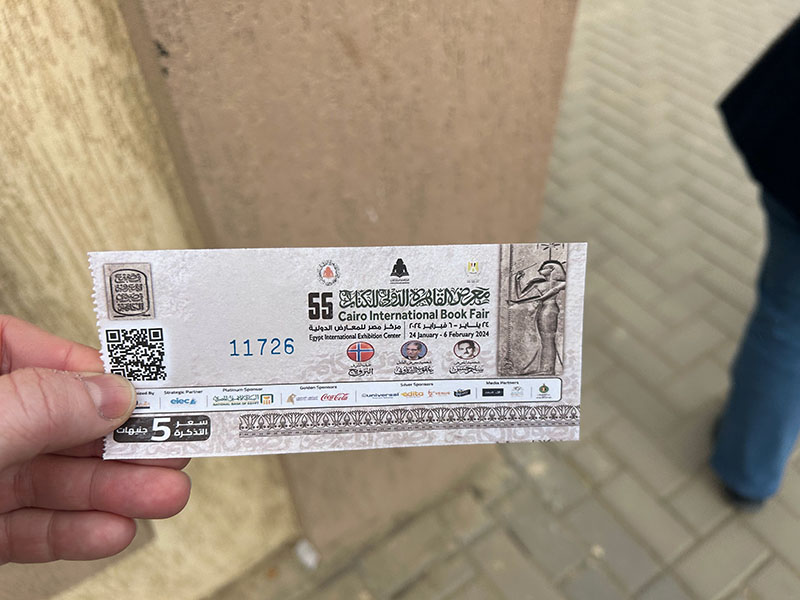

One of the best parts of serving as the Middle Eastern Studies Librarian for UT Libraries is making and maintaining relationships with scholars, publishers, and vendors. I take advantage of any opportunity to travel to continue fostering these relationships, and my trip to Egypt in late January was no different. I was lucky enough to be able to travel specifically for the Cairo International Book Fair. Over the course of two weeks, I bought amazing books and journals from vendors local to Egypt and coming from around the Middle East, met new suppliers of key research materials, and I was able to connect with dear colleagues new and old.

