Brittany Rhea Deputy is the Librarian to the Moody College of Communication and the College of Liberal Arts Department of Linguistics. A native Floridian and Texas transplant, Brittany holds an MLIS in Library and Information Science from the University of South Florida and a BS in Public Relations from the University of Florida. She offers a wide variety of teaching and consultation services with specializations in finding data and statistics, analyzing current and historical print and broadcast news coverage, and utilizing research resources and specialized tools. Her previous employers include The University of Alabama, The University of South Florida – Health, and The University of Florida.

So, how did you come to the University of Texas Libraries?

Brittany Deputy: I came to UT Libraries in 2013 after working as a human environmental sciences librarian for the University of Alabama Libraries. Before I became a librarian I worked in public relations and communications for the University of Florida’s Graduate School, so when I saw the opportunity to get back into that discipline but in a new role, I jumped into action. I really loved the job I was in, but I couldn’t pass on the perfect mashup of communications and librarianship that I have in my job here at UTL.

It’s great that you were able to find something that married your interests like that. What’s an average day (if there’s such a thing) for the communications liaison/librarian at UT?

BD: Honestly every day is different. My days really depend on what semester we’re in and what’s happening at that time in that semester. For example, up until last week you probably wouldn’t have seen me much in the PCL because I was teaching over in the Belo or CMA buildings at the Moody College.

Now, the classes are tapering off, but I’m seeing more and more one on one research consultations. These are mostly with graduate students or faculty members, and sometimes with research institutes on campus, who need really specific, in-depth research help and expertise. Then as the month wears on and we get closer to the end of the semester, I’ll switch over to my special projects. Things like the Graduate Research Showcase the Social Science Librarians Team is hosting or a special lecture I’m giving on the history of fake news.

Of course during all of this I’m doing day to day things like answering reference questions, purchasing items for the library collections, and serving on committees and groups as well. I’m never bored that’s for sure!

Tell me a little about teaching at the college. A lot of people mistakenly assume that librarians stay cooped up with the books, but that’s not really the case at all, is it?

BD: Haha, no, that’s not the case at all. I probably couldn’t tell you the last time I handled a physical book. Our jobs are very much online and on the go.

How things go when I’m teaching at the college depends on the class, the department, and the students. The needs of undergraduate students versus graduate students and students in advertising versus those in communication sciences and disorders are extremely different. It’s not unheard of for my first class of the day to focus entirely on how to search databases to find peer reviewed research articles about using computer assisted technology to help stroke victims struggling with aphasia and my second class of the day to center on finding and utilizing data from the census, local maps, and NAICS codes to help students figure out the best advertising strategy for the luxury handbag company they were assigned as a “client.” It’s all so different every time I walk into a classroom, but that’s what makes it the most fun.

Communications studies are sort of all-encompassing in a way that lots of people probably don’t consider. Does it get overwhelming trying to keep up with trends and innovations, especially given the increasingly connected nature of the world?

BD: From the outside it probably seems rather hectic, it can be a lot of work to keep informed of new trends and innovations in any discipline, but if you can discern between what’s hype and what’s helpful, it definitely makes the job easier.

I think this is where my background and expertise really come in handy. I’ve worked in similar jobs, attended the same conferences, and am a member of the same professional associations as the students and the faculty members I work with, so I’ve been where they are and can see where things are going, professionally speaking.

I’m also not alone in my role. I regularly work with librarians at other universities who are in positions like mine, working with students and faculty in communication related fields. We discuss trends, troubleshoot questions, and crowd source ideas almost weekly. A few weeks ago we had a pretty lively discussion about using R or Python to analyze Facebook comments on online news stories. It was pretty cool.

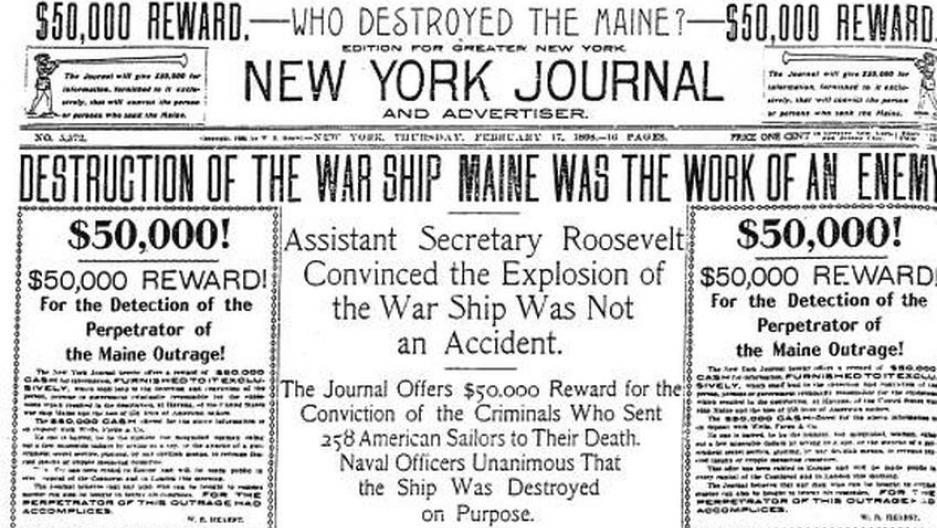

You mentioned a special project, a lecture on fake news, which is a topic of much discussion in the wake of the recent presidential election, but has probably existed for a much longer period of time. What role do you think libraries in general — and the UT Libraries more specifically — play in combating bad information in a world where traditional filters no longer exist?

