BY HANNAH ALPERT-ABRAMS

How can we process 80 million pages of historical documents?

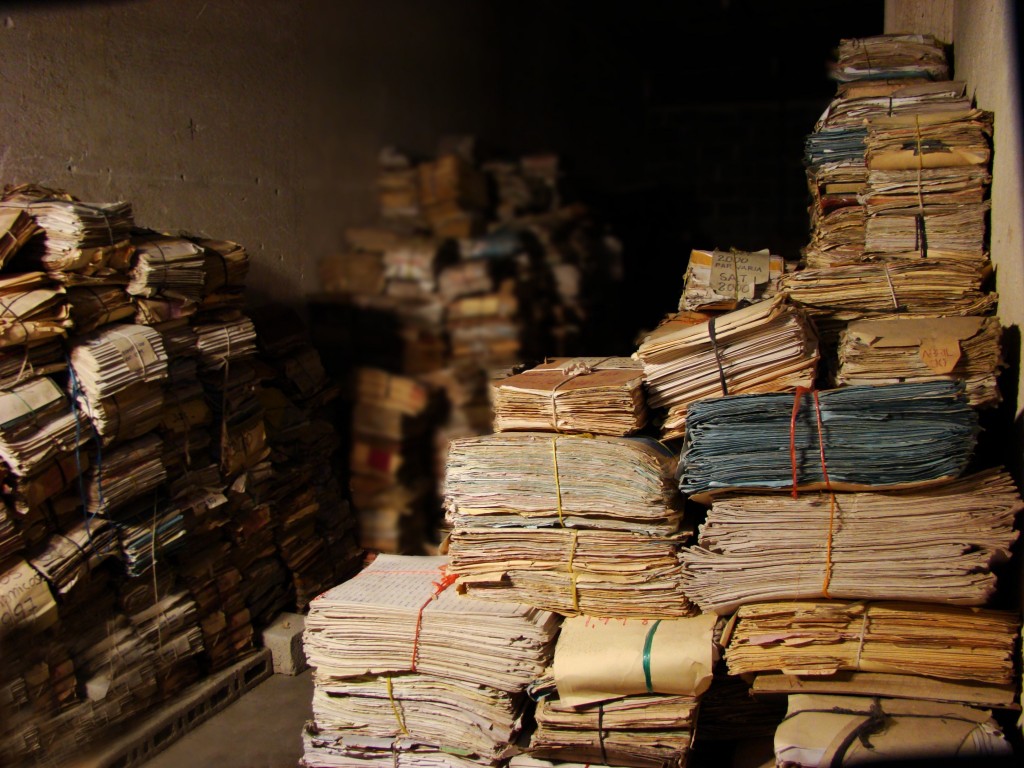

The question is a philosophical one, about the ability of our minds to conceive of such a large number of documents. The Archivo Histórico de la Policía Nacional (Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive, AHPN) in Guatemala City contains about eighty million documents, or about 135 years of records from the National Police of Guatemala.

