Throughout the fall of 2018, I was honored to be able to convene UT South Asia Institute’s Seminar Series, “Popular | Public | Pulp: form and genre in South Asian cultural production.” Throughout the series, speakers explored printed examples of South Asian popular culture—mysteries, romances, comics—as they underscore and grapple with historical and contemporary concerns such as identity, power, & representation. In addition to interrogating literary approaches, speakers in the series further addressed questions of gender, of sexuality, of caste & religion, and of authority, helping readers and scholars alike challenge what qualifies as “worthy” both in terms of style and substance.

One goal of the series was to draw attention to UT Libraries growing collection of popular and pulp fiction in South Asian languages, a collection that is nationally and internationally unique in gathering and preserving popular materials and subsequently making them available for users. Beyond publicity, however, the series was also intended to uncover reading and distribution networks for these materials so that I might continue to creatively and productively acquire them while on acquisitions and networking trips to South Asia. In November and December, and with the generous funding of both UTL and the South Asia Institute, I was privileged to travel to India and more deeply explore a venue repeatedly invoked in the fall speaker series: small lending libraries.

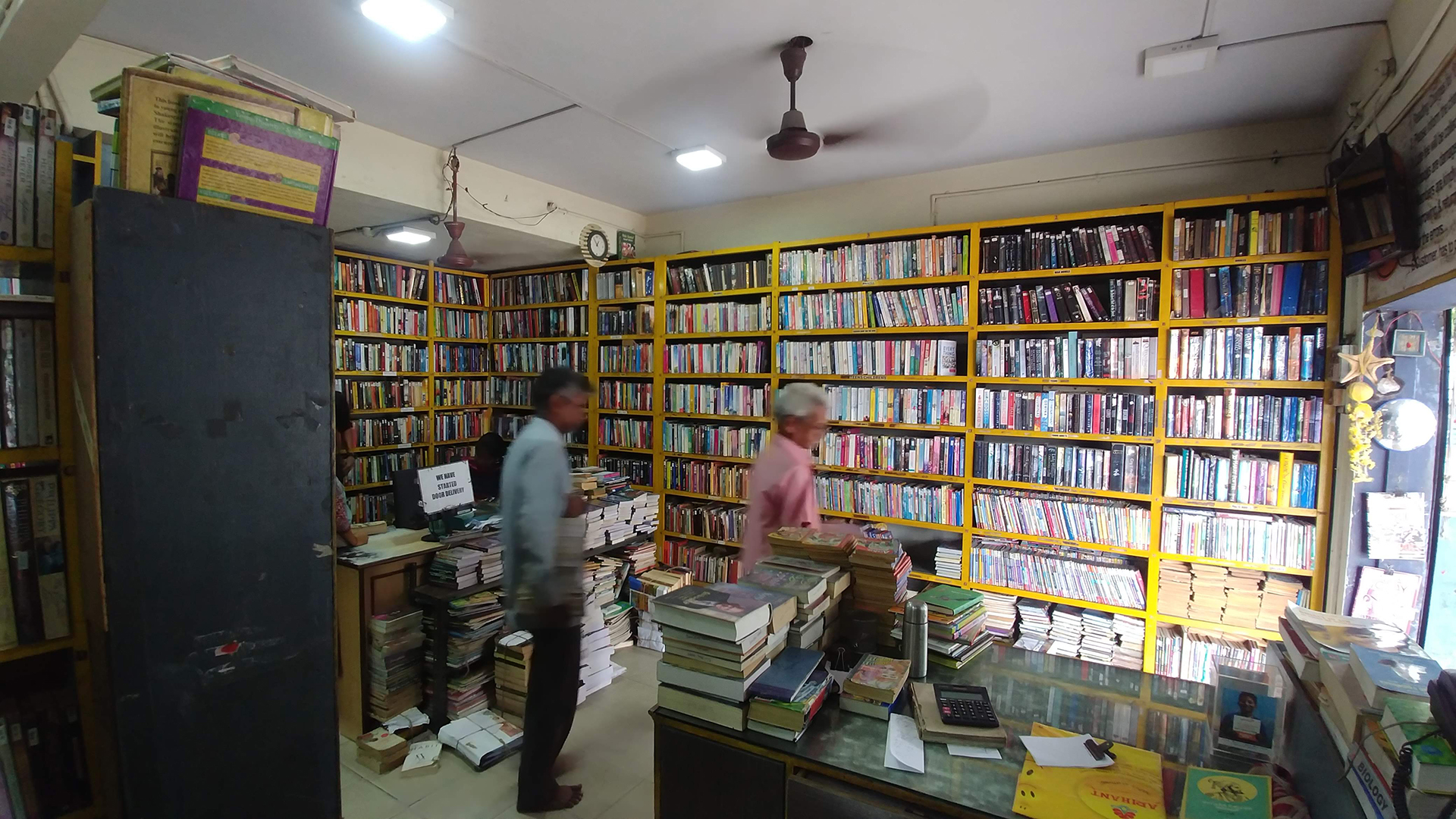

Small lending libraries are a cultural phenomenon throughout South Asia which support themselves through highly localized, neighborhood-based memberships. Unlike UT Libraries which has a long-term and “long-tail” research agenda, the mission of these lending libraries is to support current and highly popular reading practices, not unlike many small public libraries in the U.S.

