Leer en español | Ler em português

It was the Summer of Zoom. Anyone whose job quickly morphed from being in-person to being entirely online can relate to (a) isolation, (b) feeling overwhelmed, (c) video-conference overload, or (d) some or all of the above. Yet the ability to engage with other people on platforms such as Zoom has allowed some important work to move forward. Such was the case with the recent workshop series conducted with archival partners in Latin America by the LLILAS Benson Digital Initiatives team (LBDI).

The workshops were originally planned to occur in person during a week-long retreat in Antigua, Guatemala, with a group of Latin American partner archives. As an essential activity of the two-year Mellon Foundation grant titled Cultivating a Latin American Post-Custodial Archiving Community, the week would provide an opportunity for partners from Guatemala, El Salvador, Colombia, and Brazil to come together for training, share resources and knowledge, exchange ideas, and discuss challenges they face in their work.

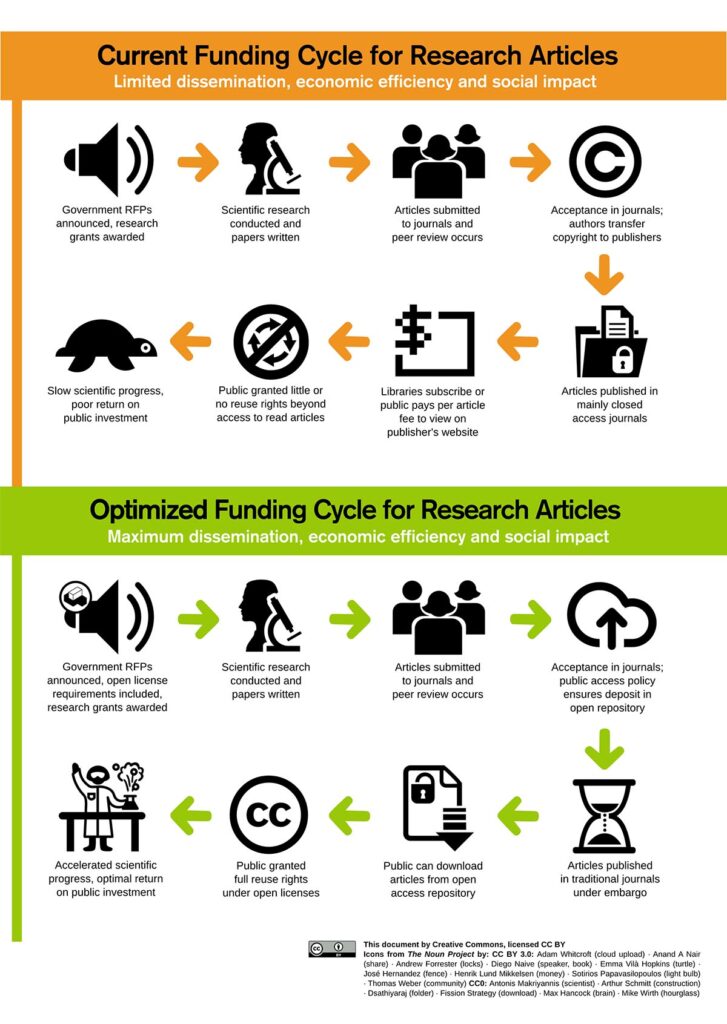

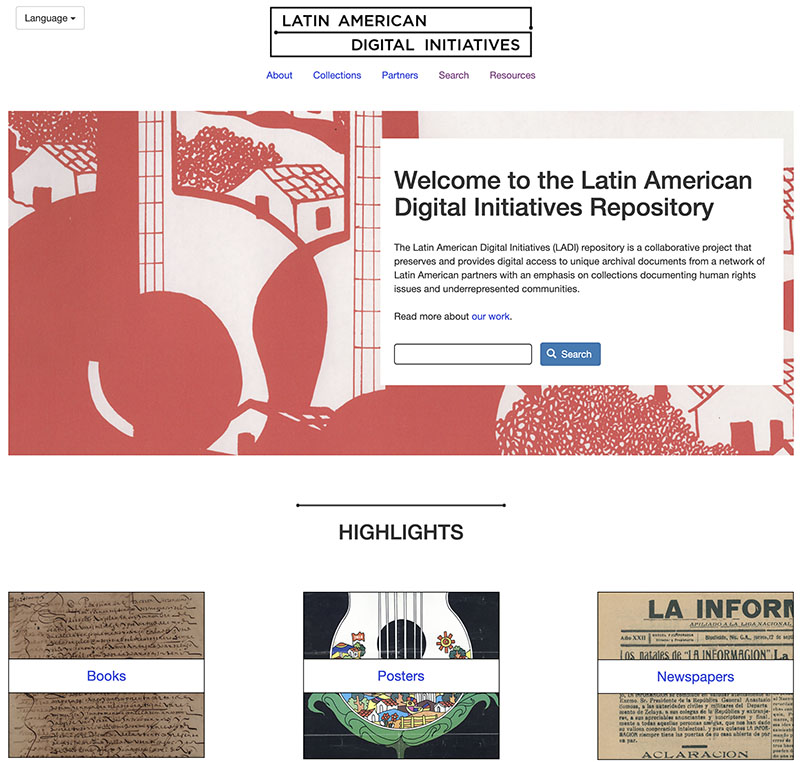

The Mellon grant, covering work between January 2020 and June 2022, provides funding to support post-custodial* archival work with five partner archives, some of whom are already represented in the Latin American Digital Initiatives repository, which emphasizes collections documenting human rights issues and underrepresented communities.

The Covid-19 pandemic demanded that the digital initiatives team quickly pivot in order to keep the project moving forward on the grant timeline. For the resulting workshop series, offered via Zoom, members of the LBDI team prepared extensive training videos, designed Q&A sessions, and arranged for sessions with guest experts. Topics included grant writing, budgeting, archival processing, metadata, equipment selection, digital preservation, and digital scholarship, among others.

Over the course of five weeks this past summer, workshop participants met twice a week with LBDI staff members Theresa Polk, David Bliss, Itza Carbajal, Albert Palacios, and Karla Roig, as well as LLILAS Benson grants manager Megan Scarborough. All sessions were conducted in Spanish with closed-caption translations into Portuguese (or vice versa) provided by Susanna Sharpe, the LLILAS Benson communications coordinator. Additional presenters included Carla Alvarez, the U.S. Latinx archivist at the Benson Latin American Collection, and photo preservation experts Diana Díaz (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and María Estibaliz Guzmán (Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía, ENCRyM, Mexico).

