Leading up to the opening of the Learning Commons, we’ve spoken in broad terms about the impact of having a suite of student resources and services co-located for ease of access and use, and how that convenience is expected to improve student outcomes. Much of the talk regarding that impact of the Learning Commons has centered on the process and completion of finished products of a more temporal nature such as reports, projects and other assignments, but beyond the resources — technical help, knowledge resources and technology — that will serve as the basis for user productivity, it’s worth considering the persisting influence that the learning opportunities supported by the new space will provide to the next generation of Longhorns.

Staff in the Libraries’ Teaching and Learning Services (TLS) unit has played a central role in planning the Learning Commons, and their activities will have a significant impact on the success of the initiative. The longstanding relationship between TLS and the University Writing Center was essential to the relocation of UWC to the Perry-Castañeda Library, and much of the vitality in the Learning Commons will be determined by how the partnership between the two groups evolves over time. UWC’s nascent presence has already reaped ideas for collaborating with the Libraries on programming in the new space, and coordinating with other student resources around campus — such as the Sanger Learning Center — will allow a crossover between the provisional service needs of users for the purpose of completing assignments and the generation of lasting skills like interviewing, public speaking, information literacy, and much more.

Staff in the Libraries’ Teaching and Learning Services (TLS) unit has played a central role in planning the Learning Commons, and their activities will have a significant impact on the success of the initiative. The longstanding relationship between TLS and the University Writing Center was essential to the relocation of UWC to the Perry-Castañeda Library, and much of the vitality in the Learning Commons will be determined by how the partnership between the two groups evolves over time. UWC’s nascent presence has already reaped ideas for collaborating with the Libraries on programming in the new space, and coordinating with other student resources around campus — such as the Sanger Learning Center — will allow a crossover between the provisional service needs of users for the purpose of completing assignments and the generation of lasting skills like interviewing, public speaking, information literacy, and much more.

TLS emerged in 2002 — at the time designated Library Instruction Services — to take the place of the Digital Information Literacy Office (DILO) and expand on its mission to integrate information literacy into the campus-wide curriculum for general education, which it successfully accomplished in 2010. The unit’s name evolved to Teaching and Learning Services as its mission has expanded to represent a more comprehensive view of the academic landscape and the ways in which students and faculty interact to share knowledge and experience.

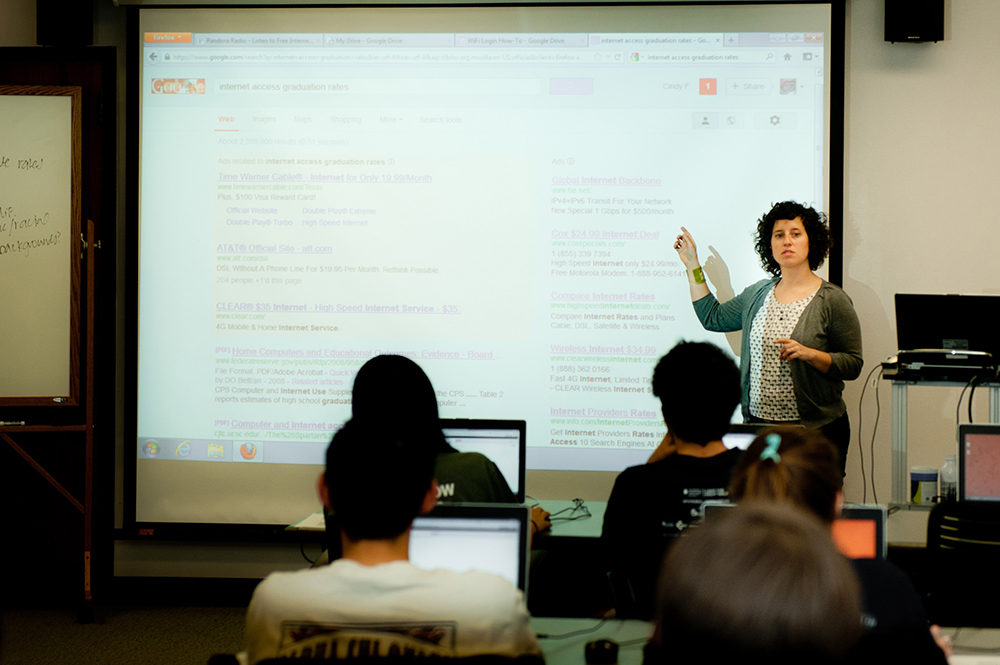

By its increased involvement in campus curriculum via information and digital literacy, TLS has routinely collaborated with faculty on assignment design and presents course-integrated classes in hands-on classrooms in the libraries. They’ve also created video tutorials on subjects such as avoiding plagiarism for integration into course web sites and embedding in online courses. Through a combination of these methods, TLS now reaches almost 3,000 lower division undergraduates every year.

“The Learning Commons isn’t just about co-locating academic support services for ease of access but is about collaborating in new ways across those departmental lines to better support teaching and learning,” says Michele Ostrow, head of the Libraries’ Teaching and Learning Services unit. “We’re fortunate to work closely with a lot of fantastic faculty who teach in our freshmen programs and are committed to helping the excellent high school students who get into UT become excellent college students.” Continue reading Commons Learning

“The Learning Commons isn’t just about co-locating academic support services for ease of access but is about collaborating in new ways across those departmental lines to better support teaching and learning,” says Michele Ostrow, head of the Libraries’ Teaching and Learning Services unit. “We’re fortunate to work closely with a lot of fantastic faculty who teach in our freshmen programs and are committed to helping the excellent high school students who get into UT become excellent college students.” Continue reading Commons Learning