shift to online learning for the remainder of the semester.

More than ever, the adaptability of the Libraries to changes in user behaviors was the institutional characteristic that needed to be positioned in response to the extraordinary situation that fell so quickly upon us all. And refocusing our collective energies on tools with the greatest potential to serve the largest number of people while considering the long-term goals of the Libraries made these new systems a natural priority for applying institutional resources.

The DAMS

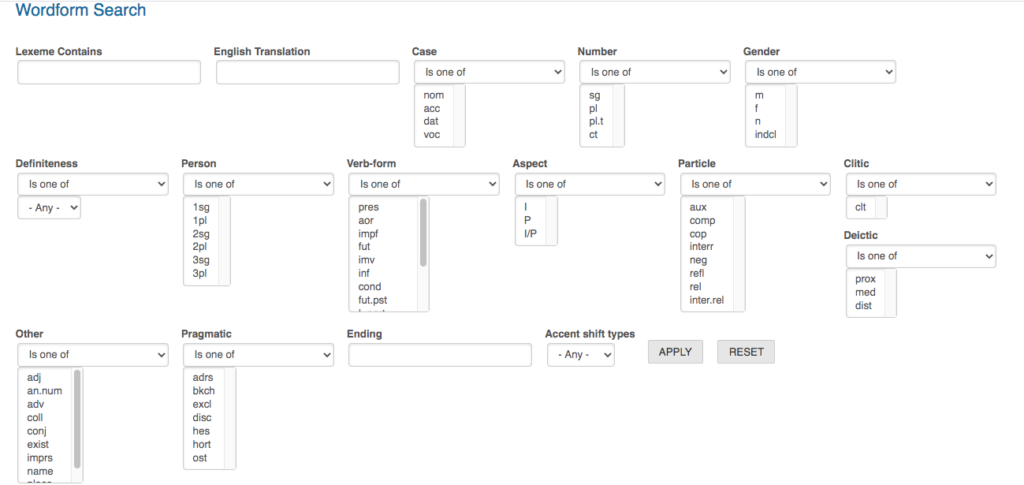

At its most basic, a Digital Asset Management System is a locally-developed digital repository designed to store, describe and manage digital assets of the Libraries. Digital assets are comprised of a primary digital files like scanned images, book pages, audio or video recordings, with varying component parts: metadata, or data about the data that includes information about the origin of the file, specifications and descriptive data used for locating the asset; additional secondary files that can be machine-readable and/or provide additional technical information; and derivatives, such as thumbnail images, other file versions, and PDFs.

The DAMS serves as the central preservation and management hub for Libraries’ digital assets, built by the Libraries Information Technology Support (LITS) team in coordination with staff library professionals, who also manage the operations of the system. The DAMS project began in 2016, and in an effort to prioritize two of our most notable collections, staff at the Benson Latin American Collection and the Alexander Architectural Archive began preparing digital collections for the system.

“The digital asset management system was many years in the making,” says Jennifer Lee, Director of Discovery and Access. “And for many, many years before that it was just an idea, like an item on a collective wish list. Now, it’s become a reality. And over the past seven months in particular, we’ve made excellent progress on adding content.”

The Collections Portal

The Collections Portal serves as an access point on the Libraries’ website allowing users to undertake remote research and study utilizing rich resources that have previously only been available in person or through more time-intensive digitization on demand processes.

Developed in 2018-19 by LITS in close coordination with other Libraries professional staff as a logical progression from the DAMS, the Portal provides students, faculty, researchers and the broader public access to collections that have not been directly available in the past, and the project’s infrastructure creates a framework for a more consistent stream of new digital content in the future. Each item in the portal also contains contextual data – drawn from the DAMS – in order that users may learn underlying information about the material, locate physical counterparts and determine reuse rights for digital files.

The Relationship

The relationship between the DAMS and the Portal can create confusion since both systems deal with the same assets, but it’s useful to think about the interrelationship between the parts. The DAMS is the back-end storage and management environment, where preservation, description and accessibility of the resources are controlled. The Collections Portal draws on the information contained within the DAMS to make some of the content that exists there discoverable and accessible for remote use through a public web interface. The dual structure allows for our staff to determine what is suitable for partial or full public access based on issues like copyright or embargo status.

“These two are separate but closely connected software systems,” explains Mirko Hanke, Digital Asset Management System Coordinator, who has been one of the driving forces behind efforts to refine and build out the systems. “This overall architecture of having two separate systems allows the curators to choose which of the content they’re managing in the DAMS they want to make publicly available.”

Both systems were implemented by LITS staff using open source software components and they built software to bridge the two systems from scratch.

