Even before entering the Perry-Castañeda Library, visitors can easily recognize that something isn’t normal. The bank of doors through which students normally criss-cross as they enter and exit the building have a web of stanchions to direct traffic in very specific ways. It’s a subtle change on the exterior that is an indication of what is happening inside the library in this very abnormal semester.

The energy at The University of Texas at Austin with three-quarters of the student population missing is just a pale shadow of what one would feel at any time at the height of a normal semester. Those who have lingered on the Forty Acres after commencement between summer sessions can attest to the feeling of emptiness that contrasts the otherwise bustling walkways, din of voices and, of course, traffic, of the regular class calendar.

In the waning days of each semester, as campus enters the gauntlet of finals, the Perry-Castañeda Library is normally splitting at the seams with students lighting up gate counts at all hours, especially overnight as they make the last surge toward the end of the long term.

Not this year, though.

The health crisis dictated a new, if temporary, way of life at the Libraries and around the university. When campus closed last March and the very real possibility of an extended hiatus settled in, we really had no way to conceptualize what the fall would look like, but as we progressed through the early months of the crisis, it became increasingly evident that the new academic year would not resemble any that we’d ever experienced before.

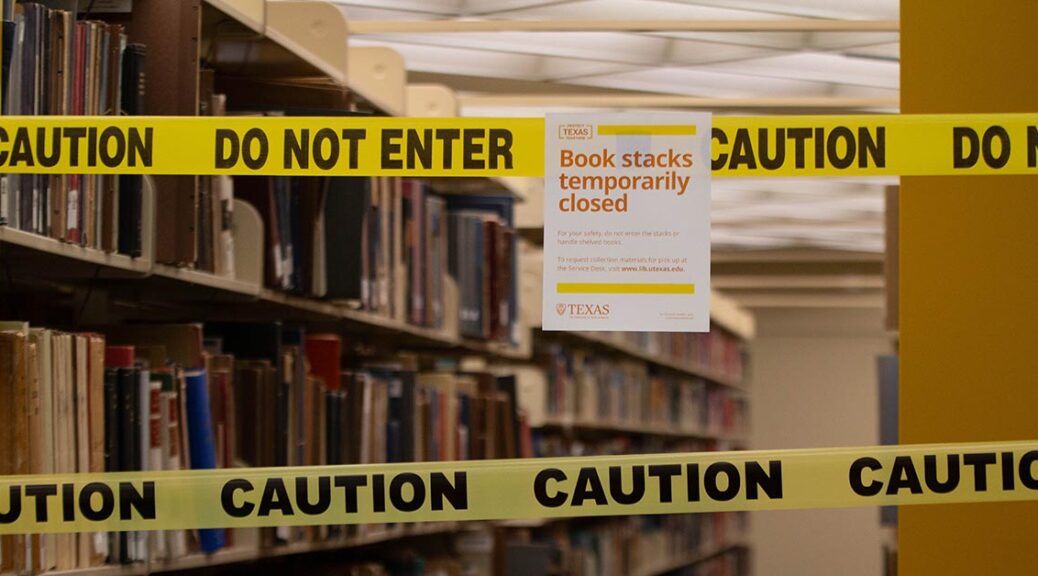

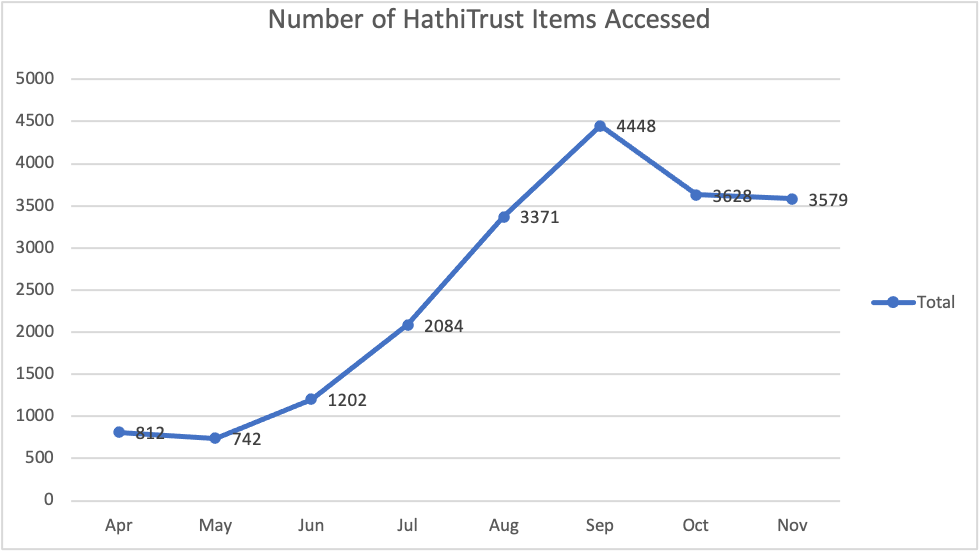

Early in the pandemic, the Libraries had to reorient to services and resources that could be provided remotely, or in service of remote productivity. Consultations and other research help, along with liaison activities became teleconference affairs. Because library stacks were closed to guard against viral transmission and physical resources wouldn’t be readily available, the Libraries coordinated digital access to many of the items that would remain dormant on the shelves through our partnership in HathiTrust – a collaborative of academic and research libraries preserving 17+ million digitized items. Due to copyright concerns, this meant that those physical items owned by the Libraries that were available digitally through the partnership could temporarily only be used in digital format to guard against any violations that could end the Libraries’ overall access to the repository.

