BY DANIEL ARBINO

Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the UT Libraries Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of, and future creative contributions to, the growing fields of digital scholarship.

At a recent talk I gave, an audience member asked me, “What are the strengths of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection?”

It’s a question I receive often, though I don’t know if I’ve ever given a satisfactory answer. I often point to our historical Mexican archival collections, our collections of women writers and artists, and our US Latinx collections pertaining to civil rights. The truth is that I think the Benson does everything well. We have outstanding Brazilian collections, unique and important Caribbean materials, and strong representation in the Southern Cone. We know we can’t collect everything, but we sure try to anyway.

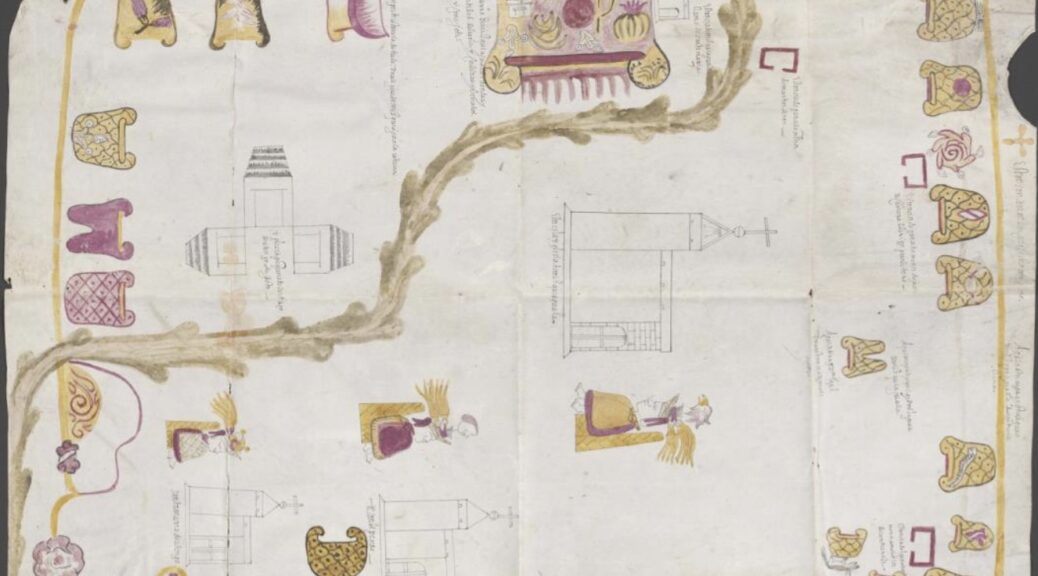

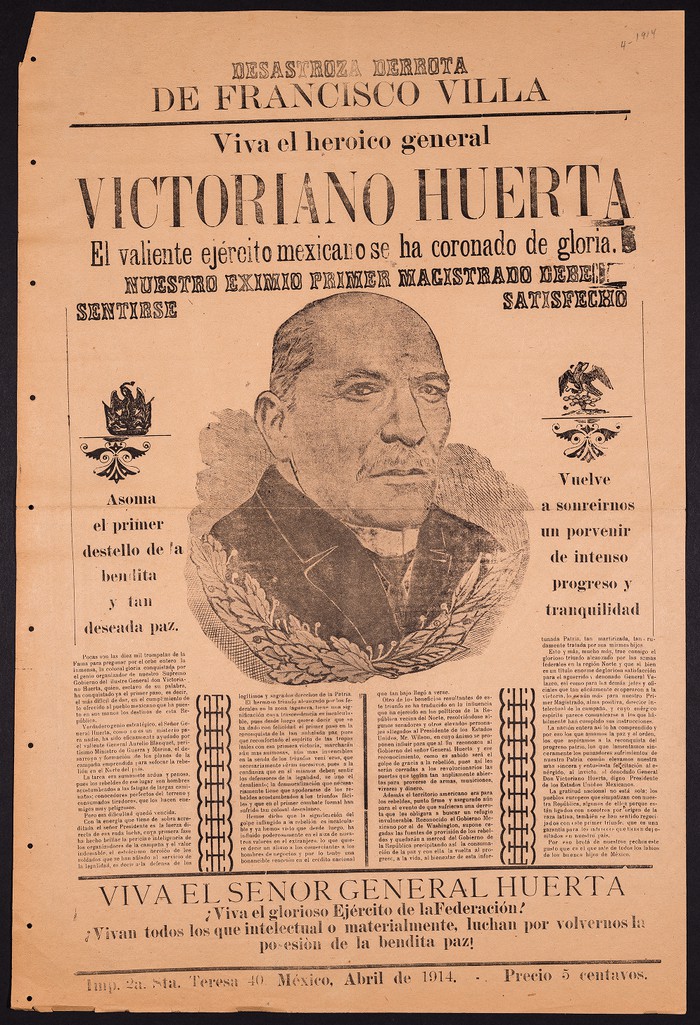

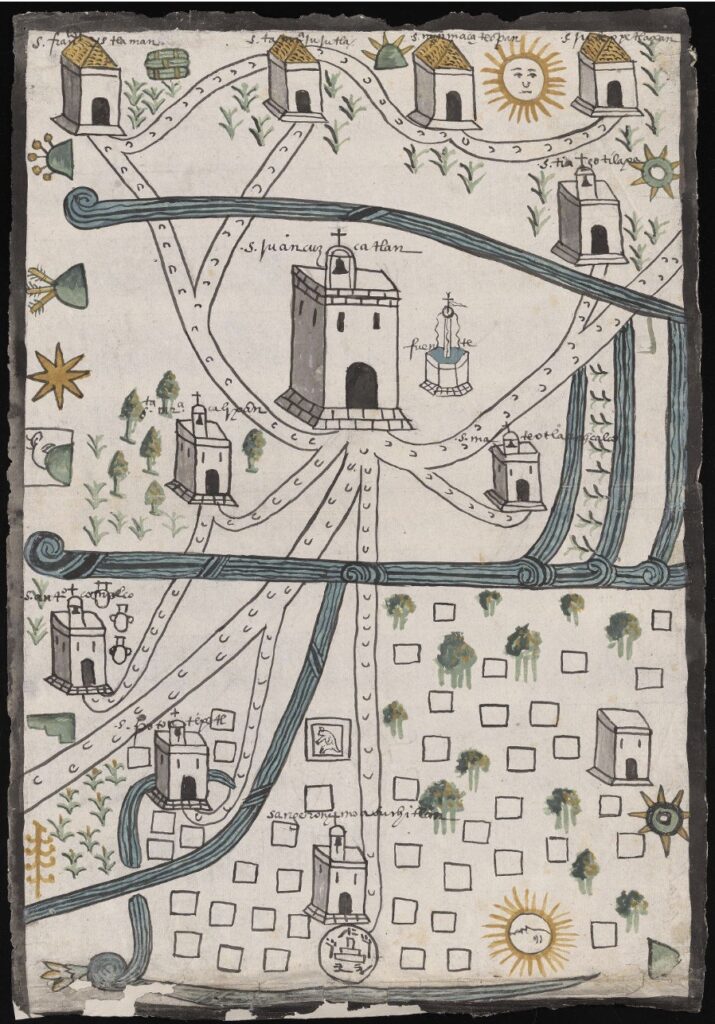

Some of our most recognizable materials are the Relaciones Geográficas, late-sixteenth-century surveys with maps that came with the Joaquin Garcia Icazbalceta purchase in 1937. The aim was for the Spanish crown to have a deeper understanding of the provinces surrounding what is today Mexico City. Were there waterways to transport goods? Mines to excavate precious gold and silver? The Relaciones have been the subject of books and digital projects, confirming their relevance for posterity.

