Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the UT Libraries Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of, and future creative contributions to, the growing fields of digital scholarship.

I had the lucky opportunity recently to catch Nickoal Eichmann-Kalwara’s presentation on the University of Colorado’s Digital El Diario project at the UC San Diego Digital Initiatives Symposium wherein she advocated for the use of “minimal computing” to achieve “archival justice.” Deeply inspired by her comments but woefully ignorant of the corpus on minimal computing within DS/DH (what seems a combination of activist- and digital-turn on the “less process, more product” concept in archival work), I took it upon myself to learn more as I struggle with the constant nagging tension between achieving the immediate task at hand (“will a simple Google chart effectively communicate my point?”), exploiting technologies to their fullest extent (“boy, I sure bet I would impress folks if I used a sexy Tableau dashboard”), and justifying resources (“this will cost how much??”). When, I wondered, is less actually more in DS/DH, when is more actually more, and how should we negotiate those differences?

Way back in 2017, Roopika Risam and Susan Edwards argued (in “Micro DH: Digital Humanities at the Small Scale”) that the fixation of everything “large” is not conducive to justice across our institutions, our staff, nor our data:

“Digital humanities practices are often understood in terms of significant scale: big data, large data sets, digital humanities centers… This emphasis leads to the perception that projects cannot be completed without substantial access to financial resources, data, and labor… While this can be the case, such presumptions serve as a deterrent to the development of an inclusive digital humanities community with representation across academic hierarchies (student, librarian, faculty), types of institutions (public, private, regional), and geographies (Global North, Global South).”

I found their argument compelling and wondered where I had seen these tensions in practice. As a South Asianist, I had to look no further than the uniquely colonial way of knowing—lexicography–and the uniquely 21st century way of access–digital reformatting.

For over 20 years, the Digital Dictionaries of South Asia (part of the Digital South Asia Library at the University of Chicago) has arguably been the gold standard for online South Asian language dictionaries. Recognizing the inadequacies of OCR tools to convert images of most South Asian scripts to accurate text data, the DDSA has utilized strategies such as “double blind keying” to produce highly accurate digital editions of established and respected dictionaries. The process is time-consuming and expensive but produces trusted full-text data that can be used and manipulated in a variety of ways, including those beyond dictionaries. The institutional positioning of the University of Chicago has allowed for many successful grants over the years to fund DDSA, including those from the US Department of Education, the Mellon Foundation, the Association for Research Libraries and others. The DDSA is truly extensive in scope and in impact.

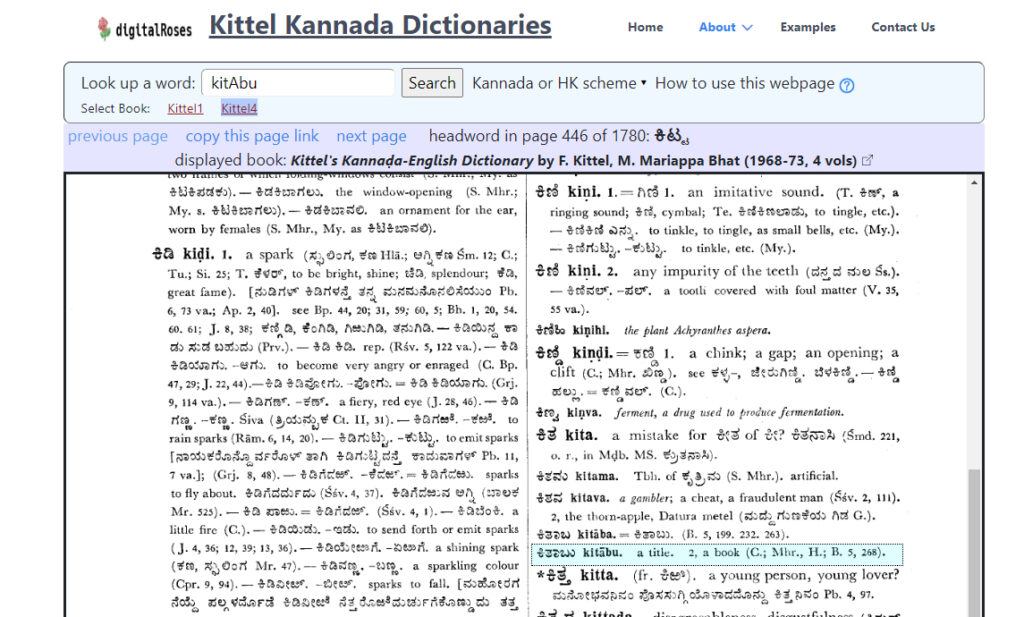

At the other end of the spectrum is the DigitalRoses project. In this pilot, an individual researcher, Gil Ben Herut, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of South Florida, presents another approach to digital dictionary making. Rather than seeking a fully searchable, text-mineable dictionary, Herut suggests that simple encoding that operationalizes headwords alone (rather than the full-text) for navigation within a dictionary is sufficient for most user applications. Using target words, the DigitalRoses approach “resolves a common problem in OCR text ingestion through the utilization of manual indexing of the first entry word on each page in physical media, [thereby… ingesting dictionaries at a fraction of the time and cost of full digitization,… streamlining searching by allowing partial, wildcard and fuzzy searches, and maintaining the richness of the printed layout.”

