Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the Libraries’ Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship to encourage and inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

Mapping Access is a crowdsourced mapping and data visualization project started at Vanderbilt University through their Critical Design Lab that examines physical and social barriers on the Vanderbilt campus. Professor Aimi Hamraie began the project as a Dean’s Fellowship in 2016 with a small $2500 grant from the National Humanities Alliance and in partnership with the Nashville Feminist Collective. Vanderbilt University Library Fellow Leah Samples was charged with planning and execution of the project. The initial goal was to assess and map the accessibility of spaces around Vanderbilt and Nashville in order to provide necessary information to disabled users for navigating around campus but also more generally to gain insights and to look critically into the accessibility of built environments. The project’s website explains that Mapping Access was informed and influenced by methods and theories from disability justice, the environmental humanities, intersectionality, and critical GIS to look beyond code compliance and satisfying legal standards to create a more human centered approach to accessibility. As such, it exemplifies one of the key principles of the Universal Design movement, namely that features that help disabled users will also yield benefits to non-disabled users.

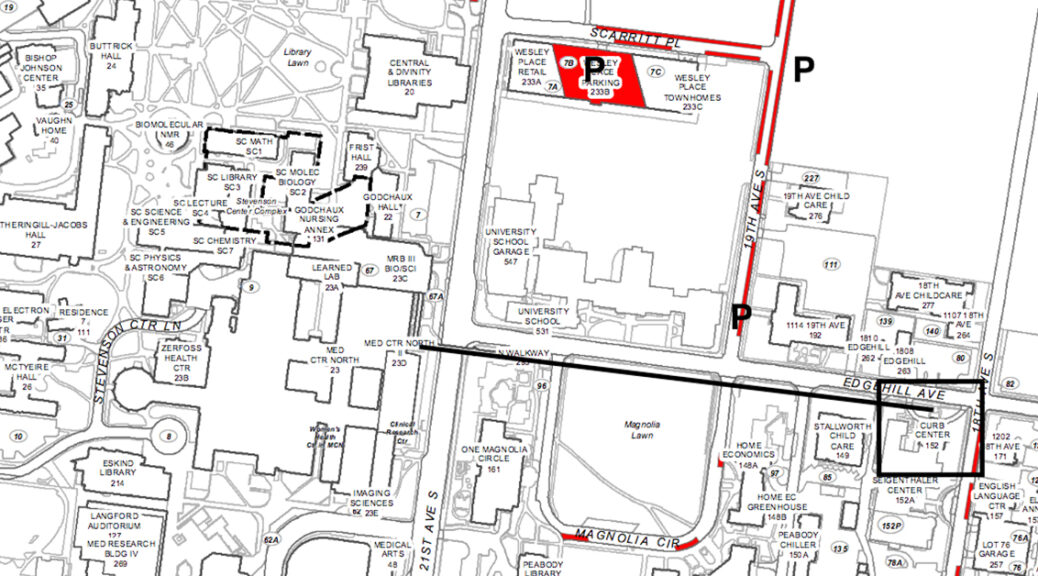

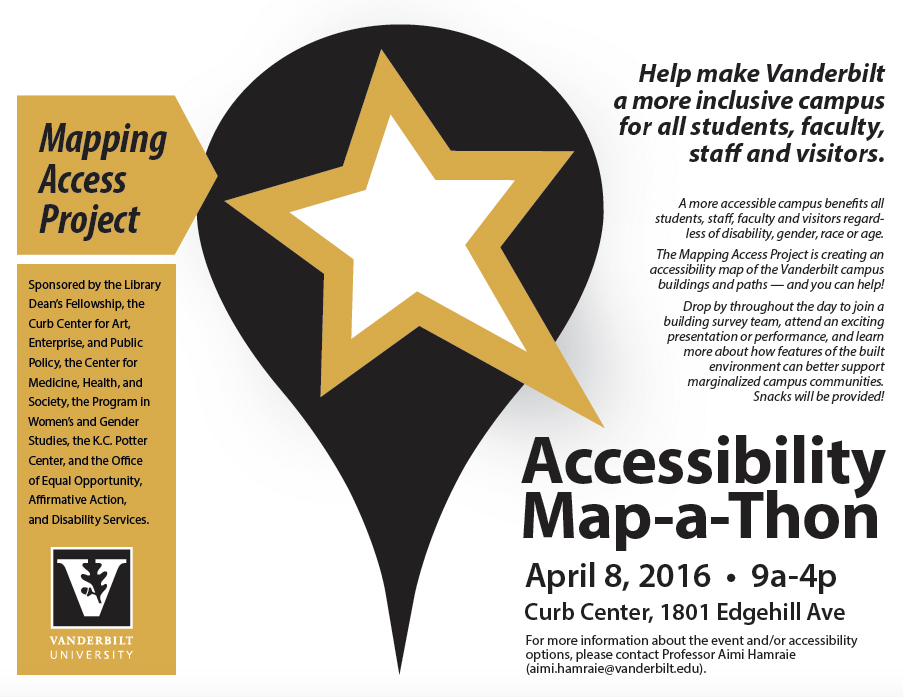

Leah Samples used geospatial data, participatory research, urban cartography and mobile technologies to achieve the aims of the project. Through the use of focus groups, project members were able to build and refine a survey that was ultimately managed in REDcap, a survey and data collection app created at Vanderbilt. Project members organized a one day Map-A-Thon where volunteers could add relevant data to a map of the University. In the Map-A-Thon, 120 participants surveyed the campus for accessible features and barriers and updated a live map with images and descriptive text so all participants could view the project’s progress and see which buildings were being mapped. . A live Twitter stream also allowed the team to track progress in real-time. The event featured panel discussions and speakers throughout the day highlighting the intersectional nature of disability studies.