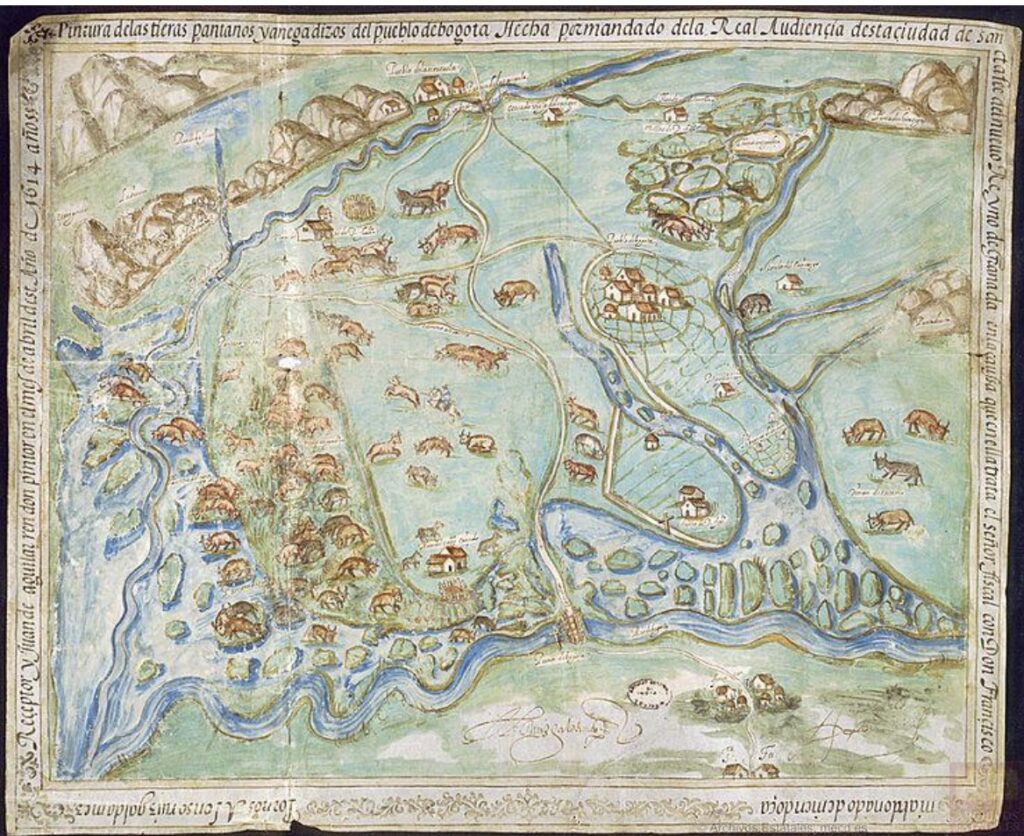

I mention the RGs, as we affectionately call them, because they came to mind when I recently viewed a 1614 painting of a Bogotá savanna in Colombia titled La Pintura de las tierras pantanos y anegadizos del pueblo de Bogotá. Like the Relaciones Geográficas, art and cartography combine in this stunning piece, which was used as evidence in a trial to determine if landowner Francisco Maldonado y Mendoza had defrauded the Spanish crown on his way to accruing vast tracts of land at cheap prices.

