There’s no doubt that the embrace of digitization by museums and libraries has significant benefit for the devotees of art history. The preservation of the cultural record from the degrading effects of time is the most utilitarian benefit of the practice, but archival digitization also allows for non-linear consideration of creative works in its ability to allow art to be partnered with other data, information, critical context, etc. Digitization is, though, limited by the sheer volume of historical works that exist and by that which continues to be created. Sometimes, the only sure way for art to be preserved digitally, is for a specific need to arise.

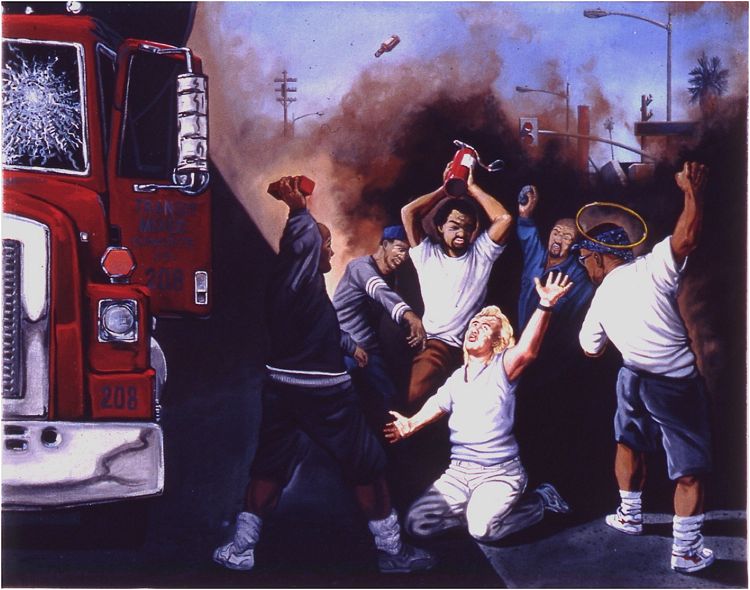

Such is the case with the work of Sandow Birk, a visual artist in southern California, whose art contemplates modern American society with a nod to past masters.

Earlier this year, UT College of Fine Arts Ph.D. candidate Rose G. Salseda began research for her dissertation by interviewing several artists who created artworks in response to five days of civil unrest caused by a jury’s acquittal of four white Los Angeles police officers who had been charged with the videotaped beating of Rodney King, a black motorist.

“These riots were the first in history to be heavily documented through live news coverage, film, video, and photographs,” says Salseda. “Yet, past scholarship has failed to recognize the potential encompassed within art to speak to the history of the riots.”

“My dissertation seeks to unearth a missing visual narrative. Moreover, it reveals the capacity of art to unhinge and complicate polarizing histories of the 1992 LA Riots.”

Along with Birk, Salseda had interviewed sculptor Seth Kaufman and graffiti artist Man One, only to discover that virtually none of the artists’ work from the 1980s-90s had been digitally preserved.

“It really alarmed me,” says Salseda, “because, since most of these artworks were in private collections or in unprotected public spaces, no one would have the opportunity to see them again.”

In working with the Birk, Kaufman and Man One, Salseda was able to gain access to slides, photos and ephemera directly from the artists themselves.

“Birk was the first of the three artists that I met. He shared slides of his work with me and I was surprised that only a few had ever been digitized,” recalls Salseda. “I knew that if the documentation of the work was not updated, it may continue to be overlooked by scholars, teachers, and others.”

Salseda remembered from previous work with staff at the Visual Resources Collection (VRC) at UT that a library might be able to help her capture the imagery, thus ensuring that it would be preserved for both her use, as well as the use of future researchers. But she needed to find someone close by in Southern California that would be willing and able to assist.

“I contacted the head art librarian at Cal State Long Beach — the university closest to Birk’s studio. She then directed me to Jeffrey Ryan, the CSULB Visual Resource Center staff,” recounts Salseda. “I spoke with Ryan and he volunteered to digitize Birk’s images, as well as that of other artists whose work has not been digitized. Thus far, he has digitized several hundred slides for me and the artists I work with — all of which are now available to CSULB students, faculty and staff.”

Salseda then followed up with Sydney Kilgore, media coordinator for the UT’s VRC — an actively growing collection of some 80,000 digital images of art and architecture located at the university’s Fine Arts Library — to see if it would be possible to ingest a selection of Birk’s work into the university’s digital media repository, the DASE (Digital Archive SErvices) Collection, for the benefit of students, faculty and researchers at UT.

“When Ms. Salseda approached us with the Birk project we knew it would be another win/win situation,” says Kilgore. “In this case, the VRC additions resulted with Rose Salseda wanting to share her research, and artist Sandow Birk being willing to personally choose and share 30 images of his art which he felt were representative of his career.”

Salseda is currently working with Kaufman and Man One to secure digital images of their work for inclusion in the VRC, as well, which are expected to arrive next year.

She believes that there is a larger history to be told by the art that was created in the wake of the unrest, but because of a lack of documentation, the story of the period has an incomplete context.

