Based on exhibition text by Gilbert Borrego

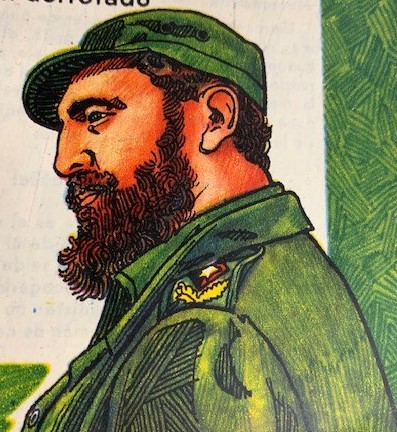

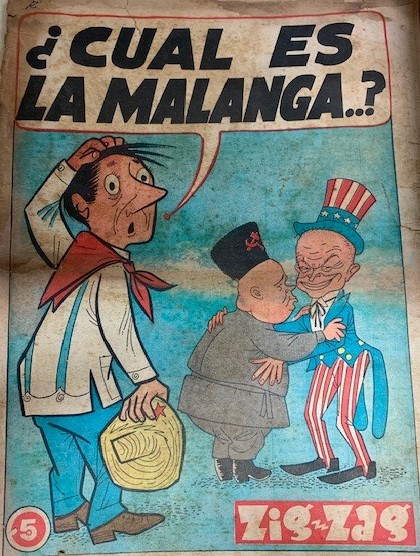

The publishing industry of Cuba experienced a seismic shift in 1959 when Fidel Castro won a revolutionary war against dictator Fulgencio Batista. With this change, underground and subversive media creators of the Batista era became an important part of the new socialist culture. This helped to mobilize the masses in support of the new Castro government and against U.S. capitalistic ideology.

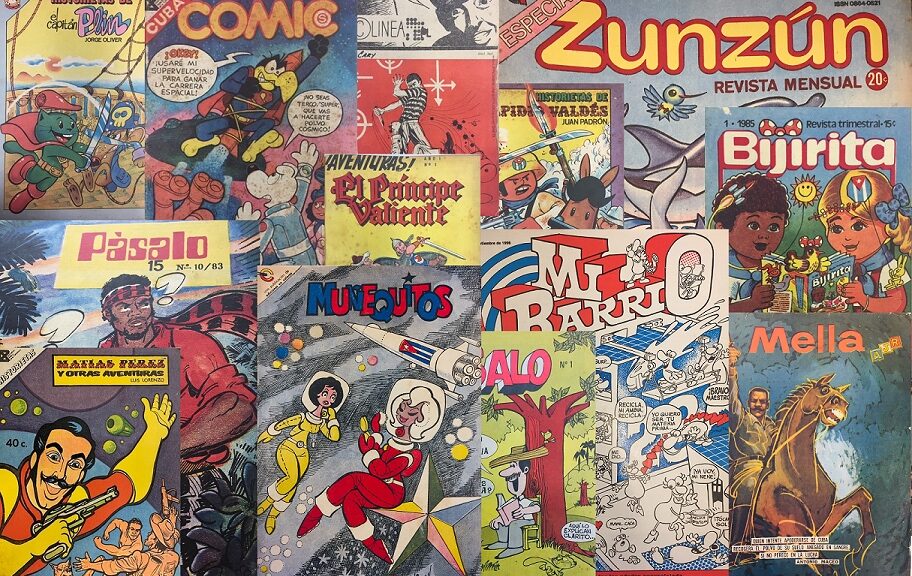

Cuban Comics in the Digital Era examines the art and history of Cuban comics after the successful 1959 revolution, highlighting the creators, characters, heroes, and anti-heroes of Cuba. It also touches on the triumphs and failures of the publishing industry and how Cuban artists today struggle to keep the genre alive.

These materials are part of the Caridad Blanco Collection of Cuban Comic Books, acquired in 2018. Blanco, a Havana-based artist and curator, collected over 700 examples of stand-alone comics and newspaper supplements created between 1937 and 2018.

