Vea abajo para versión en español / Veja em baixo para versão em português

In honor of World Digital Preservation Day, members of the University of Texas Libraries’ Digital Preservation team have written a series of blog posts to highlight preservation activities at UT Austin, and to explain why the stakes are so high in our ever-changing digital and technological landscape. This post is part four in a series of five. Read part one, part two, and part three.

By DAVID BLISS (@davidallynbliss), Digital Processing Archivist, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections @llilasbenson

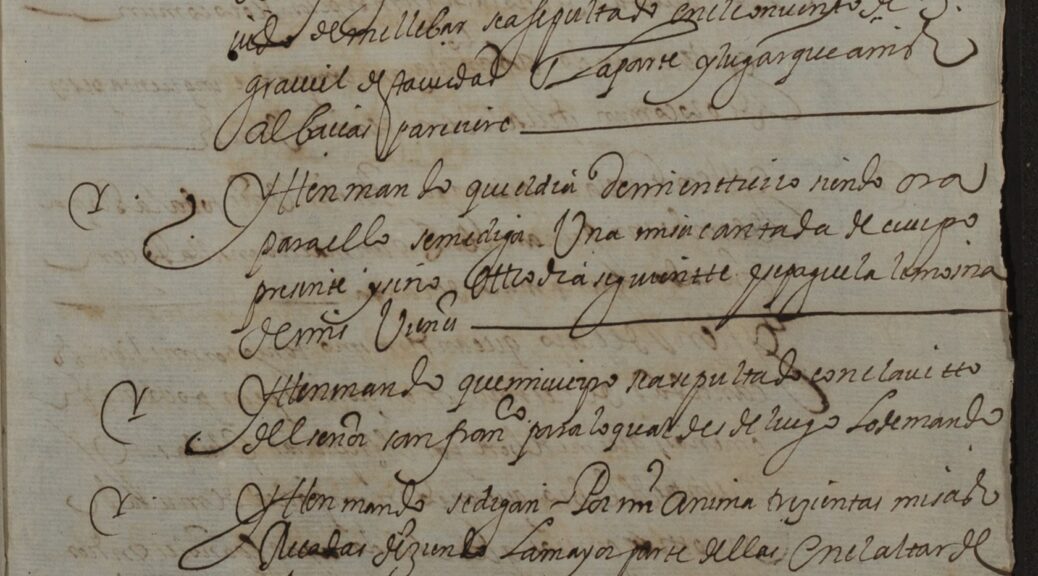

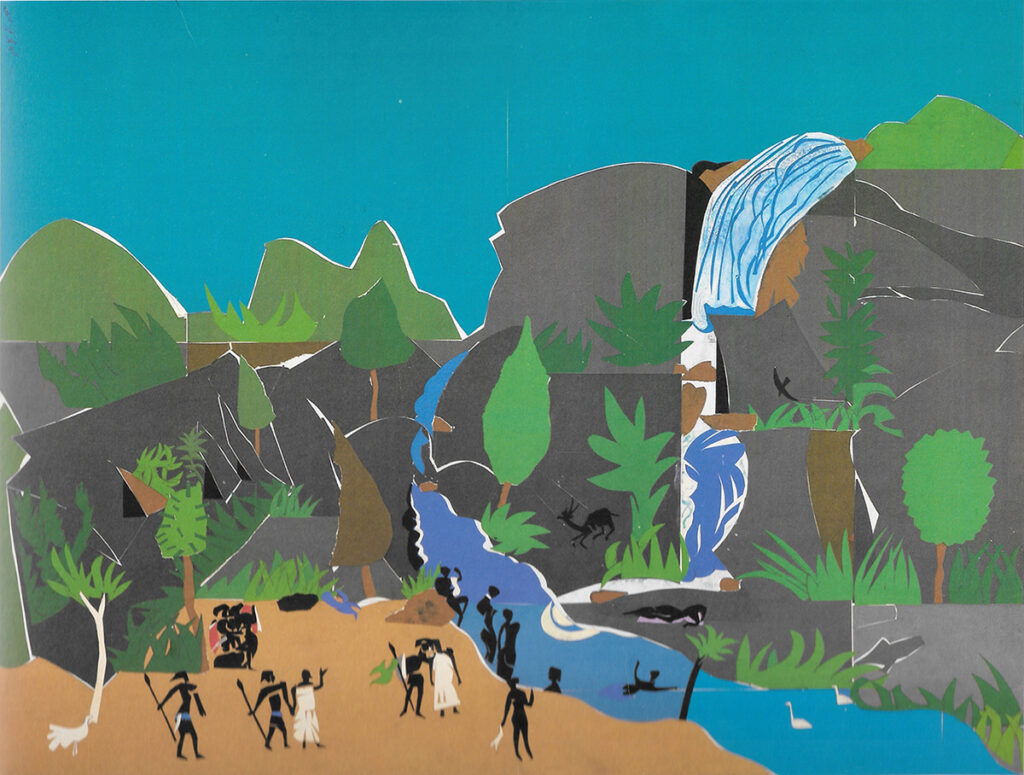