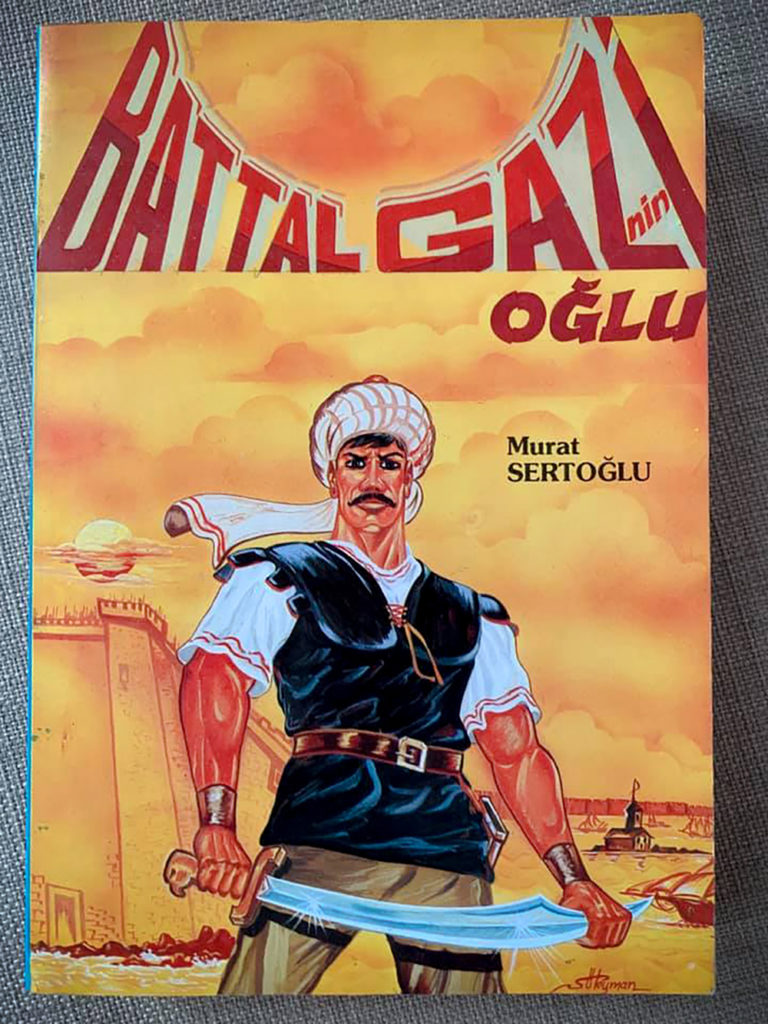

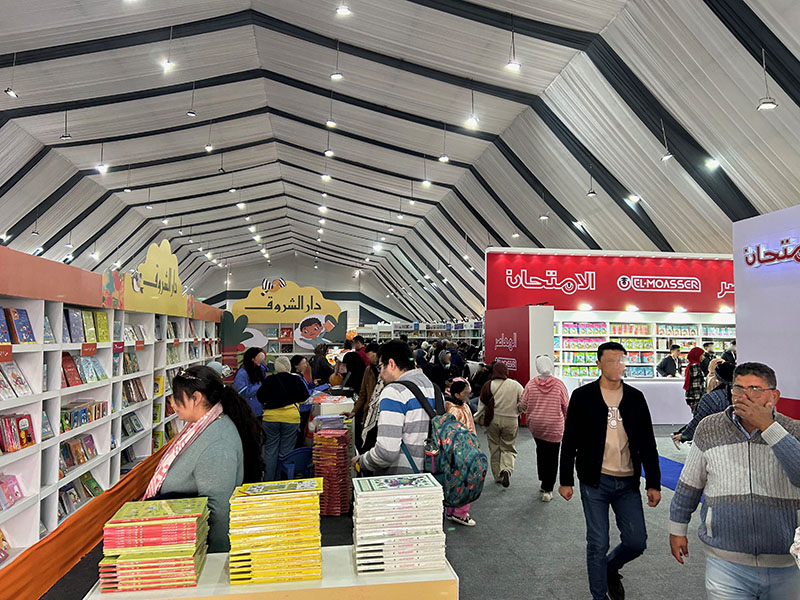

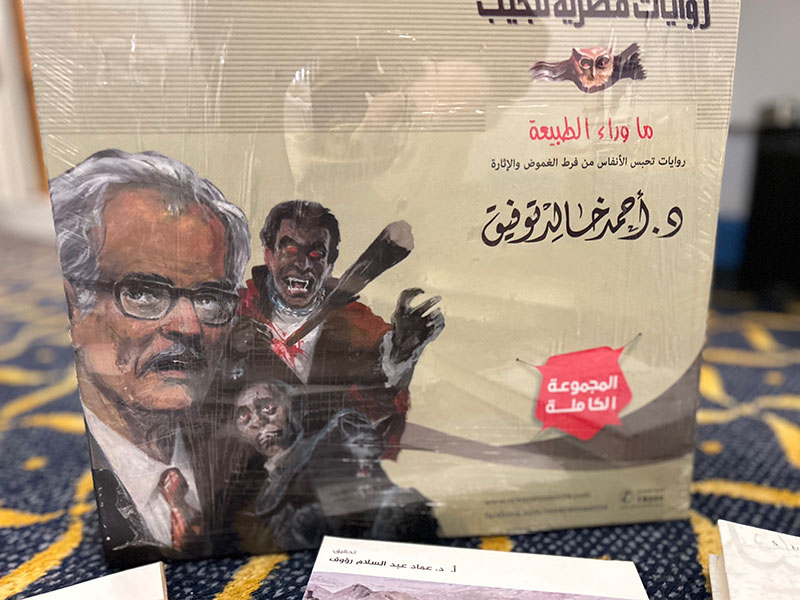

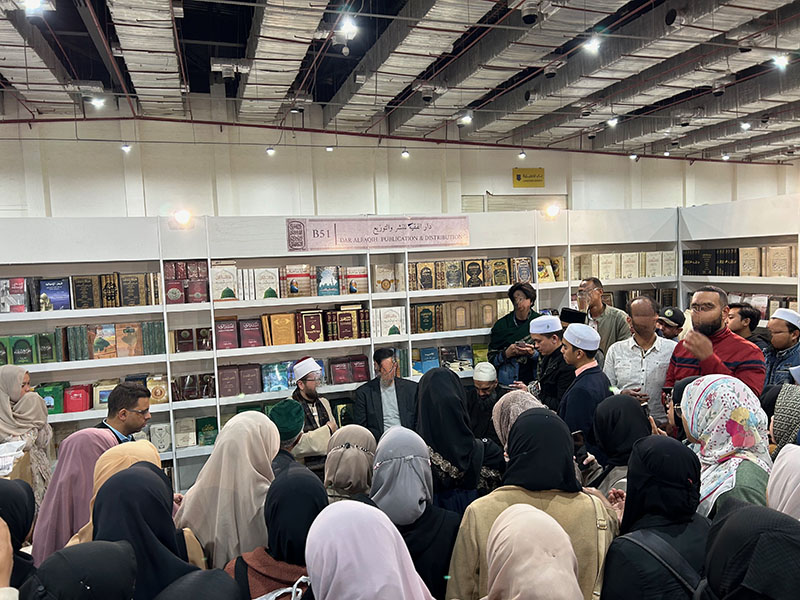

The Cairo Book Fair is massive. This is not hyperbole: the event is often said to be the largest book fair in the world after Frankfurt, and perhaps more family-friendly than any other. Vendors from all over the world come to offer their wares, and people from all walks of life attend. There are groups of Egyptian schoolchildren on field trips; international students studying at Egyptian universities; scholars of the Middle East from around the world; whole families; teens out for a fun afternoon; and of course, librarians from all over the world who come to find the best, most interesting, rare, or latest publications. I spent my first few days at the Cairo Book Fair at the Children’s Hall and making a preliminary review of the international Islamic vendors in halls 3 and 4. It was in the Children’s Hall that I found the publisher al-Mu’assasah al-‘Arabiyyah al-Hadithah li’l-Tab’ wa’l-Nashr, and they were promoting riwayat al-jib, or pocket novels. In particular, they had produced a boxed set of the full supernatural collection of author Ahmad Khalid Tawfiq. UT Austin already owns a few of his works, including, among others, Mithl Ikarus (Just Like Icarus). The set that I bought includes 81 science fiction, fantasy, and paranormal titles in a small, portable format, with––frankly––delicious cover art. This set, titled Ma Wara’ al-Tab’iah, was the basis of the Netflix series Paranormal.

