By Diego A. Godoy

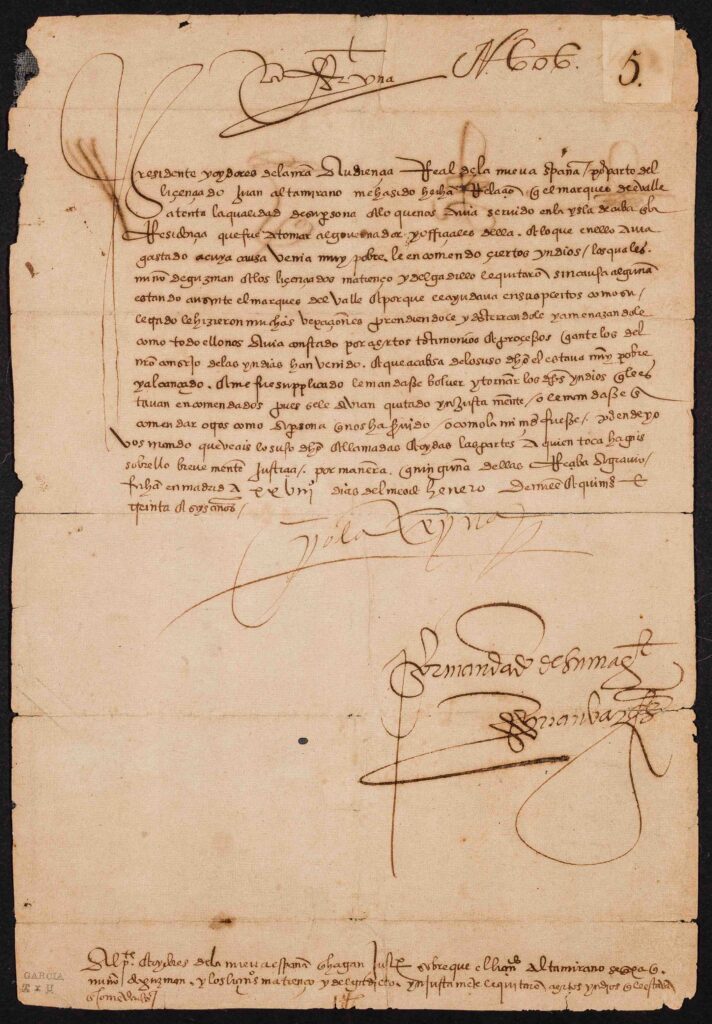

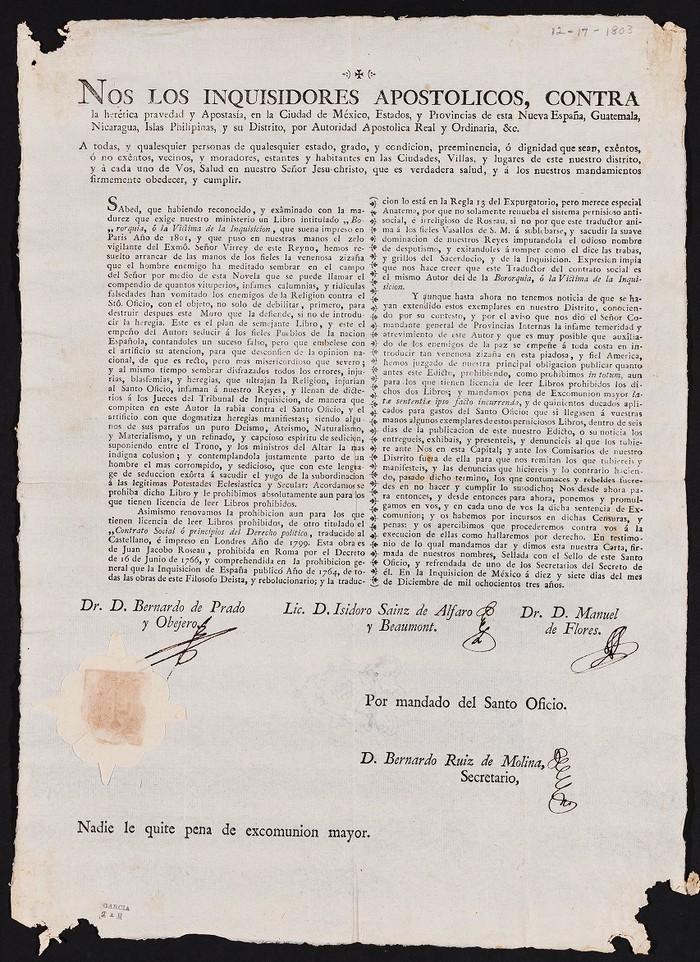

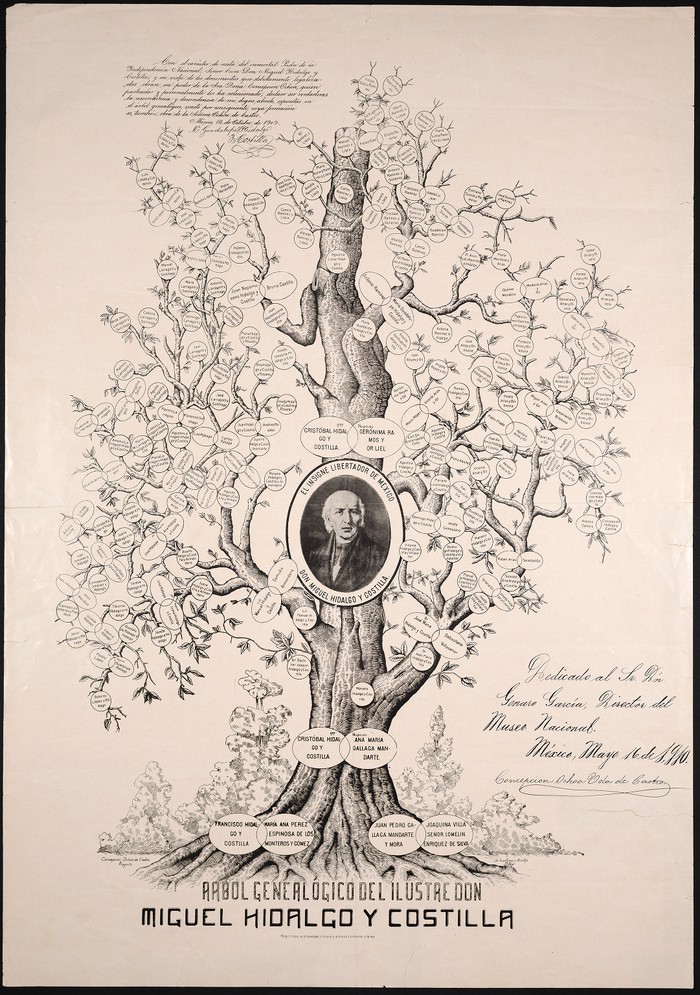

Voluminous lists of banned or redacted books, laced with sanctimonious commentary—or, early modern Spanish “cancel culture.” The illustrated family tree of a womanizing, bald curate named Miguel Hidalgo. Op-eds fawning over every viperous protagonist of the Revolution.

