Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the UT Libraries Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of, and future creative contributions to, the growing fields of digital scholarship.

The Texas Freedom Colonies Project (TFCP) was founded in 2014 by Dr. Andrea Roberts as a multimodal research and social justice initiative to document and preserve Texas’ historic Black settlements. Affiliated with Texas A&M University, the TFCP is a unique digital scholarship project that highlights the resiliency of Black communities in Texas through GIS mapping, archival research and community outreach.

Settlements founded by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War up until the 1930s were known as “Freedom Colonies” in Texas. These rural communities were established by Black Texans as self-sufficient colonies and offered refuge from the treacherous systems of debt bondage and sharecropping in the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. Although 557 Freedom Colonies are known to have existed, the project notes that “Freedom Colony descendants’ lack of access to technical assistance, ecological and economic vulnerability, and invisibility in public records has quickened the disappearance of these historic Texas communities.” [1]

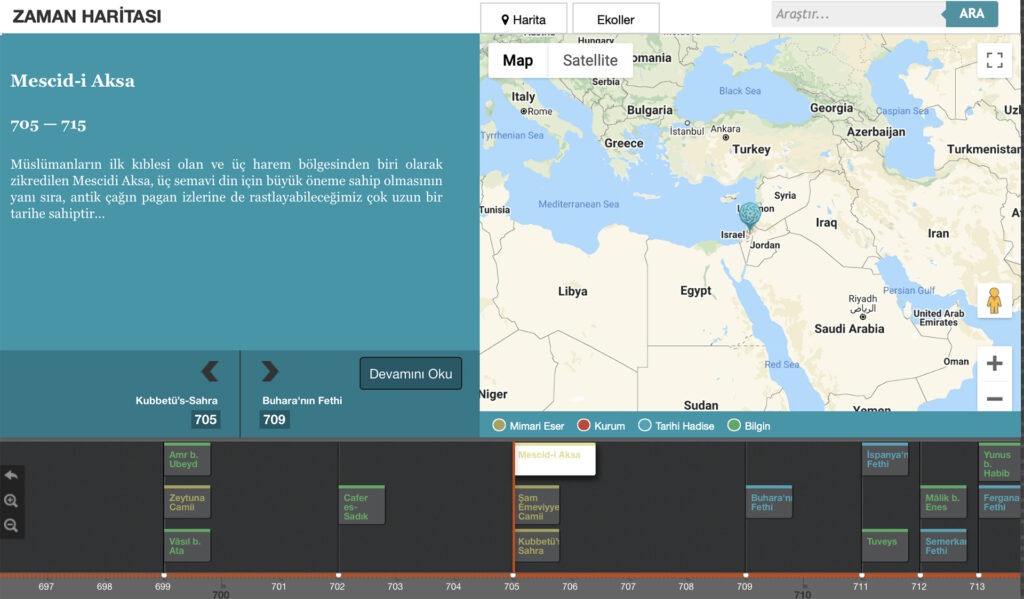

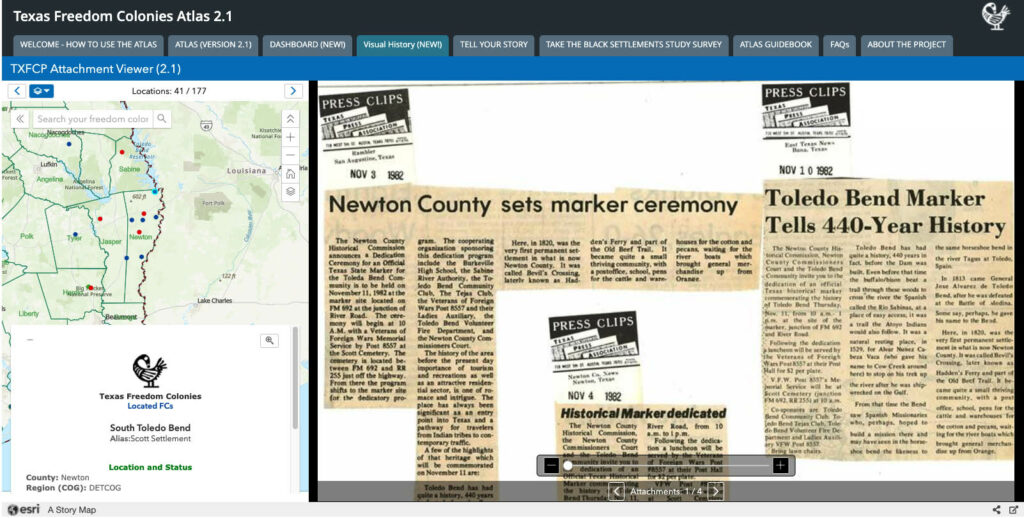

That’s where the Texas Freedom Colonies Project’s Atlas comes in. The project’s interactive map displays Freedom Colonies’ physical locations alongside records of the settlement’s history documented in primary and secondary sources, community websites and other media. So far, the project has mapped the points of 357 colonies in Texas and has documented all known 557 colonies in its Atlas database.

Built with ArcGIS StoryMap, the atlas utilizes dynamic GIS layers to show current development and ecological threats to surviving communities. The project’s use of external datasets as custom map layers distinctly illuminates the power and significance of this digital mapping project by revealing the interconnected history and present of Texas Freedom Colonies.

For example, the “Texas Harvey Affected Counties” layer shows Texas counties that were affected by hurricane Harvey in 2018. The TFCP notes that 64% of Freedom Colonies were located on land that FEMA designated as disaster areas (!). Viewing the Atlas with this particular layer is a striking visual reminder of how vulnerable these communities are as they were often founded on land prone to natural disasters.

