Next year, I’ll have been a librarian for 10 years, and there are many things that I’ve come to learn and appreciate in my time in the profession. I’m a subject specialist, the liaison librarian for Middle Eastern Studies at UT Austin. I manage library services for researchers interested in the Middle East as well as collections from or about the Middle East. I also coordinate services and collections for the History department. Both roles have allowed me to consider and question the boundaries that researchers and librarians alike have maintained regarding the types, priority, and value of library collections, particularly our physical collections. While all cultural heritage has value, it is usually what we call special collections or rare books that are the most highly prized. They tend to cost more, there are fewer of them, and they require special handling because of their age and/or material. Special collections are often stored in a separate and distinct space, served by dedicated and highly trained personnel, and permitted for use in controlled circumstances. What happens, however, when a valuable, rare item is kept in the regular stacks of the library’s general collections? How did it get there and why would a librarian keep it there? I want to explore these questions with two examples from the Middle East collections at UT Libraries that have allowed me to design new approaches to teaching and learning with the special collections in our stacks.

Locating Egypt in Türkiye

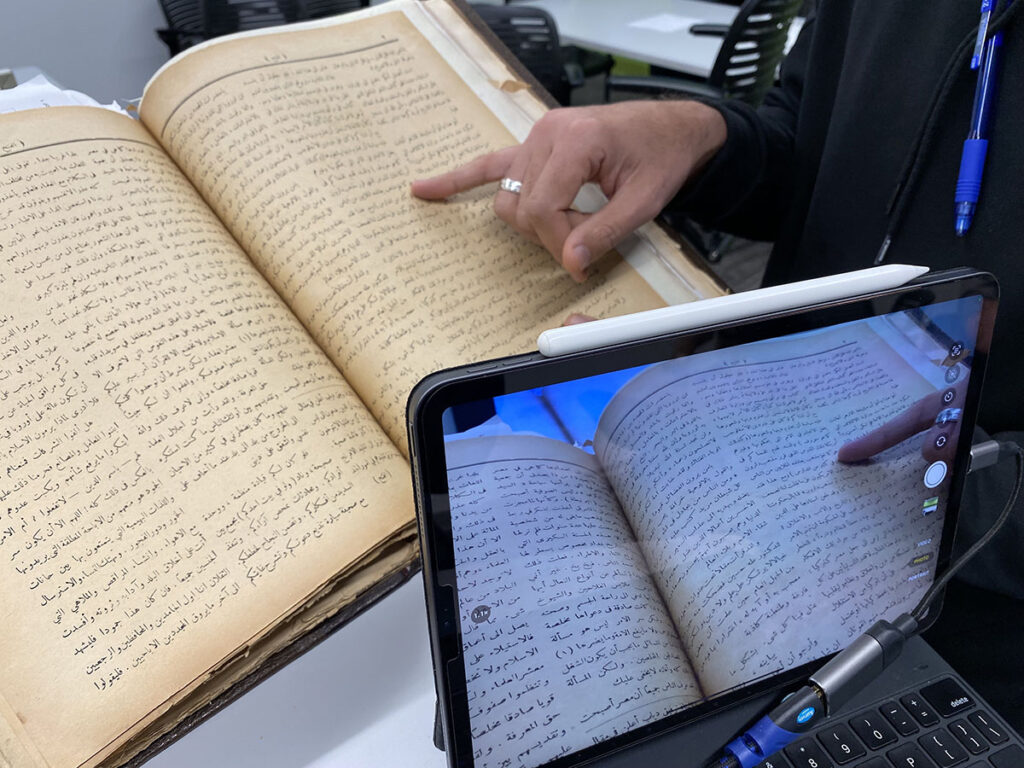

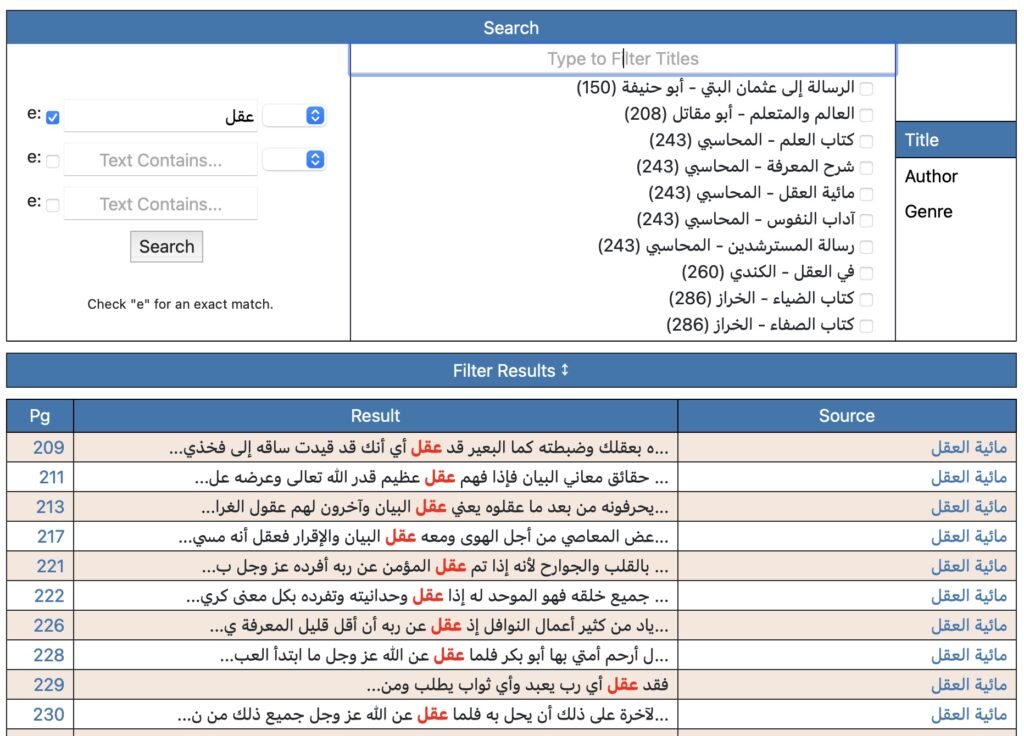