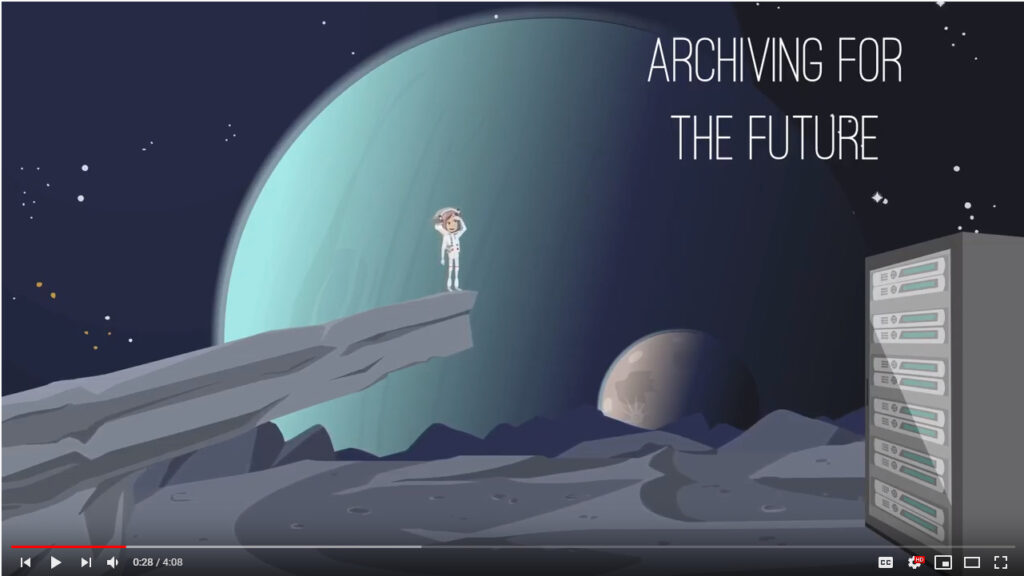

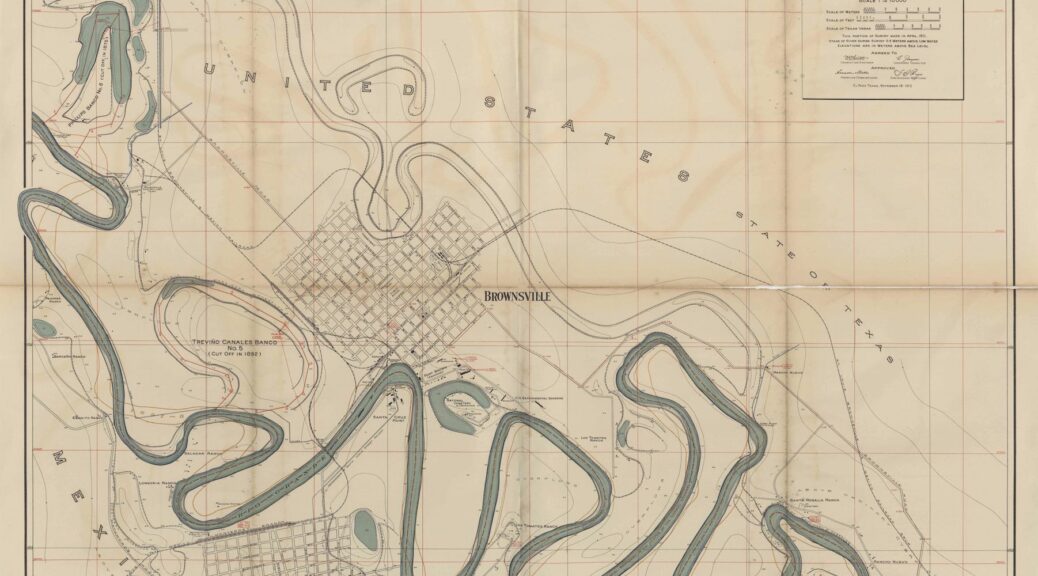

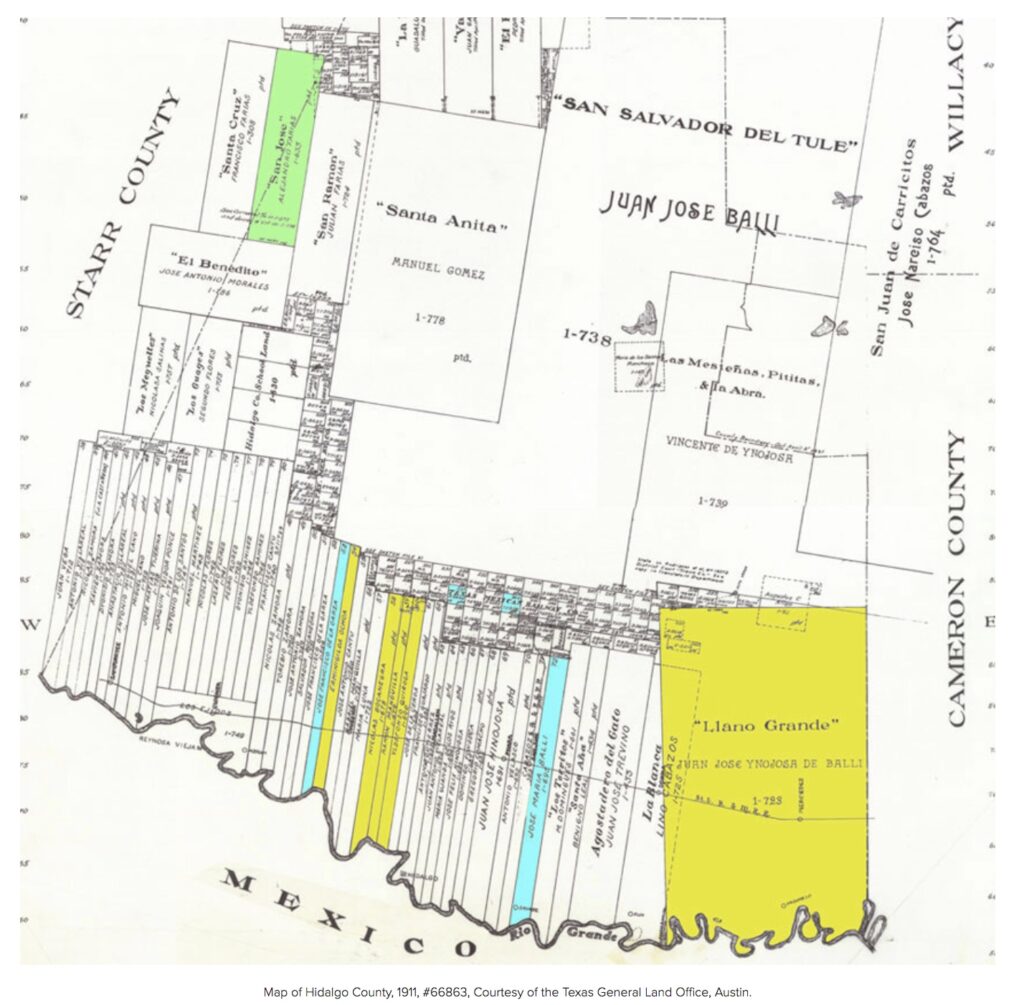

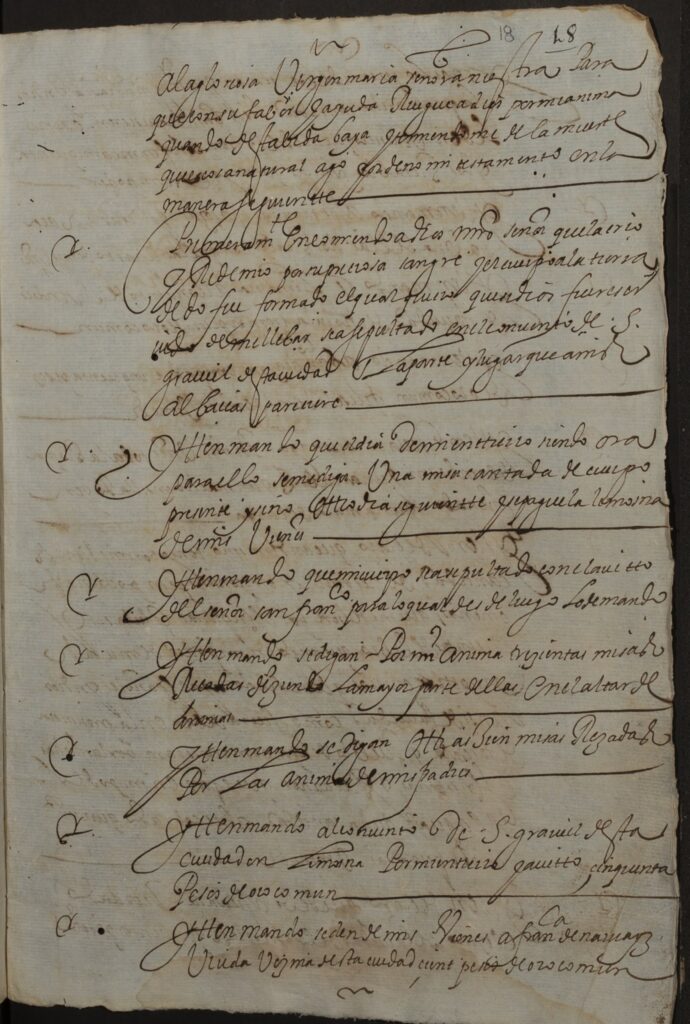

Over the past decade, LLILAS Benson has undertaken post-custodial archival projects in collaboration with partners throughout Latin America and beyond. Post-custodial archival practice encompasses a range of theory and methodology, built on the premise that digital technologies make it possible for collecting institutions like LLILAS Benson to provide access to archival collections from Latin America without taking physical custody or removing them from their original contexts of creation and use.