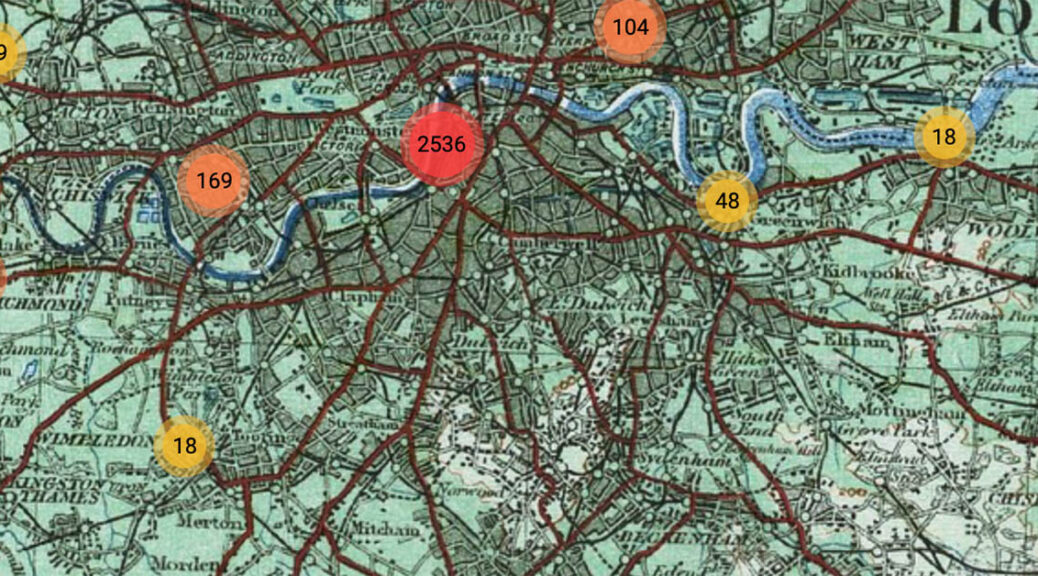

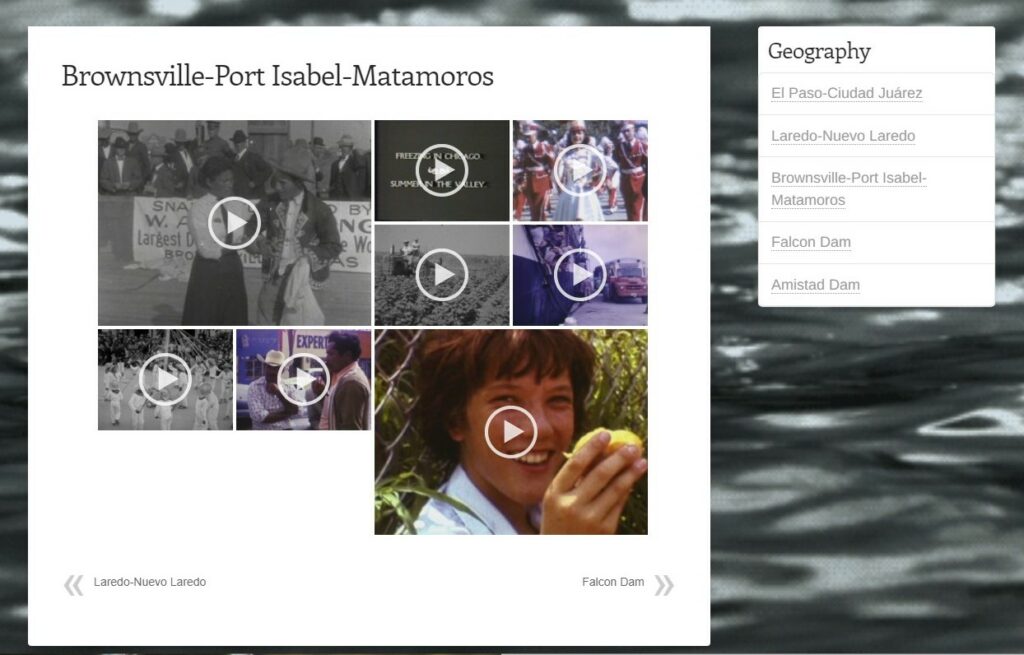

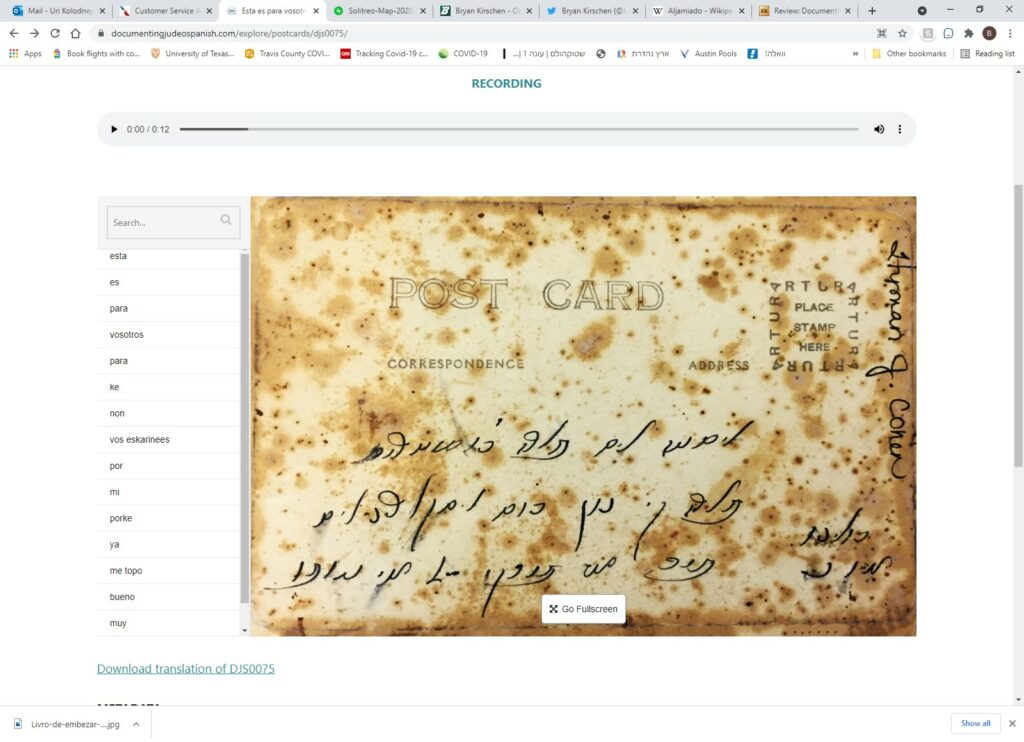

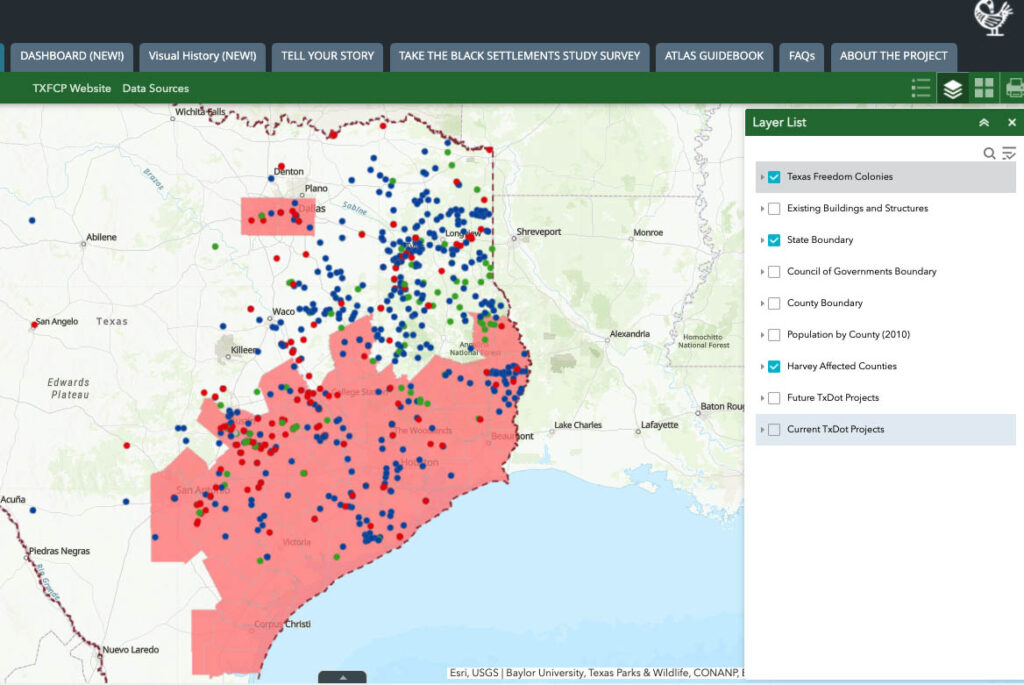

The TFCP is also a testament to the power of grassroot activism, harnessing the knowledge of living communities, descendants and volunteers. One way the public can be active participants in the preservation of Freedom Colonies is through community mapping. “Community mapping” or “participatory mapping,” is an application of critical cartography that emphasizes the importance of community knowledge as markers of place and belonging. Users can submit details of Freedom Colonies like locations and photos of cemeteries, churches and schools through a crowdsourcing form built on ArcGIS Survey123. This documentation helps preserve communities that may not be physically apparent on a map and actively counters presumptions by the state of what history is worth preserving.

![Screenshots of figures showing user contributions to the TFCU Atlas.[2]