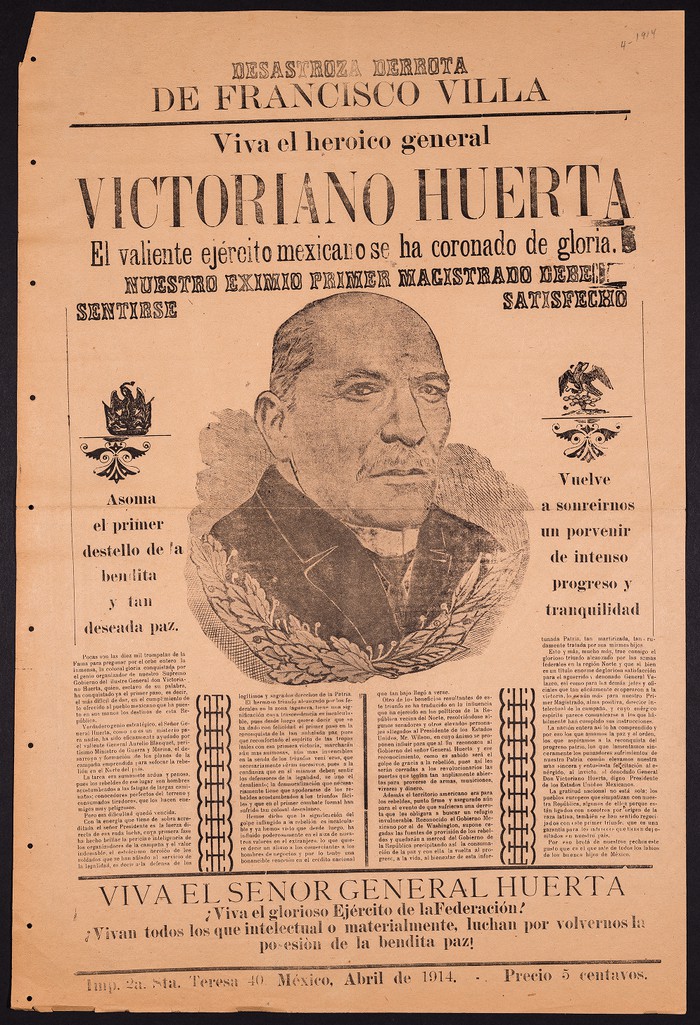

Researchers will find these items and more in the Genaro García Collection. A Zacatecan politico-cum-historian, and eventual director of Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Historia, Arqueología y Etnología, García began amassing books and other items documenting the history, culture, and politics of his country at a young age—a habit he, thankfully, never broke. In 1921, a year after his death, García’s family sold his vast treasure trove of Mexicana to the University of Texas after the Mexican government had reportedly demonstrated little interest. Seven tons of manuscripts, books, periodicals, photographs, and other printed materials made their way to Austin, becoming the seeds of what would flourish into the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection. It is one of the world’s premier archives for the Mexicophile.

Unlike many aspiring young historians, I was never a devotee of archives. I never revered the yellowed, brittle sheets of paper and the “stories” they harbored. Nothing was less appealing to me than spending the better part of a workday in some record office, wearily attempting to distill something relevant from a sea of irrelevancies, surrounded by researchers whose social ineptitude rivaled my own. I had ventured into multiple repositories and each time failed to become a convert. Perhaps this is why I gravitated toward intellectual history when it came time to find my niche. I am a believer in the book and the essay—heresy to the ears of some in the historical profession.

Then I began my position as the Castañeda Graduate Research Assistant at the Benson Latin American Collection. The job entailed creating metadata for digitized selections from the García Collection. I considered it a simple way to add some much-needed lines to my curriculum vitae, not to mention supplement my miserly graduate student salary. Yet it ended up washing away much of the aversion I felt toward archives, and introduced me to another career possibility.

After the initial new-job jitters, there was something serenely satisfying about delving into this collection. I was not a visiting researcher working against the clock to find useful bits of evidence for my own studies. I was there to calmly soak it all in, and then produce data, without any personal motive. Moreover, examining these raw materials of Mexican history proved to be a first-rate course in the subject—far more enlightening than any three-month-long seminar could ever be.

