“Zines are not a new idea. They have been around under different names (ChapBooks, Pamphlets, Flyers). People with independent ideas have been getting their word out since there were printing presses.” ― Mark Todd, Whatcha Mean, What’s a Zine?

As institutions traditionally charged with gathering and providing access to the broadest range of information, libraries have in large part transitioned their focus from the physical to the digital realm of resources. But there are pockets of attention that remain fixed on collecting those materials that hold significantly greater value in a corporeal state.

In 2010, Fine Arts Library (FAL) Head Librarian Laura Schwartz joined a fledgling movement of librarians across the country in establishing a collection of DIY pamphlets, popularly known as “zines.”

In 2010, Fine Arts Library (FAL) Head Librarian Laura Schwartz joined a fledgling movement of librarians across the country in establishing a collection of DIY pamphlets, popularly known as “zines.”

Zines — short for “fanzines” — take a variety of forms, but are generally self-published and noncommercial, homemade or online publications often devoted to specialized or unconventional subject matter. Traditionally, zines have been published in small runs — less than 1000 copies — and most are produced on photocopiers or by other, more economical means.

At a time when virtually anyone with access to the web can reach an audience, the idea that your local Kinko’s still has the patronage of a subculture of the most indie of independent publishers seems almost absurd.

And yet, the niche market continues to thrive, and has even seen a degree of proliferation, especially in the area of social justice, an association which would no doubt have pleased Thomas Paine.

Schwartz is determined about her motivation to build the collection. “This is a form of art,” she says. “Museums or galleries do not typically collect this format, so it is incumbent upon libraries to do so.”

“Libraries have a history of collecting ephemeral and personal materials,” says Schwartz. “That is the essence of archives. Libraries are capturing a slice of history and culture of a particular time period by collecting zines.”

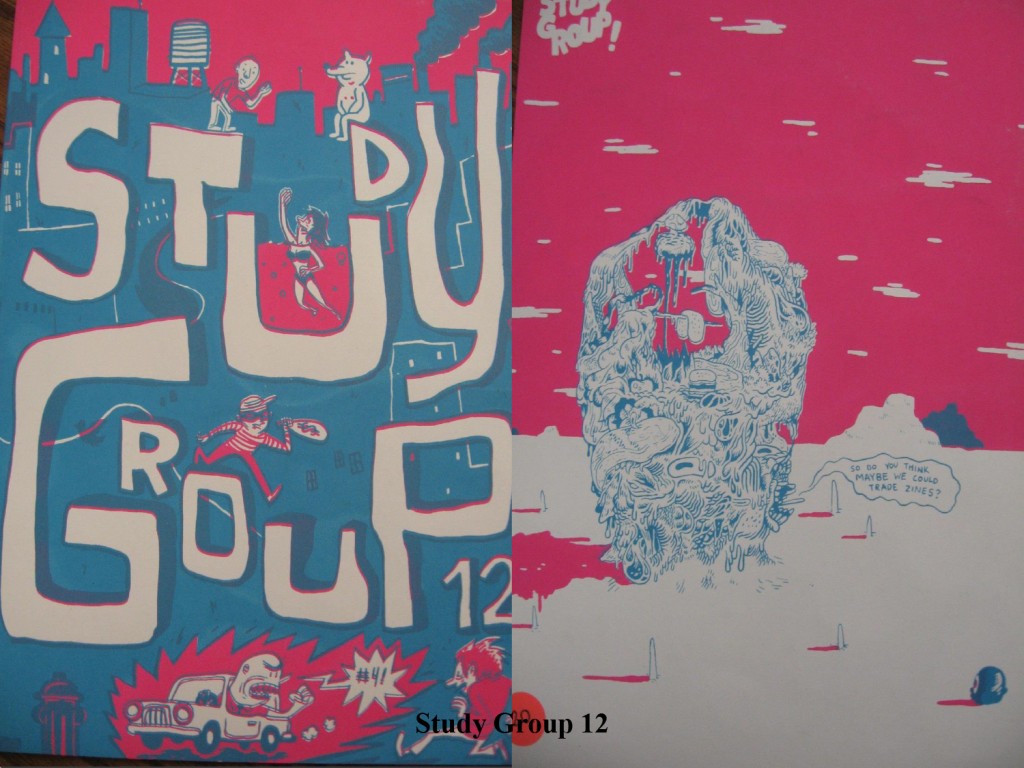

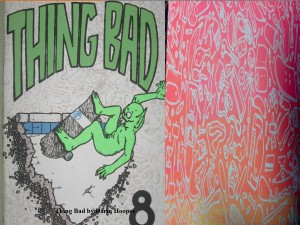

The FAL’s zine collection currently maintains over 200 items of state, regional and national origin, and recent donations will potentially double the size of the resource. The content of the materials covers a range of subjects including art, photography, music, skateboarding and Texas culture.

The FAL’s zine collection currently maintains over 200 items of state, regional and national origin, and recent donations will potentially double the size of the resource. The content of the materials covers a range of subjects including art, photography, music, skateboarding and Texas culture.

Schwartz was fortunate at the time of the collection’s inception to have a ready resource for development in the form of the manager of a specialized local bookstore, Russell Etchen of Domy Books. Being an artist and autodidact in zine history — as well as a curator/manager for the shop/gallery — Etchen had an informed perspective on the significance of the genre, and offered his insights as a service to preserving the form.