In summer 2022, I had the honor to represent UT Libraries on an acquisitions and networking trip in Istanbul and Ankara, Türkiye. I met with a private collector in Istanbul, to whom I had been introduced by one of our regular Türkiye vendors, and purchased a number of titles in Arabic that had been published in Egypt. (It is perhaps curious that I’d go looking for Arabic in a country where the principal language in Turkish, and I’ve written about how and why I do this here.) One of those titles was al-Fath: Sahifah Islamiyah ‘Ilmiyah Akhlaqiyah, an intellectual journal circulated in the early 20th century. This journal is a crucial, backbone source for the intellectual, political, and legal history of the Middle East. It covers a variety of topics, including modernist Islamic thought, modern Egyptian history, Arabic language, British colonial history, Palestine and Zionism, Ottoman history, ethics, and the moral landscape of early 20th century Egypt. It is often cited by intellectuals of its time period (indicating its contemporary import), but it’s not widely available for research consultation in North America . Although North American scholars—including several at UT Austin in the departments of Middle Eastern Studies and History––have seen this title cited, and desired to consult the periodical themselves, many have been unable to do so. Only three North American institutions, including UT Austin, can claim to have a complete copy, while a handful of others have some volumes but not others. Considering the journal was published from 1926 – 1948, such spotty coverage is often inevitable. Additionally, al-Fath has not been digitized (which runs contrary to the growing researcher expectation for the digital availability of such essential materials).

