Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this new series, librarians from UTL’s Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

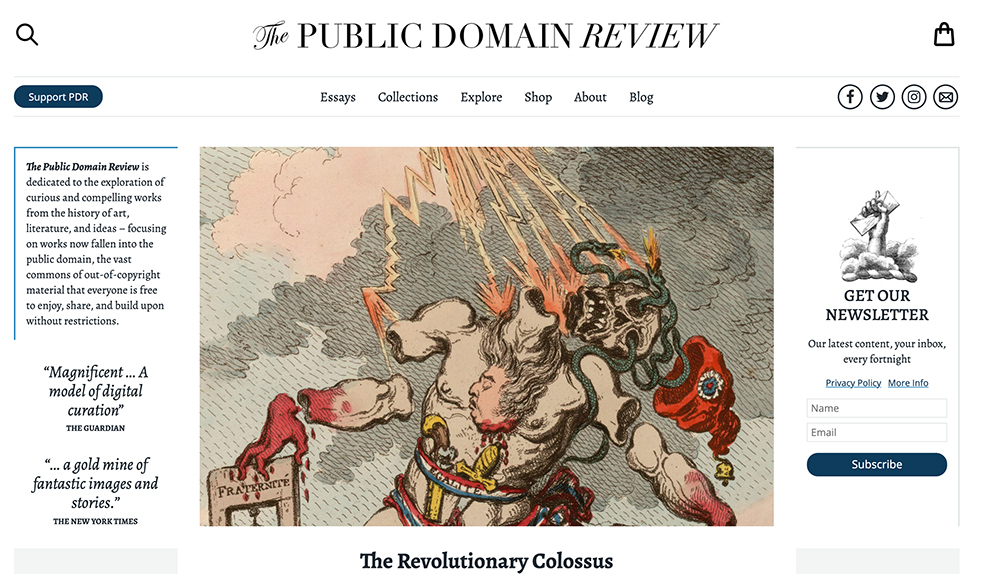

As we enter a more digital workspace, the copyright of content we reuse in presentations or projects has become a more pressing question in our public facing work. While there are ways to search for resources by their Creative Commons licenses or by digging through the public domain, the results are not always satisfying. Enter The Public Domain Review, an online journal of scholarly essays and curated collections of material from the public domain.