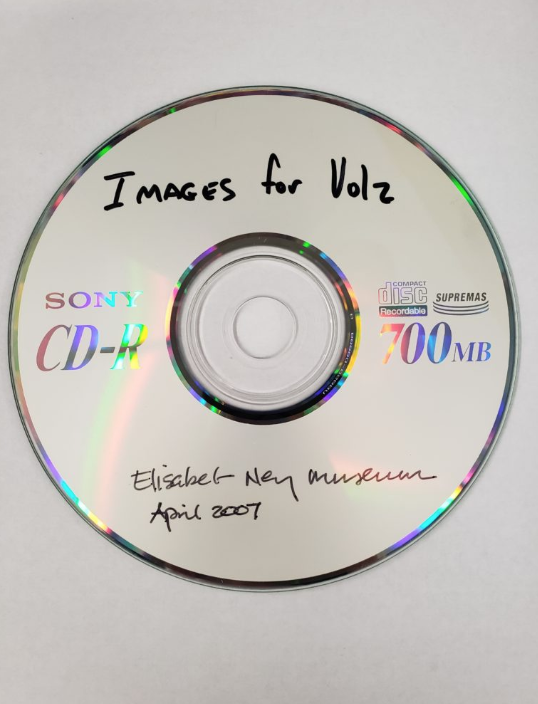

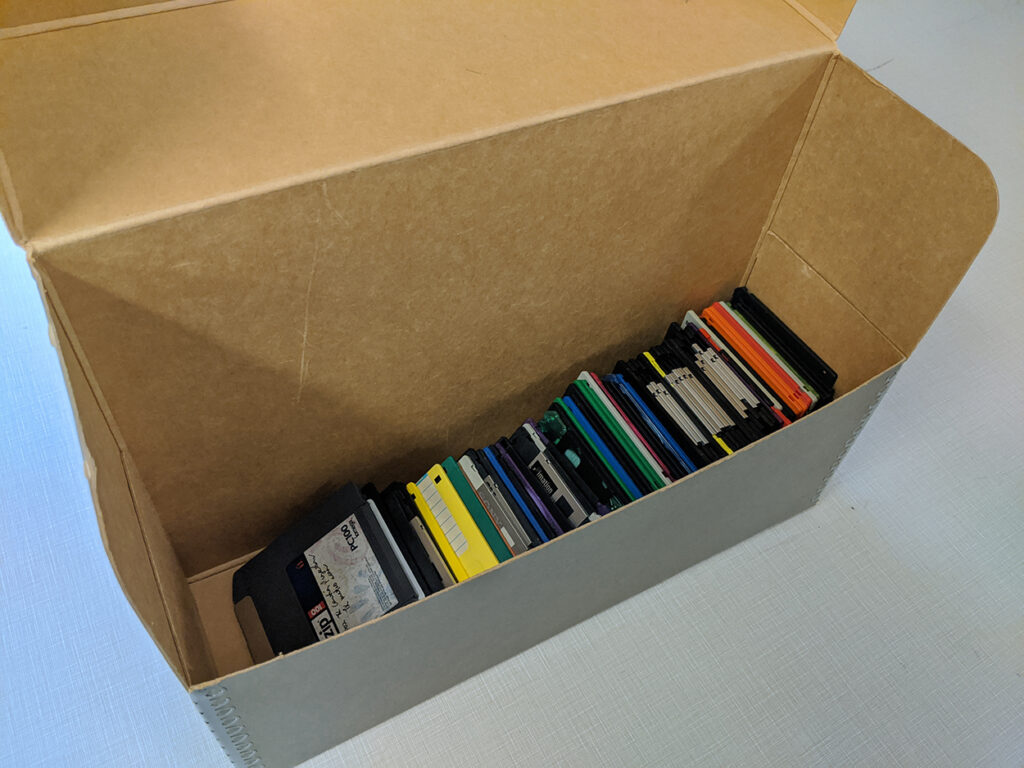

Through these post-custodial projects, LLILAS Benson staff and partner repository staff work together closely to identify collections of interest, select appropriate digitization equipment, and build metadata collection strategies. The materials are then digitized and described on-site in Latin America by partner repository staff. The digitized collections are then transferred to LLILAS Benson, where they are processed, preserved, and in most cases published online. Because the original collections are often vulnerable or sensitive, frequently touching on delicate human rights issues, long-term preservation of their digital copies is especially important to LLILAS Benson staff and partners in Latin America.