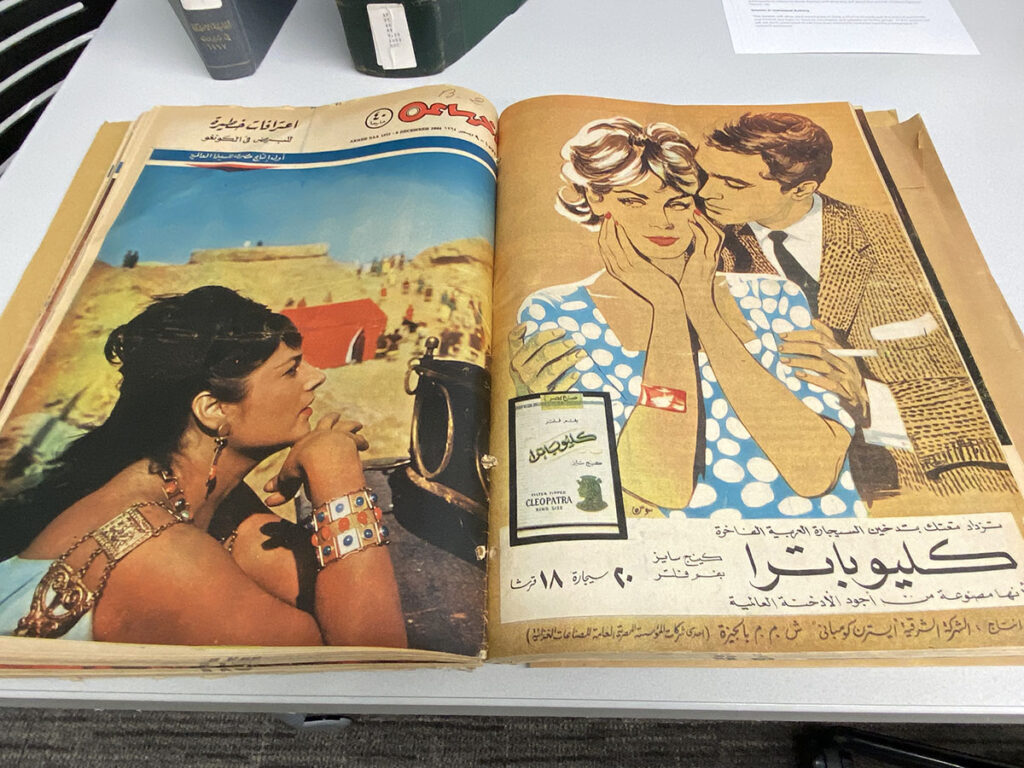

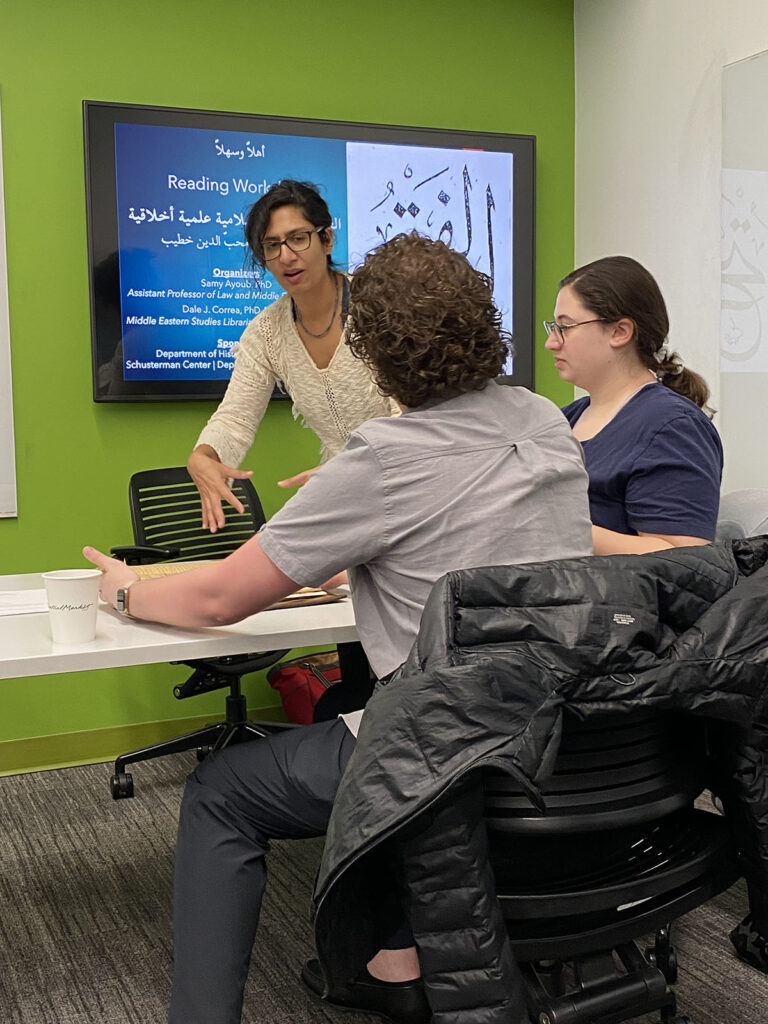

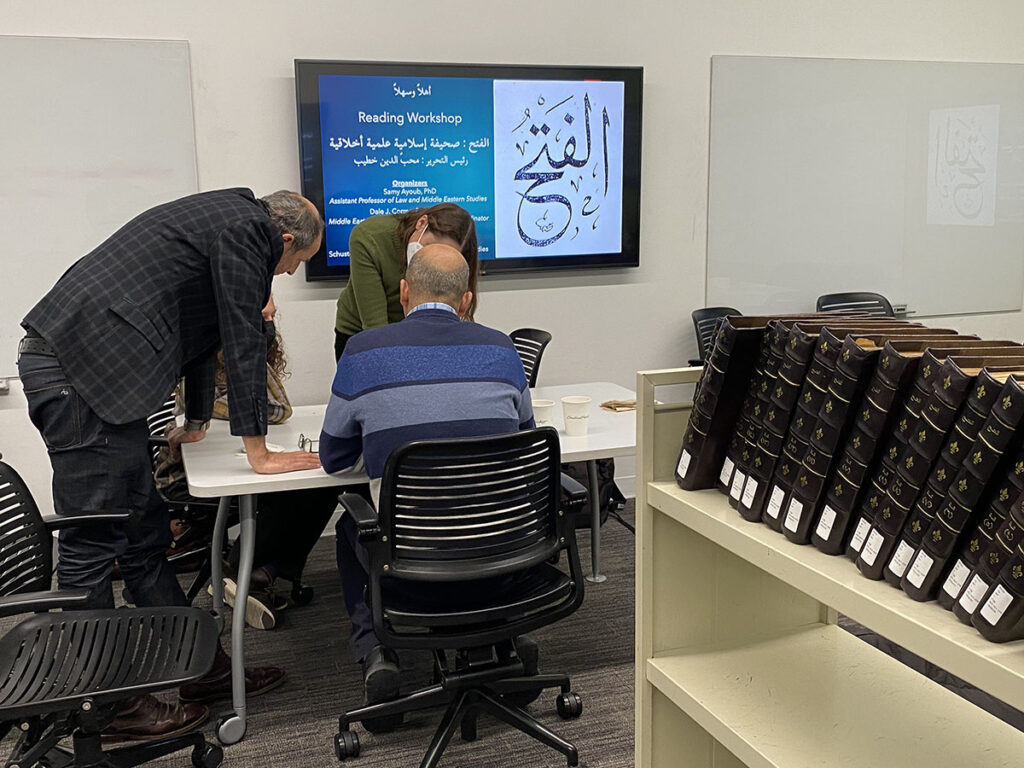

When I brought al-Fath to the UT Libraries, I knew there would be a significant community of interest around it and that it would be an ideal locus for scholarly exchange. I partnered with Dr. Samy Ayoub (Department of Middle Eastern Studies and the UT School of Law) to prepare and host a reading workshop on al-Fath for faculty and graduate students in January 2023. Over the course of the fall semester, the UT Libraries’ Content Management department was able to complete the description and processing of al-Fath, getting it into the stacks in record time for researchers. This gave Dr. Ayoub and me time to prepare for the workshop with the help of Dr. Ahmad Agbaria (the Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies), who specializes in 20th century Arab intellectualism. While these two faculty members selected passages and legal cases for workshop attendees to read and interpret, I prepared a display of contemporary periodicals from our collections to provide greater context and comparison for al-Fath.

At the one-day workshop, faculty and graduate students with advanced reading knowledge of Arabic came together to unearth the treasures of this periodical for a new audience. Dr. Ayoub introduced the conceptual framework of the workshop and the thinking behind the selection of passages to read. Dr. Agbaria provided an excellent introduction to the scholarship of the period and the biography of al-Fath’s founding editor, Muhibb al-Din Khatib. I took the attendees through the acquisitions process for this title and introduced contemporary works from our collections, demonstrating the great company that al-Fath keeps in the stacks. These titles include Akhir Sa’ah, al-Qiblah (another journal edited by Khatib), Jaridat al-Balagh al-Usbu’i (a selection of which is now part of UT Libraries’ Digital Collections), and al-Muqtataf. We then spent the morning reading passages together, taking turns leading the discussion. For the afternoon session, we divided into small groups to read reports of legal cases and then share out our analysis with the others.