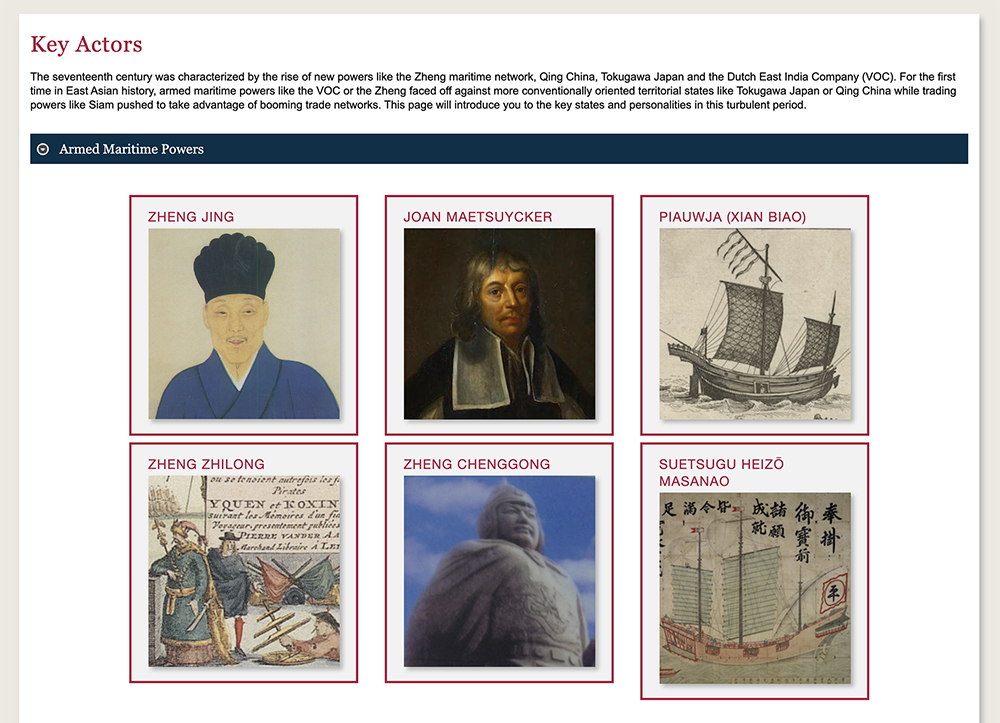

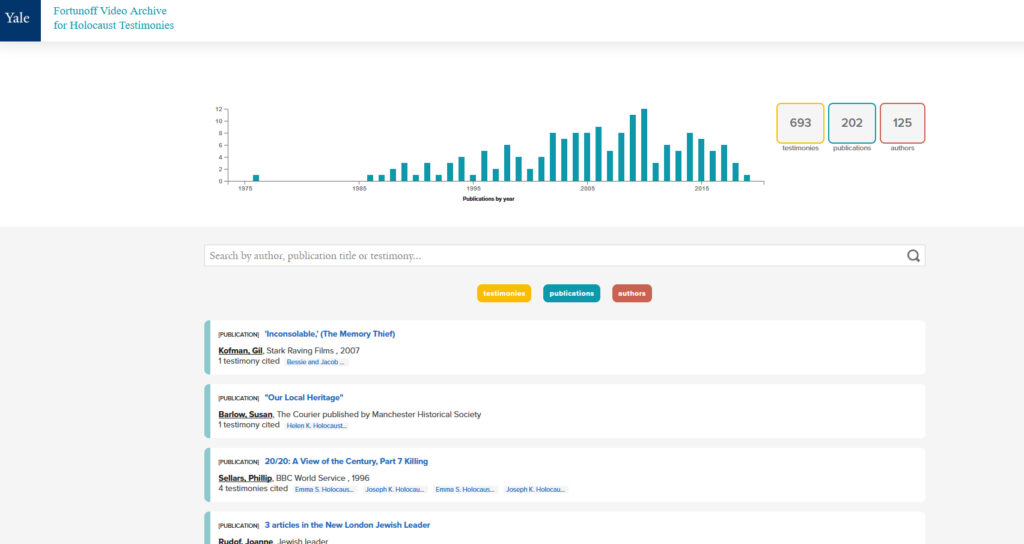

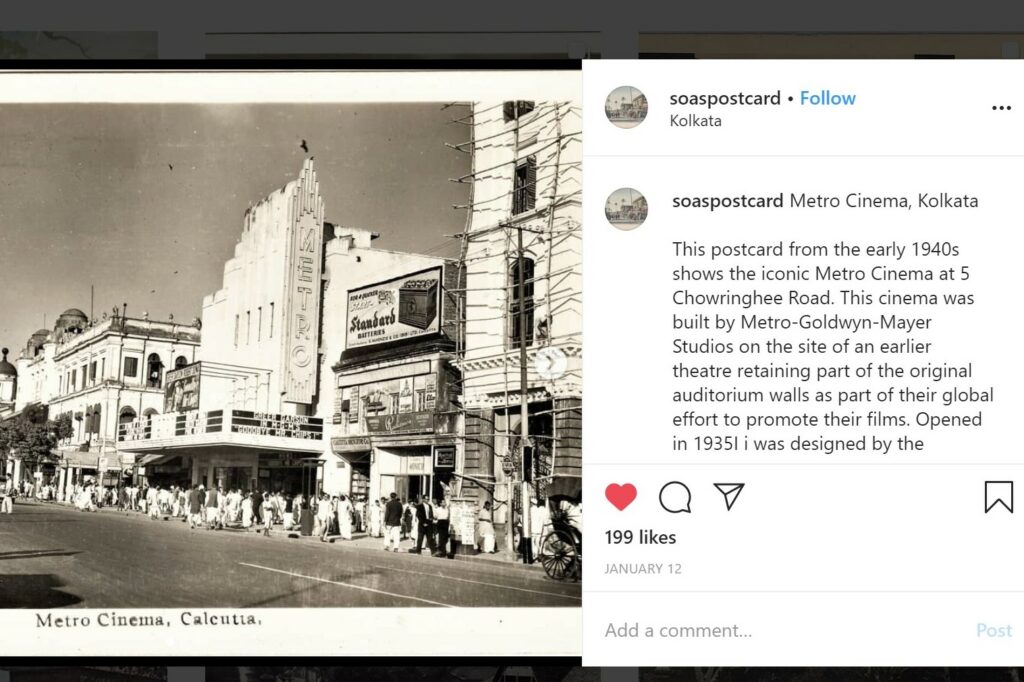

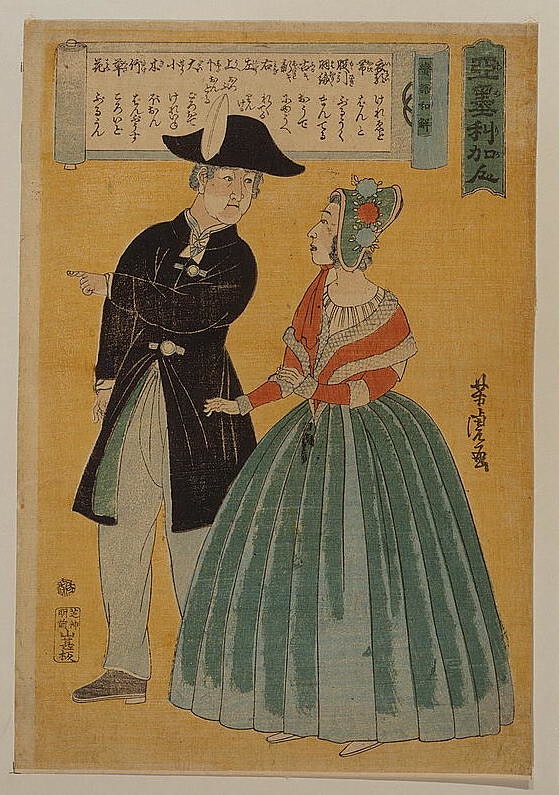

The public domain refers to creative content in the United States that is no longer protected under copyright law. Every January 1st, works published before a certain year are released from copyright protection. 2021 welcomed material published in 1925 into the public domain. The first day of 2021 also saw The Public Domain Review celebrate its 10th anniversary of curating and publicizing interesting and obscured content from the public domain, related to history, art and literature. The digitized items and collections are gathered from 134 cultural heritage institutions and platforms across the internet, including the Smithsonian, Wikimedia and the Library of Congress. What separates The Public Domain Review from just another list of curious findings on the internet is the academic commentary on the relics by scholars, archivists and creatives in its Essays section. The collections on the site are mostly western-centric with a few global works included and are organized by theme, time period and medium. The pieces featured in the Review are not just images but also include film, books and audio. The level of organization and tagging make the unique compilations and essays easy to delve into on the site through its Explore page.