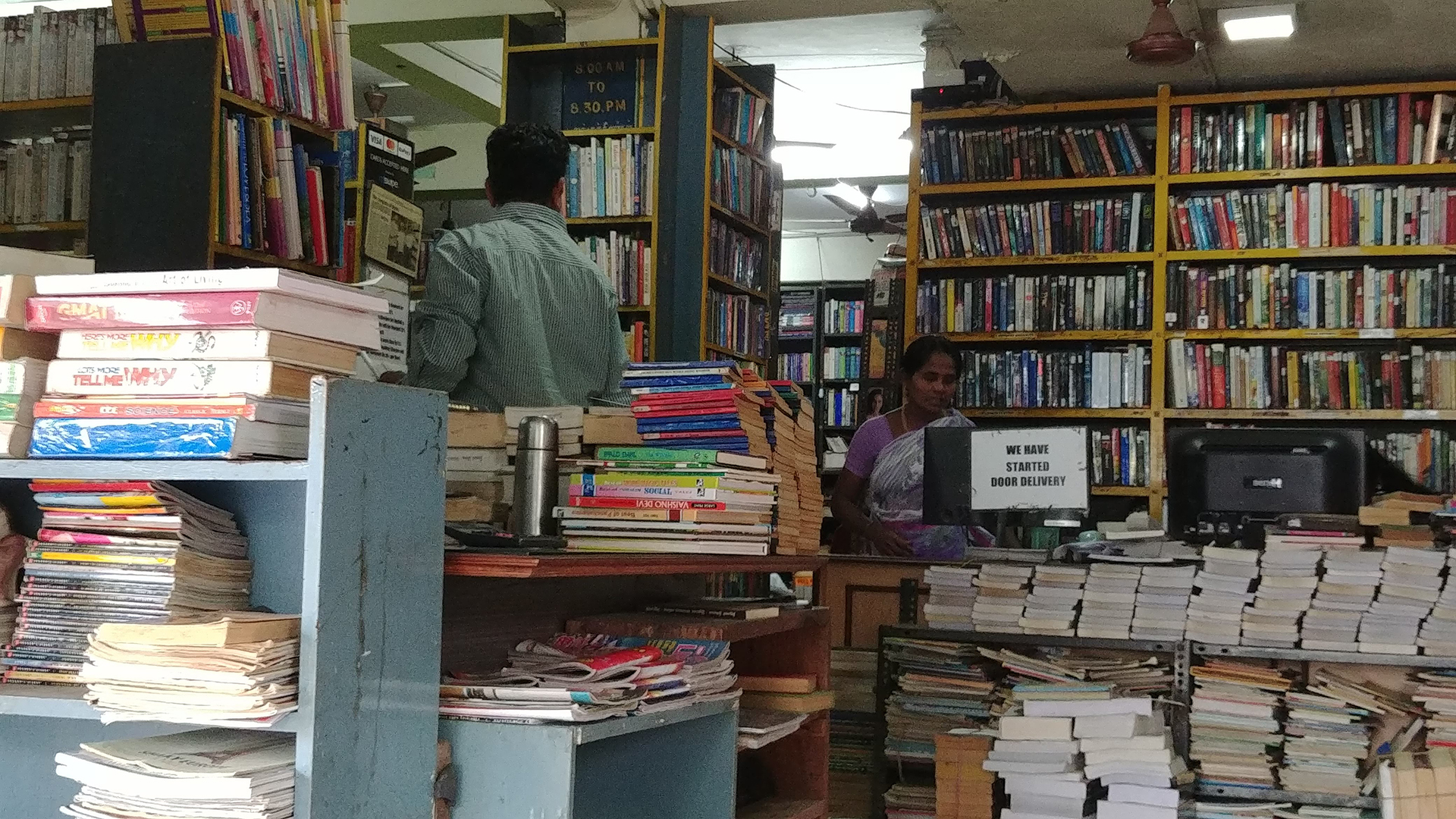

While in Chennai, I was able to visit two lively lending libraries—Easwari and Senthil—to observe their operations, to ask questions about the popularity of particular authors, and to acquire second-hand materials. Both libraries carry all the bestsellers—in English [Mills and Boon, Harry Potter, James Patterson] and in Tamil [Rajesh Kumar, Indira Soundarajan, Raminichandran]—and experience high circulation of their books. Because preservation is not part of their mission, the libraries are willing to sell the most ephemeral of their materials, namely monthly periodicals which include crime, detective and “women’s” fiction (romances as well as family dramas).

Despite the vibrant activity I observed at both these libraries, I am told that lending libraries are slowly vanishing from the South Asian landscape, ceding space to other entertainments and ways of “time pass.” I was happy to have had the chance to visit these libraries and I do hope they will still be open and serving their readers on my next visit. If not, though, I am comforted knowing that UT Libraries is participating in documenting and preserving some of this literary and cultural history for researchers long into the future.