The workshop’s attendees walked away with a greater understanding of 20th-century Arab scholarship and legal thinking, and intimate familiarity with a (new-to-them) text that they can use in their teaching and research. Even faculty who have been with the university for most of their careers learned from the introductions and book display about materials helpful for their research that they hadn’t known were in our collections. The graduate students had the essential experience of close-reading a text in Arabic, which is a skill that they will need for their thesis and dissertation research . In many ways the workshop followed a classic philological approach by focusing on reading a text. However, through collaboration, and by combining the expertise of scholars 1) in a range of fields within the discipline of Middle Eastern Studies and 2) of different experience levels, we were able to read al-Fath in its own context, building the bigger picture against which to lay our understandings of discrete intellectual and political trends.

Banking on Ephemera

Before the pandemic, I began accepting donations of Middle East banking and finance materials: pamphlets, brochures, reports, and guides. These formats are the kind usually produced only once as an annual bank report, or a visitor’s guide to a financial institution that would’ve been updated regularly (and the outdated copies destroyed). For their impermanent nature, they are known as “ephemera” in the library world. They are inherently rare, as they were produced only once and in limited numbers. On top of that, most people would probably dispose of such materials in their personal possession. Think about the last time that you visited a tourist site and received a map or brochure––did you keep it? If you did, had it been folded or creased, beaten up at the corners from use? To find such materials at all, and then to find them in pristine condition, is rare indeed. I am sincerely grateful to the donor, UT Austin Emeritus Professor of Government Clement Henry, for his generous gift, which has made UT Libraries a destination for research on Middle East banking in the 20th century.