BD: Fake news has been around for a long time. Historical figures like Marie Antoinette and Mark Antony might have lived a bit longer if it weren’t for fake news in fact. The difference today is our access to it. Instead of graffiti on Roman walls or printed pamphlets in the streets of Paris, fake news stares us in the face from every screen. I mean, there’s probably about five screen devices in my office right now, so that’s a lot of access points!

Thankfully though, the libraries, especially UTL, can help people sort through it all and stay informed of what’s really going on in the world and the communities around them. Librarians are experts at research and evaluation and can teach people how to look at news holistically. It’s tempting to take a news story at face value or maybe even just use a small checklist approach to evaluating it, but in today’s world, with news breaking 24 hours a day, it’s not enough. You really have to be curious and dig deep and that’s were librarians like myself and my colleagues at UTL come in to help. We can walk you through the process and show you some tips and tricks to help along the way.

Now obviously not every person could, or would want to, take a deep dive into every news story they encountered, but even if you do it just once or twice, it can really help you separate the facts from fiction. But if you do fall victim to a fake news story don’t feel too bad. Bad information happens to good people sometimes. I’ve even been tricked a few times!

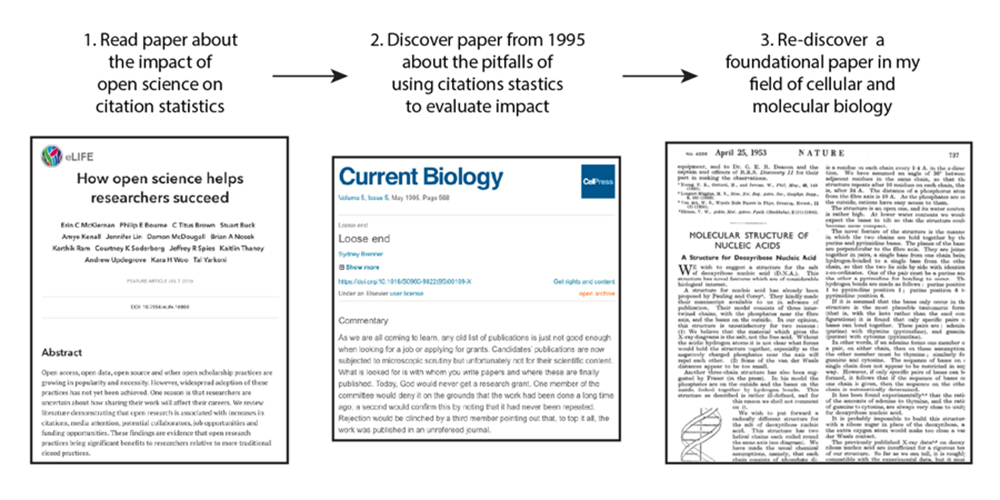

Given that you help people to navigate sometimes complex or obscure information, you probably learn quite a bit that you aren’t expecting. What’s a discovery you’ve made through your work that you’ve kept with you?

BD: I’m always stumbling on to the new and unexpected when I’m working with researchers. It’s really satisfying to find those hidden gems and watch the research story unfold or even completely change because of it. It’s an exciting thing to witness and be a part of. I don’t think I have one specific discovery that means more than any other one, but I will say the first time I was mentioned and thanked in the acknowledgements section of an award-winning book was pretty special. To see my contributions to a researcher’s work in print was an amazing experience.

Validation is always a nice thing, because so much of life is just doing a good job because it’s what you do. What about the future? Where are you in ten years, and what is the job of the future communications librarian?

BD: I wish I could know what the job would look like in ten years! Things move so fast and change so readily it’s impossible to forecast exact trends that far in advance. I think a lot of people might have the assumption that libraries and librarians have served their purpose and are on their way out due to the internet and online access or that it’s just a building that holds a lot of stuff. But that isn’t really true at all. It is true a lot of things are online and it is true the library has a lot of “stuff”, but without librarians to help people find it, sort it, and make sense of it all, it’s just a book on a shelf. Data is just data. Information is just information. People, librarians and researchers working together, are what turn those things into knowledge. And that will always be the biggest and best part of this job. So hopefully that’s what I’ll still be doing in ten years too.