Number of HathiTrust items accessed through the UT Libraries.

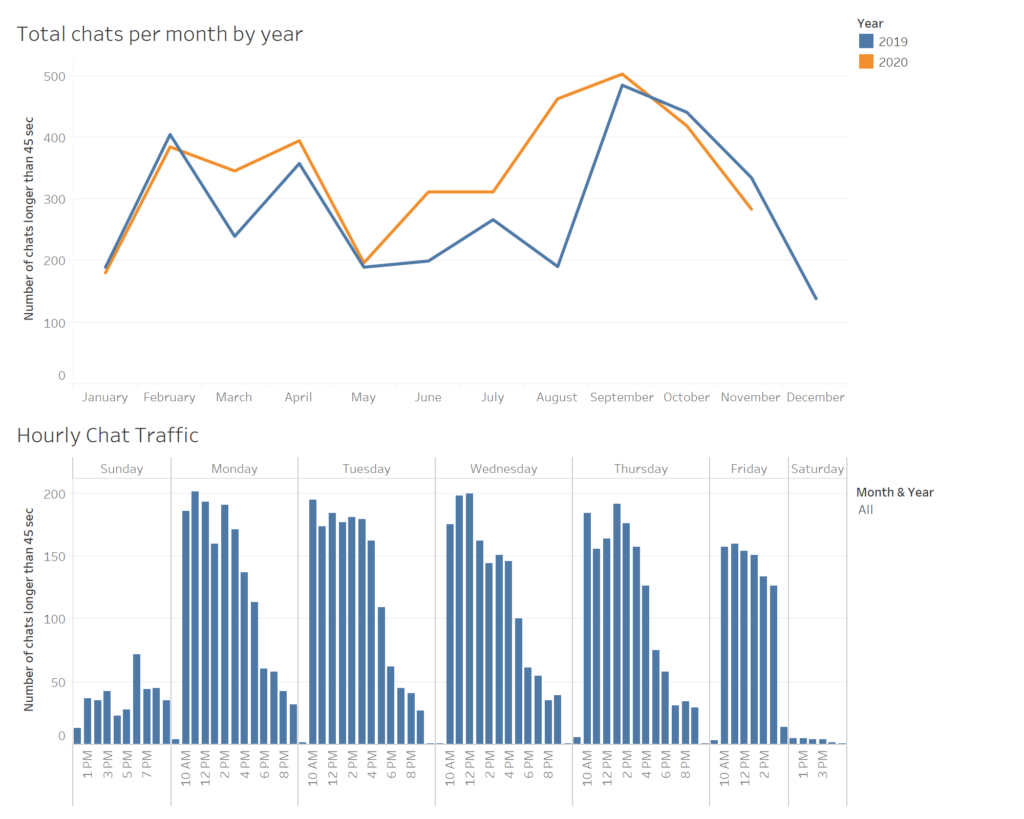

Libraries’ staff continued to provide remote support for research help and the Libraries’ Chat service saw an initial sustained bump in activity. Teaching and learning staff – who normally do a fair share of in-person instruction and support for classroom learning – found innovative ways to participate at a distance. One librarian worked with an Undergraduate Studies first-year class professor to become more embedded in the course than usual in an effort to ensure that the students felt just as connected to and knowledgeable about campus and the Libraries as they would during a normal semester. In addition to supporting the research component of the class, the librarian hosted an online scavenger hunt in ZOOM as a engaging way for students to learn what resources and services the Libraries have now and in post-pandemic times.

Usage data for Libraries’ Chat.

