“Who does not have etched in the mind images of countries and of the world based on maps?”

– John Noble Wilford, The Mapmakers

It’s certainly the case that our perception of the world’s geography is rooted in our experience with the maps we’ve encountered, developed and designed over eons by both hand and machine. Even though we may have become increasingly reliant on disembodied voices to lead us where we need to go, the archetype for understanding the concept of location which we carry in our minds was instilled by the road guides of family vacations, massive retractable world maps of the elementary classroom and spinning globes of our past.

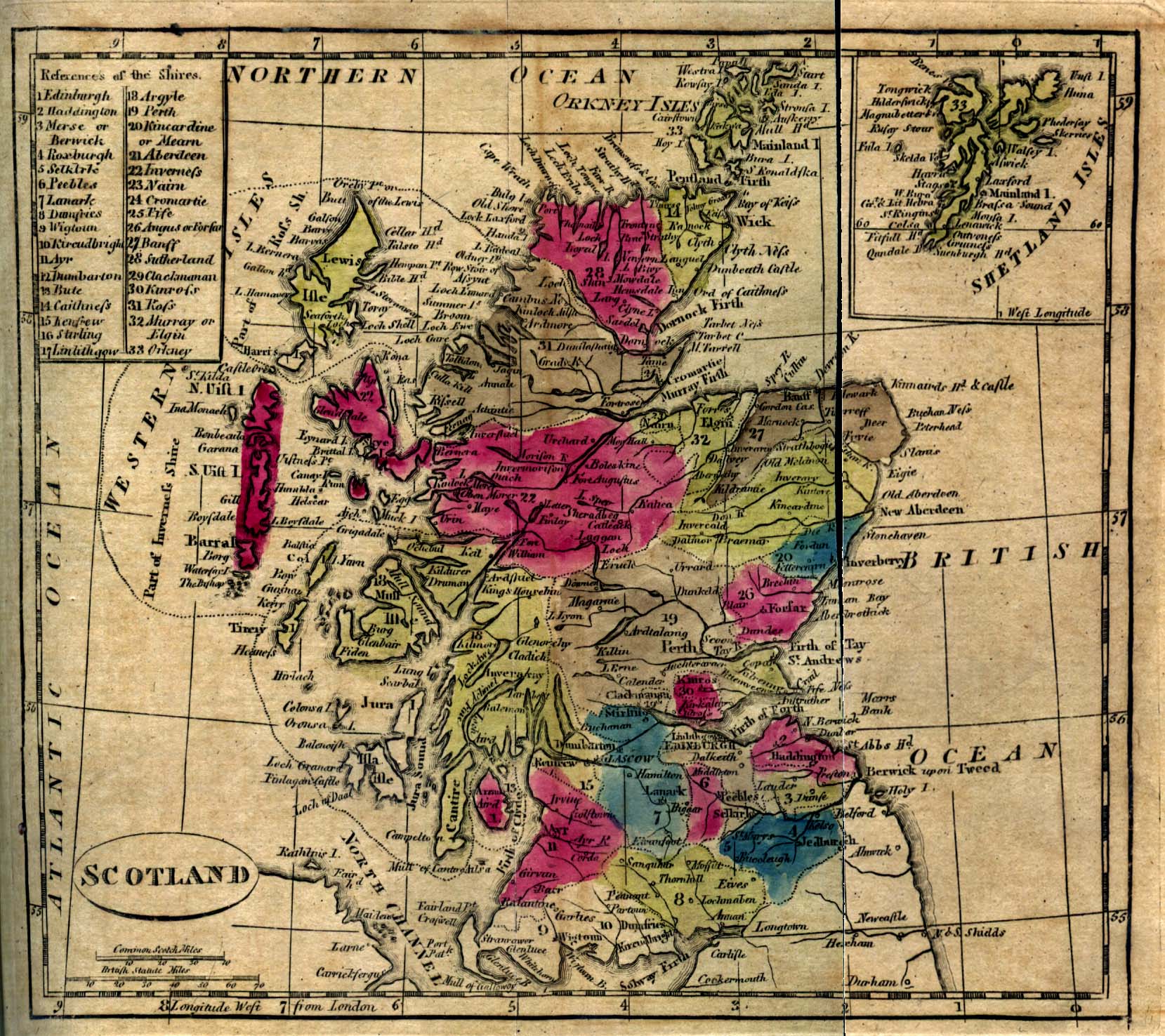

Equal parts art and science, maps are one of the most effective methods for conveying information visually in virtually any field of inquiry. In the miniaturization of space that is necessary to explain vast areas on a personal scale is a documentation of history and of change; of character and personality, value and values; of plant and animal; of health and illness, feast and famine; of motion and stasis; and of nearly any aspect of life and place that can be categorized for better understanding the world in which we live.