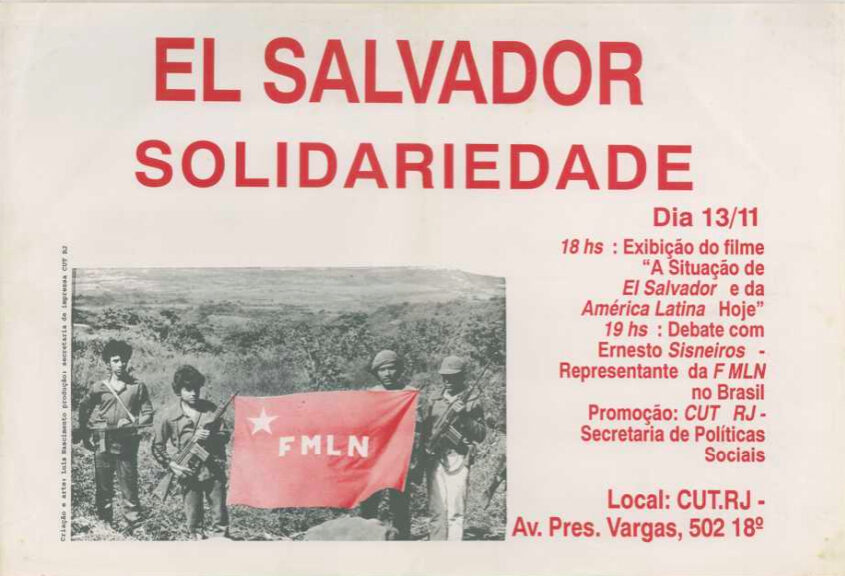

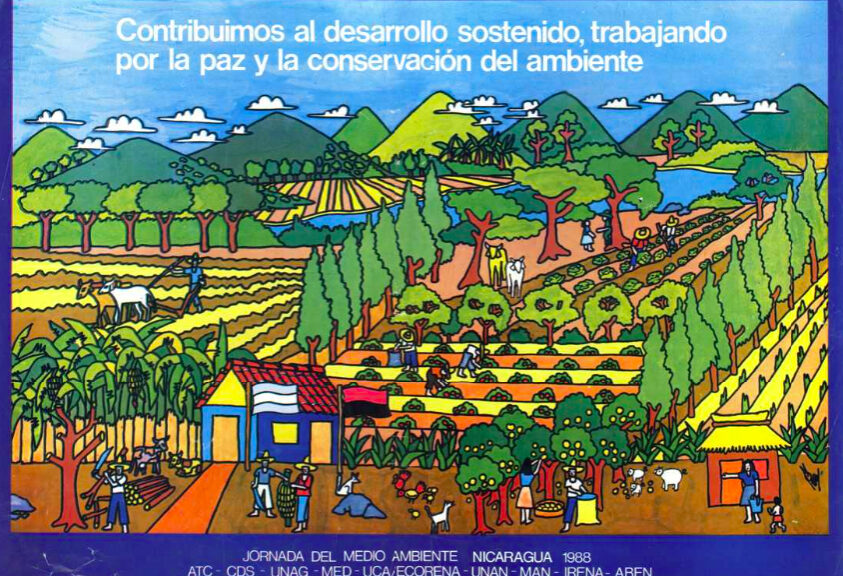

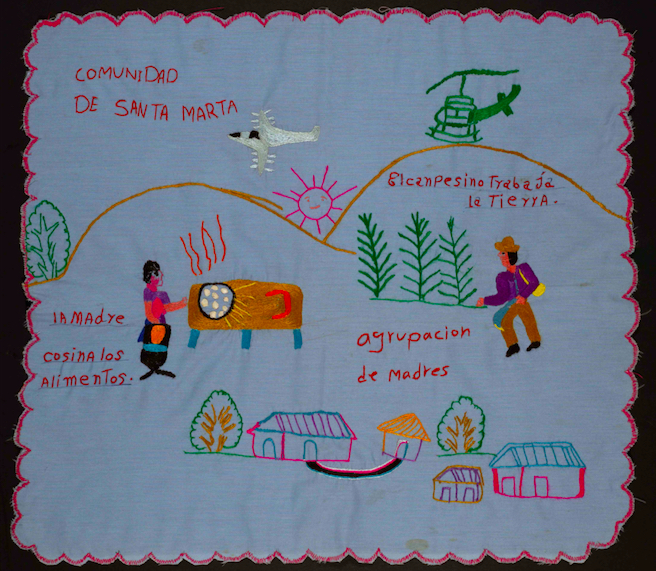

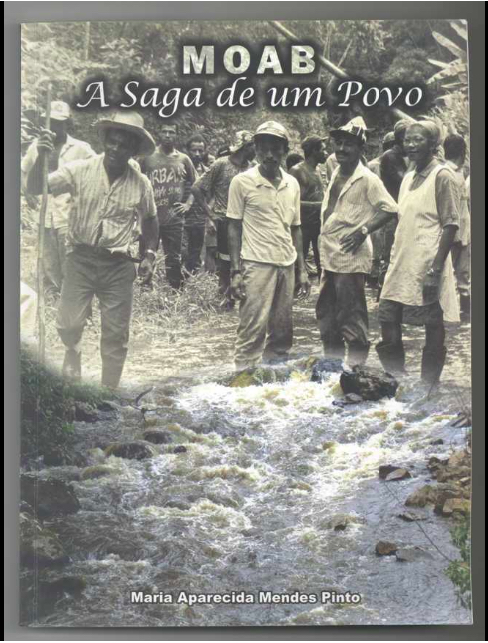

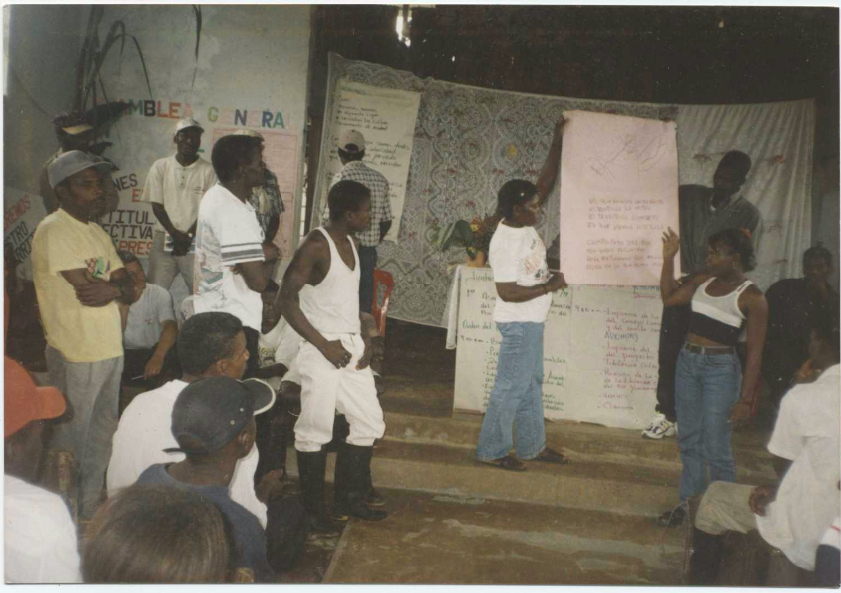

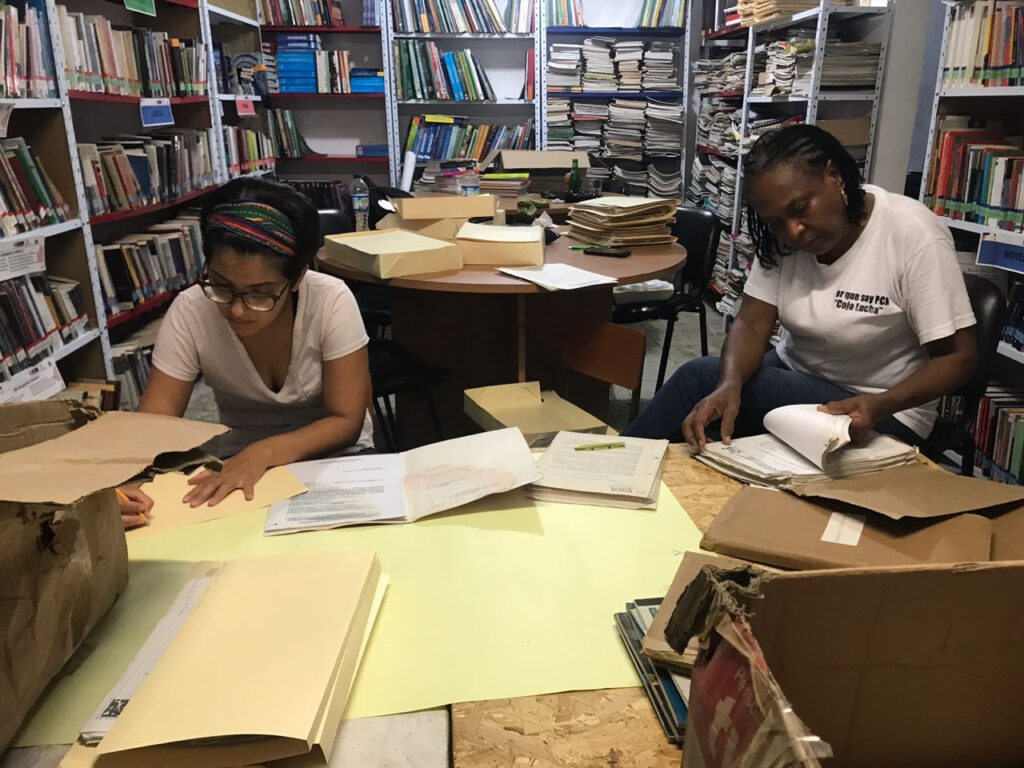

Partner archives who were able to participate in the online workshop series included Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen (San Salvador, El Salvador), Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala (ODHAG, Guatemala City, Guatemala), Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN, Buenaventura, Colombia), and Equipe de Articulação e Assessoria às Comunidades Negras do Vale do Ribeira (EAACONE, Vale do Ribeira, Brazil).

Despite the physical distance, workshop participants clearly valued the opportunity to come together and learn from one another, especially during the pandemic, which has had such profound effects on daily life as well as work. The increased isolation, repression, and attacks against communities that have accompanied the pandemic also underscored for partners the urgency of preserving their communities’ documentation to support current struggles for recognition and respect of basic human rights, and to prevent future efforts to erase or deny ongoing violence and injustice. This shared commitment fostered a sense of solidarity and mutual support among participants.

