Two members of the LLILAS Benson Digital Initiatives team recently visited Buenaventura, Colombia, to work with archivists and community leaders at Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN), a grassroots collective of organizations founded in 1993 that is working to transform the political, social, economic, and territorial reality of Colombia’s Black, Afro-descendant, Raizal, and Palenquera communities through the defense and revindication of their individual, collective, and ancestral rights.

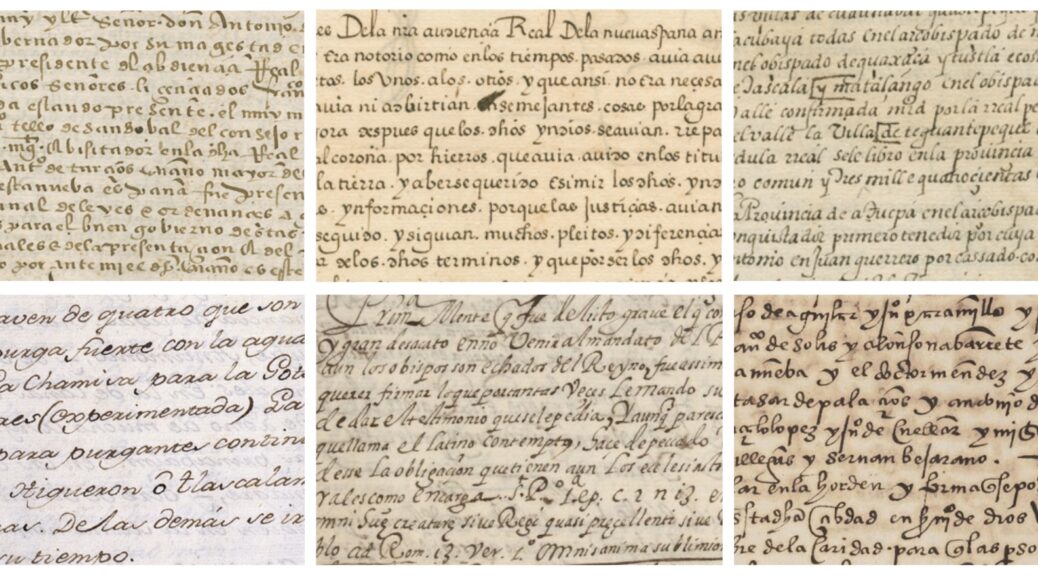

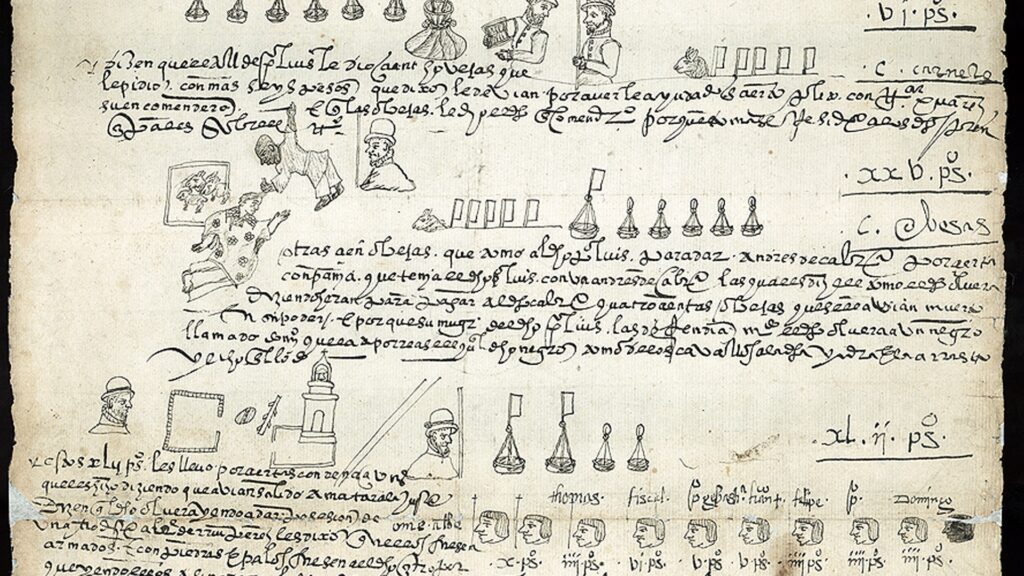

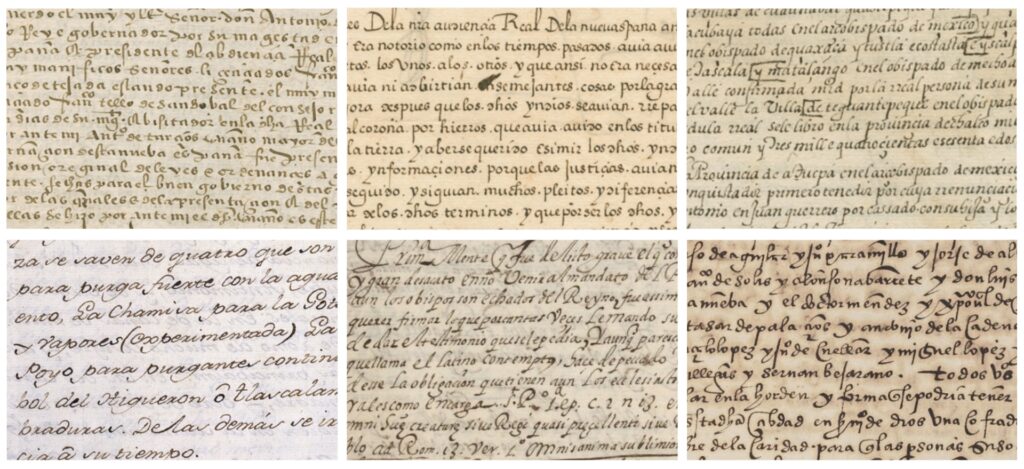

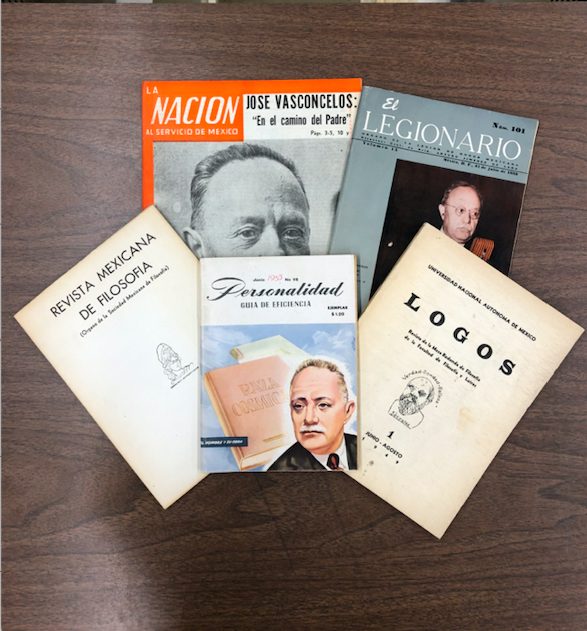

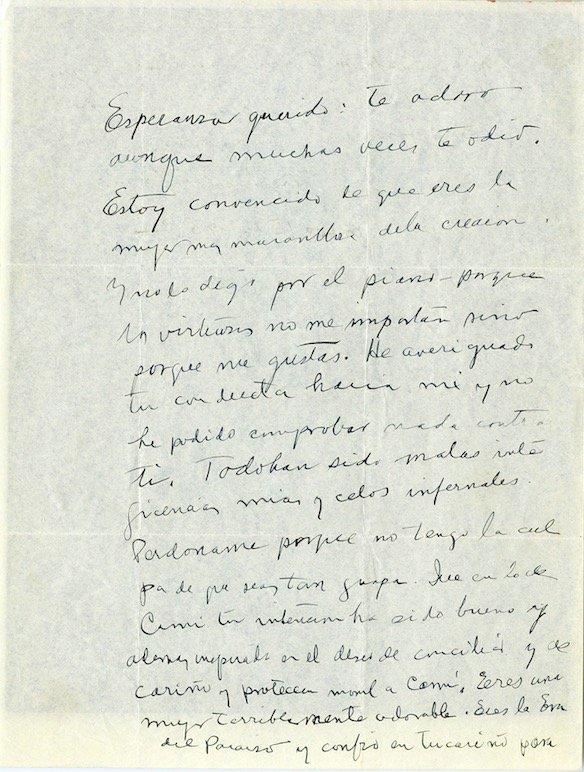

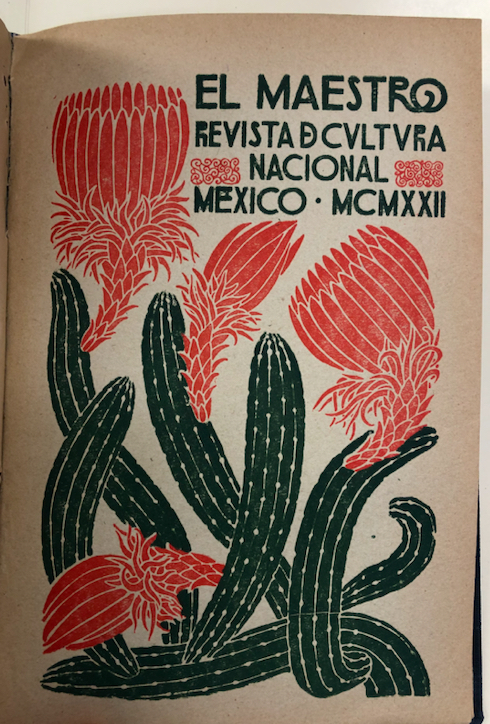

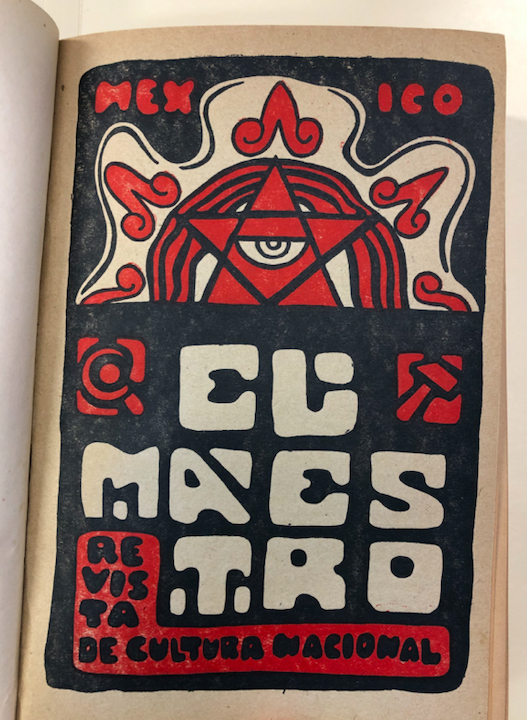

