One wouldn’t necessarily expect to find a poet in the stacks of a science library, but then again, creativity often occurs in the least anticipated of places.

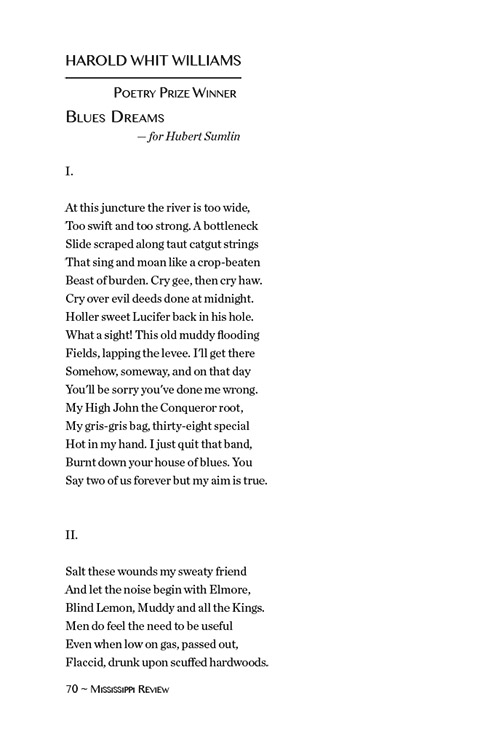

The Life Science Library boasts among its staff a prize-winning poet, as Library Specialist Harold Whit Williams has garnered praise for his work, which is both a catalog of his experience as a musician, and reflective of his southern heritage. His most recent collection of poems, Backmasking, earned Williams the 2013 Robert Phillips Chapman Poetry Chapbook Prize from Texas Review Press, and his poem “Blues Dreams,” received the 2014 Mississippi Review Poetry Prize.

In some ways, it would seem to make perfect sense that Williams would understand the finer points of cadence and pentameter — he’s also the guitarist for notable Austin pop band Cotton Mather.

Williams’ first collection of poetry, Waiting For The Fire To Go Out, was published by Finishing Line Press, and his work has appeared in numerous literary journals.

Whit kindly indulged a line of questioning about his poetry, his music and his life at the Libraries.

![]()

When did you start writing poetry? Was it an outcropping of your music?

Harold Whit Williams: I’ve been writing poetry off and on since college days, but started giving serious attention to it, and publishing, now for about seven years.

Strange, but poetry is a totally separate thing to me from songwriting. As a guitarist first, my songs, or the guitar parts I play in Cotton Mather, happen musically first. Then lyrics come later. But with poetry, it’s all wordplay from the get-go, and the musicality in the words themselves tend to direct where I go in a poem.

Does the inspiration for poetry and music come from the same place, even though the jumping off point is different? Or are they driven by different urges?

HWW: Good question. What makes me plug in an electric guitar and make loud horrendous noise has to come from a much different urge than the one making me get to a quiet place, alone, to jot down a poem.

%CODE1%

Well, that makes sense. Speaking of contrasts, how did you wind up at the Life Science Library? We’ve had a lot of musicians employed at the Libraries over the years. Maybe you can shed some light on why that particular artistic temperament gravitates toward libraries?

HWW: I wound up at Life Science after working off and on for various Austin Public Library branches over the years. I wanted a change of pace, from a public setting to an academic one. I also worked part-time at a public library in Alabama, when I was attending college.

I’m not exactly sure why certain creative types gravitate towards library jobs. For me, early on, it was simply a wonder to be surrounded by shelves and shelves of great books I’d never read, books that I would hopefully get a chance to read, and be inspired by – whether fiction, nonfiction, or poetry.

I wonder if it’s not the same for the other musicians who’ve graced our muster roll, as well. They all seem to be folks who’ve had multiple areas of inquiry, and it may be that the proximity to so much information creates avenues of exploration.

At any rate, I haven’t seen your first book, but “Backmasking” has a very distinctive voice to it. It’s almost like half road-weary musician diary, half reflections on rural southern life with a little spiritual sparring sprinkled in for good measure. I know that’s probably a ridiculous simplification, but as a Texan with rural roots, there’s a familiarity to the subject matter that I find really compelling. Any idea where that comes from?

HWW: Not a ridiculous simplification at all – that’s it in a nutshell. That should’ve been a backcover blurb.

A few years back, I attended the Sewanee Writers’ Conference in Sewanee, Tennessee. A fantastic experience. I got to attend lectures and readings by poets such as Mark Strand, Mary Jo Salter, and others. The poet Andrew Hudgins was leading my workshop, and his main criticism of my writing, at that time, was that I was just too “southern”, that I should try harder, dig a little deeper past the kudzu and wisteria and granddaddy working the coalmines, etc. He was right, and I’ve since tried to delve deeper into my gray matter, to get past the easy imagery, to get at something unique, maybe something not said yet.

But for anyone writing, whether poetry or short stories or whatever, you of course draw heavily on past experiences – traumatic, peaceful, enlightening. For poetry, this usually gets filtered through language and imagery that is more dream-like, which makes it even more personal. And because of my upbringing in small town and rural Alabama, and being involved in music, both sacred and secular, my poetry is, for better or worse, infected with this “southernness”.

Tell me a little about “Blues Dreams,” your poem that earned the Mississippi Review Prize. The tone of the poem almost had me believing that Hazel Motes was going to tap me on the shoulder when I was reading it. What was the inspiration?

HWW: I’m honored that it made you think of Flannery O’Connor. But I would say that the inspiration for the writing style of “Blues Dreams” came from the stream-of-consciousness ramblings of the late Arkansas poet Frank Stanford. He was a tragic figure, taking his own life at an early age. He’s now a pretty well-known and influential poet, but during his life he was fairly obscure.

As a rock and roll guitarist, I’m a huge fan of the Delta blues, of course. I spent countless hours in my youth playing along and listening to Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson records. So as far as the inspiration for the theme of the poem, I guess I wanted to tap into a voice that was one part me, and one part some old gut-bucket bluesman. Also, I’d noticed that I had not yet written a longer poem, or a poem presented in multiple sections, like this one. And so I challenged myself to do that. Nowadays, it seems like almost everything I’m writing is a part of some larger piece. I find it harder now to just sit and write a single poem that’s unconnected to something bigger. It’s just a phase, I’m sure.

A Southern Gothic influence is definitely apparent in your work, but certainly any musician worth their salt has to tip a hat to Robert Johnson and his successors, so why not do it both in your music and writing? Now that you’ve had success in both of those pursuits, what’s next for you?

HWW: My next poetry collection, Lost in the Telling, will be out summer of 2015 from FutureCycle Press, and I’m currently shopping around a newer poetry manuscript, hopefully for 2016 or so.

As for music, Cotton Mather has a stockpile of new material recorded, so we should have a record out next year, hopefully. Also, I play solo acoustic sets on occasion, as a duo with multi-instrumentalist Jon Bookout. In fact, we recently played a few songs alongside a poetry reading I gave at the super-cool local literary shop Malvern Books. I’d like to do more of that in the future, combine my songs and poetry in one event.

Marrying the two forms is a great idea, especially if you have some crossover between the two, which is obviously the case for you. With the new UT Poetry Center open here at PCL, maybe we can coax you over for a show. It sounds like you’re on a roll. Keep us apprised of the next volume, and thanks for talking with us.

HWW: Thank you for your time. I appreciate it.

![]()

Williams will be reading his poetry as part of the Kraken Reading Series at Paschall Bar in Denton, Texas, at 6 p.m. on September 13.