Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this new series, librarians from UTL’s Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

Over the years of my involvement in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (MEIS), I have become something of an advocate for learning modern Turkish. The necessity of facility with Turkish in order to conduct research in MEIS, and more importantly, to carry on scholarly communication in MEIS, grows clearer every year. I would not hesitate to argue that non-Turkish scholars ignore Turkish scholarship at their own peril—it is that central, plentiful, and informative. An excellent example of a scholarly development out of Turkish academe that would be quite useful for MEIS pedagogy and research is İslam Düşünce Atlası, or The Atlas of Islamic Thought. It also happens to be an incredible digital Islamic Studies scholarship initiative.

İslam Düşünce Atlası (İDA) is a project of the İlim Etüdler Derneği (İLEM)/Scientific Studies Association with the support of the Konya Metropolitan Municipality Culture Office. It is coordinated by İbrahim Halil Üçer, with the support of over a hundred researchers, design experts, software developers, and GIS/map experts. The goal of the project is to make the academic study of the history of Islamic thought easily accessible to scholars and laypeople alike through new (digital) techniques and within the logic of network relations. İDA has been conceived as an open-access website with interactive programs for a range of applications. Its developers intend it to contribute a digital perspective to historical writing on Islam: a reading of the history of Islamic thought from a digitally-visualized time-spatial perspective and context.