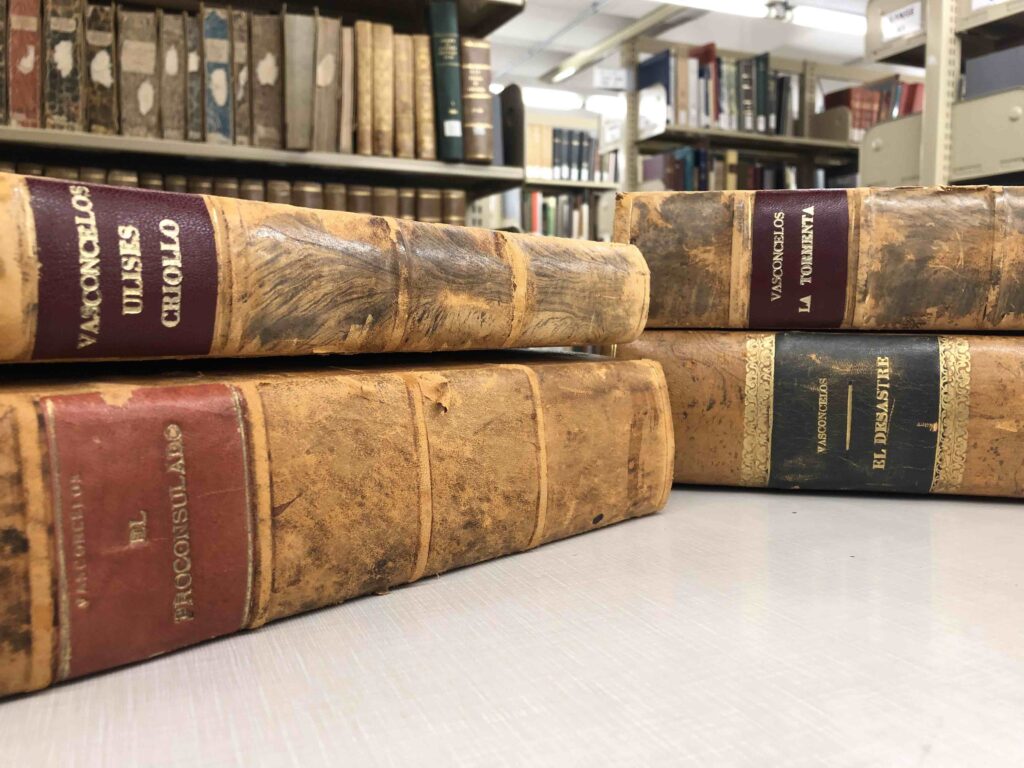

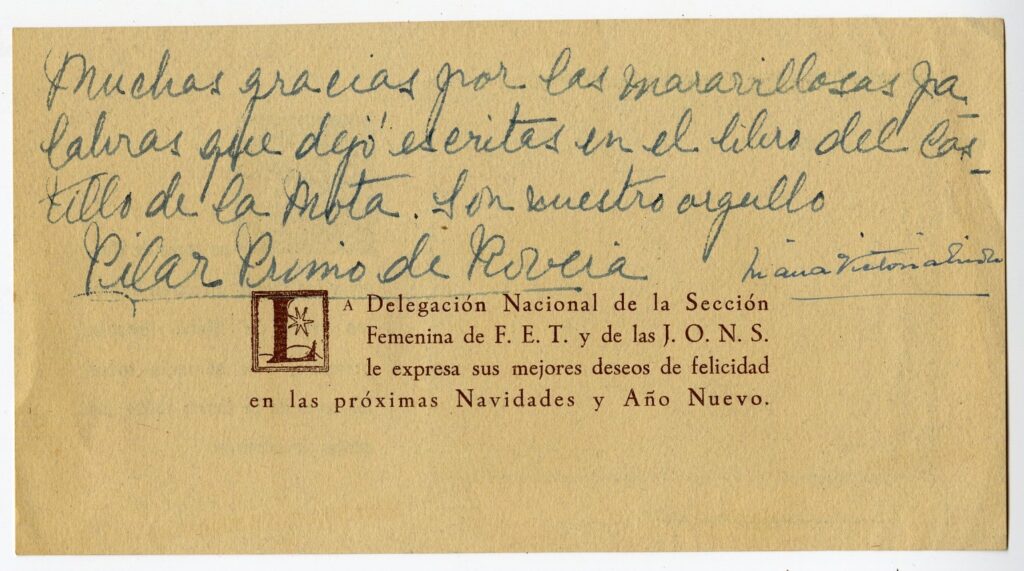

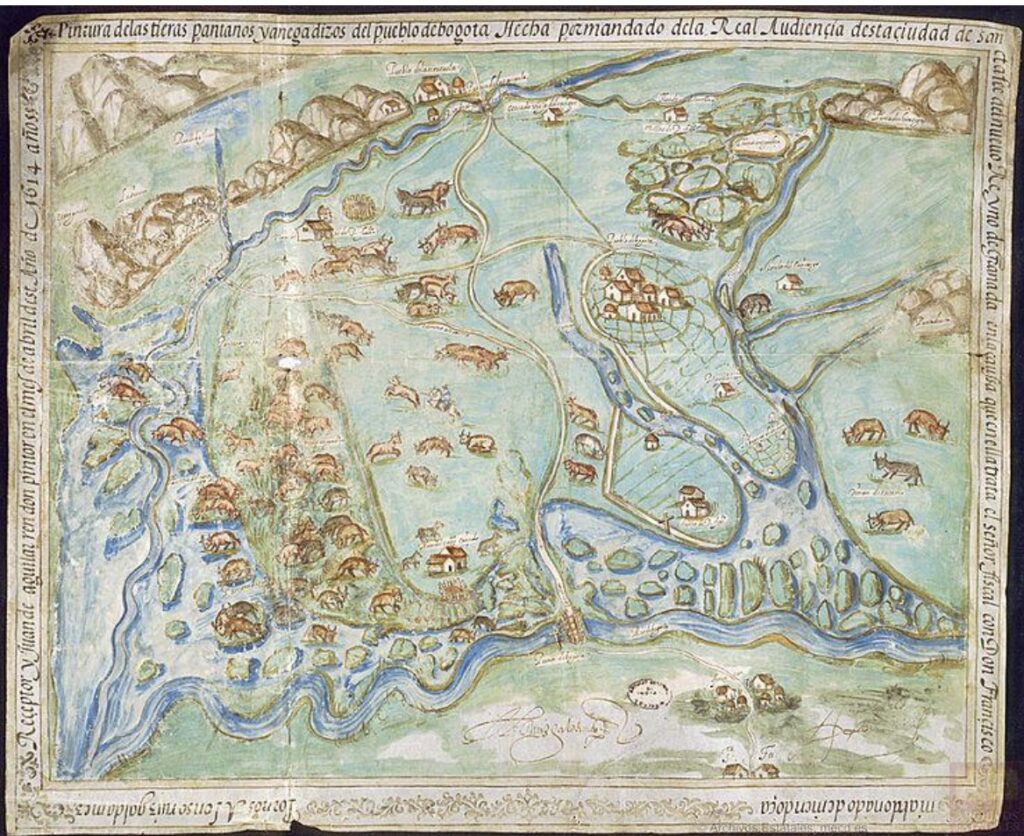

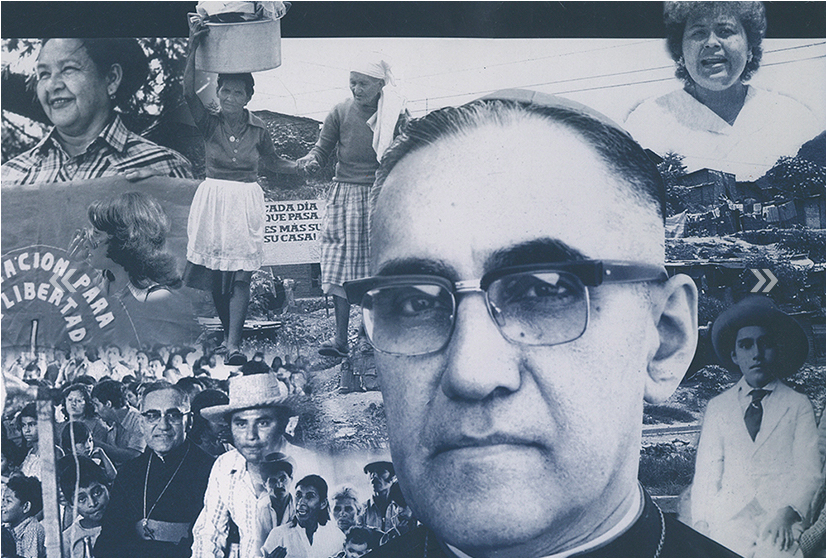

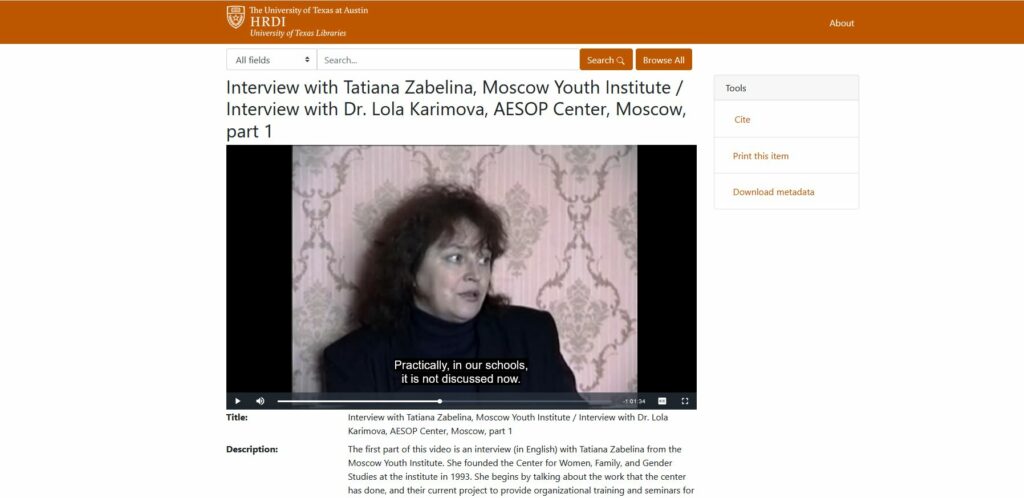

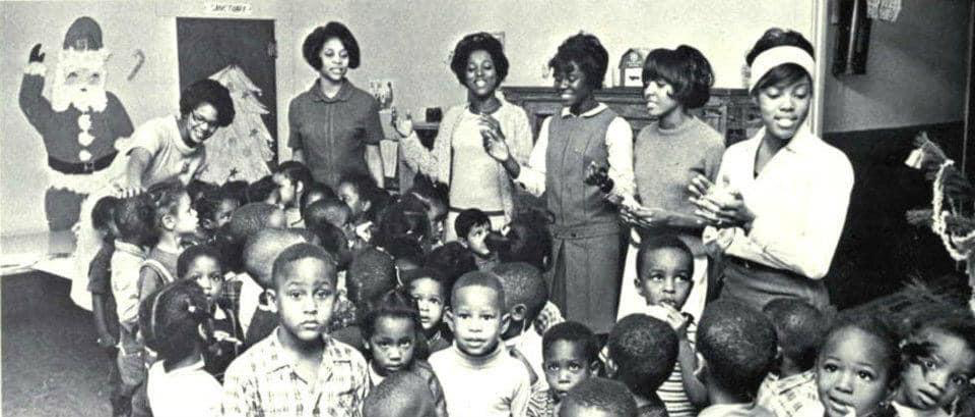

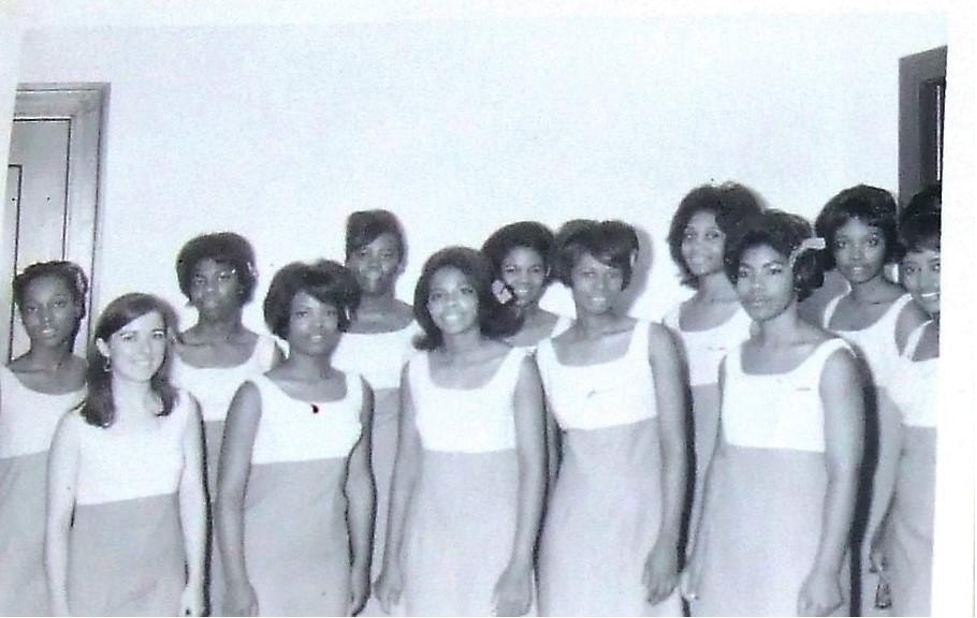

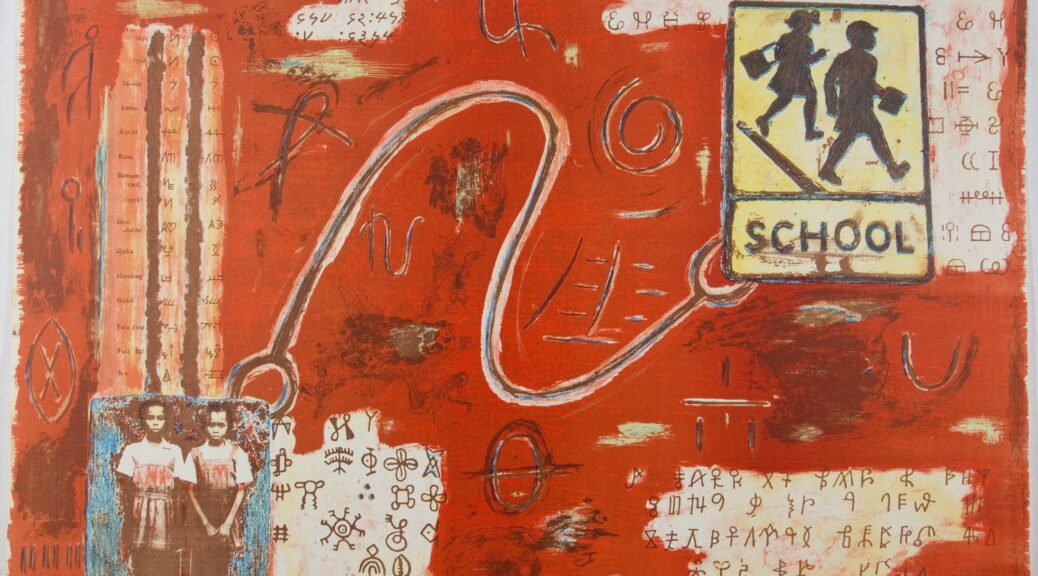