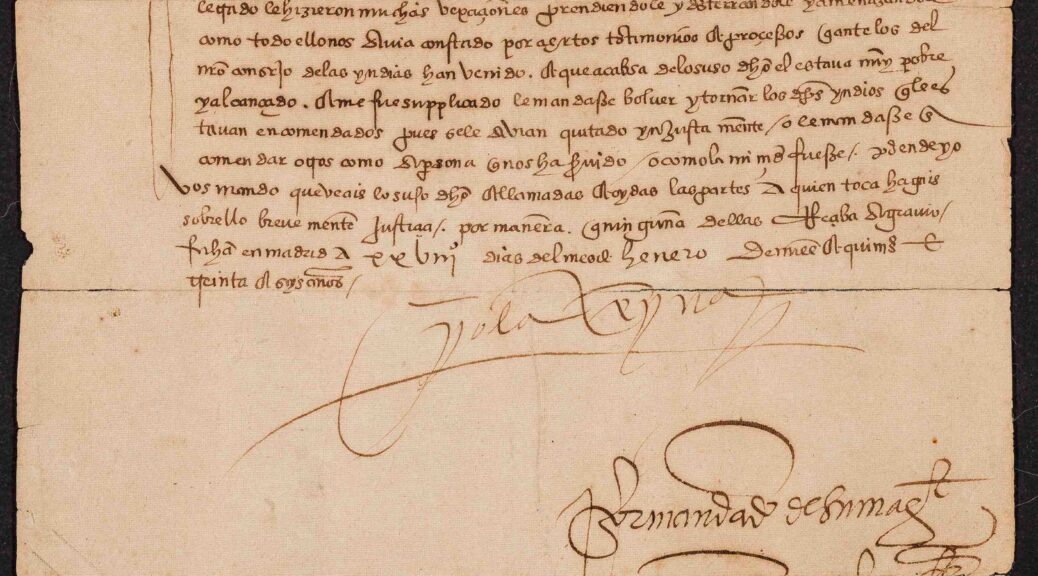

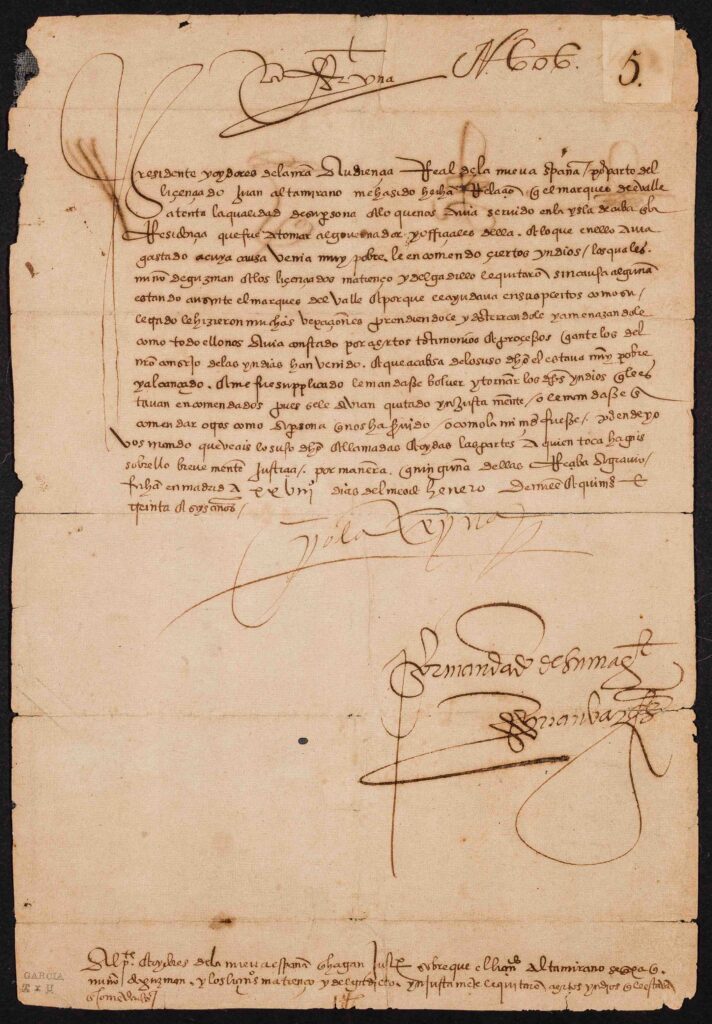

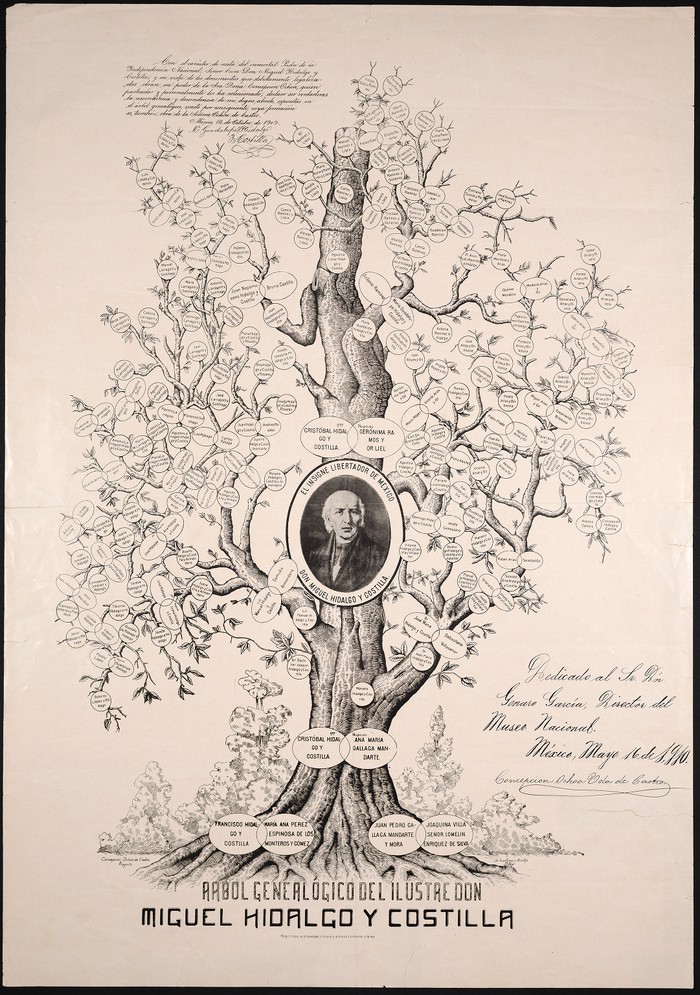

This map became the focus of a digital project called Colonial Landscapes: Redrawing Andean Territories in the Seventeenth Century, in which Dr. Santiago Muñoz Arbelaez led a team from across the Americas, including the University of Connecticut, la Universidad de los Andes, Neogranadina, and la Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia, to explore the social and political environment of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Colombia while considering land rights and Indigeneity. The project, which is available in Spanish and English, goes well beyond the digitization of one piece. In the “tour” section of the site, context is provided with the use of stunning rare materials. A portrait of Maldonado y Mendoza allows us to visualize the land baron. Other primary sources, both 2D and 3D, such as early textual and cartographic descriptions of cities and towns provided by Colombia’s national archive, are utilized to delve deeper. In the “Explore” section of the site, users can engage with different aspects of the main map in question.

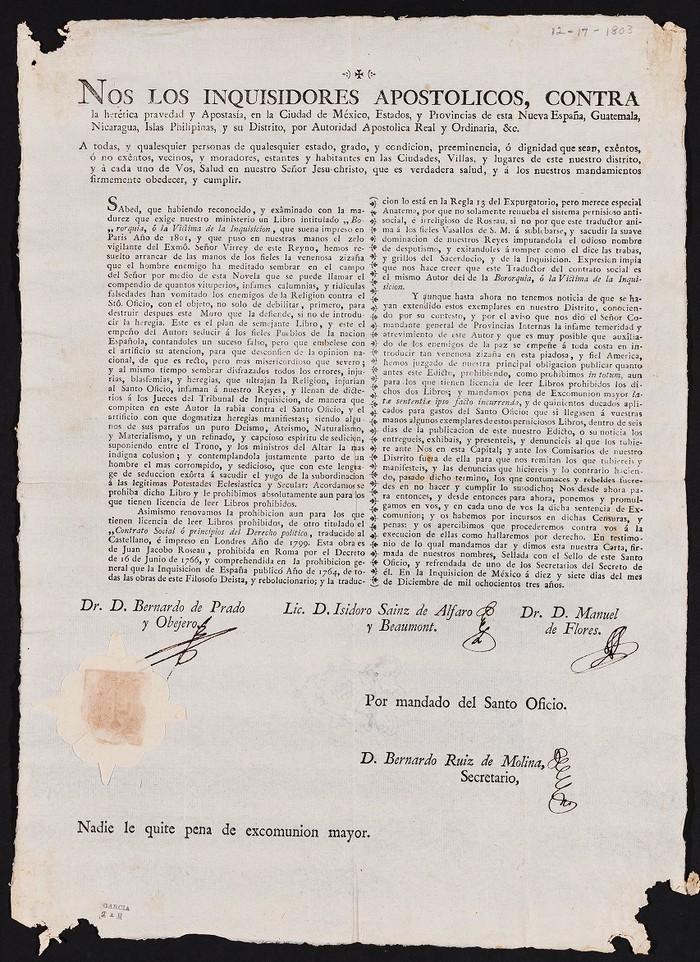

However, the highlight of this project is taking a map that discusses landownership between two European entities (Maldonado y Mendoza and the Spanish crown) and inserting Indigenous rights and notions of belonging into the matter. The Muisca are considered at length in this project as the rightful inheritors of the land. The Muisca Confederation was a group of loosely affiliated sovereign regions that made up nearly 10,000 square miles in Colombia when the Spaniards arrived.in 1499. They had the knowledge to cultivate crops in the savanna and to understand the region’s flora and fauna as well as extensive knowledge of metalworking and salt-mining. Images of Muisca ceramic figures demonstrate a rich culture whose trajectory was upended with the arrival of European colonizers. To that end, the exhibit also shows how Europeans created negative representations of the Muisca to justify the violent imposition of a new order. As land acknowledgements are negotiated and spoken in conversations emanating from sites of power, it is precisely this portion of the project that makes it so timely and necessary. Projects like Colonial Landscapes propose interesting pathways toward digital repatriation while contextualizing our understanding of the past and present.

Feature image: Relación de Atengo y Misquiahuala, 1579. Benson Latin American Collection.

Daniel Arbino is head of collection development at the Benson Latin American Collection, The University of Texas at Austin.