The project was developed ten years ago by history scholars and archives enthusiasts Adam Green and Jonathan Grey. The goal of The Public Domain Review has been to inform and highlight relics often forgotten or buried so deep that it would be difficult to come across serendipitously. The projects’ keen eye for the intriguing, supplemented by its expert commentary are what keeps me coming back to the site, either through the Review’s monthly mailing list or when I need an image for a presentation. The project’s editorial board selects collections and welcomes contributors to submit proposals that feature hidden cultural heritage materials.

The Public Domain Review is teeming with potential for digital scholarship endeavors and while there is no active portion of the project engaging with those scholarly methods, there are traces. The project site itself was built by UT Austin graduate, Brian Jones, a historian and web developer. In the retired series, Curator’s Choice, a guest writer from the GLAM sector (galleries, libraries, archives, museums), would spotlight digital collections or digital scholarship projects from their own institutions. See notable digital humanist, Miriam Posner on anatomical filmmaking here and read how scholars at The British Library are using digital technology to recreate a medieval Italian illuminated manuscript from fragments here.

The site also encourages reuse and remixing through its PD Remix section, holding caption competitions or gif creation challenges using works from their public domain highlights. Although a not-for-profit, they do have a Shop, selling prints, mugs, bound collections of Selected Essays, with the profits used to keep the lights on in this scholastic and engaging corner of the internet.

