Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from UTL’s Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship.

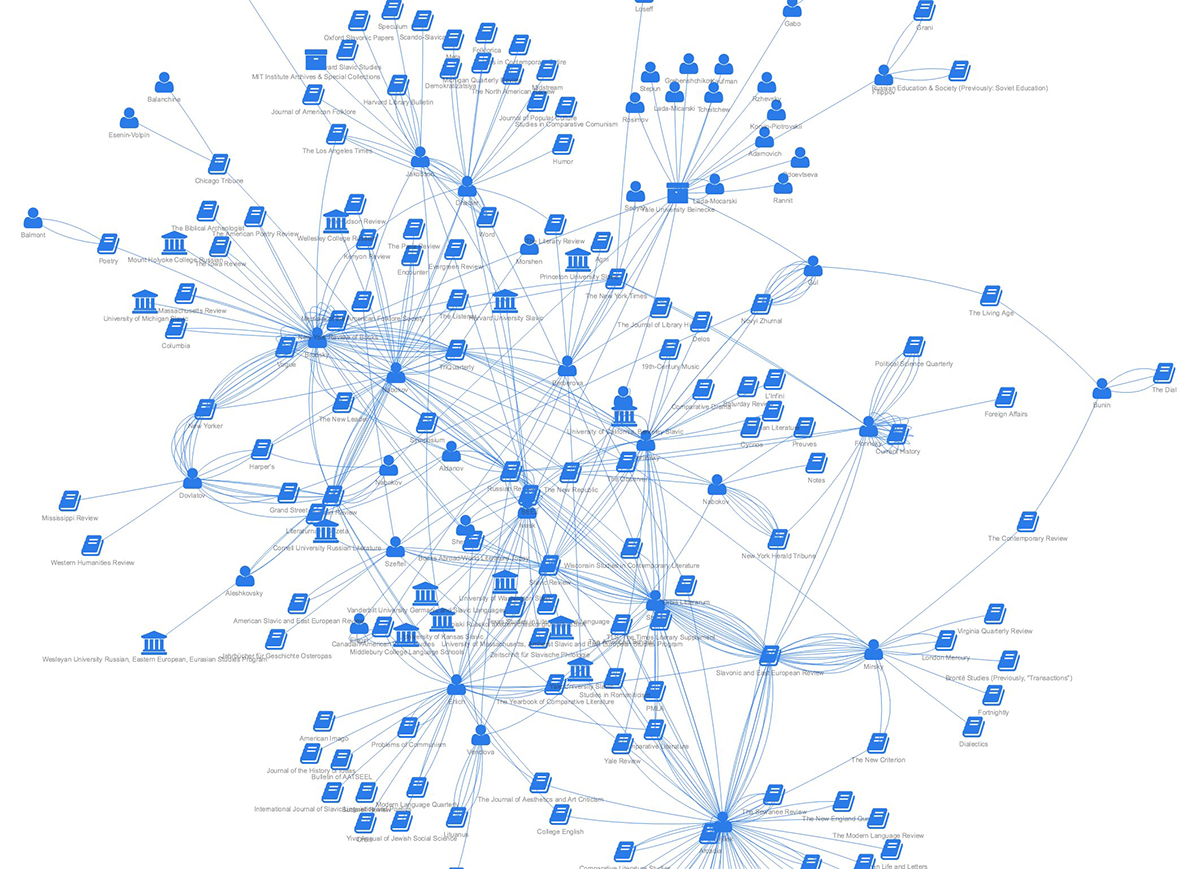

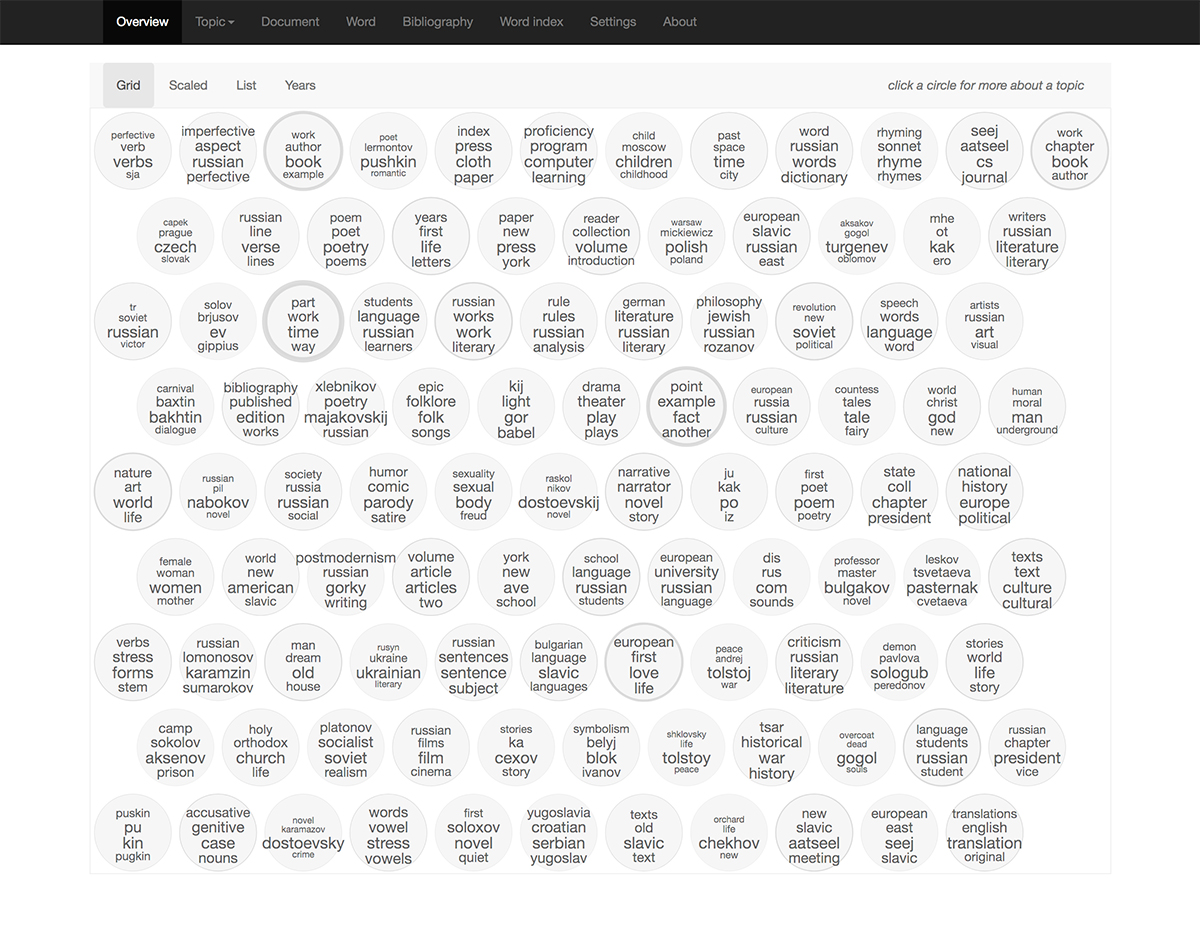

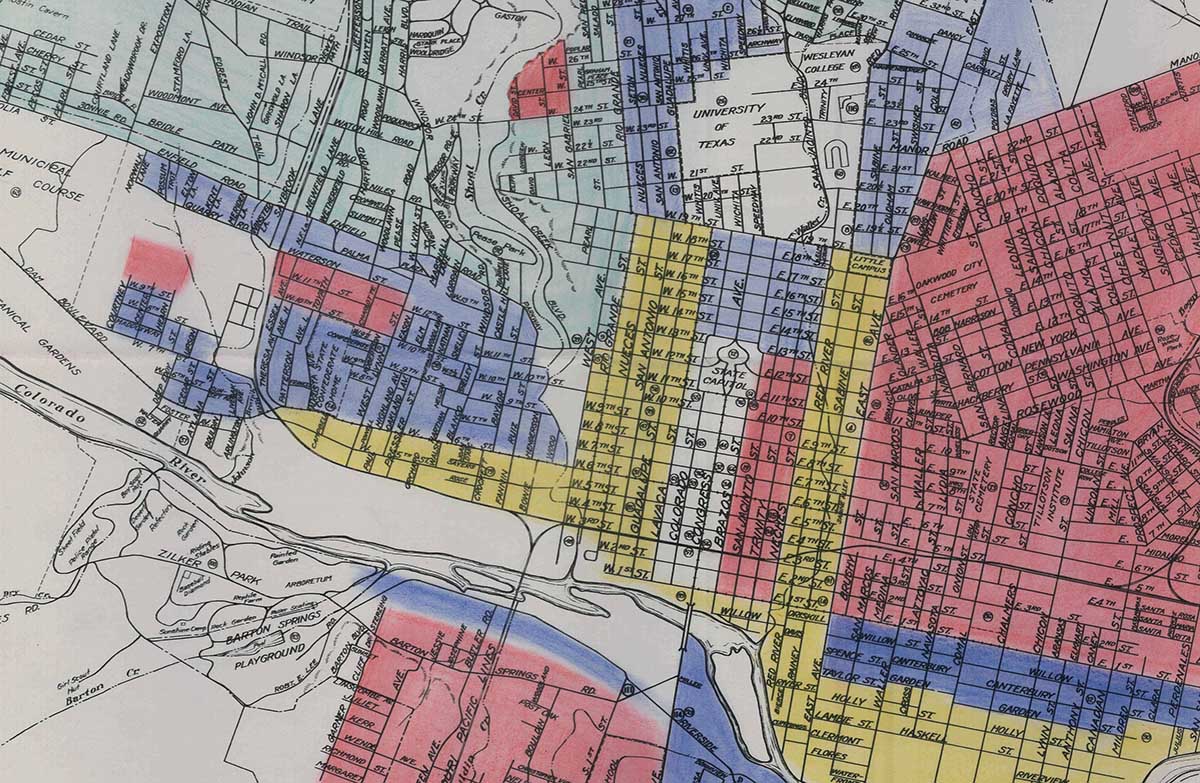

When speaking of digital humanities and the field of art history, cautioners of “digital art history” argue that using digital tools is useful only if those tools facilitate an actual rethinking about an object as to its identity and purpose.[1] Certainly, applying quantitative digital methods to an art history project sometime fails to hit the mark for one reason or another. For example, network diagramming, first used with text-based DH projects, does not always successfully transfer to the study of the visual. See the map created in 2013 for the entry to MOMA’s “Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925”, which has been criticized for not providing much insight into the events surrounding the rise of Abstraction (https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/inventingabstraction/?page=connections). Or in another case, the wonderfully ambitious 2012 project “Mapping Gothic France” (http://mappinggothic.org/) that was originally financially supported by the Mellon Foundation, now languishes because of lack of funding and the untimely death of one of the project’s two creators.

However, successful digital humanities/art history efforts are happening; one being “The Oplontis Project” (www.oplontisproject.org) impressively initiated 14 years ago, in 2005, here at UT Austin by faculty members, Dr. John Clarke and Dr. Michael Thomas.