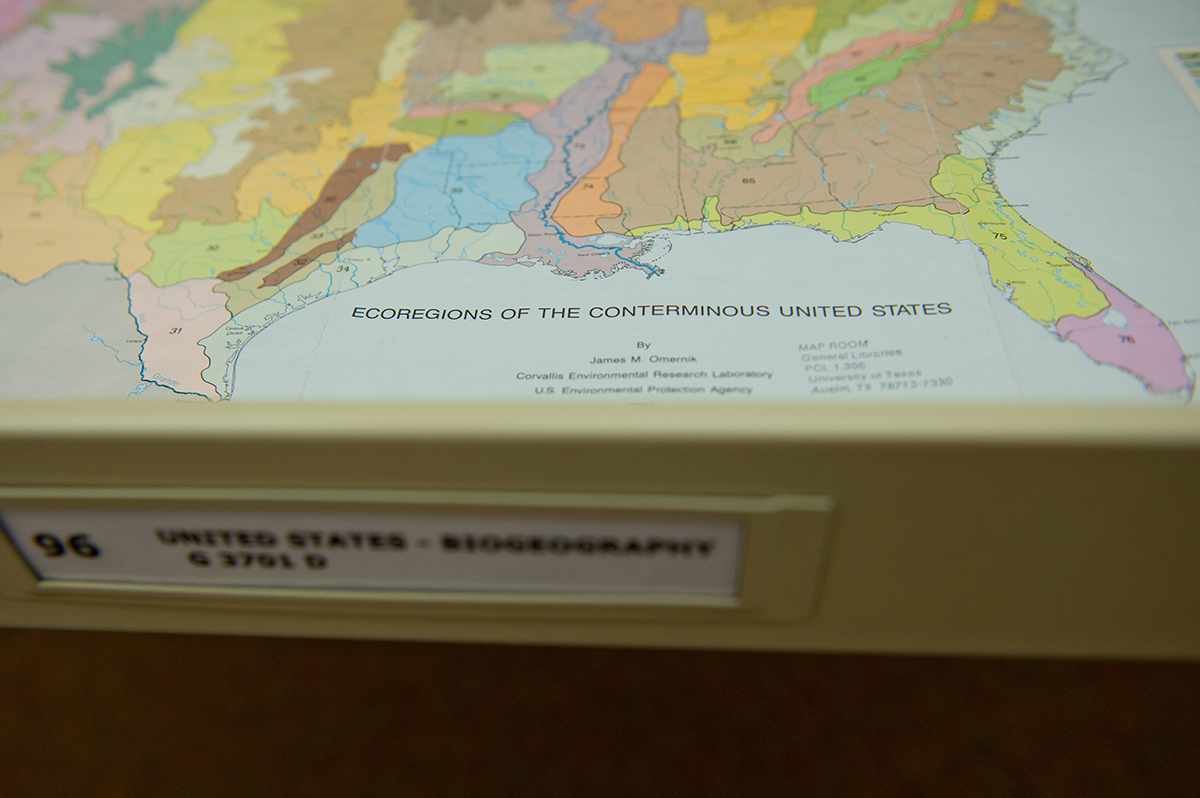

And that, perhaps, is what makes the map collection at the Perry-Castañeda Library so incredibly valuable. Its scope in both size and subject is immense enough to maintain an intrinsic value — both as historical artifact and as a tool of modern research and reference — that goes unaffected by the passage of time.

Though the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection is considered a general collection, it’s anything but. Residing on the first floor of the university’s flagship library, it features more than 250,000 cartographic items representing all areas of the world. And its online component is not only one of the most highly visited websites at the university — garnering nearly 8 million visits annually — but is in the top ten most popular results for a Google search of “maps.”

The university began informally collecting maps previously — at the General Libraries, but also through efforts at the Geology Library, the Barker Texas History Center and the Benson Latin American Collection — but it wasn’t until the PCL opened in 1977 that the Map Collection was established on the first floor of the building as an independent collection.

The core of the collection emerged with the acquisition of the U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps, which date from the late 19th century and cover the entire United States, U.S. territories and other parts of the world where governments contracted U.S.G.S. for mapping, such as Saudi Arabia.

Since then, the collection has grown to feature military maps from various conflicts around the world, government nautical and aeronautical charts, topographic collections, city maps representing over 5,000 cities around the world, aerospace navigation charts, data and demographic maps, and just about every other conceivable type of physical cartography.

The collection also houses an extensive collection of atlases, from a street atlas of El Paso to the National Atlas of India. The library also purchases commercial and foreign government-issued topographic map series, country, city and thematic maps. The collection also includes a small but popular collection of plastic raised-relief maps and globes, not only of earth, but of the Moon, planets and other various celestial bodies.

Most of the maps in the collection date from 1900 to the present, and the collection is constantly being updated with newer materials, and complements a number of significant historical map collections housed on campus in the Center for American History (historical maps of Texas), the Benson Latin American Collection, the Harry Ransom Center and the Walter Geology Library.