The Processes

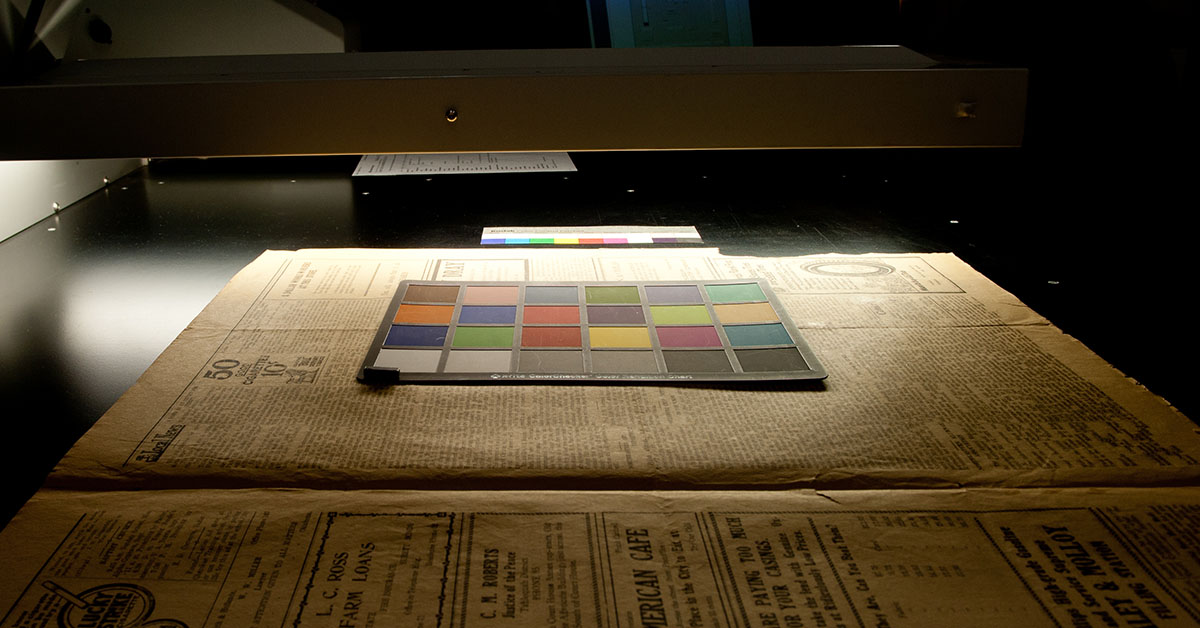

The basic workflow for getting items from the shelves into the systems involves digitization, file management, metadata creation and ingestion.

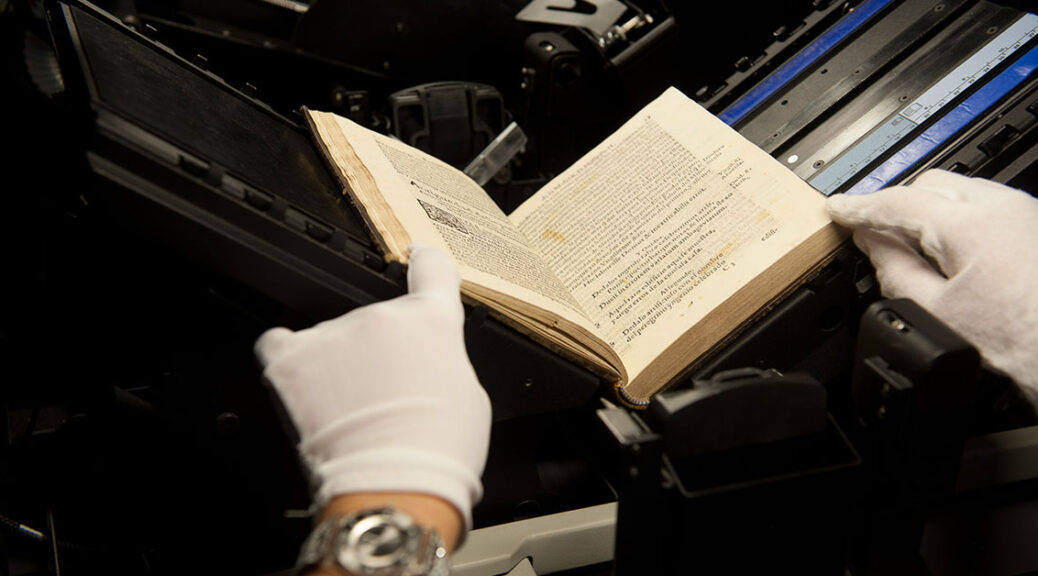

The Libraries has been digitizing physical materials for decades, including thousands of items that were digitized previous to the development of the DAMS, and those files can be retrieved and processed for inclusion in the new systems. Accessing the digital forms of materials can extend the life of fragile special collections and makes near-immediate global access possible. Physical materials are often reformatted as digital files in their entirety to minimize handling and ensure future access to unrequested sections at a later date. Additional processes in digitization allow for the enhancement of usability of the digital iterations, as well, including optical character recognition, making scanned documents searchable and information contained within more easily findable. The automation of many digitization processes makes pagination and file structuring more manageable and speeds up ingestion and thus accessibility of content.

Requests for digitization are made either through a formal submission or directly to Libraries’ Digitization Services, with special priority given to our two notable special collections – the Benson Latin American Collection and the Alexander Architectural Archive – both of which are heavily used by the public and thus have significant back catalogs of digitized materials, making them fertile resources for populating the DAMS and Collections Portal. Special consideration has also been extended to time-sensitive projects, such as those slated for exhibition loan or items that are being or have been retired from other access points.

Once files have been digitized, they are passed through specialized workflows based on the type of content and its historical origin that add and/or enhance metadata, secondary files and derivatives to create singular digital assets that can then be ingested into the DAMS and potentially projected out to the Collections Portal.