PCN participates as one of several sister archives with which LLILAS Benson has developed a partnership to support the digitization and description of archival materials. Funded by a succession of grants from the Mellon Foundation, this project emphasizes the post-custodial archiving model.* Digitized materials from PCN’s Colección Dinámicas Organizativas del Pueblo Negro en Colombia archive.

Alex Suarez, Digital Projects Archivist, and Karla Roig, former Post-Custodial and Digital Initiatives Graduate Research Assistant, spent a week in Buenaventura to assist PCN with organizing and processing their physical collection. By processing the physical collection, PCN will be able to digitize and create metadata more efficiently. Below, Suarez (AS) and Roig (KR) answer questions about this meaningful visit.

Please describe what you did while visiting Colombia.

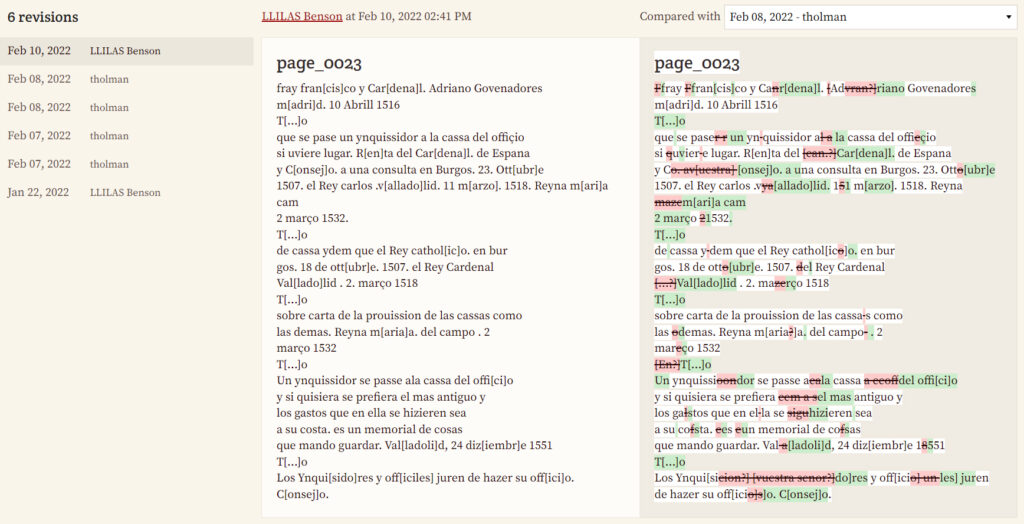

AR: We conducted a series of trainings on archival processing, metadata creation, and digitization. We also had the opportunity to learn about the region as well as the city of Buenaventura. The first few days were spent getting to know the collection and to also understand how PCN works as an organization.