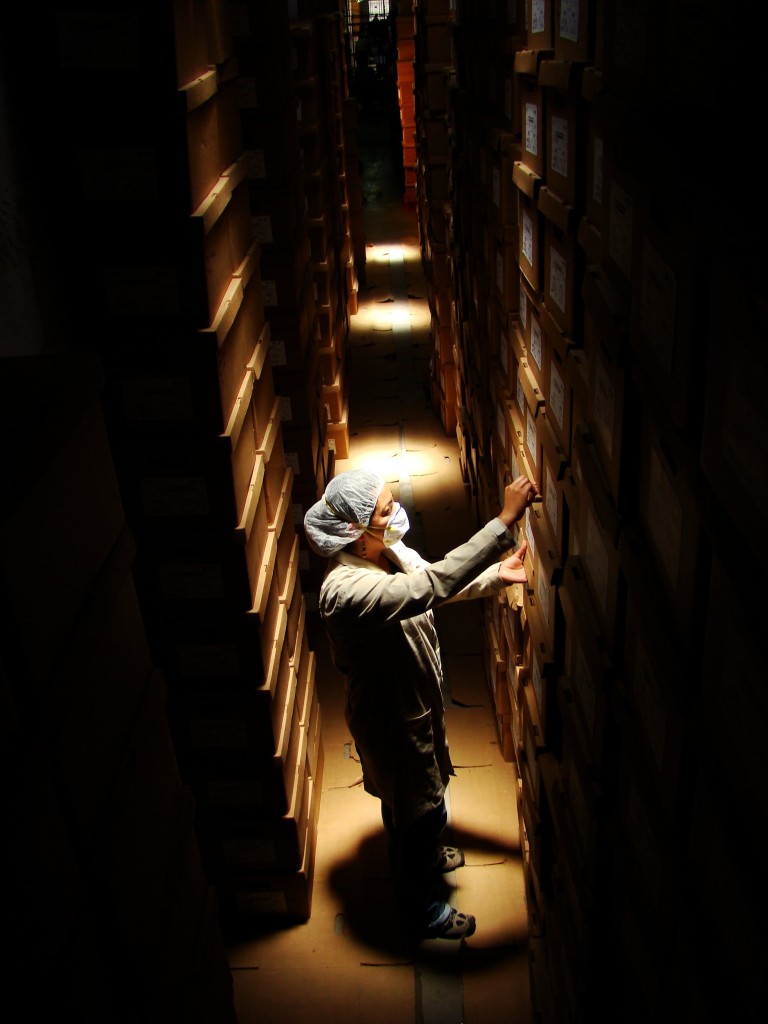

According to one estimate, that means the collection requires about three-quarters of a mile worth of shelf space. In comparison, the Gabriel García Márquez collection at the Harry Ransom Center takes up about 33.18 feet of shelf space. The Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers at the Benson Latin American Collection take up about 125 feet.