Figure 54 shows a screenshot of Camptown Cemetery Polygon put on the map by a user.

Figure 55 shows a screenshot of the pop-up window for Camptown Cemetery showing information, documents, pictures uploaded by a user.](https://texlibris.lib.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Texas-Freedom-ColoniesTEXAS-FREEDOM-COLONIESIMAGE_3.jpg)

The Atlas is an impressive showcase of the combined efforts of volunteers, scholars and living communities to assert the history and resilience of communities that have not often been recognized and financially supported. You may notice that the project logo depicts a Sankofa, a bird frequented in traditional Akan art that symbolizes the importance of reflecting on and reclaiming the past to build a better future. And that is exactly what the Texas Freedom Colonies Project project is doing.

See More

Shankleville Community Oral History Collection

Texas Freedom Colonies: A Bibliography

Interested in volunteering for the Texas Freedom Colonies Project? Click here to learn more about the research community of practice dedicated to locating freedom colonies and information about freedom colonies.

Pruitt, Bernadette. The Other Great Migration: The Movement of Rural African Americans to Houston, 1900-1941. Texas A&M University Press, 2013.

Roberts, Andrea R. “Documenting and Preserving Texas Freedom Colonies.” Texas Heritage 2 (2017): 14–19.

Sitton, Thad, and James H. Conrad. Freedom Colonies : Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow. Jack and Doris Smothers Series in Texas History, Life, and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005.

[1] “What Are Freedom Colonies?,” The Texas Freedom Colonies Project, 2020, https://www.thetexasfreedomcoloniesproject.com/what-are-freedom-colonies.

[2] Biazar, MJ, “Participatory Mapping GIS Tools for Making Hidden Places Visible: A Case Study of the Texas Freedom Colonies Atlas” (Master’s Report, Texas A&M University, 2019), https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/177491/MJBiazar_Masters_Final_Paper_Report.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.