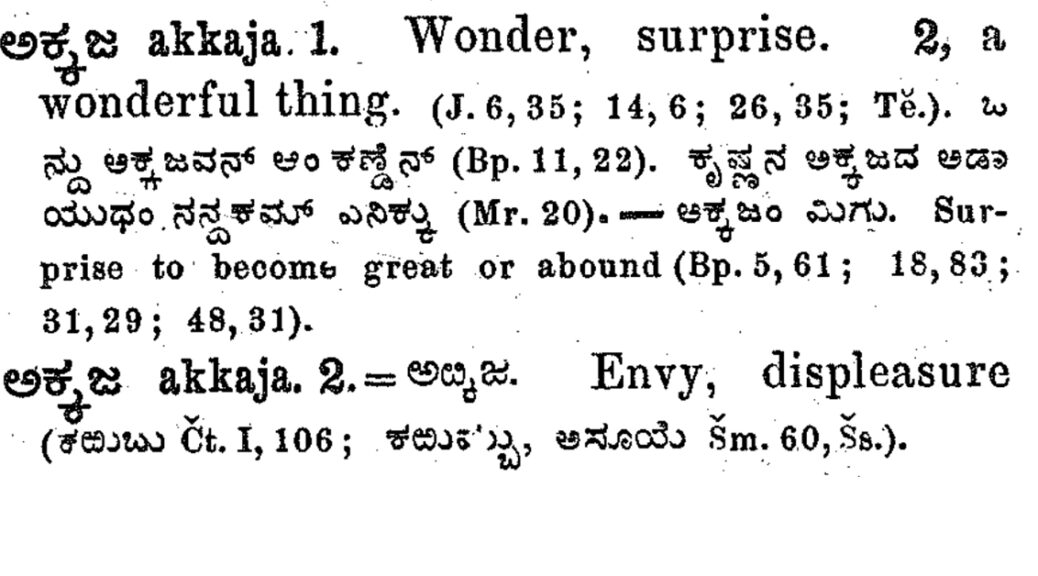

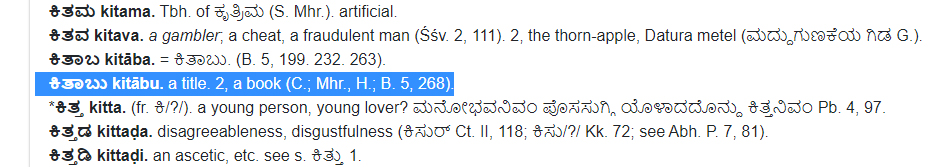

In comparision, then, we have two approaches to the same problem and therefore two solutions. See, for example, a search for the Kannada word for “book,” Kitaba/ಕಿತಾಬು, in the DDSA version of Kittel’s Kannada-English Dictionary and in the Digital Roses version.

The thoroughly meticulous approaches used in the DDSA model produce a robust and unique digital experience built on fully manipulatable, multiscript data while the simple imaging and only partial inputting of the DigitalRoses project produces a quick digital surrogate to the analog counterpart.

Turning back to “minimal computing,” these two projects offer up models to complicate our understanding of who gets to do what and how in our technologically informed research. Grant funding allows for big data and big research at big institutional levels. Minimal computing allows individuals and less resourced cohorts to also meaningfully contribute to the field. Both approaches have the potential to positively impact users and the creation of new knowledge.

I encourage you to consider where you fall on this debate: is less more? Is more more? And when does it matter?

For more on minimal computing, justice through DS/DH, lexicography, and Kannada, see:

Constance Crompton, Richard J. Lane and Ray Siemens, eds. Doing digital humanities: practice, training, research (London; New York: Routledge, 2016)

Howard Jackson, ed. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Lexicography / [edited by] Howard Jackson. (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022)

Ferdinand Kittel and Mariappa Bhatt. Kittel’s Kannaḍa-English dictionary. (Madras: University of Madras, 1968-1971)

Roopika Risam. New digital worlds: postcolonial digital humanities in theory, praxis, and pedagogy (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2019)