Together with PCN, we brainstormed how to arrange the archive in a way that reflects how PCN operates and how they envisioned using the archive in the future. We also reviewed digitization and metadata best practices so that PCN materials can be accessible worldwide and researchers can learn about the organization and Buenaventura.

We were also invited to attend throughout the week three talks titled “Diálogos ribereños,” organized by PCN and the Banco de la República, in which community leaders engaged in conversation with the community around topics of burial rites, economic practices and the environment, and the settlement of their rivers.

Please share some of the highlights of the trip: the setting, activities, and accomplishments.

AR: I was blown away by the closeness of the community and the work they have accomplished over the last 30 years. Everybody knows each other and have been working toward the same goals. It was so interesting to see the community at work.

One of the biggest accomplishments was PCN creating their archival processing plan and defining their arrangement plan. Some of my favorite moments were spent drinking freshly brewed coffee around [PCN leader] Marta’s dining room table talking about how to arrange the archive and how they envisioned future researchers using the archive.

Another favorite moment was attending an interactive exhibit titled Río la Verdad, by Bogotá-based artist Leonel Vásquez, who installed a swimming pool where guests could submerge themselves and hear the sound of the rivers and people singing songs about their history. It was a deeply powerful experience and one that I will never forget.

KR: About the setting: On Sunday morning, we met with Marta and she showed us around Buenaventura for the first time. Our hotel was in front of the Malecón, their only public park, where people gather early in the morning to wait for the small boats that will connect them to other parts of the Colombian Pacific coast. Walking around the small coastal city, there were many local stores and street vendors displaying their goods—from fruits and vegetables, clothes and shoes, to home essentials. Right away we could sense the tight-knit community bonds. Everyone we passed greeted us with a “Buenos días” and Marta was often stopped by people she knew to have a small conversation.

We stopped at a small coffee shop with the view of the Pacific Ocean to have a refreshing drink, where we talked about geography, how Colombia is divided into different departments, and how Buenaventura is the biggest municipality in the Valle del Cauca department. We were staying in the urban center of the municipality, which is where one of the major ports in the country that brings in a large percentage of imported goods is located. Seeing the large yellow container cranes was impressive, they spotted the skyline from our hotel view to the right, and to the left, on a clear day, we could see the mountains at a distance.

One of my favorite memories from our visit was the cultural exchange that happened between us and the PCN team. They taught us about their colloquialisms and their native fruits such as maracuyá and borojó (we tried them too!) and we shared our own vernacular from Puerto Rican and Cuban Spanish. It was exciting to find the similarities between our cultures as well as learning about the uniqueness of their own: how their communities are based around their rivers and also how the marimba is one of their traditional music instruments. Definitely the highlight of the entire visit for me was how welcoming and friendly the PCN team was, and how excited they were to engage with us at a professional and personal level. Toward the end of the week, we had a team dinner to celebrate what we had accomplished and to thank them for hosting us. That night we talked at length about the week, and we all shared what we had learned and were grateful for. It was a beautiful moment interspersed with conversation centered on the archive, but also with laughter and familiarity.

Any ongoing goals?

The main ongoing goal for LLILAS Benson’s Mellon-funded collaboration with PCN is to continue working on the physical archive and to arrange the materials in a way that reflects the organization.

Note: Post-custodial archiving is a process whereby sometimes vulnerable archives are preserved digitally and the digital versions made accessible worldwide, thus increasing access to the materials while ensuring they remain in the custody and care of their community of origin.

Lea este artículo en español:

Equipo de Iniciativas Digitales visita socios en Buenaventura, Colombia

Dos miembros del equipo de Iniciativas Digitales de LLILAS Benson viajaron recientemente a Buenaventura, Colombia, para trabajar con archivistas y líderes comunitarios de Proceso de Comunidades Negras (PCN), una colectiva de organizaciones fundada en 1993 que trabaja para transformar la realidad política, social, económica y territorial de las comunidades negras, afro-descendientes, raizal y palenqueras colombianas a través de la defensa y reivindicación de sus derechos individuales, colectivas y ancestrales.

Como archivo, PCN participa en una colaboración con LLILAS Benson para apoyar la digitalización y descripción de la Colección Dinámicas Organizativas del Pueblo Negro en Colombia. El proyecto, se está realizando a través del modelo de archivos pos-custodiales* y es apoyado por la Fundación Mellon.

Alex Suarez, Archivista para Proyectos Digitales, y Karla Roig, Asistente Posgrado de Investigaciones para Iniciativas Digitales, pasaron una semana en Buenaventura para ayudar a PCN a organizar y procesar su colección física. Al procesar la colección física, podrían digitalizar y crear metadatos de una manera más eficiente. Abajo, Suarez (AS) y Roig (KR) contestan algunas preguntas sobre la visita.

Expliquen, por favor, las actividades que realizaron durante su visita.