“Due to the numerous artworks the riots inspired and the surprisingly scant scholarly and curatorial consideration of this work, I am positive there are many more artworks out there that have not been properly digitized and archived,” Salseda says. “In general, the lack of art history on the riots and the unbalanced focus on a small pool of artists means that other artist contributions to this important episode in LA and US history are forgotten or go untold.”

It’s this personal, practical experience that Salseda had in the process of her own research that prompted some realizations about the temporality of art and the necessity of digital preservation.

“I have come to realize even more the importance of digitizing images. These images are essential when original artworks are lost, reside in private collections, and/or are irregularly exhibited,” she says.

“It is also important for artists to update the format of their image archives to ensure that future generations have the potential to access images of their art when viewing equipment for older formats become scarce or defunct,” says Salseda. “However, taking on such tasks are out-of-reach for many artists: the equipment is expensive, as is hiring private companies to do such work, and it can take an extraordinary amount of time if one does not have the proper equipment or assistance.”

“Resources like UT’s VRC and CSULB’s Visual Resource Center are invaluable. From personal inquiries to professional ones, like documenting my exhibitions or archiving images related to my dissertation, I knew I could rely on these resources. I hope more students and faculty realize the important indispensable services they offer.”

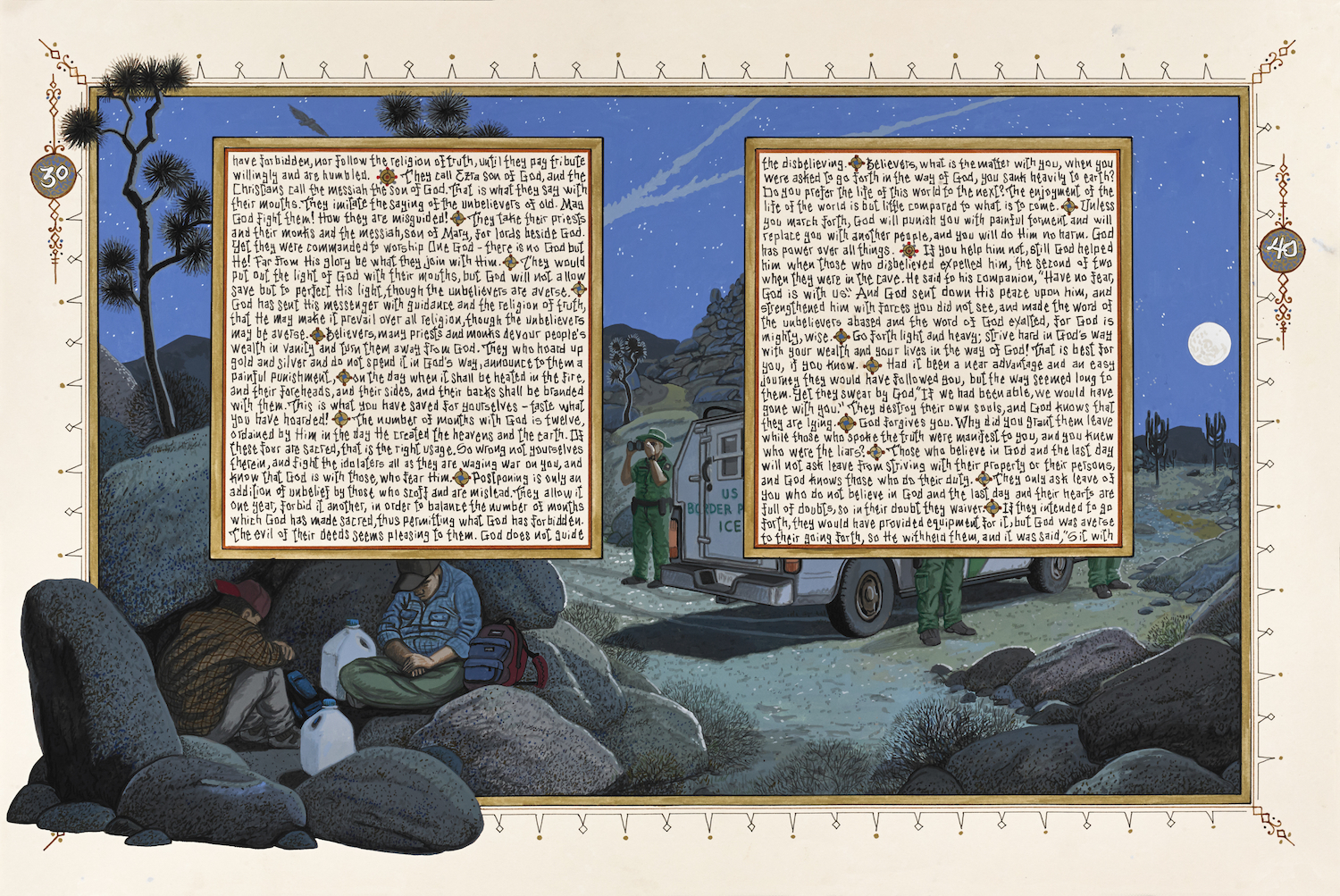

An exhibition featuring Sandow Birk’s “American Qur’an” is currently on view at the Orange County Museum of Art.

Sydney Kilgore, Rose Salseda and Thao Votang contributed to this article.