The Birth of Cuba’s Revolutionary Comics

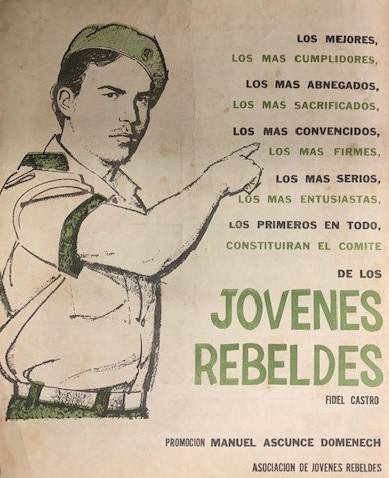

Key to the process of planning a new nationalistic government was the cementing of a new socialistic cultural identity in the minds of the Cuban populace. Radio, television, and print media (including comics) helped to mobilize the masses.

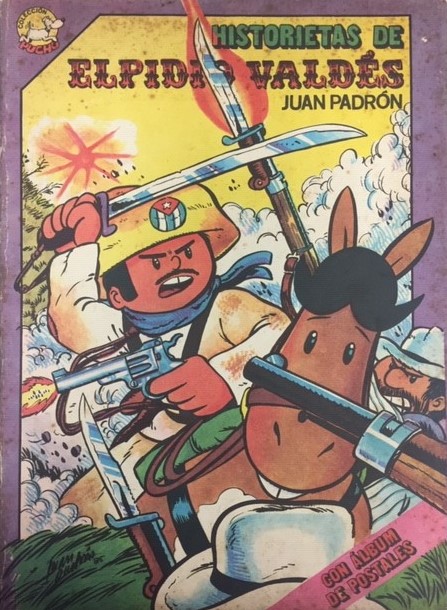

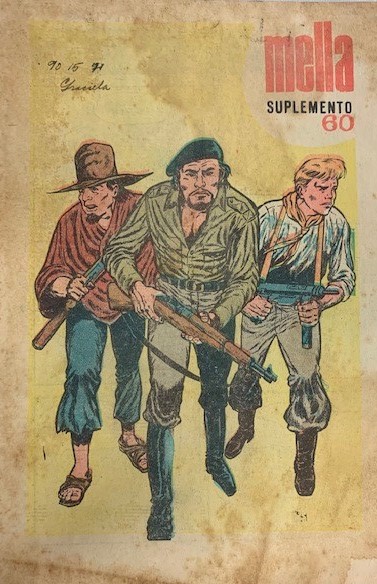

A new world opened up for the creators of comics, who now had the singular purpose of supporting their new government while still appealing to their readers. In this early era, many of these readers were children, who continued to consume U.S.-created comic books and the ideals that went with them.

Widespread suspicion held that beloved American comics were imperialistic indoctrination tools for Cuban children. In response, the new Cuban government began utilizing comics as a means to teach values that aligned with revolutionary doctrine.

Cuban-created comics replaced American ones on the shelves. These works appealed to highly literate youth. Mixing adventure, comedy, and the ideological tenets of the new government, they portrayed revolution as necessary and exciting, especially for the country’s youth.

This exhibition was curated by Digital Repository Specialist Gilbert Borrego and is part of his fall 2019 Capstone Experience course in partial fulfillment of his MSIS, School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin. In addition to the physical exhibition, Borrego curated a richly illustrated online exhibition.

About the Curator

Gilbert Borrego is currently the Institutional Repository Specialist for Texas ScholarWorks at UT Libraries. He has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in anthropology from Stanford University and will soon complete his master’s in Information Studies at UT Austin. He is passionate about archives, libraries, museums, metadata, and history.

Cuban Comics in the Castro Era will be on view in the Benson Latin American Collection main reading room, December 6, 2019–March 1, 2020.

Read more about the Caridad Blanco Collection of Cuban Comics in LLILAS Benson Portal.