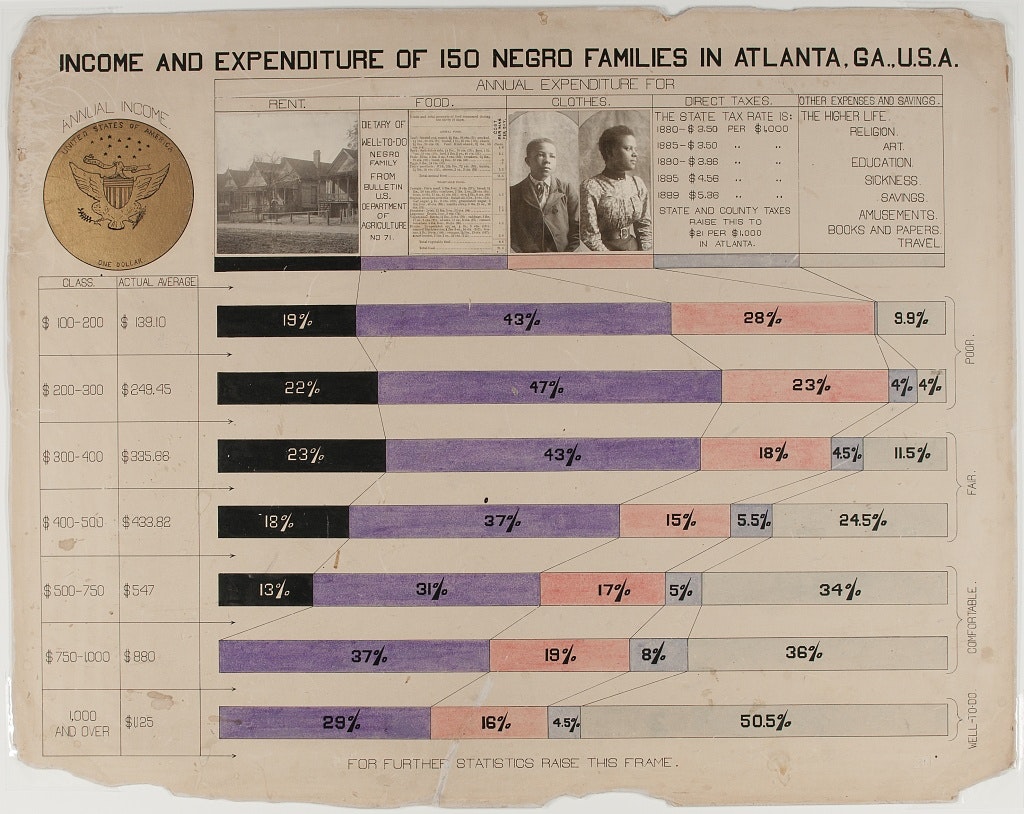

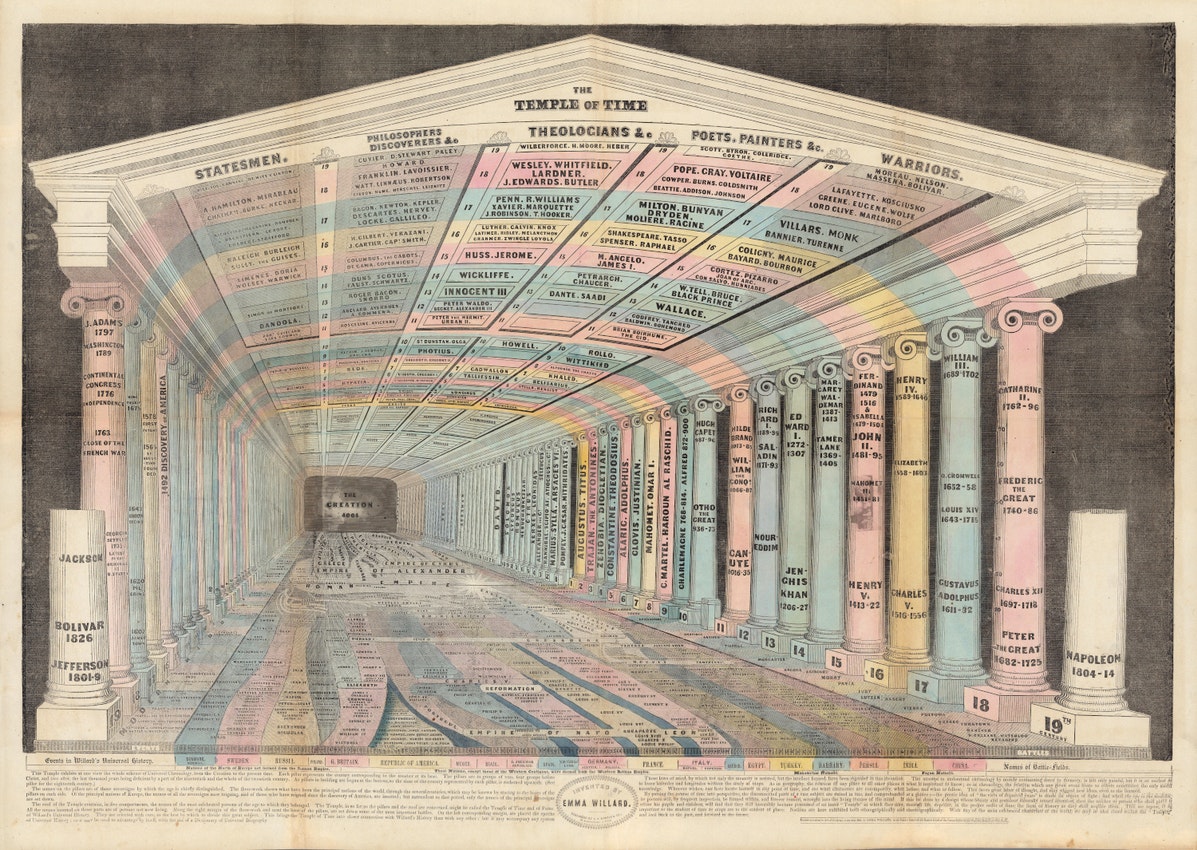

The public domain itself is a treasure trove of cultural artefacts often hidden by the complexities and rules in copyright law. Luckily, The Public Domain Review exists to spotlight these relics and even shows you how to find your own out-of-copyright gems. Below are some of my favorite exhibits and essays from The Public Domain Review.

Find out more about the public domain in UT Libraries collections and guides:

-Still not sure what the public domain is or want to know more about copyright and fair use? See the library’s Copyright Crash Course guide.

-Take a look at the list of works that entered the public domain in 2021 on UT Austin’s Open Access blog here.

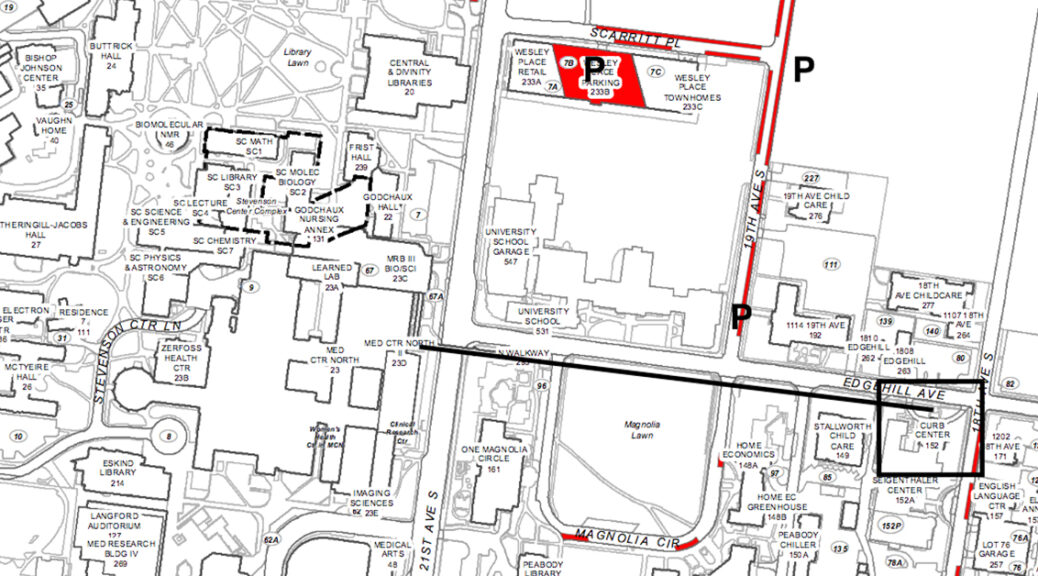

-Fire insurance has never been more exciting than when depicted in the colorful, aesthetically pleasing Sanborn Fire Maps from the PCL Map Collection.