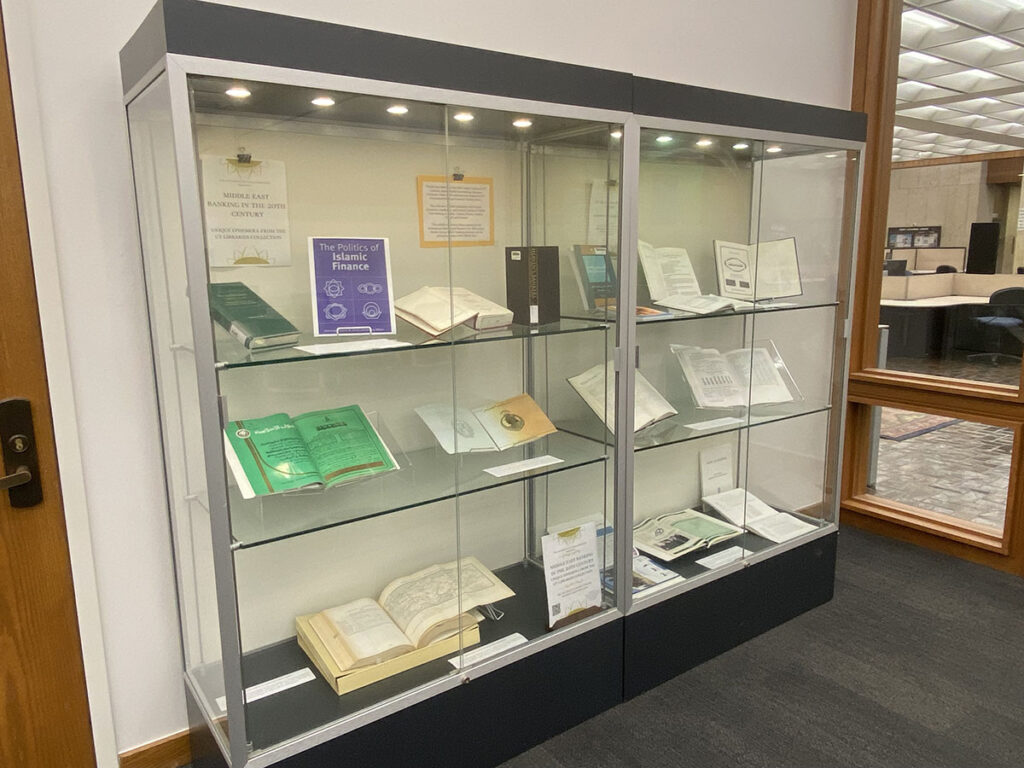

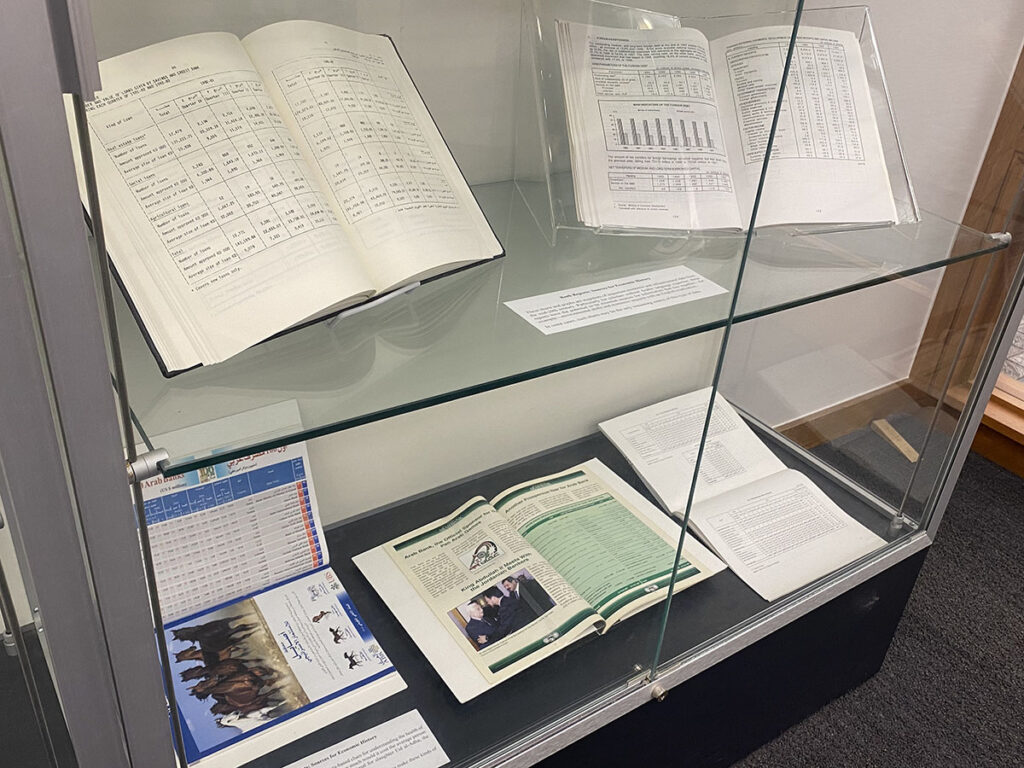

In accepting the gift of these materials, I recognized that they would be something to advertise widely to increase their accessibility. The UT Libraries’ Digital Stewardship department created superb images of some of the donated materials, as well as of some of our existing Middle East bank-related holdings, which I was able to turn into a digital exhibit. I also had the opportunity to build a physical exhibit in the Perry-Castañeda Library Scholars Commons, which was on view from November 2022 – March 2023. The physical exhibit featured some materials from the digital exhibit, and a number of other items that are better appreciated in person. One of those items is a map of the Turkish Central Bank branches and country infrastructure in the Central Bank’s 1955 annual report. A bank report is probably not the first place a researcher would think to find a map of Turkish financial and transportation infrastructure, which is why I wanted to highlight these materials for researchers at all levels of experience. My role as librarian is to make critical connections between researchers and the materials that will make a difference for their scholarship, and my day-to-day observations from our collections are essential for that work. The digital and physical Middle East banking exhibits were ways that I could demonstrate the scholarly utility of ephemeral, often neglected materials such as these.