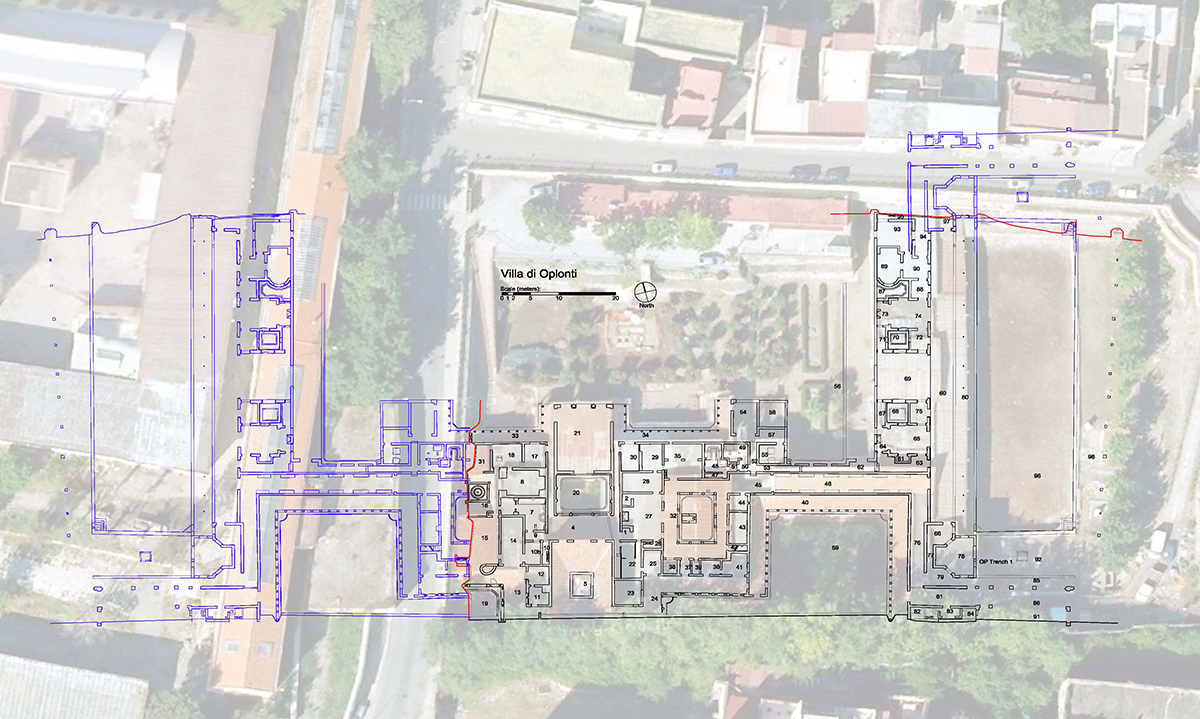

This is a mind-bogglingly large project involving numerous specialists’ studies of a villa (Villa A) and a commercial complex at Oplontis, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Torre Annunziata, near Pompeii.

Still going strong, this project involves a growing database for sharing; a website, promoted through Facebook to reach a wider audience (https://www.facebook.com/pg/TheOplontisProject/photos/?tab=album&album_id=335748659810305); and eventually, 4 volumes of born digital, open access, e-books devoted to the Oplontis Villa A. The 1st volume of this e-book series, on the ancient setting and modern rediscovery of the villa, was published in 2014 (See https://catalog.lib.utexas.edu/record=b8986409~S29). The 2nd volume, which traces the decorations, stucco, pavements and sculpture, will appear this spring 2019. This second volume, alone, contains 2700 high resolution images, a feat that could never be realized in print format. In addition, the e-book format allows for quick links to other material like excavation notebooks.