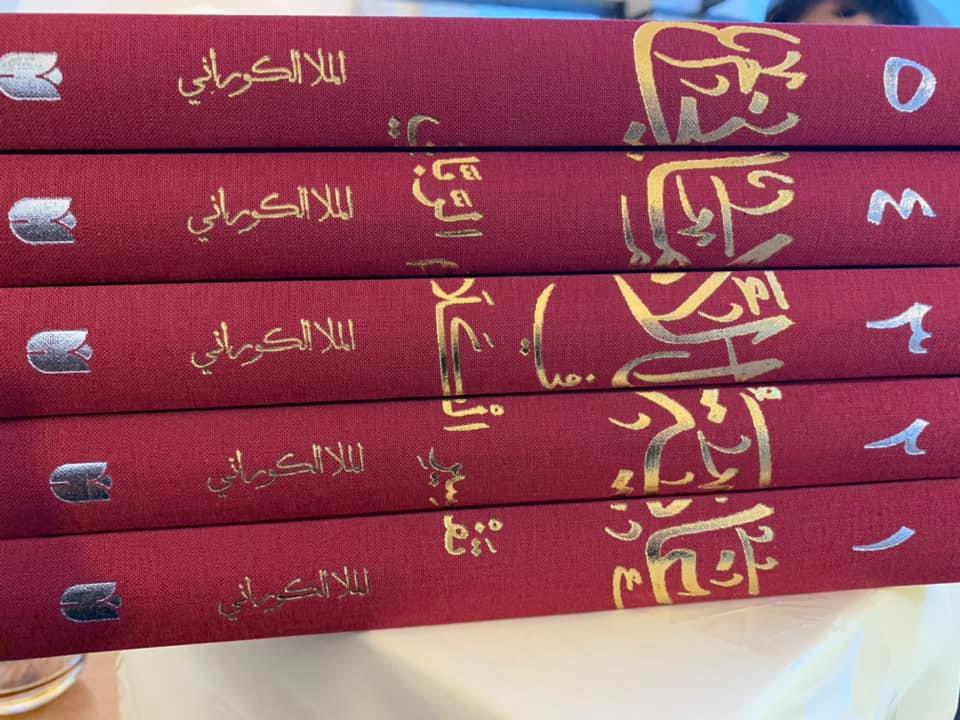

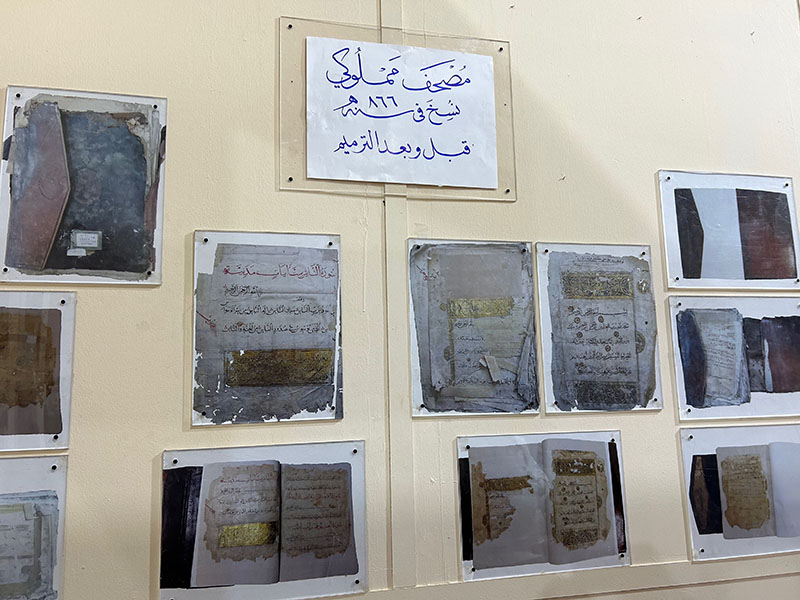

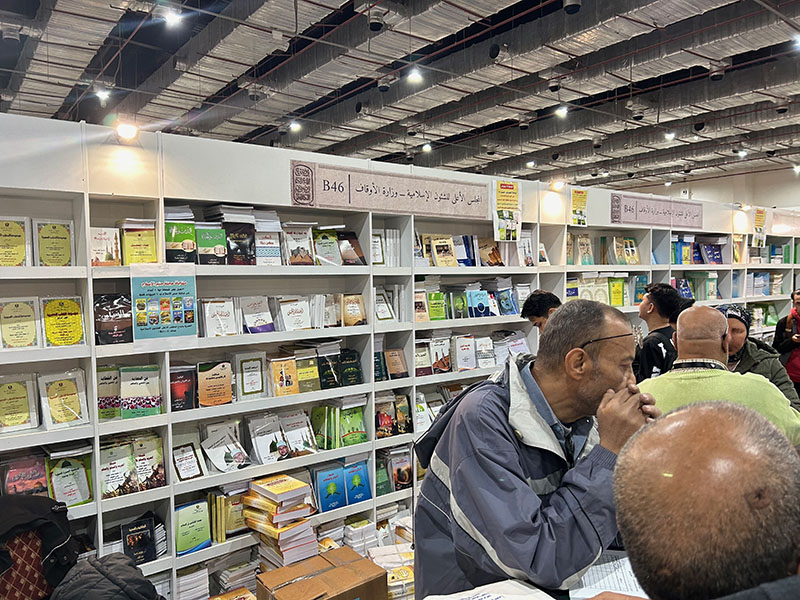

In Halls 3 and 4, I found the majority of the international and Egyptian Islamic vendors. Of particular interest were the booths and pavilions for the Dar al-Ifta’ organization and Al-Azhar University. The latter had an entire pavilion with exhibits on the manuscripts held at the Al-Azhar Library and the expertise of the preservationists who care for those rare and special materials, as well as art displays and activities for children and adults. I took a peek in their storage room to find what I had originally expected and hoped to find: the classic paperback Azhari texts and textbooks. Researchers focusing on the history of Al-Azhar as an educational institution, or on the history of Islamic education at all levels (for al-Azhar is not just a university, but also operates a K-12 school system), would find these materials central to their work. They are inherently ephemeral, due to their purpose of use and construction, so it was a rare opportunity to find them for UT Libraries’ collection.