Staff professionals working with LITS professionals have developed scripts and processes that can help to speed up the packaging of digital assets both for newly digitized items, but also from previously digitized materials that exist from earlier Libraries efforts. There is ongoing work to track digitization, management and ingestion processes to create ongoing improvements to the workflows.

Hitting the Gas

Realizing the important potential of the two systems for remote users in response to the health crisis, the Libraries reconfigured workflows and redirected staff to accelerate work already occurring to populate and invigorate the DAMS and by extension, the Collections Portal. The first order of business was to formalize workflows to prioritize the digitization and processing of materials.

Resources at the Benson and Alexander Archive proved to be low-hanging fruit for their outsized use in research and because of existing expertise in digital preservation, so projects originating from those collections received significant attention.

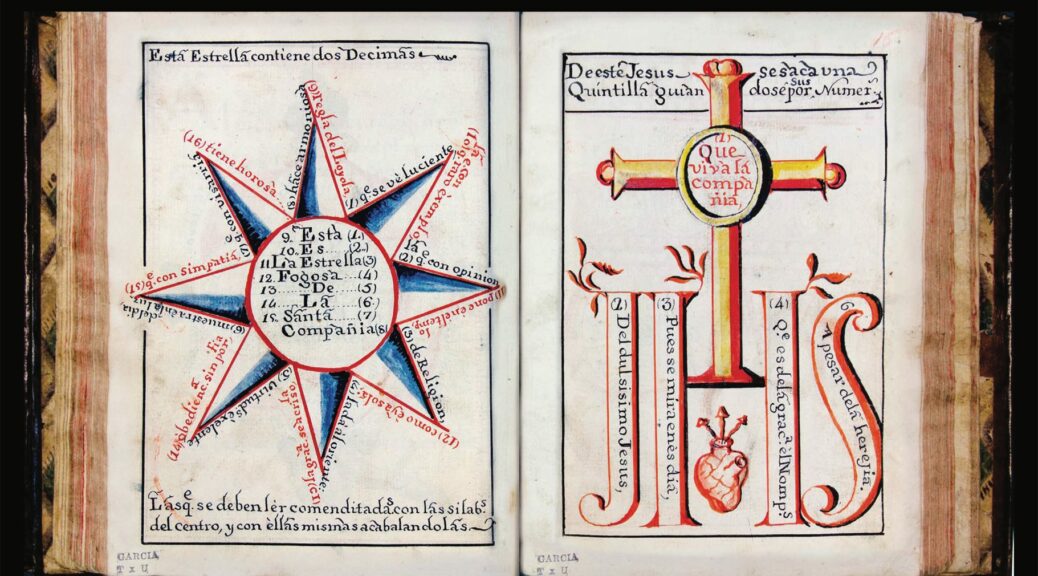

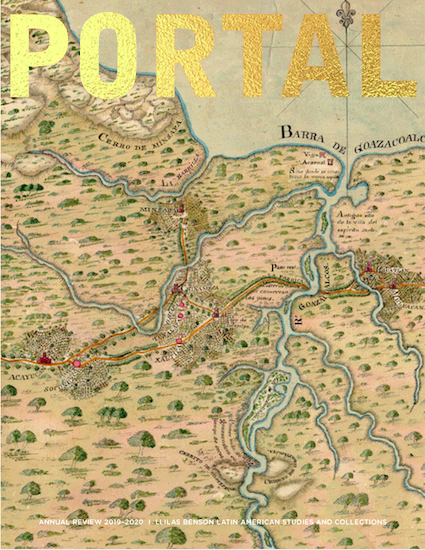

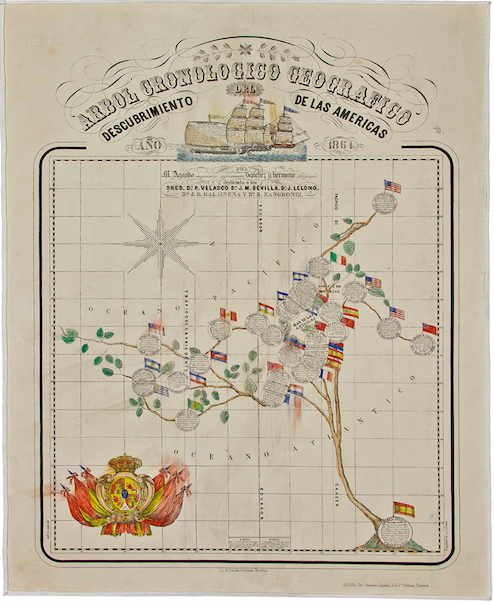

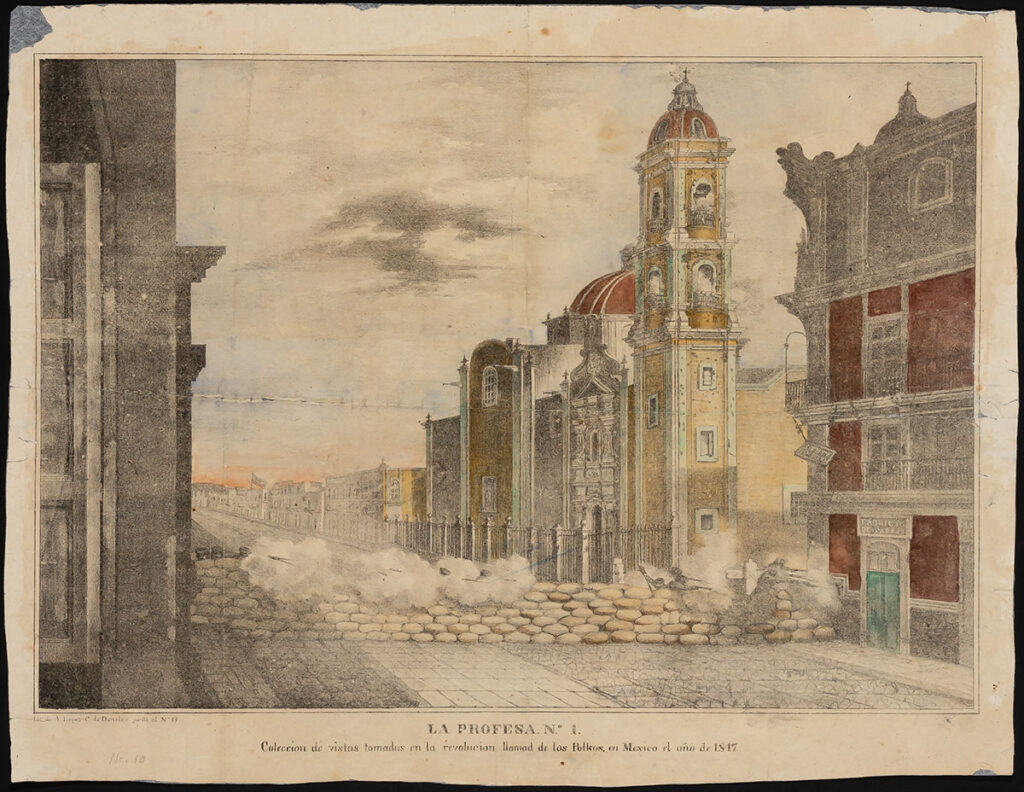

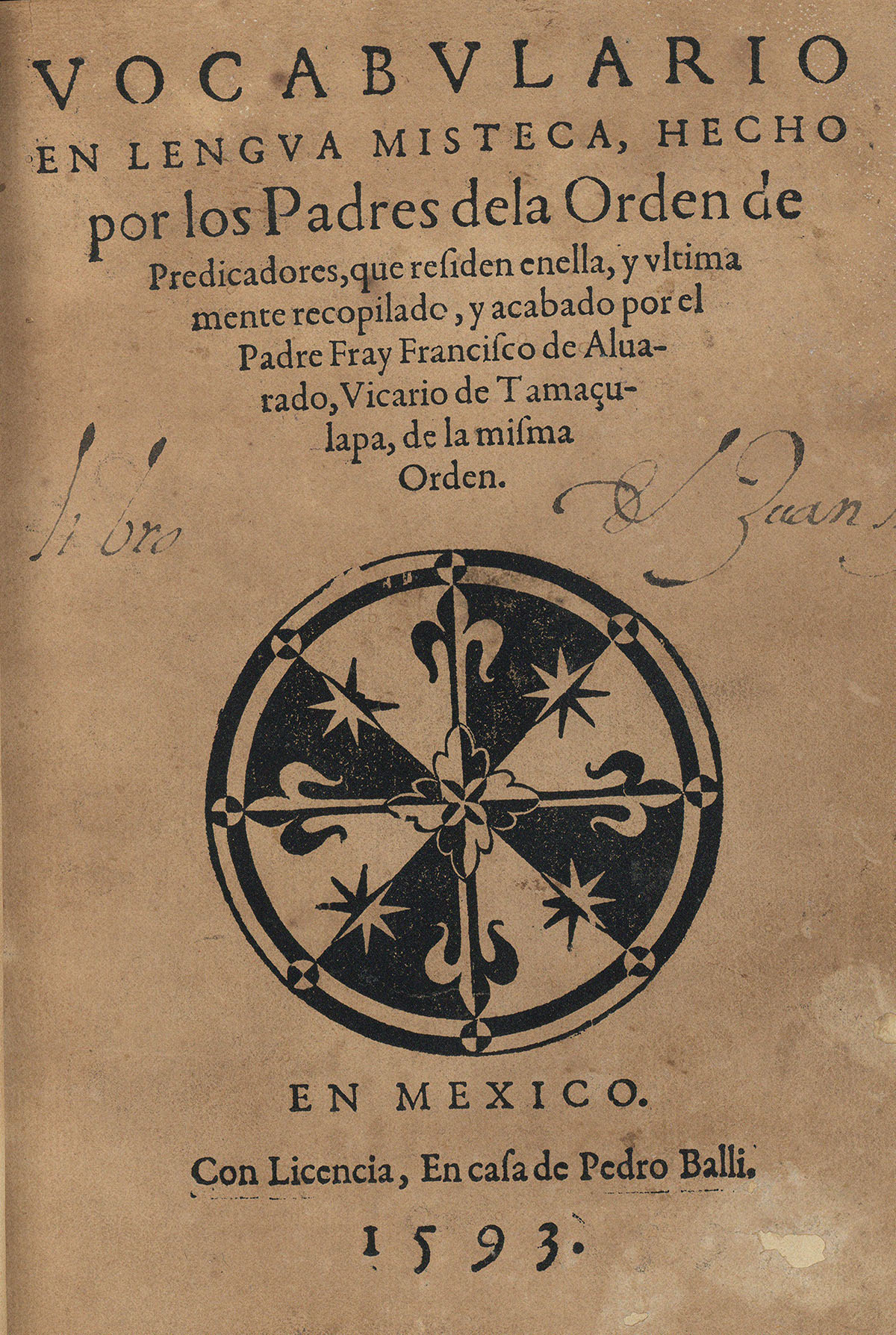