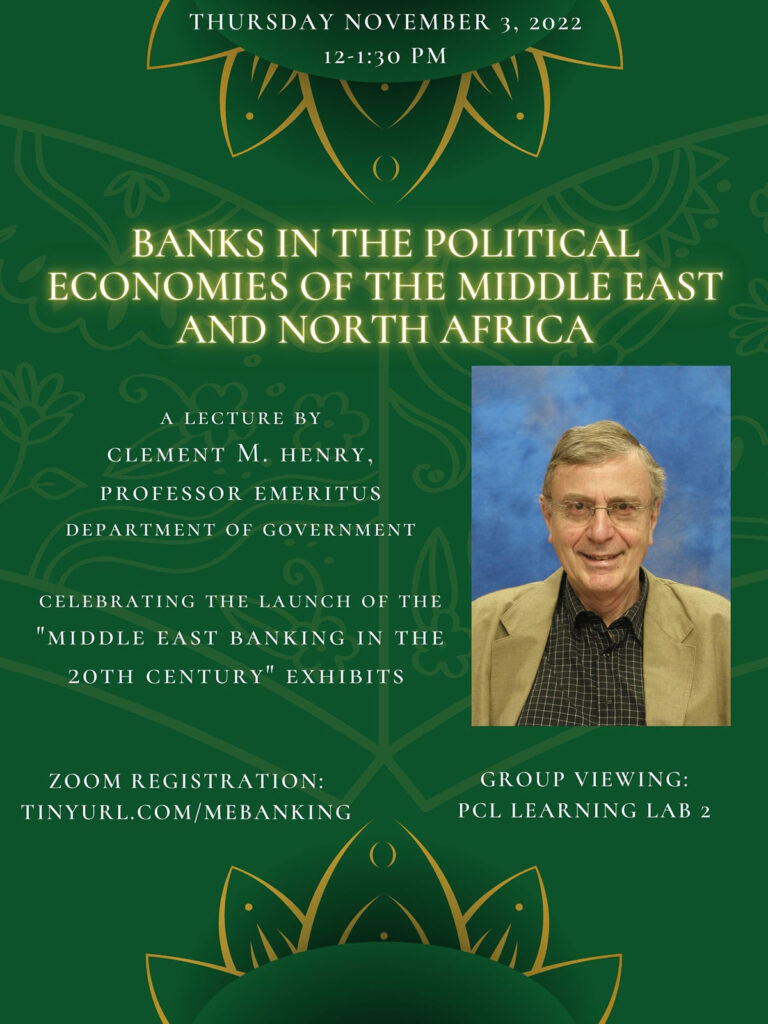

To honor the launch of the exhibits and the efforts of Dr. Henry to donate his incredible personal research collection to UT Libraries, the UT Libraries hosted a lecture by Dr. Henry titled, “Banks in the Political Economies of the Middle East and North Africa.” I sought to build upon the exhibits and Dr. Henry’s lecture by holding two “study hours” in the days preceding the main lecture event. Partnering with faculty in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies, I brought two advanced undergraduate courses into the Perry-Castañeda Library Learning Labs to physically engage with our Middle East banking collection. I pulled a selection of materials that I hoped would be fascinating and created an exercise for the students to do in small groups. A tangential benefit of the Middle East banking collection is that it is in English, French, Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, and comes in a variety of formats from monographs to pamphlets to serial reports. There’s a little something for everyone, and language does not need to be a barrier to understanding. This was the intention of the original authors of the bank reports and pamphlets, of course, who sought to broaden the investor base of their institutions.

As primary sources, these materials represent a period of rapid change and interaction with the conceptualizations and implementations of the term “modernity.” Students in two very different courses on the contemporary Middle East were able to handle these rare and special ephemera and consider such issues as: choice of language(s); paper quality; color versus black and white images; length; frequency of publication; and choice of topics covered in the material (some of which were quite political). At a time when many students engage with library collections in a primarily digital form, and often with secondary sources that may only summarize the primary essence of the research, these study hours became precious moments for students to connect with the different, unfamiliar medium of ephemeral print and determine for themselves what it signifies to have access to these materials.

Keeping Special in the Stacks

So what happens when a valuable, rare item is kept in the regular stacks of the library’s general collections? It gets used and appreciated. Researchers access it more readily, students can stumble upon it while working on a term paper, and the item itself remains in a context of similar and complimentary works. It adds value to its shelf and stacks row and makes exploring the floors of the university library that much more interesting. There is almost no barrier to access, particularly in the public university environment of UT Libraries, and so even the most novice of researchers has a chance to benefit from this material. As Middle Eastern Studies Librarian, I intend to keep adding special and rare materials to our collection, not simply or only as a means of distinguishing the UT collection from others, but also because it is possible and currently a beneficial practice to make these materials available to all researchers who walk in our doors. I believe that the value of these items exists in the perceived tension between their rarity and their easy physical access, and I ask readers of this blog post to reconsider the hierarchy of rare and general collections.

Dale J. Correa, PhD, MS/LIS, Middle Eastern Studies Librarian & History Coordinator, University of Texas Libraries