Paul Rascoe — the Libraries’ Documents, Maps, & Electronic Info Services Librarian — has been the driving force behind the collection at PCL, especially in the formulation and execution of the collection’s online component. And it hasn’t hurt to have the planets align, at times.

“In 1994, we decided that we were going to scan maps,” says Rascoe. “We had a Macintosh computer and a Mac scanner, which I believe cost $100. We had a plan to put them in sort of a web menuing system called Gopher, but fortunately, simultaneously with our wanting to put maps online, the first web browser was introduced in that year.”

Fortuity aside, the decision of which maps to begin the scanning project with stirred up interest in digital access from an unexpected party. Rascoe started with some pretty rudimentary maps from the Central Intelligence Agency, which made sense given the storage limitations at the time.

“The CIA called me and asked, ‘How do you get our maps to look so good online?’,” relates Rascoe. “So I put my student assistant on the phone to give them some photo editing techniques, which is unusual because they create born-digital at CIA. But they’ve come a long way…we’ve all come a long way since then.”

To date, more than 70,000 maps from the printed collections have been scanned and added to the digital side of the PCL Map Collection, providing access to a vital resource not just to the university community, but to a global audience. And Rascoe says that more maps were scanned last year than in all previous years combined, so there’s both a will and a mechanism to expand access to the collection.

One of the benefits the PCL Map Collection has over other collections of the sort is being collocated within a top-ten research library where thousands of additional maps reside in books and journals as fold-outs and plates that are easily accessible and duplicable.

“We’ve been able able to go through our government documents and our impressive book collection in the library, actively looking for public domain maps that are hidden in books,” explains Rascoe. “One of the things that Google Books can’t do is scan folding maps in a book. But we can do that.”

“We’ve discovered a lot of things over these many years with the staff going through our collections, so we’ve leveraged the collections to get content up online. And now you can find it in Google, so we’ve made discovery easy.”

A wide variety of customers use the collection: faculty researchers; students planning canoe trips; engineering firms working on impact statements; hobbyist genealogists searching for the location of long-forgotten historical places; and by environmental consultants, developers or property owners who may be interested in all editions of maps for potential property development uses.

The map collection is widely used by students, faculty and people of all stripes to fortify research, as well as for use in discovery and as tools for teaching or learning. And the maps inhabit a vital space within such a myriad of disciplines that an institution desiring to have comprehensive resources to support its research must assume maintenance of a vast collection of cartographic materials spanning a vast reach of time.

“Every type of map has its own value,” says Rascoe. “We have research on campus covering all parts of the world, so our community uses every area of the collection.”

“Every type of map has its own value,” says Rascoe. “We have research on campus covering all parts of the world, so our community uses every area of the collection.”

Despite the expansion of maps made available by the evolution of the internet, the collection still receives fairly regular inquiries from media organizations, especially during times of political upheaval or natural disaster, both of which can strike unassuming regions that may not be familiar to American news consumers.

Katherine Strickland, who manages the PCL Map Collection, provides a recent example. “In 2014, when Crimea was voting on the independence referendum, I received calls from both CNN and the PBS NewsHour,” says Strickland. “I didn’t have exactly what CNN wanted, but we did find certain items that the NewsHour could use.”

Rascoe supposes that the dissolution of traditional media by the internet may be subtly benefiting collection usage. “There are only a few newspapers now that have a cartographer on staff,” says Rascoe. “But they certainly use our maps as background for making new maps, and we want people to use them.”

The collection also serves as a resource for high-level non-academic and humanitarian use, as well. The maps have been used for United Nations investigations, and by numerous non-governmental aid organizations.

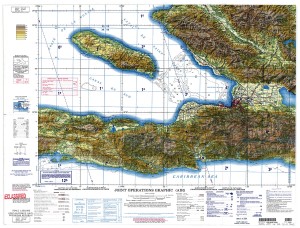

“After the earthquake in Haiti a few years back we were able to put up a set of detailed topographic maps of Haiti right away,” says Rascoe. “It happens at times in the rush to respond to disaster that sometimes resources are either in short supply or overlooked, and in that case, we’ve provided much needed access. We have a lot of contact from the military thanking us for making the resources available and easily accessible.”

Because the online resources in the PCL Map Collection are also largely in the public domain, the site has become a ready resource for authors, artists, designers and production companies who need supplemental or decorative design elements for their respective work. In the last few years, Strickland and Rascoe have fielded inquiries from representatives from TV shows like NCIS (CBS), Homeland (Showtime) and Matador (El Rey) wishing to use maps found in the online collection as elements of production design, and its maps are regularly requested for publication in books or for documentary use.

Whatever the developments in technology, it seems that the PCL Map Collection will continue to grow apace as long as it maintains such a broad and far-reaching patronage that is thoroughly engaged with this valuable resource.

“We have a lot of requests for maps,” says Rascoe. “We have a pretty good idea of what people want, and they’re all over the map.”

To help grow the PCL Map Collection and keep it available for study worldwide, click here to make a contribution.