Staff at the Benson Latin American Collection have been working on a project to digitize the Genaro García Collection – the Benson’s massive foundational collection, acquired in Mexico City in 1921 by university representatives on a diplomatic visit. The Libraries will next year be celebrating the 100th anniversary of that acquisition as the establishment of Latin American collections on campus, so the effort to provide online access to this important collection made it a priority for addition to the Collections Portal.

“Because we’ve established some good local practices for collection creation and we have a set of well documented requirements on the DAMS ingest side, it becomes much easier to develop batch processing workflows to prepare scans and metadata for upload into the DAMS without manipulating each collection object, one at a time,” says David Bliss, Digital Processing Archivist at the Benson Latin American Collection.

A team-based approach was coordinated by Latin American Archivist Dylan Joy. Staff Photographer and Library Specialist Robert Esparza spent several months carefully digitizing the Genaro García Imprints and Images collections in their entirety, following a process developed locally at the Benson. Concurrently, GRA Diego Godoy compiled item level metadata based on a template developed by Metadata Librarian Itza Carbajal. Bliss then worked to develop a script for ingesting the scans and accompanying metadata from the collection into the DAMS, bypassing hours of monotonous and error-prone work in favor of a process using existing metadata in a hands-off approach that occurs in minutes instead.

“We didn’t just wake up one day and decide to make our file naming practices more consistent and systematic or suddenly realize that we should be gathering good metadata,” says Bliss. “This kind of scripting work is only possible because significant resources were dedicated to equipment and project staff.”

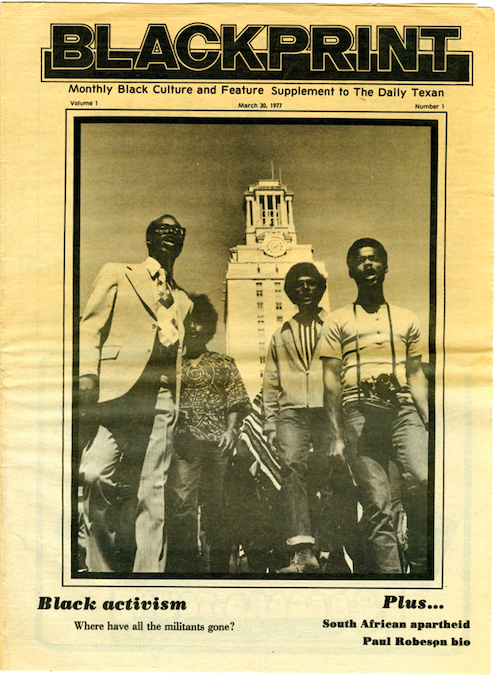

Benson staff, in coordination with Libraries’ Content Management and Digitization Services teams, have worked prodigiously on the Benson Rare Book Collection, including the high visibility Primeros Libros – the first books published in the Americas prior to 1600; so far, 21 full volumes are published to the Collections Portal, with more in process. Libraries Technology Coordinator Benn Chang worked with Benson Latinx Studies Archivist Carla Alvarez to make newly available several hundred previously digitally-preserved photographs in the George I. Sánchez papers, which are now part of the Collections Portal, as well.

“This work really does take a village and there is no one singular workflow or approach that suits all collections,” says Benson’s Head of Digital Initiatives Theresa Polk.