“For our team, it was an enriching experience that allowed us to reflect, as part of a multinational group, on the achievements and expectations of the LLILAS Benson Mellon project,” reported Carlos Henríquez Consalvi (aka Santiago) of MUPI, who also remarked on the opportunity to get to know the work of partner archives, “and to learn of their challenges with conservation and diffusion of their respective collections.”

Carolina Rendón, one of two participants from ODHAG’s Centro de la Memoria Monseñor Juan Gerardi, expressed how the day-to-day burdens of the pandemic were lightened by the opportunity to meet with others: “It was very good to be in spaces with others who work in different archives across Latin America. The pandemic has been heavy. During the course of the workshops, we passed through several stages—lockdown, fear, horror at the deaths, . . . . I appreciate getting to know, even virtually, people who work in archives in other countries.”

For the LLILAS Benson team, the positive comments, and the general feeling of gratitude for the solidarity of online gatherings, offset the heavy lifting of preparing multiple training videos per week in Spanish, with texts quickly and expertly translated to Portuguese by collaborator Tereza Braga. In words of David A. Bliss, digital processing archivist, “The biggest challenge was distilling a huge amount of technical information down to its most important elements and communicating these as clearly as possible in Spanish.”

Bliss also alluded to the fact that the partners themselves are a diverse group with different backgrounds, needs, and types of archives: “Some of our partners have been running digitization programs for years, but for others the information was all new, so I worked hard to strike a balance between the two using visual aids and clear definitions for technical terms.”

One of the most rewarding aspects of the workshop series was knowing that archivists and activists who work to preserve important records of memory in the area of human rights were able to come together, albeit virtually, to share their work and their perspectives with one another. As Bliss put it, “Ordinarily, we work individually with each partner organization to help them manage their digitization project, with the goal of gathering all of their collections together in LADI. But many of our partners don’t just hold collections of historical documents; they’re engaged in ongoing struggles for their communities. They’re far more equipped to help one another strategize and succeed in that work than we are, so giving them the space to form those direct connections with one another is really important. It’s also very validating for us, because it’s been one of our goals for years now: we want to be just one part of a network of partners, not at the center of it.”

* Post-custodial archiving is a process whereby sometimes vulnerable archives are preserved digitally and the digital versions made accessible worldwide, thus increasing access to the materials while ensuring they remain in the custody and care of their community of origin. LLILAS Benson is a pioneer in this practice.