Vea abajo para versión en español / Veja em baixo para versão em português

In honor of World Digital Preservation Day, members of the University of Texas Libraries’ Digital Preservation team have written a series of blog posts to highlight preservation activities at UT Austin, and to explain why the stakes are so high in our ever-changing digital and technological landscape. This post is part three in a series of five. Read part one and part two.

By SUSAN SMYTHE KUNG, PhD, Manager, (@SusanKung), and RYAN SULLIVANT, PhD, Language Data Curator, (@floatingtone), Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America @AILLA_archive

At AILLA, we are developing guidelines for language researchers and activists that are intended to facilitate the organization and ingestion of their collections of recordings and annotations of Indigenous, and often endangered, languages into digital repositories so that these valuable digital resources can be preserved for the future. One of the areas of focus for these guidelines is on the importance of using open and sustainable file formats to increase the likelihood that digital files can be opened and read in the future. To help explain these ideas, we produced a short animated video that is available under a Creative Commons license on YouTube at https://youtu.be/2JCpg6ICr8M.

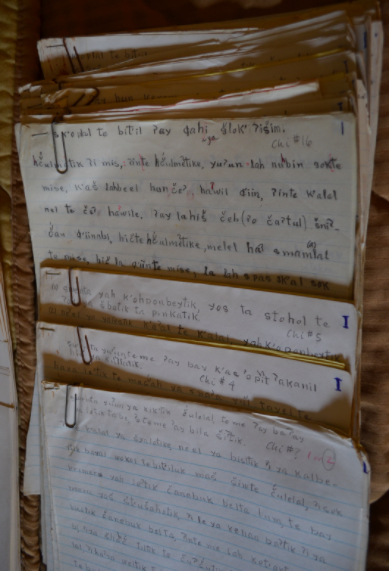

Many digital documents are produced using proprietary software, and future users will need to have the same, or similar, software to open the files or read their contents. While documents in proprietary formats can be put into a digital repository so their bitstreams (all the ones and zeroes) are preserved well into the future, the exact copy of the file a user downloads years from now may be impossible to use if the proprietary software it was made with is no longer available. Documents preserved in these non-open and non-sustainable formats then end up like cuneiform tablets: objects whose marks and features have survived a long passage through time but can only be read by a small number of people after considerable effort and study.

Choosing sustainable open formats helps ensure that materials are not just preserved but are accessible and usable into the future, since open-source applications can be more easily built to read files stored in non-proprietary formats.

Archivo de las Lenguas Indígenas de Latinoamérica

Traducido por Jennifer Isasi

@AILLA_archive

En AILLA (por sus siglas en inglés), estamos desarrollando pautas para lingüistas y activistas con la intención de facilitar la organización e ingesta de sus colecciones de materiales de documentación de idiomas en repositorios digitales para que estos valiosos recursos digitales puedan conservarse para el futuro. Una de las áreas que resaltamos en estas guías es la importancia de utilizar formatos de archivo abiertos y sostenibles para aumentar la probabilidad de que estos archivos digitales puedan ser abiertos y leídos en el futuro. Para explicar estas ideas hemos producido un video animado corto que está disponible con licencia de Creative Commons en Youtube: https://youtu.be/2JCpg6ICr8M.

Muchos documentos digitales se producen con software propietario y se necesita el mismo software (o un software parecido) para abrirlos o leer su contenido. Es cierto que se puede meter documentos en formatos propietarios en un repositorio digital y sus bitstreams (todos los unos y ceros) serán preservados hasta el futuro, pero cuando el usuario del futuro lo descarga, no existe garantía de que aquella copia fiel sea accesible porque es posible que el software necesario ya no exista. Los documentos así preservados en formatos no abiertos y no sostenibles entonces terminan como tableta escritas en cuneiforme cuyas marcas y figuras han sobrevivido tras el tiempo pero solo son legibles por un pequeño conjunto de personas muy especializadas.

Escoger formatos sostenibles y abiertos ayuda a asegurar que los materiales no solo permanezcan sino que estén accesibles y útiles en el futuro ya que será más fácil crear una aplicación de fuente abierta para leer archivos almacenados en formatos no propietarios.

Arquivo dos Idiomas Indígenas da América Latina

Traduzido por Tereza Braga

@AILLA_archive

Na AILLA, estamos desenvolvendo diretrizes para pesquisadores linguísticos e ativistas com o objetivo de possibilitar a organização e inserção de suas coleções de gravações e observações em idiomas indígenas (muitos em perigo de extinção) em repositórios digitais para que esses valiosos recursos possam ser preservados para o futuro. Uma das áreas de enfoque para essas diretrizes é a importância de utilizar formatos de arquivo abertos e sustentáveis para aumentar a probabilidade de que esses arquivos digitais possam ser abertos e lidos no futuro. Para ajudar a explicar essas ideias, produzimos um vídeo curto com técnica de animação, que está disponibilizado sob licença da Creative Commons no YouTube, em https://youtu.be/2JCpg6ICr8M.

Muitos documentos digitais são produzidos utilizando software proprietário. Assim sendo, o usuário do futuro terá que ter o mesmo software ou similar para poder abrir os arquivos ou ler seus conteúdos. É viável armazenar documentos criados em formatos proprietários em repositório digital, para que seus bitstreams (todos os uns e todos os zeros) sejam preservados por muitos e muitos anos; por outro lado, é também possível que a cópia exata do arquivo baixado pelo usuário daqui a muitos anos seja impossível de utilizar, se o software proprietário que o criou não esteja mais disponível. Documentos preservados nesses formatos não-abertos e não-sustentáveis podem acabar como as táboas de escrita cuneiforme: objetos cujas marcações e funcionalidades sobreviveram uma longa passagem pelo tempo mas só podem ser lidos por um número pequeno de pessoas após considerável esforço e estudo.

A seleção de formatos abertos e sustentáveis ajuda a garantir que certos materiais sejam não só preservados mas também acessíveis e utilizáveis no futuro, considerando que é mais fácil construir aplicações de código-fonte aberto capazes de ler arquivos armazenados em formatos não-proprietários.