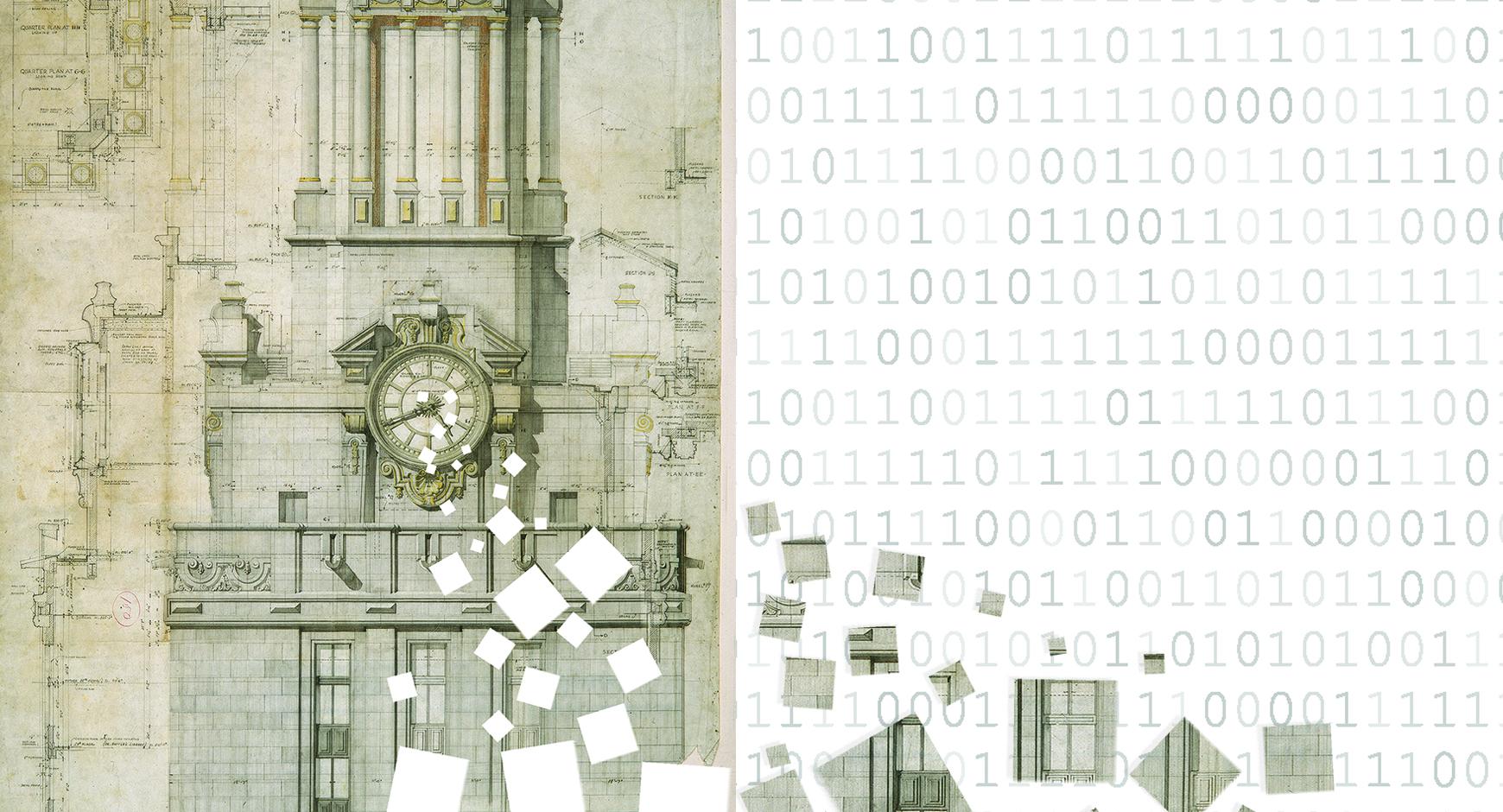

At the Alexander Architectural Archive, staff have been working to process both newly-digitized and legacy digital assets. “Architectural collections staff have worked closely with Digitization Services to adjust our workflow to include ingesting assets and metadata into the DAMS,” says Archivist for Access and Preservation Stephanie Tiedeken. So far, over 21,000 assets have been ingested into the DAMS from the Alexander Archives and Architecture & Planning Library’s Special Collections, and over 2,000 of those have been published into the Collections Portal, including 270 publications and over 1,800 digitized drawings or photographs.