AS: Llevamos a cabo una serie de capacitaciones sobre el procesamiento de archivos, la creación de metadatos y la digitalización. También tuvimos la oportunidad de conocer sobre la región, así como la ciudad de Buenaventura. Los primeros días fueron dedicados a conocer la colección y también a comprender cómo funciona PCN como organización.

Junto con PCN, aportamos ideas sobre cómo organizar el archivo de una manera que reflejara cómo opera PCN y cómo imaginaban usar el archivo en el futuro. También revisamos las mejores prácticas de digitalización y metadatos para que los materiales de PCN puedan ser accesibles en todo el mundo y los investigadores puedan aprender sobre la organización y sobre Buenaventura.

También fuimos invitadas a asistir a lo largo de la semana a tres charlas tituladas “Diálogos ribereños”, organizadas por PCN y el Banco de la República, en las que líderes comunitarios conversaron con la comunidad en torno a temas de ritos fúnebres, prácticas económicas y medio ambiente, y del poblamiento de sus ríos.

¿Cuáles fueron los eventos más destacados del viaje en términos del lugar, las actividades, los logros?

AS: Quedé asombrada por la cercanía de la comunidad y el trabajo que han realizado durante los últimos 30 años. Todos se conocen unos a otros y han estado trabajando hacia unas metas en común y fue muy interesante ver a la comunidad haciendo ese trabajo.

Uno de los mayores logros fue PCN creando su plan de procesamiento de archivos y definiendo su plan de organización. Algunos de mis momentos favoritos fueron bebiendo café recién colado alrededor de la mesa del comedor de Marta hablando sobre cómo organizar el archivo y cómo imaginaban que los futuros investigadores usarían el archivo.

Otro de mis momentos favoritos fue asistir a una exhibición interactiva que fue instalada en el parque principal durante nuestra estadía. La exposición se tituló Río la Verdad del artista bogotano Leonel Vásquez, quien instaló una piscina donde los invitados podían sumergirse y escuchar el sonido de los ríos y la gente cantando canciones sobre su historia. Fue una experiencia profundamente poderosa y una que nunca olvidaré.

KR: Sobre el lugar: El domingo por la mañana nos reunimos con Marta [una líder de PCN] y ella nos caminó por Buenaventura por primera vez. Nuestro hotel estaba frente al Malecón, el único parque público de la ciudad, donde la gente se reúne temprano en la mañana para esperar las pequeñas embarcaciones que los conectarán con otras partes de la costa pacífica colombiana. Caminando por la pequeña ciudad costera, había muchas tiendas locales y vendedores en la calle que mostraban sus productos, desde frutas y verduras, ropa y zapatos, hasta artículos para el hogar. Inmediatamente pudimos ver la cercanía de la comunidad, a todo el que pasábamos nos saludaba con un “Buenos días”, y Marta a menudo paraba a hablar con algún conocido u otro para tener una pequeña conversación.

Nos detuvimos en una pequeña cafetería con vistas al Océano Pacífico para tomar una bebida refrescante en donde conversamos sobre la geografía, cómo Colombia está dividido en diferentes departamentos, y cómo Buenaventura es el municipio más grande del departamento del Valle del Cauca. Nos estábamos quedando en el centro urbano del municipio, que es dónde se encuentra uno de los puertos más importantes del país que trae un gran porcentaje de mercancías importadas. Ver las grandes grúas amarillas de contenedores fue impresionante, se percibían hacia la derecha del horizonte desde la vista de nuestro hotel, y a la izquierda, en un día claro, podíamos ver las montañas a lo lejos.

Uno de mis mejores recuerdos de nuestra visita fue el intercambio cultural que ocurrió entre nosotros y el equipo de PCN. Ellos nos enseñaron sobre sus coloquialismos y sus frutas nativas como el maracuyá y el borojó (¡también los probamos!) y compartimos nuestro vernáculo del español puertorriqueño y cubano. Fue emocionante encontrar las similitudes entre nuestras culturas, así como aprender sobre la singularidad de la de ellos: cómo sus comunidades se basan en sus ríos y también cómo la marimba es uno de sus instrumentos musicales tradicionales.

Definitivamente, lo que más se destacó de toda la visita para mí fue lo acogedor y amable que fue el equipo de PCN, y lo emocionados que estaban de interactuar con nosotros a nivel profesional y personal. Hacia el final de la semana, tuvimos una cena de equipo para celebrar lo que habíamos logrado y agradecerles por recibirnos. Esa noche hablamos sobre la semana y todos compartimos lo que habíamos aprendido y por lo que estábamos agradecidos. Fue un hermoso momento intercalado con conversación enfocada en el archivo, pero también con risas y familiaridad.

¿Objetivos para el futuro?

El principal objetivo de la subvención Mellon es continuar trabajando en el acervo físico y organizar los materiales de una manera que refleje la organización.

Nota: La práctica de archivos pos-custodiales tiene que ver con la preservación de archivos vulnerables en su lugar de origen, mientras se crea una versión digital del material para hacerlo disponible a nivel global.