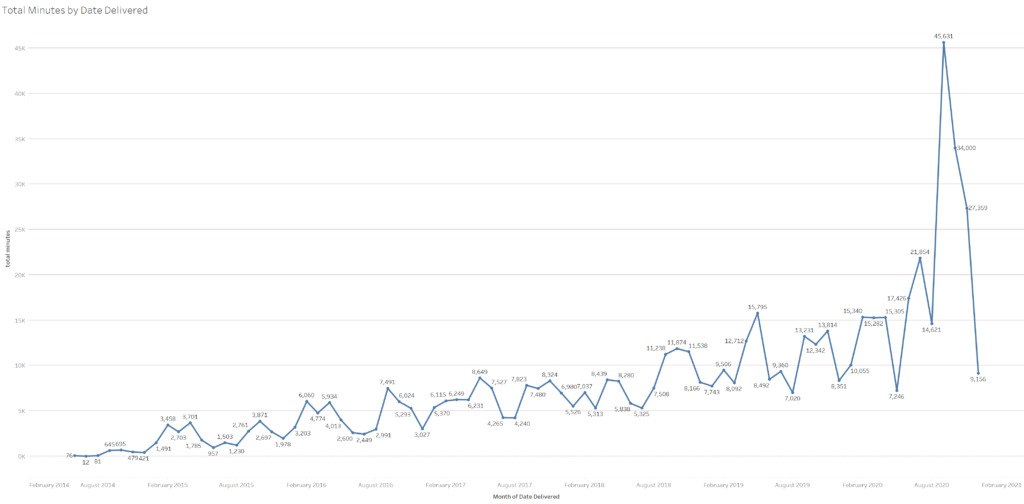

While use of the physical collections necessarily flagged, one of our underutilized services saw a huge increase in traffic. The Libraries’ Captioning and Transcription Service helped respond to the shift to web-based learning by ramping up efforts to meet the needs of online classes with accessible transcription and captioning for campus. In March, the service racked up about 15,000 minutes of captioning; by end of the spring semester they were closing in on 20,000, and peaked just over 45,000 minutes in September.

Total minutes of media captioned/transcribed by Libraries’ Captioning and Transcription Services.

By August, after months of migrating our services and resources to a primarily online-based enterprise, the Libraries and the rest of campus reopened with limitations for the fall semester. While a significant segment of resources and services were only accessible through our website, the decision was made in coordination with UT administration to reopen limited library spaces, primarily for scaled-back in-person services, and as a setting for student study and participation in online classes. The entry level of the PCL provided for those needs for the first few weeks before a decision was made to expand study areas to the 4th and 5th floors of the building. The historic reading rooms at the Life Science Library – the Hall of Texas and the Hall of Noble Words – were both opened solely for student study and online classes for those students who returned to campus for the semester.

Facilities staff from the Libraries spent a painstaking amount of time over the summer in preparation for the return of students to the PCL, reorganizing furniture to encourage social distancing, installing a forest of wayfinding directions for managing the flow of people through restricted spaces, erecting plexiglass dividers as protection for frontline workers and locating sanitization stations strategically throughout the building for users.

Capacity at PCL was initially set for 400 on the entry level, but expanded to 700 when the upper floors of the building were reopened for additional study space.

“The fall semester planning and preparation that was conducted over the summer proved to meet all of our needs and expectations,” says Geoff Bahre, Libraries’ Manager of Facilities and AV. “We planned to have approximately 700 patrons in PCL at one time for which we purchased personal protective equipment (PPE), and designed our spaces to support that number.”

A capacity counter was displayed at the PCL entry and replicated on the Libraries’ website to let visitors know whether they would be admitted, but visitation to the reopened spaces began at low levels and never elevated to a point where capacity limitations had to be enforced, remaining below 50% the entire semester.

“This semester the library has been considerably less busy, and quieter,” says Evening Service Desk Supervisor Stephanie Lopez. “Normally we see thousands of people a day wandering through the building and chatting with friends or asking for research help for projects, but none of that is happening now.”

Thanks to legwork over the summer, the Libraries were able to modify the retrieval service – Pick it Up – so that the campus community would have access to the bulk of physical collections, except that portion restricted by the HathiTrust agreement. PCL became the hub for distribution, and people were able to get their hands on sought-after volumes that had been embargoed by the crisis, while quarantining plans were instituted to insure that our resources weren’t inadvertently contributing to the spread of the coronavirus.

While the limitations are not optimal for everyone, users have been understanding.

“Most people are just happy that we’re open. We’ve definitely had a few folks upset with some of our changes, but that’s been pretty rare and we’re very grateful,” continues Stephanie Lopez. “The comments we get at the desk are from people who are so happy to be checking out books again, and from students who are glad for a change in scenery for their ZOOM classes.”

In order to gather information about how efforts to adapt to the crisis were being taken in practice, Libraries’ Assessment experts took stock of patron perspectives in a user survey late this semester. The Libraries received mostly positive marks, with some expected criticism of limited hours, space, stacks access and safety concerns. Some of the participant feedback included:

- “Could not look through books because the section I wanted to look was on a restricted floor.”

- “It was difficult wearing a mask for multiple hours.”

- “I love that I could request books and that they would be ready at the desk when I arrived! Thanks so much to library staff for keeping that up for us.”

- “I think you should be able to study with at least one other person. It makes it hard to do well in school without studying with somebody.”

- “I noticed a lot of students take off their masks once they were seated. I think the PCL had great safety measures put into place, but I think they should have done better ensuring people followed them, especially the mask wearing.”

- “I think longer hours would be an amazing addition since so many facilities around campus are closing earlier.”

- “I think the way you have been conducting things is great. The online counter that keeps track of many people are at PCL is really helpful. Y’all should keep that even after COVID-19 is over.”

Regardless of the extent to which the Libraries were able to transition in the face of crisis, the prevailing feeling is that everyone is anticipating a return to regular operations.

“I used the libraries far less than I normally would if we weren’t in a pandemic,” explains Associate History Professor Aaron O’Connell. “I usually browse the stacks, and even hold class sessions at PCL to do research methods hands-on work. None of that was possible this past semester, so naturally, I am eager for PCL and the rest of UT to return to normal.”