Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from UTL’s Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

Financially supported by the Indian Ministry of Culture, the Virtual Museum of Images and Sound is an online platform drawing upon and digitally presenting the amazingly rich resources held in the American Institute of Indian Studies’ (AIIS) collections. While the open access museum highlights a vast range of artistic expression that I encourage everyone to explore, this brief post highlights the audio recordings from the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE).

Grab your headphones, settle into your comfortable chair, and join in to listen and learn!

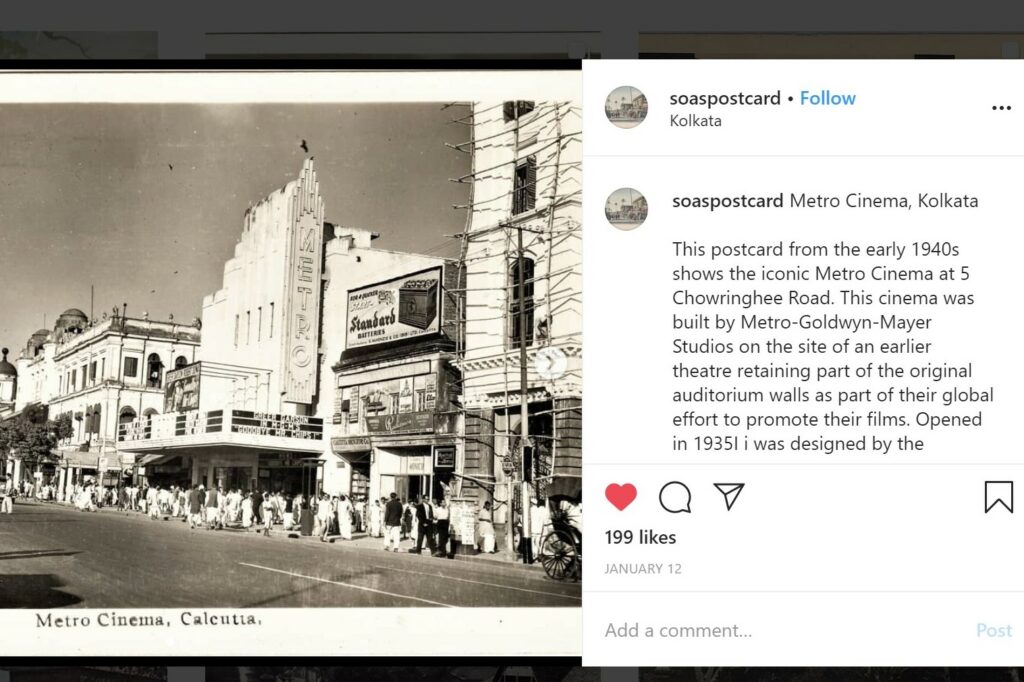

For those new to South Asian music traditions, the ARCE’s Music in Context section provides a great introductory overview as it organizes recordings thematically. While one might expect a section on ragas, the ARCE site encourages one to listen to songs associated with life cycle events, with work, or with ritual traditions. If curated thematic journeys aren’t your style, rest assured that the site also operationalizes a number of digital humanities methods to delve into the dizzying array of musical types. For example, one can use the Mapping Music or the Music Timeline interfaces to discover recordings by geographical location or in their chronological context. There are so many fascinating things to find here—for example, did you know that the American jazz artist Teddy Weatherford lived in Kolkata (the city then known as Calcutta) and was featured on India’s First Jazz Record in 1944? Or that the 1978 “Jazz Yatra” brought the likes of saxophonist Sonny Rollins and sitarist Ustad Vilayat Khan together? One loses oneself in the midst of such resources.

Beyond the fun to be had on the site from wherever you are, it is important to remember ARCE’s compelling vision to support the study of ethnomusicology in India. The original goals for the AIIS analog collection were to protect and preserve recordings made by foreign scholars in the course of their research which were subsequently deposited in archives around the world. Troublingly, it was obvious that such recordings were rarely available in India itself. Addressing this problem head on, ARCE declares that “repatriation of collections has remained a major aim of the ARCE, which houses collections… which were not [previously] available in India. Scholars and collectors from all over the world, as well as India, continue to deposit collections of their recordings regularly at ARCE.” In addition, they see the collection and the wide array of associated programs and events anchored in the collection as a way to stimulate new ethnomusicological research worldwide. Knowing this driving mission, it is no surprise that ARCE has made so many collections freely available online. I commend them on this important work.

I further applaud ARCE on their partnerships to collaboratively digitize and make recordings openly available. To cite one recent and impactful success, ARCE worked with grant funding from the Modern Endangered Archives Program (MEAP) to preserve, robustly describe, and offer access to the “Recordings of Hereditary Musicians of Western Rajasthan.” A scholarly collection formerly only on audio cassettes, the new online open access through ARCE and MEAP allows listeners worldwide to celebrate and enjoy Rajasthani music, culture and history.

Learn more with these databases (restricted to UT affiliates):

Saarey Music provides streaming access to over 60 years of South Asian classical music including genres like Dhurpad, Thumri, Kafi, Tarana, and Ghazal.

Smithsonian Global Sound is a virtual encyclopedia of the world’s musical and aural traditions and includes material from the Archive Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE).

Ethnomusicology: Global Field Recordings presents content from across the globe, including thousands of audio field recordings.

Music Online: Listening provides access to over 7 million streaming audio tracks, see in particular the “World Music” section.