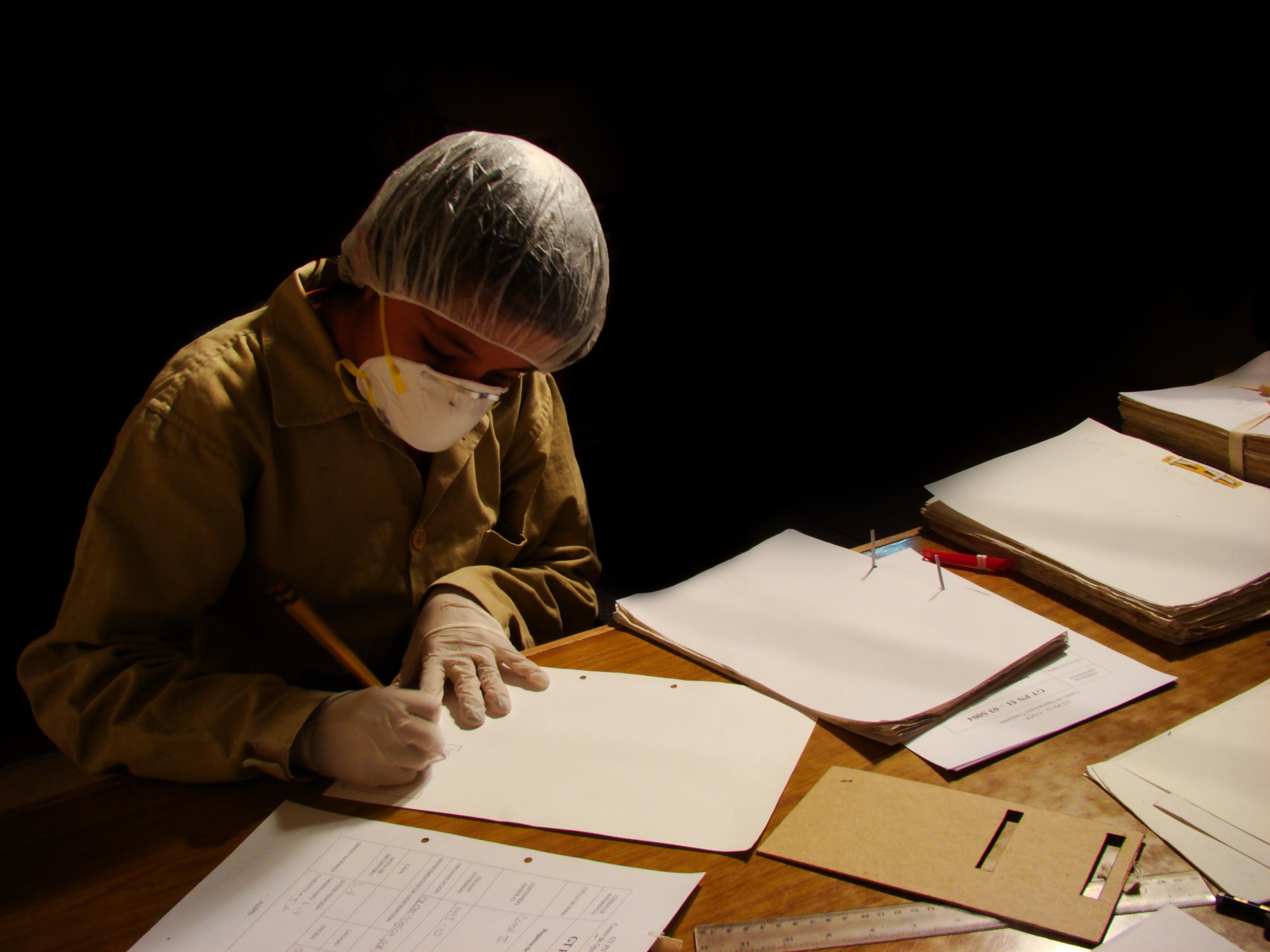

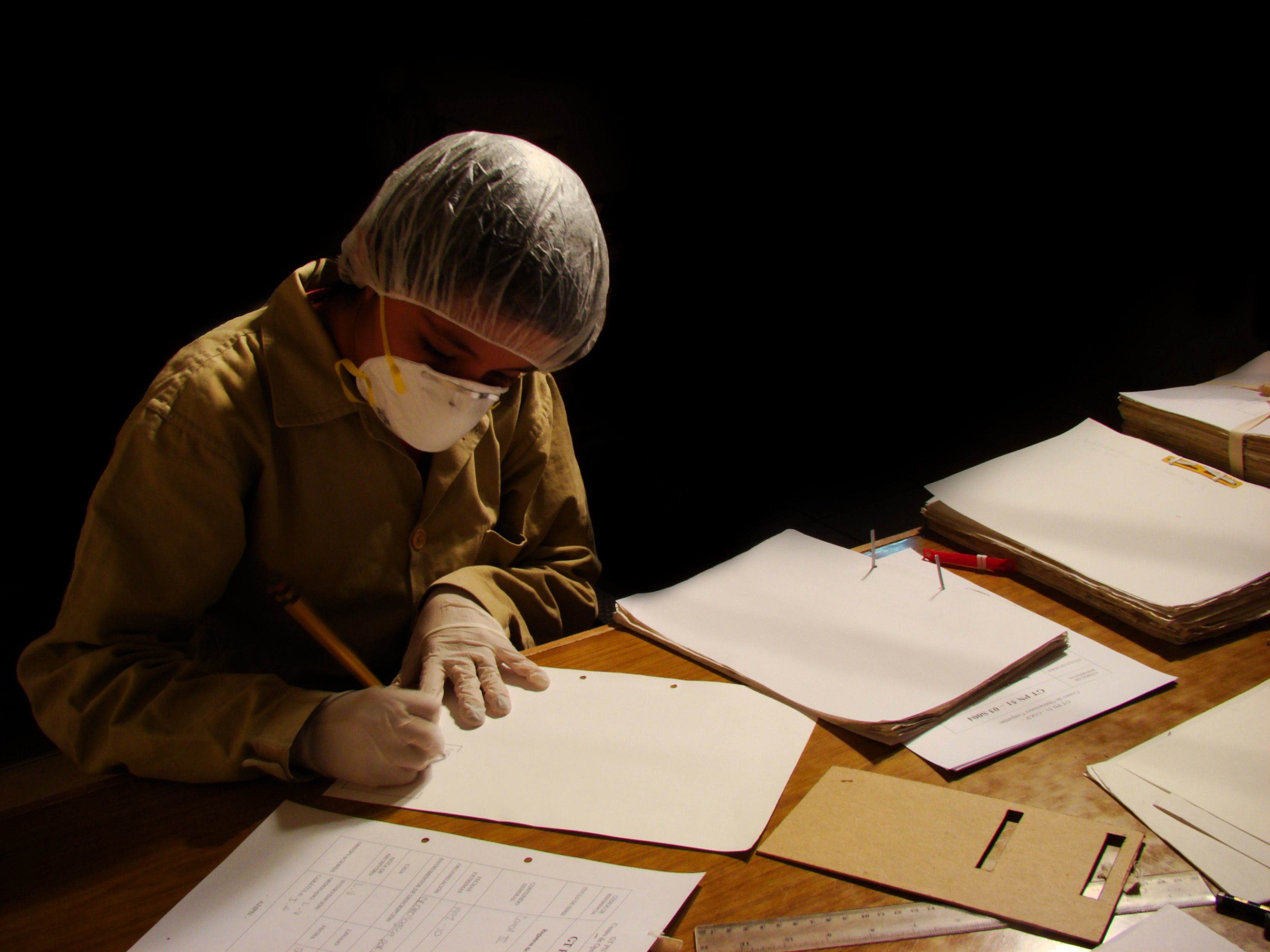

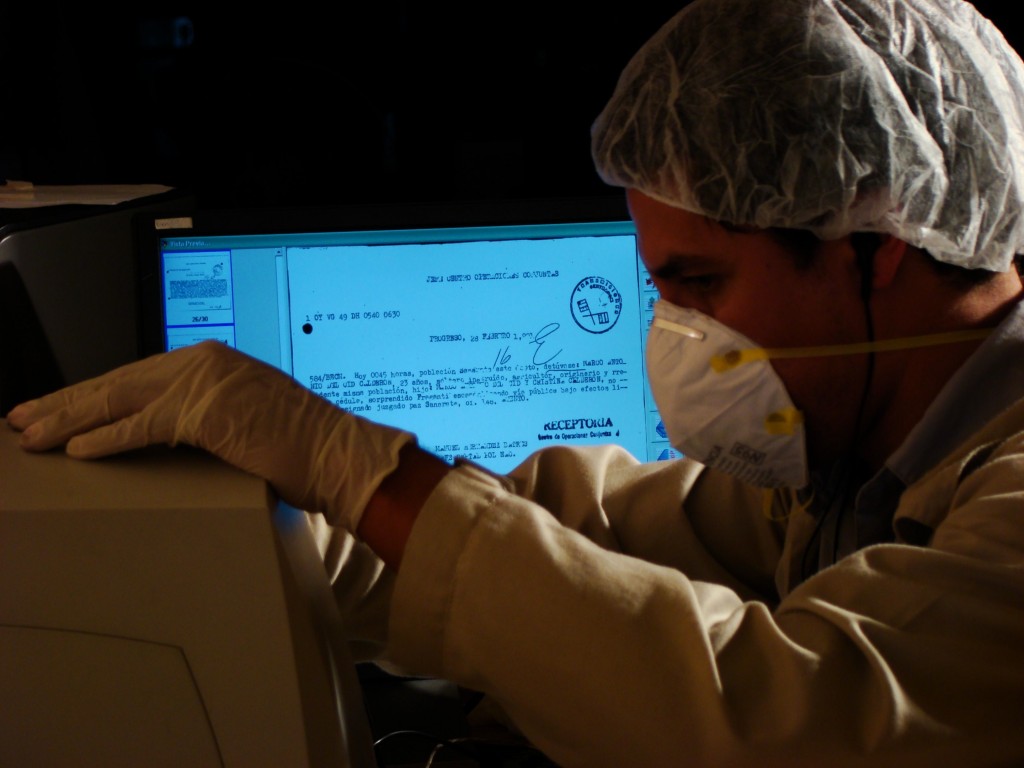

The question is also a technical one, about the difficulty of gathering, organizing, and providing access to an inconceivably large collection. For over a decade, archivists at the AHPN have been racing to clean, organize, and catalogue these historical records. In 2010, the University of Texas at Austin partnered with the AHPN to build an online portal to a digital version of the archive.