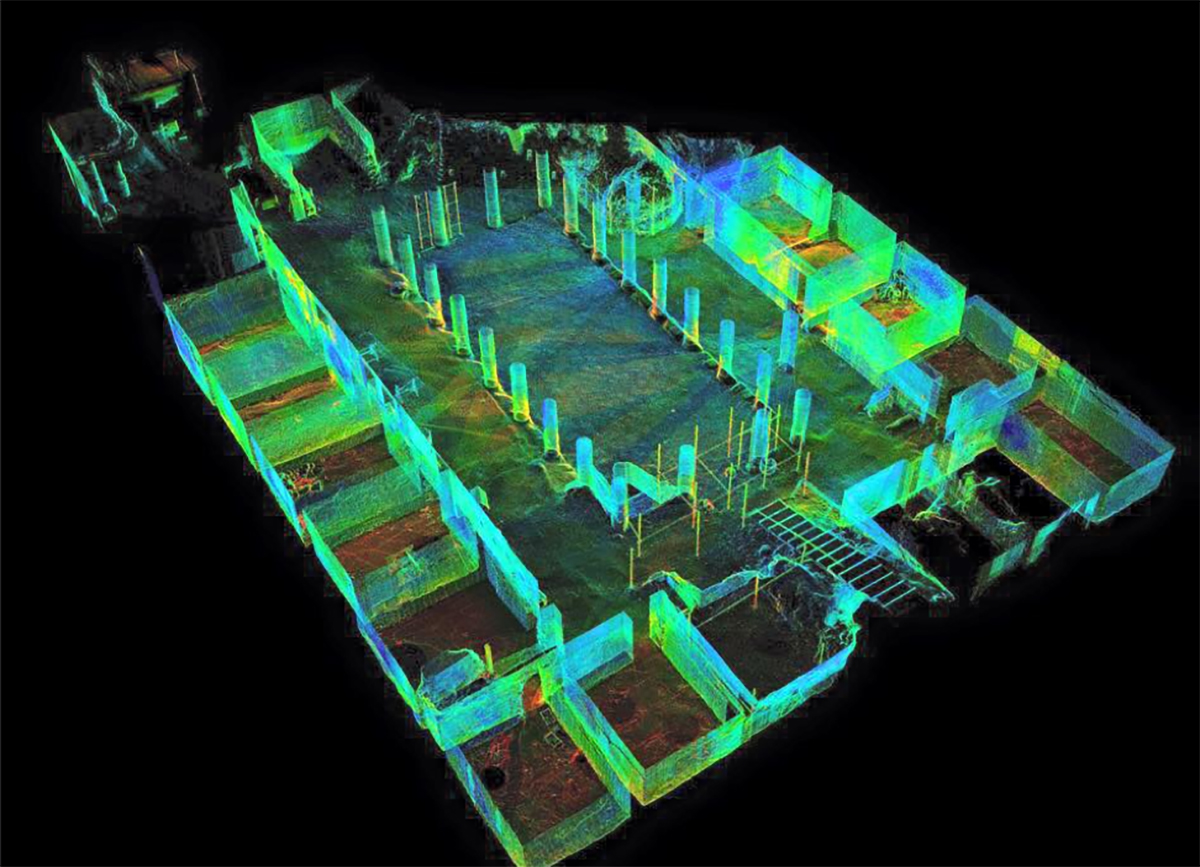

With the help, among others, of UT’s own Texas Advanced Computer Systems (TAC) (https://www.tacc.utexas.edu/special-report/corral/archeology), members use digital photography and 3-D laser scanning and modeling of wall paintings, mosaics, and sculpture to layer what exists today with digital visualizations that allow the modern viewer to navigate through the rooms as if they were guests in the original villa. In addition, the site’s gardens were replanted based on pollen and seed analyses; and marble fragments have yielded information about ancient trade routes.

I think the success of this digital humanities project can be attributed to several factors. Notably, questions about chronology, function, social structure and landscape that have guided the research at this site, were posited from the very beginning. The huge team of involved specialists firmly grasp how to use digital and scientific tools in the service of research questions for the purpose of yielding new ways of looking at this site and it material culture. Ongoing funding has also been crucial. And finally, there is the way in which this DH project’s findings have been and will continue to be disseminated. As John Clarke says, “The 3D model, linked with the database will allow us, and future generations, to find material easily by clicking on find-spots; scholars will be able to share in our work and even add to the information in our database. The model complements the e-book and because the ACLS[2] has graciously offered to make the Oplontis Project publications open access, scholars and laypersons worldwide can benefit from the work of our 42 contributors, coming from a wide range of scientific and humanistic disciplines.”[3]

For more information about Oplontis and other surrounding sites see:

Leisure and luxury in the age of Nero : the villas of Oplontis near Pompeii, 2016, https://catalog.lib.utexas.edu/record=b9138737~S29

“The Villa of Oplontis”, in Preserving complex digital objects, 2014, https://catalog.lib.utexas.edu/record=b8960178~S29

Tales from an eruption : Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis : guide to the exhibition, 2003, https://catalog.lib.utexas.edu/record=b5889687~S29

The natural history of Pompeii, 2002, https://catalog.lib.utexas.edu/record=b5389520~S29

[1] See Johanna Drucker, Is There a “Digital” Art History , Visual Resources, v. 2

[2] The American Council of Learned Societies Humanities E-book series is the publisher of The Oplontis E-book volumes

[3] See the John Clark interview https://notevenpast.org/new-digital-technologies-bring-ancient-roman-villa-to-life/