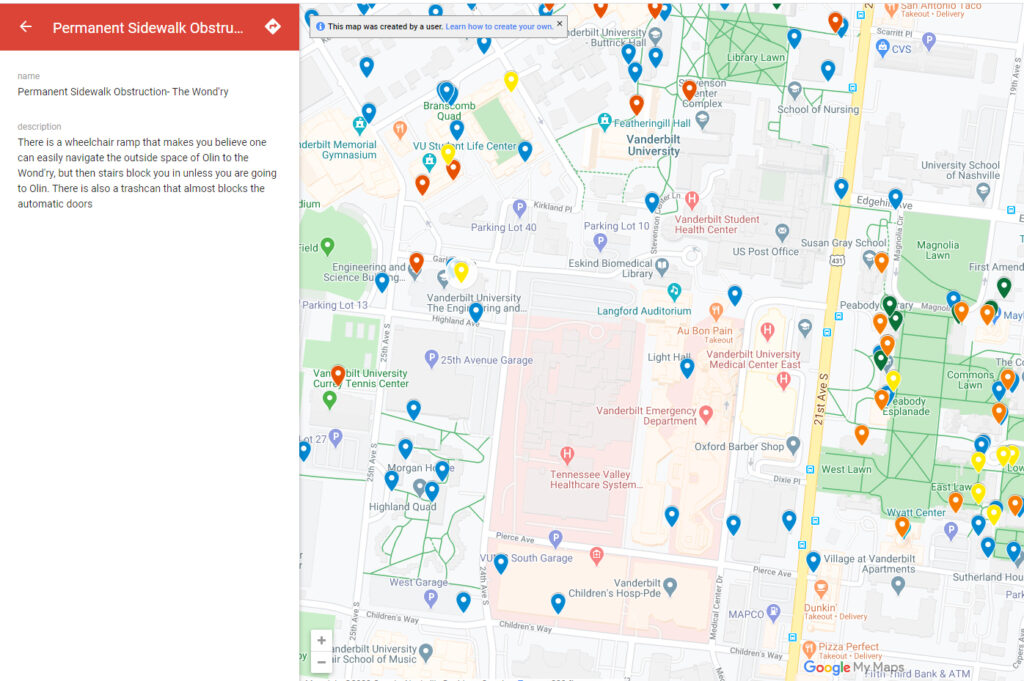

After gathering data from the live mapping event, team members reviewed and cleaned the data, they visualized the GIS data using R and Shiny, and they created JSON drafts that were edited in Atom. The resulting Campus Access Amenities Map examines not only accessible features such as automatic doors, ramps, and sidewalk obstructions (permanent and impermanent); it also highlights inclusive features such as all-gender bathrooms, lactation rooms, prayer and meditation spaces, showers and Blue Light Security stations.

In her article, “Mapping Access: Digital Humanities, Disability Justice, and Sociospatial Practice,“ project founder Aimi Hamrae analyzes the impact and impetus of projects like Mapping Access and their communitarian aims:

“New digital projects use geographic information systems (GIS) and crowdsourcing applications to gather data about the accessibility of public spaces for disabled people. While these projects offer useful tools, their approach to technology and disability is often depoliticized. Compliance-based maps take disability for granted as medical impairment and do not consider mapping as a humanistic and activist practice. This essay draws on digital humanities theories of “thick mapping” and critical disability theories of public citizenship to offer critical accessibility mapping as an alternative to compliance-focused mapping. Using Mapping Access as a case study, I frame digital mapping as a question-generating device, a site of narrative praxis, rather than mere data visualization. I argue that critical accessibility mapping offers a digital humanities-informed model of “sociospatial practice,” with several distinct benefits: it recognizes marginalized experts; redefines the concepts of data, crowdsourcing, and public participation; offers new stories about disability and public belonging; and materializes the principles of disability justice, an early twentieth-century movement emphasizing intersectionality and collective access.”

Digital accessibility maps are becoming more commonplace either through commercial apps or crowdsourced digital humanities projects like Mapping Access. These kinds of initiatives can not only yield direct and tangible results to help people with disabilities get around but more importantly, they offer critical insights into the built environment that can influence architects and policy makers to make meaningful changes to create accessible spaces for all.

citations

Elwood, S., Schuurman, N. & Wilson, W. (2011). Critical gis. In T. L. Nyerges H. Couclelis & R. McMaster The SAGE handbook of GIS and society(pp. 87-106). London: SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781446201046.n5

Hamraie, Aimi. “Mapping Access: Digital Humanities, Disability Justice, and Sociospatial Practice.” American Quarterly, vol. 70 no. 3, 2018, p. 455-482. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/704333

Hamraie, Aimi. Building Access : Universal Design and the Politics of Disability / Aimi Hamraie. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. Print.

https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/be14ds/alma991046135289706011