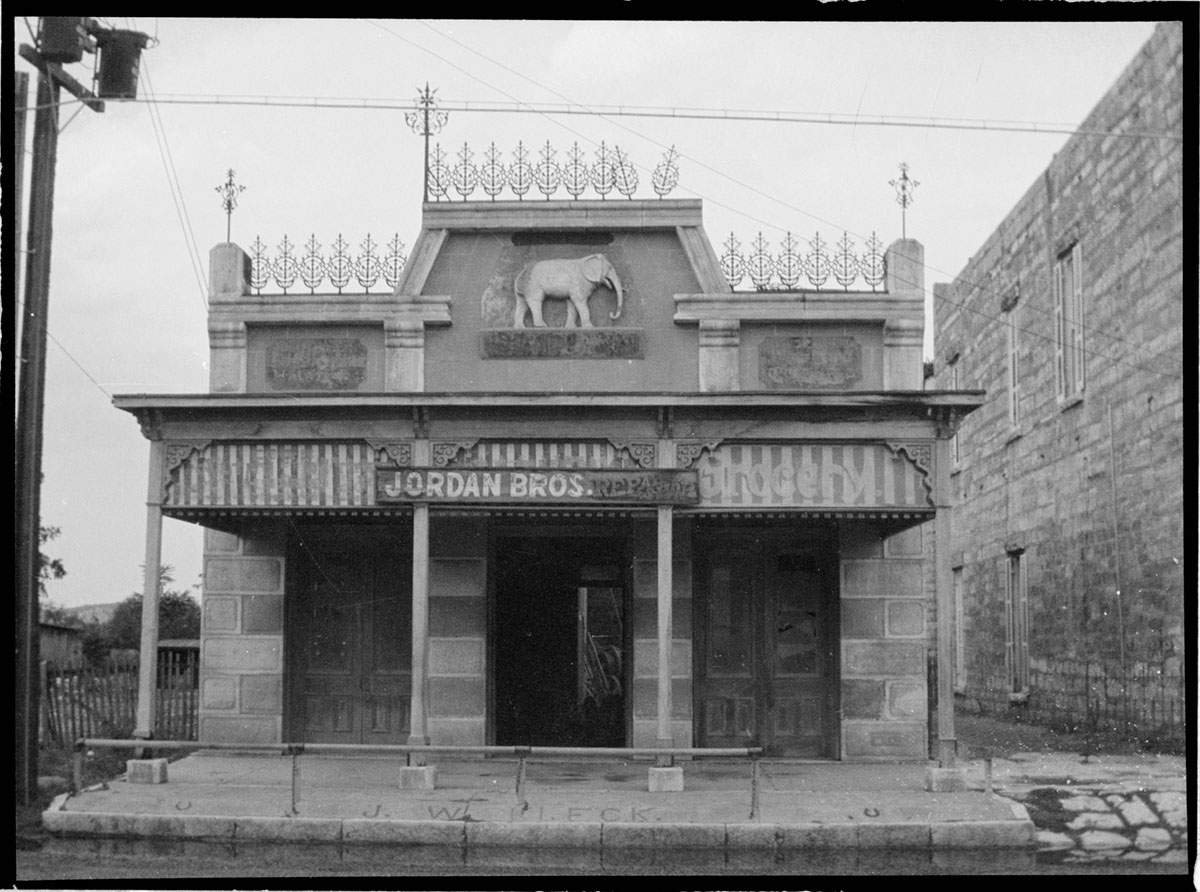

Archive staff are also working to move legacy assets into the DAMS. The Alexander’s GRA, Alyssa Anderson, recently completed a project to ingest 262 legacy images of scanned drawings and photographs from ten sites, primarily missions, in Texas and Mexico images and create MODS metadata. Now that these items are in the DAMS, they are more usable and visible to researchers.

Head of Architectural Collections Katie Pierce Meyer worked with Mirko Hanke and staff from Digitization Services to develop a process for ingesting legacy digitized photographs from the David Reichard Williams collection, a regionalist and architect who documented vernacular architecture in Texas in the 1920s and 1930s. Colleagues from Libraries’ Branch and Borrow Services transferred data from finding aid, added descriptions of photographs, bringing expertise and fresh eyes to these historic images of buildings and places across the state.

Building on transformation processes and documentation work previously done by David Bliss and Benn Chang, and working closely with Mirko Hanke, Pierce Meyer was able to take the data, map it to DAMS metadata fields in the data editing tool OpenRefine, then export it and create individual metadata files for each image. The image and the metadata files could then ingested and published in large batches.

After materials were ingested from the David Reichard Williams photography collection at the Alexander Archive and became available via the Collection Portal, colleagues in Content Management conducted quality assurance on the ingested data and enhanced the metadata. Finally, Alexander Architectural Archives’ Curator Beth Dodd introduced these published assets to historic preservation professionals and donors to the Alexander Archives, who provided additional information to further describe and enhance information about the buildings in the photographs. Over the course of the project, the crowdsourced assistance of many participants have been instrumental to ingesting assets and enhance the metadata, making for a more robust and discoverable resource for future researchers.

“The Williams project has been a particular example of a collaborative, iterative process to transfer our legacy assets to the DAMS and publish them to the collections portal. It has also been a great learning opportunity and we are taking what we have done here to inform future collaborative work with our collections and metadata transformation” says Katie Pierce Meyer.