As the CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in data curation and Latin American studies at LLILAS Benson, I have been tasked with the challenge of figuring out how best to support this ongoing partnership.

I visited the AHPN last November, just before Guatemala celebrated the twenty-first anniversary of the signing of the peace accords that ended the country’s decades-long armed conflict (1960–1996). Together with Theresa Polk, the post-custodial archivist at LLILAS Benson, I went to Guatemala to learn about the digitization efforts at the AHPN, and to celebrate a major milestone: when we arrived, the archive had just finished digitizing 21 million documents.

Digital Access to Historical Memory

The AHPN hard drives may fit in a carry-on, but hosting and providing access to the 21 million digital documents they contain is not a trivial task. When the University of Texas launched the digital portal to the archive in 2011, it was a bare-bones service with minimal browsing or search capabilities. Since then, the collection has doubled in size and grown exponentially in complexity. Our challenge—and the reason we were in Guatemala City—is to figure out how to represent that complexity online.

According to the web analytics, the majority of visitors to the website are based in Guatemala. These users are largely looking for two kinds of information. Some are members of human rights organizations conducting research related to police violence spanning over three decades of internal conflict in Guatemala. The rest are people trying to find out what happened to their loved ones, victims of violence during that same period. That’s why the anniversary of the peace accords matters to the collection. Organizing these records and making them available to the public has been one of the many ways that Guatemalans are reckoning with their country’s past.

There is an urgency to serving these research communities, and our top priority is to provide easy access to information. Easy searching of the archive, however, remains elusive. The archival documents are organized according to the baroque structure of the police bureaucracy. To find documents requires an intimate knowledge of that organizational structure.

Searching would be easier with richer descriptive metadata. If we could extract names, locations, and dates from the archival materials, it would make it easier for a person to search for their loved one, or a researcher to learn about specific neighborhoods or historical events. But extracting information from 21 million documents is a resource-intensive task, and the technologies for automating those processes remain imperfect.

Search is not our only priority, however. As I learned firsthand, to visit the AHPN is to be immersed in the context of its construction and its size. The dark, narrow corridors, concrete walls, and grated windows are a testament to the building’s history as a police prison. The violence of the archive is always close at hand, despite the hope it represents. One of our challenges is to recreate that experience for users of the digital archive.

Furthermore, as I learned from talking to the head of the Access to Information unit, the process of searching for information at the AHPN has been designed in a way that allows the archivists to bear witness to the memories of the researchers. Each visit begins with a question: Tell us what happened to your loved one.

The question has a practical purpose. It allows the archivists to glean the information that will make it possible to locate the necessary records from among the millions of files. But in answering this question, families are also sharing an intimate story with an archivist, an act of strength and also, often, of courage. Can a digital archive create similar opportunities for those who are unable to make the visit in person?

Imagining Digital Futures

The partnership between the University of Texas and the AHPN is an extraordinary opportunity for our institution to create new paths to historical research, and to support the international preservation of historical records. It allows us to honor and support the vital work of the archivists at the AHPN, while working at the forefront of digital collecting.

This partnership has also encouraged us to rethink our assumptions about digital archives. We often imagine a digital archive as a simple reflection of a material collection. But 21 million digital pages have very different infrastructure and support requirements than their material counterparts. The needs and expectations of online users are different, too.

In many ways, in imagining the future of the AHPN portal, we are imagining the future for digital collections at the University of Texas more broadly. The size and complexity of collections like the AHPN push the limits of our understanding of the role of libraries, and librarianship, in the digital age. They draw us into a future where scholarship, community-building, and access to information are inextricably linked.

_____________________________________________________________

Hannah Alpert-Abrams is a CLIR postdoctoral fellow in data curation at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections at The University of Texas at Austin.