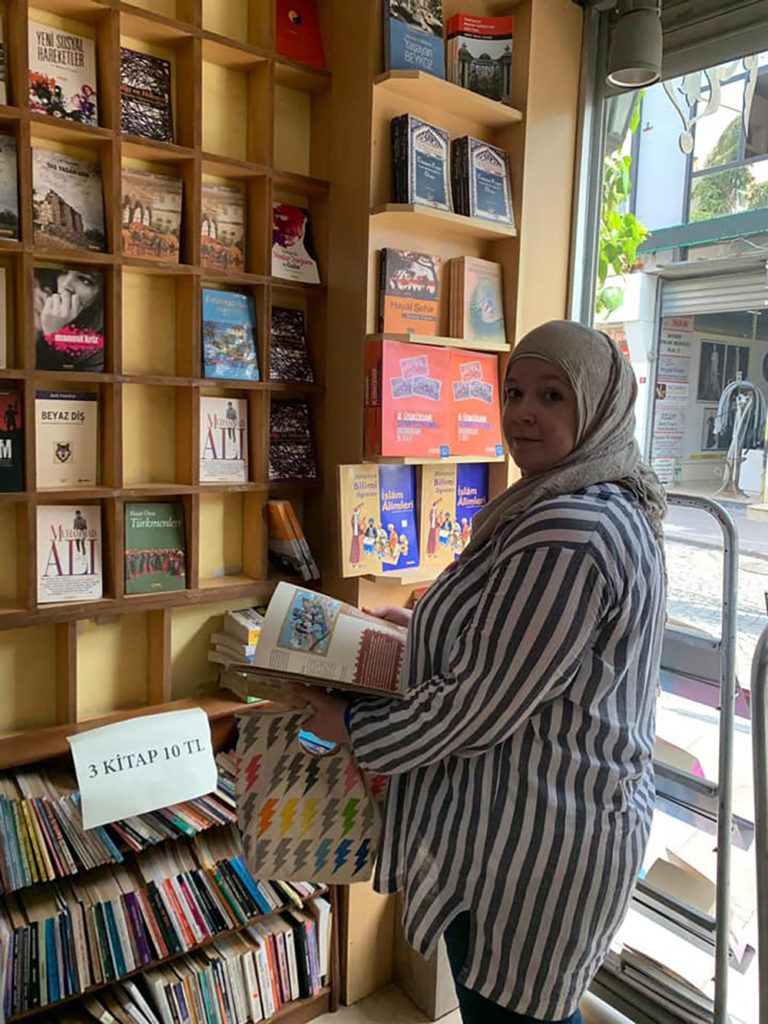

Over the following few days, I made my way with more intention through halls 3 and 4 and also explored halls 1 and 2. I had the pleasure of visiting with fellow librarian, Dr. Walid Ghali, who is a professor and director of the library at the Aga Khan University (London). Dr. Ghali recently released three novels of his own, and we had a delightful conversation about librarianship and authorship while at the booth for his novels’ publisher, Dar al-Nasim. I also had the opportunity to speak with Ashraf ‘Uways, the founder of Dar al-Nasim. It was wonderful to learn more about his approach to selecting titles for publication, and especially his interest in supporting the publication of Arabic novels by authors in non-Arabic speaking countries in Africa. With such wonderful publishers at my disposal, I was acquiring quite a bit of incredible material. Each day, I arrived at the fair with a suitcase to fill, and I wasn’t the only one. From students to families to scholars, nearly everyone had a bag or cart of some kind to help them transport home their precious finds.

Traveling to Egypt was also an opportunity to meet with UT Austin’s regular book vendors. I had the pleasure to see George Fawzy, the director of our beloved vendor Leila Books. We were able to check-in in person about the research priorities at UT Austin and how those shape the materials that we acquire through Leila Books, and we were able to catch up on the state of libraries in North America and publishing in the Middle East. Visiting the Leila Books office is a delight for me because I get to see their incredible work in action, meeting the folks behind acquiring and shipping our materials. I always have to get a photo with the latest UT Austin shipment, and sure enough we had several boxes that were about to be sent out.

Additionally, I was able to meet with a new vendor who specializes in rare materials and visit his warehouse on the outskirts of Cairo. It is from this vendor that I have been able to acquire unique periodicals, including al-Majmu’ah al-Da’imah and al-Majallah al-Misriyyah li’l-‘Ulum al-Siyasiyyah (the Egyptian Journal of Social Science), which I brought back from this trip. Al-Majmu’ah al-Da’imah is a huge, multi-volume work that compiles the official record of judicial decisions issued in Egypt since the beginning of the national court system in 1883, and I would not have been able to locate it without this vendor’s help and some luck. I also found out-of-print significant, even rare, materials from the book market of Azbakiyyah in central Cairo. With the Cairo Book Fair on, the entirety of Azbakiyyah market moves to the Fair, where they have their own dedicated section. The Azbakiyyah booths are the most popular and most lively of the Fair, with materials moving in and out constantly. If you ever want to find a particular scholarly edition, or affordable novels, Azbakiyyah, or perhaps its section at the fair!, is the place to go.