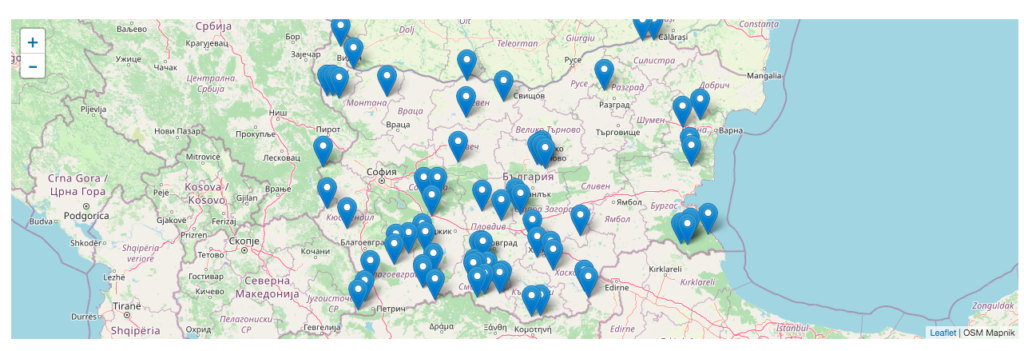

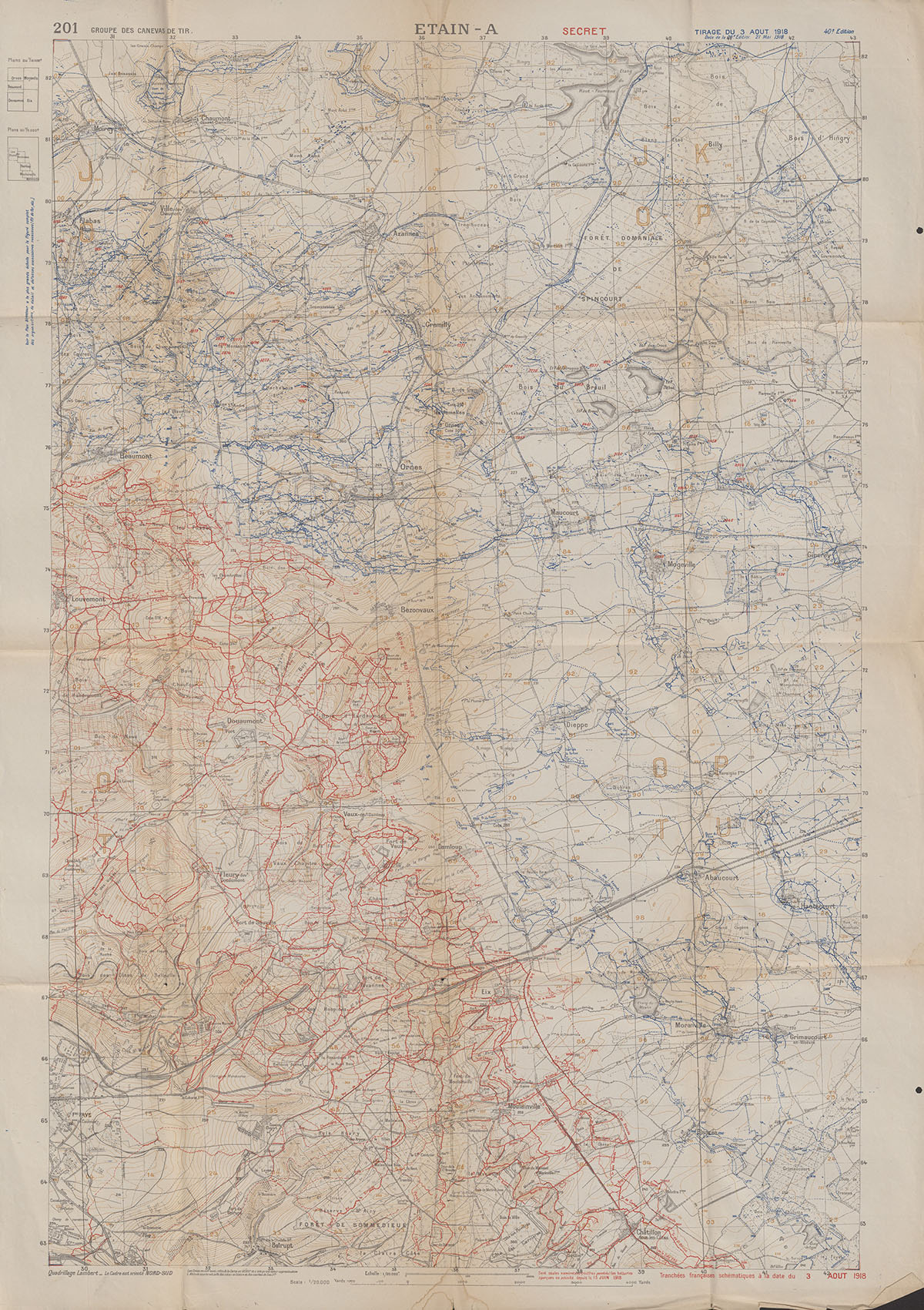

Another extremely visible digital collection has also played a significant role in the growth of DAMS and Collections Portal content. The PCL Maps Collection – which is celebrating its 25th anniversary this year – is perhaps the most heavily used of our collection, largely due to the 70,000 items that are available through the Libraries’ legacy website. Visitation to the online maps has accounted for over 50% of all Libraries’ web traffic at points, and has exceeded 5 million views with consistent frequency. The Libraries’ launched a new website in 2018, and have begun to migrate the Maps Collection into the DAMS where it will be available through the Collections Portal. The legacy website remains active largely to maintain access to the collection, so ingesting the digital content from the Maps Collections is another high priority for the overall project.

The migration of the collection into the DAMS is providing the opportunity to greatly improve upon the associated metadata and, in some cases, to provide even higher quality digital scans for use by researchers. “In the DAMS we can store and serve larger format images, which is a great improvement and there are established organization standards, where the legacy site grew organically from its early adoption roots,” says Maps Collection Coordinator Kat Strickland. “Many of the maps in the collection have made their way here without any context. So being able to show somebody the image and describe with more robust metadata is also going to improve discoverability for people.”

“The DAMS is going to benefit users because collections can be organized in a way that will help users find the context of individual maps by linking to a subcollection of related maps.”

When the university shuttered operations in March and physical access to the Maps Collection was halted, only 77 items had been migrated to the DAMS. A short seven months later, there are over 14,000 maps in the system and Libraries’ staff are currently working on metadata for another 11,600 to make those available.

That experience mirrors the shift in focus since remote work has become the prevailing mode of service at the Libraries and online content has become the primary resources for users. In March, there were approximately 2,500 digital assets available through the Collections Portal. Today, there are over 20,000 assets available through the Collections Portal, and those numbers are expanding apace as more resources are committed to the work and staff adapt innovative approaches to their processes.

“There’s been an eightfold increase in content since March, which is just amazing progress and wouldn’t have been possible without the support of many colleagues,” says Mirko Hanke.