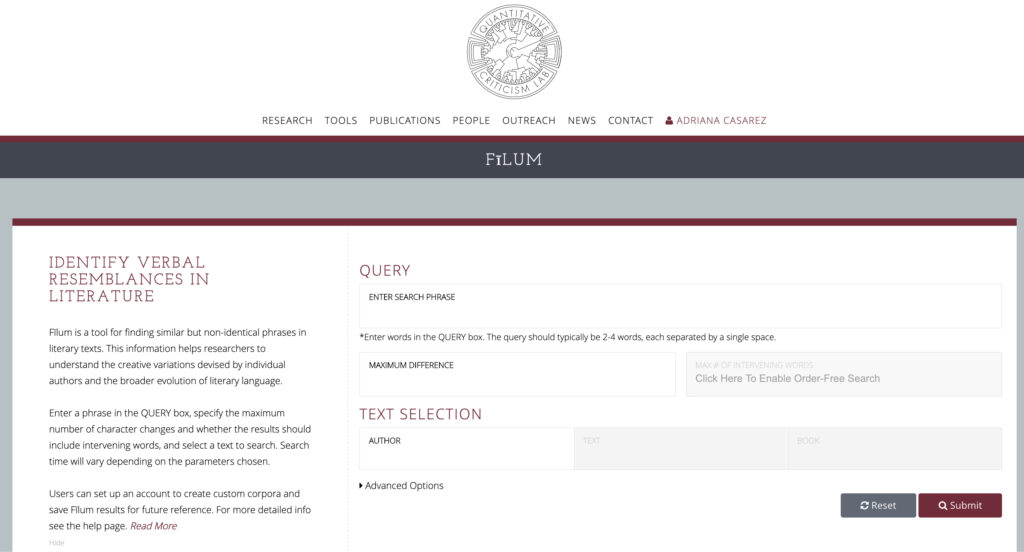

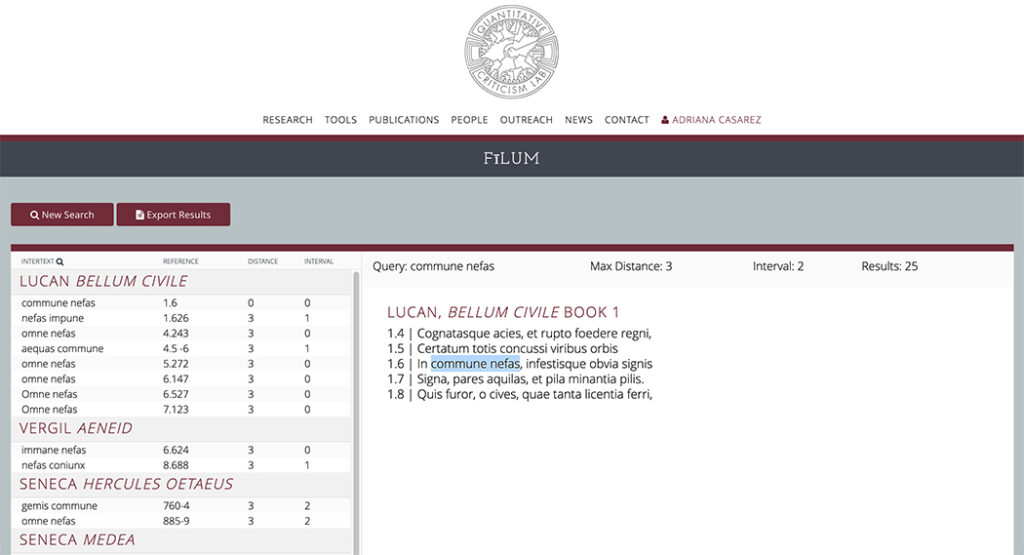

In recent years, the LLILAS Benson team has integrated file fixity checks in all post-custodial projects. When launching a project at a partner site, LLILAS Benson staff now teach project team members the basic principles of digital preservation and the importance of fixity checks, which verify that files have not been altered or corrupted over time. The project teams are taught to create and verify checksums prior to transferring a batch of files to LLILAS Benson, using free software available in Spanish or Portuguese.

These checksums now accompany all file deliveries from project sites, and help the LLILAS Benson team identify corrupted or missing files immediately. These checksums speed LLILAS Benson’s processing and preservation work, allowing the files to be published online and preserved long-term more easily. The checksum workflow also encourages each partner to include fixity checks in any future digitization projects they undertake, thus contributing to the partners’ own digital preservation capacity.

Equipo poscustodial LLILAS Benson

Traducido por Jennifer Isasi (@jenniferisve)

@llilasbenson

Durante la última década, LLILAS Benson ha emprendido proyectos de archivo de tipo poscustodial junto con socios a lo largo de América Latina. La práctica de archivo poscustodial abarca una serie de teorías y metodologías basadas en la premisa de que las tecnologías digitales hacen posible que las instituciones colectoras como LLILAS Benson provean acceso a las colecciones de archivos de Latinoamérica sin su custodia física o su eliminación del contexto original de su creación y uso.