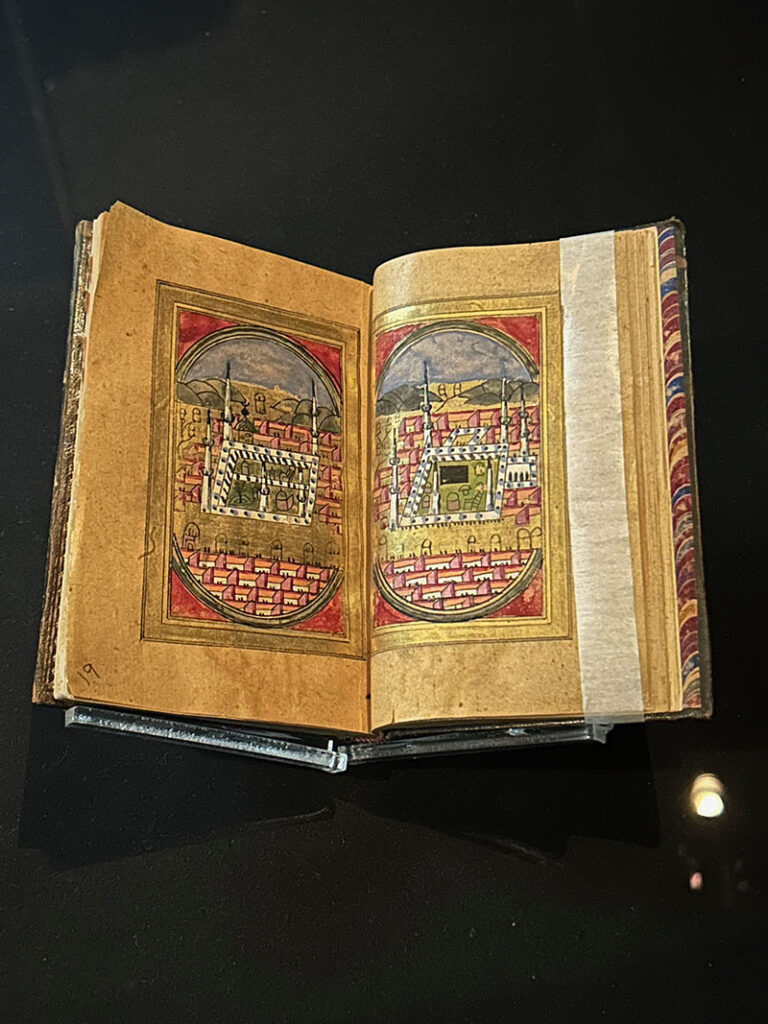

My trip to Egypt was not only about acquiring pivotal materials for the UT libraries—I also took the time to visit key Egyptian cultural heritage institutions and to meet with scholars. I had the honor of finally meeting Dr. Nesrine Badawi (the American University in Cairo) in person. We had an engaging conversation about current trends in Egyptian scholarship and discussed her most recent research on Islamic law and the regulation of armed conflict. Additionally, I was able to visit Alexandria, the second largest city in Egypt, and spend a day at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Although I have visited this beautiful library and its extraordinary collections before, it is always worth a trip for the new exhibits and rotation of special collections on display. On this visit, I was able to tour the reconstructed private library of renowned journalist and director of al-Ahram newspaper, Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. The extensive exhibit was a stunning look inside Heikal’s education, career, and personal and professional relationships. For my own intellectual amusement, I spent a great deal of time in the rare books room, reviewing the latest rotation of centuries-old manuscripts. Bibliotheca Alexandrina now boasts a significant collection of ancient Egyptian art and contemporary Egyptian art, ranging from paintings to sculpture to ceramics.

It was a delight and an honor to be able to return to Egypt and to visit the Cairo Book Fair this year. I am sincerely grateful to the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, the UT Libraries, and our generous HornRaiser donors for making this trip possible. I look forward to my next trip and the caretakers and creators with whom I will forge relationships.