“Laura had an innate sense for what would and wouldn’t work when she started building the collection,” says Etchen. “We would walk through the store together a couple times a year, and I would share the works that I felt, at the time, were most deserving of preservation.”

“When it comes to the underground, there are no ‘right zines’,” says Etchen. “There is a very decentralized history behind self-publishing and generally we chose works that I felt had a unique history behind them or ahead of them.”

Schwartz has a meager budget for collection development, but the part of the beauty of this type of special collection is that the form doesn’t necessarily require the resources that, say, a Ransom Center might need. Still, the FAL has benefited from the dedication that seems to be characteristic of zine devotees — they tend to hold on to their collections, and want to see them preserved, as well.

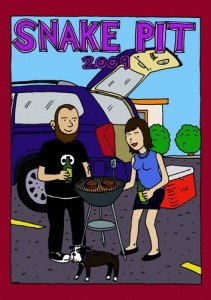

One of the recent benefactors to the FAL collection — David DiDonato — donated his stockpile of zines, many from the DC area, including a rare first edition of the Austin-based Snakepit. Like many zine followers, DiDonato came to the medium through his connections to music.

One of the recent benefactors to the FAL collection — David DiDonato — donated his stockpile of zines, many from the DC area, including a rare first edition of the Austin-based Snakepit. Like many zine followers, DiDonato came to the medium through his connections to music.

“I got into collecting zines just from being involved in the underground music community,” says DiDonato. “I had friends that made them, and even people that I didn’t know that well would give them away at shows/record stores/book stores. This was a time before alternative sources of information were readily available, so zines were a way of spreading news that wasn’t covered in major media outlets.”

Of course, the question of relevance for zines in an age of blogs, social media and a multiplicity of communications options remains, but Schwartz doesn’t see conflict. “The internet has been great for zine production,” she says. “The DIY movement has had a resurgence as a backlash to the digital age, and folks are interested in the tangible, in making, now more than ever.”

“There are similarities, of course. Zines and blogs both give people a voice.”

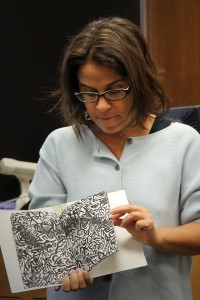

Beyond just preserving a resource for individual research or personal inquiry, Schwartz has created connections with Department of Art & Art History faculty to highlight and utilize the zine collection, giving it scholarly cache, as well. Associate Professor Leslie Mutchler leads a Foundations study in which zine-making projects are a component, and lecturer Jason Urban teaches a studio course on printmaking in which he hosts classes in FAL to provide his students personal interaction with the zines. Both Mutchler and Urban use the materials to show examples of what has been done in the past, and each semester 2-3 zines produced in Mutchler’s course are added to the collection.

Beyond just preserving a resource for individual research or personal inquiry, Schwartz has created connections with Department of Art & Art History faculty to highlight and utilize the zine collection, giving it scholarly cache, as well. Associate Professor Leslie Mutchler leads a Foundations study in which zine-making projects are a component, and lecturer Jason Urban teaches a studio course on printmaking in which he hosts classes in FAL to provide his students personal interaction with the zines. Both Mutchler and Urban use the materials to show examples of what has been done in the past, and each semester 2-3 zines produced in Mutchler’s course are added to the collection.

Assistant professor Susan Thomas of Long Island University’s Brooklyn Library has written extensively on the artistic value of zines, and last year took part in a panel discussion with faculty and artists on the scholarly value of zines at the FAL. She sees in zines an opportunity for teachers to contextualize modern technology, and as another creative medium for inquiry.

“Zines are unique primary sources that provide scholars opportunity to criticize and interpret,” says Thomas. “Their study recognizes the value of networks, subcultures, and fandom; they also often produce alternative perspectives about a city or neighborhood.”

“Zines are unique primary sources that provide scholars opportunity to criticize and interpret,” says Thomas. “Their study recognizes the value of networks, subcultures, and fandom; they also often produce alternative perspectives about a city or neighborhood.”

Still much of the allure of zines is about a personal connection the individual finds in the work. Another donor to the FAL collection — Katherine Strickland, who also happens to manage the PCL Map Collection — related her introduction to zines, and it encapsulates much about the intrinsic meaning of these ephemeral works of art:

“I remember my introductions to zines. It was 1986 and I was a show at the Bone Club, a punk club in San Antonio, Texas. We hung out on the sidewalk between bands, because it was always so hot inside and there wasn’t enough room for bands to set up and the crowd. I was talking to my friend Holly and someone handed me the most amazing photocopied zine, called TV Viewers Guide and my mind was blown. My parents subscribed to Rolling Stone and I had always bought mainstream magazines like Hit Parade, but this was different. They were reviewing bands that even Spin wouldn’t touch and interviewing my friend’s bands. And it was beautifully messy. Cut out words from newspapers, handwritten, and typed! It was everything that appealed to me about punk music, it seemed to say, ‘You can do this, too, and you should. Come on!’”

If you’re interested in contributing to the FAL’s Zine Collection, contact Laura Schwartz at via email or (512)495-4476.