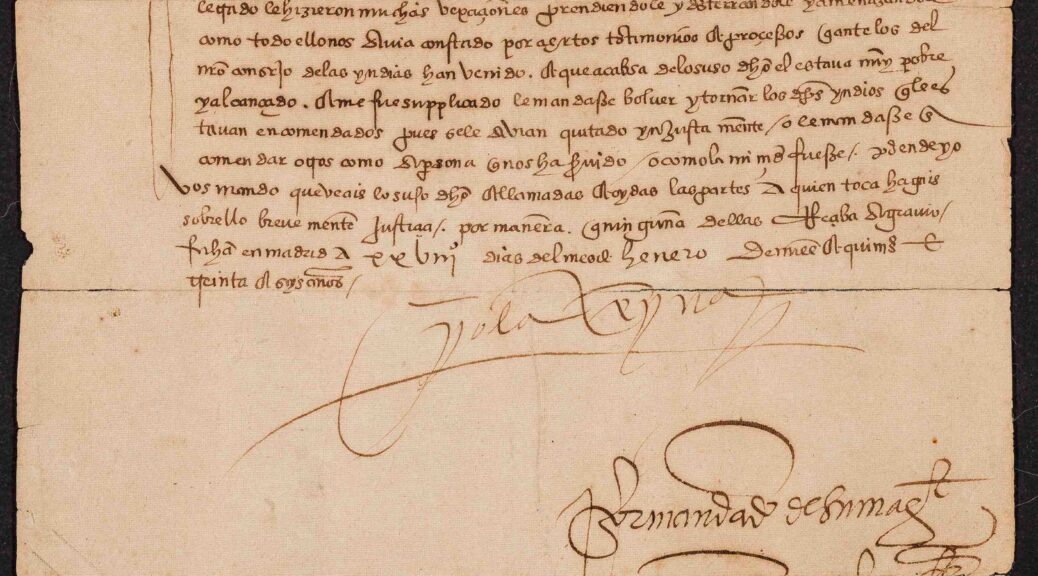

Writing metadata is, essentially, an element of the historian’s craft. One has to sit with and scrutinize an item in order to correctly interpret it. Often, this requires a healthy dose of research. Because I was not trained as a historian of colonial Latin America, documents created before the 19th century required additional research to properly contextualize them, as well as a resolute eye to decipher early-modern script. Then there is the authorial question, which occasionally demands another mini investigative journey. The end products are detailed, bilingual descriptions, and other data that, ideally, facilitate the researcher’s job.

Digitization, after all, serves to democratize research and pedagogy by making rare and remote materials easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

I began working mostly with documents dating from about 1810 to 1920. The Imprints and Images section of the García archive consists of graphic materials, such as maps, lithographs, and posters. The Broadsides and Circulars portion, on the other hand, is more textual and consists of widely distributed papers relating to Mexico’s War of Independence (1810–1821) and the Revolution (1910–1920), but is no less captivating. These approximately 1,200 items are now viewable on the collections portal, and materials from the photographs, archives and manuscripts, and rare books parts of the collection are continually being uploaded.

Currently on my docket are digitized selections from Archives and Manuscripts. This section contains individual historical manuscripts from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Those from the 1500s have proven to be the most challenging, not only due to my lack of paleography skills but also my unfamiliarity with early-modern Spanish grammar. But a fair share of focus and tenacity goes a long way. The “Archives” portion holds the papers of several prominent 19th-century characters, such as Lucas Alamán, the conservative statesman and intellectual, and Antonio López de Santa Anna, the peg-legged vendor of national territory. It will be a welcome break from my travails through the colonial era.

I am glad to play a pivotal role in the Benson’s initiatives to develop its digital collections. Digitization, after all, serves to democratize research and pedagogy by making rare and remote materials easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Now, scholars unable to jet off to Austin from, say, Genaro García’s home country of Mexico, can consult his collection from their laptops. Digital content also allows for innovative exhibition practices, like online showcases with interactive features. And perhaps most importantly, digitization safeguards our cultural heritage by producing a virtual “backup.”

The digitization and metadata creation for the Images and Imprints and Broadsides and Circulars materials were generously funded by the Latin Americanist Research Resources Project (LARRP), Center for Research Libraries, with additional funds provided in honor of Consuelo Castañeda Artaza and her sons. Of course, none of this could have been accomplished without the dedication of several Benson employees. David Bliss, Itza Carbajal, Robert Esparza, Mirko Hanke, Dylan Joy, Ryan Lynch, Madeleine Olson, and Theresa Polk all made indispensable contributions to the digitization and publication of these items.

It has been over two years since I began this position. I am still a devout fan of books and other easily available, published sources. But I am no longer agnostic about the pleasures of archives, at least not the one described here.

Diego A. Godoy is a PhD candidate in Latin American history at The University of Texas at Austin and Castañeda Graduate Research Assistant at the Benson Latin American Collection. Before coming to Texas, he earned an MA in history from Claremont Graduate University. He is broadly interested in the intellectual and cultural history of the region. His particular focus is on the history of criminology, detection, and crime writing. He is author, most recently, of the article “Inside the Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema,” which appeared in the fall 2020 issue of Portal magazine.