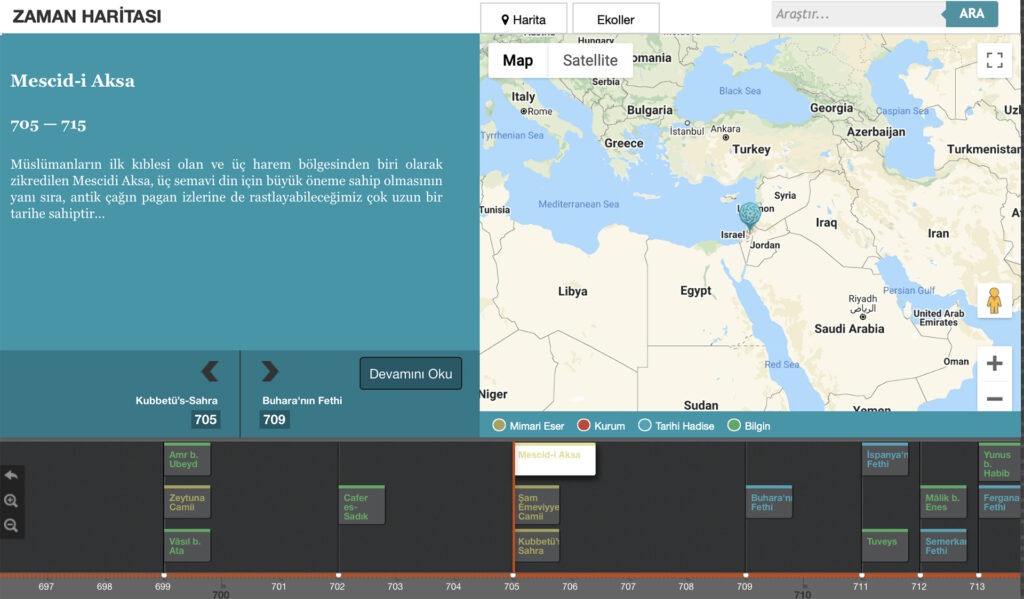

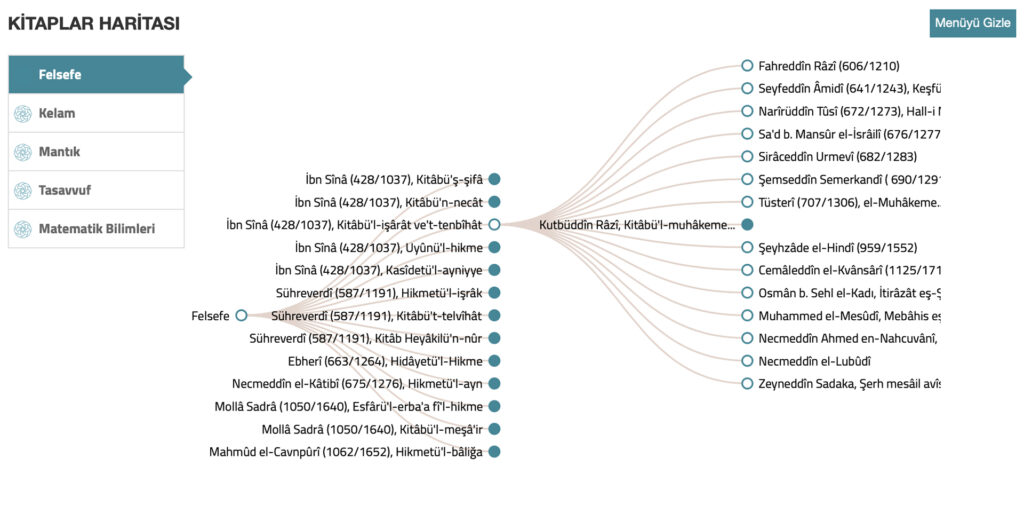

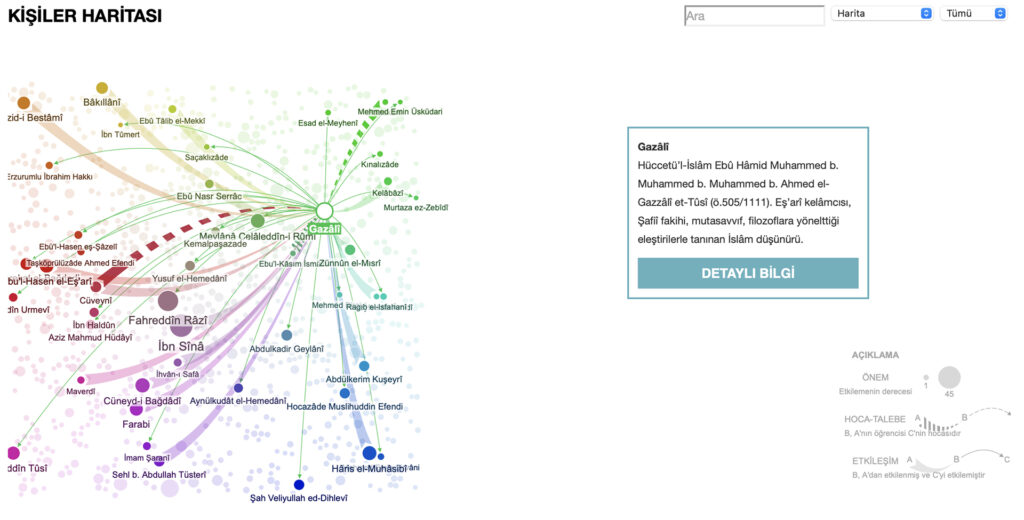

İDA features three conceptual maps that aim to visualize complex relationships and to establish a historical backbone for the larger project of the atlas: the Timeline (literally time “map,” which is a more signifying term for the tool, Zaman Haritası), the Books Map (Kitaplar Haritası), and the Person Map (Kişiler Haritası). It also proposes a new understanding of the periodization of Islamic history based on the development of schools of thought (broadly defined) and their geographic spread. İDA endeavors to answer several questions through these tools: by whom, when, where, how, in relation to which school traditions, through what kinds of interactions, and through which textual traditions was Islamic thought produced? Many of these questions can be summed up under the umbrella of prosopography, and in that arena, İDA has a few notable peer projects: the Mamluk Prosopography Project, Prosopographical Database for Indic Texts (PANDiT), and the Jerusalem Prosopography Project (with a focus on the period of Mongol rule), among others.

One of my favorite aspects of İDA is the book map and its accompanying introduction. The researchers behind İDA do their audience the great service of explaining the development and establishment of the various genres of writing in the Islamic sciences. Importantly, they also link the development of these genres to the periodization of Islamic history that they propose. The eight stages of genre development that are identified—collation/organization, translation, structured prose, commentary, gloss, annotation, evaluative or dialogic commentary, and excerpts/summaries—share with the larger İDA project their origin in scholarly networking and relationship building. By visualizing the networks of Muslim scholars, as well as the relationships among their scholarly production and the non-linear, multi-faceted time “map” of Islamic thought, İDA weaves together the disparate facets of a complex and oft willfully misunderstood intellectual tradition

I encourage readers not only to learn some modern Turkish in order to make full use of İDA (although Google translate will work in a pinch!), but also to explore threads throughout all of the visualizations: for example, trace al-Ghazālī’s scholarly network, and then look at that of his works. What similarities and differences do you notice? Is there a pattern to the links among works and scholars? Readers who are interested in the intellectual history of Islam should check out my Islamic Studies LibGuide, as well as searches in the UT Libraries’ catalog for some of their favorite authors (see here for al-Ghazālī/Ghazzālī, Ibn Sina/Avicenna, and Ibn al-Arabi).