A través de estos proyectos poscustodiales el personal de LLILAS Benson y sus colaboradores trabajan en estrecha colaboración para identificar colecciones de interés, seleccionar el equipo de digitalización adecuado y desarrollar estrategias de curaduría de metadatos. Los materiales son digitalizados y descritos en Latinoamérica por parte del personal de cada archivo para luego ser transferidos al equipo LLILAS Benson, quien procesa, preserva y publica los materiales en la mayoría de los casos. Debido a que las colecciones originales son a menudo vulnerables o con contenido delicado, y frecuentemente tocan temas relacionados con derechos humanos, la preservación a largo plazo de sus copias digitales es especialmente importante para el personal y los socios de LLILAS Benson en América Latina.

En años recientes, LLILAS Benson ha añadido verificaciones de permanencia de archivos en los proyectos poscustodiales en curso. Con el inicio de cada proyecto en el archivo de los colaboradores, el personal de LLILAS Benson enseña a cada equipo los principios básicos de preservación digital y la importancia de añadir verificaciones de permanencia, que verifican que los archivos no han sido alterados o dañados con el tiempo. Los equipos de los proyectos aprenden a crear y verificar sumas de verificación usando programas gratuitos en español o portugués antes de transferir un conjunto de archivos a LLILAS Benson.

Estas sumas de verificación ahora acompañan todas las entregas de archivos desde el lugar de los proyectos de digitalización y ayudan al equipo de LLILAS Benson a identificar archivos dañados o faltantes de inmediato. Esto acelera las tareas locales de procesamiento y preservación en LLILAS Benson y anima a cada colaborador a incluir controles de verificación en cualquier otro proyecto que puedan emprender en el futuro. Esto a su vez contribuye a la capacidad de preservación digital propia de los colaboradores.

Equipe pós-custodial da LLILAS Benson

Traduzido por Tereza Braga

@llilasbenson

Durante a última década, a LLILAS Benson empreendeu alguns projetos arquivísticos pós-custodiais, em colaboração com entidades parceiras espalhadas pela América Latina e outros lugares. A prática arquivística pós-custodial engloba uma gama de teorias e metodologias assentadas na premissa de que as tecnologias digitais possibilitam a instituições recolhedoras de coleções, como a LLILAS Benson, disponibilizar o acesso a coleções arquivísticas latino-americanas sem necessidade de obter custódia física ou a remoção das mesmas de seus contextos originais de criação e de uso.

Por meio desses projetos pós-custodiais, as equipes de profissionais da LLILAS Benson e dos repositórios parceiros trabalham em contato estreito para identificar coleções de interesse, selecionar o equipamento de digitalização adequado e criar estratégias de coleta de metadados. O material é então digitalizado e descrito pela equipe de repositório da entidade parceira em cada local específico da América Latina. Em seguida, as coleções digitalizadas são transferidas para a LLILAS Bensonm onde são processadas, preservadas e, na maioria dos casos, publicadas online. Devido ao fato de muitas coleções originais serem vulneráveis ou sensitivas por causa de referências frequentes a questões delicadas de direitos humanos, a preservação a longo prazo de cópias digitais é especialmente importante para a equipe da LLILAS Benson e entidades parceiras na América Latina.

Em anos recentes, os profissionais da LLILAS Benson vêm integrando verificações de fixidez de arquivos em todos os projetos pós-custodiais. Agora, ao lançar um projeto em local parceiro, a equipe ensina às equipes do projeto os princípios básicos da preservação digital e a importância das verificações de fixidez para constatar se os arquivos não foram alterados ou corrompidos ao longo do tempo. As equipes de projeto aprendem a criar e verificar as checksums (somas de verificação) antes de transferir qualquer lote de arquivos para a LLILAS Benson, usando software gratuito disponível em espanhol e português.

Essas checksums já acompanham todas as entregas de arquivos oriundos de locais de projetos e ajudam a equipe da LLILAS Benson a identificar imediatamente arquivos corrompidos ou faltando. As checksums aceleram o trabalho de processamento e preservação da LLILAS Benson, permitindo publicar os arquivos online e preservá-los a longo prazo com mais facilidade. O fluxograma de checksums também incentiva cada entidade parceira a incluir verificações de fixidez em qualquer projeto de digitalização a ser empreendido no futuro contribuindo, assim, para a própria capacidade de preservação digital de cada entidade.