Texas may pride itself in being big, but as anyone around the Forty Acres these days knows, that “bigness” is finite.

Back in the early 1990s, as Austin was hitting its stride in terms of growth with the arrival of tech industry and the nascent popularity of the city as a destination, forward-thinking minds at the University of Texas Libraries recognized that the ever-expanding physical collections — which at the time had reached in excess of 6 million books — couldn’t forever be contained on a rapidly growing campus.

To avoid what they saw as a future crisis for the preservation and accessibility of the collections, the Libraries sought and received approval and funding to construct a library facility based on the Harvard Depository — a preservation facility that had been developed at Harvard University in 1986. The goal was to relocate low circulation items into a highly controlled environment with optimal preservation conditions, coupled with a retrieval process to get items back into the hands of users should they be needed.

Sensibly referred to as the “Harvard Model” — which has become a standard for materials preservation — the building layout for the Library Storage Facility (or LSF as it’s known within the Libraries lexicon) is an interconnected structure of generational units situated on the lonely south side of the university’s satellite Pickle Research Campus on a close-cropped berm of desiccated weeds in far north Austin with downtown only barely visible in the distance. The vertically-oriented concrete panel edifice is stark and brutalist, an almost unwitting tribute to its campus counterpart, the Perry-Castañeda Library, a likewise imposing monolith and arrival hub for most of the materials that are retrieved from storage.

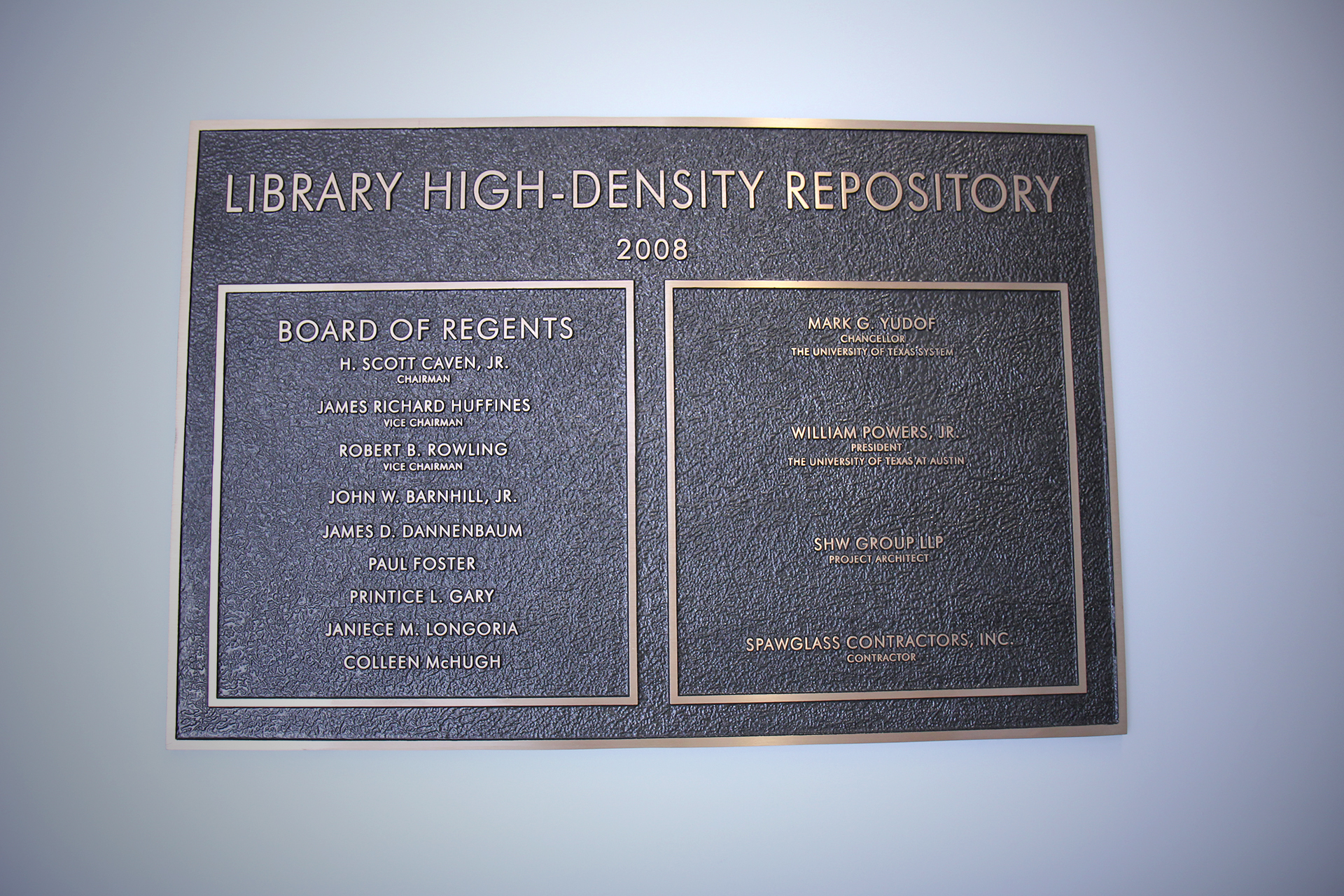

The storage structure itself is actually a series of separate construction projects that spanned several years. The first unit was opened in 1993, the second in 2009 and the third, LSF 3, opened late in 2017 and is currently being filled with library materials.

Each section of the building accommodates 30-ft tall shelving units in a series of aisles and each shelf section (called a “ladder”) is a designated height to fit volumes of like format and size — an almost profane violation of standard library organizational protocols — thereby ensuring the most efficient application of available space. Shelves are accessed via a “picker,” a specially-designed forklift that can be controlled from a spanning basket that can reach the very highest level of the structure.

Everything in the facility is systematically barcoded — the item, the storage tray in which it sits, the shelf on which the tray sits — and that information is stored and managed in an inventory control systems that allows staff to quickly and easily locate any of the 2 million items stored at LSF.

The Library Storage Facility is managed by the Libraries, but additionally serves as preservation storage for collections from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the Harry Ransom Center and the Tarlton Law Library. LSF 2 was even built in part with support from our siblings and rivals down the road at College Station, and as a result, the A&M Libraries have a dedicated aisle of space for materials mingling with the resources of the Longhorn Nation.

Another similar project at A&M’s Riverside campus — the Joint Library Facility — was constructed as a collaboration between the Texas A&M System and the University of Texas System allowing for the storage of widely-held, but infrequently used, items materials across Texas academic institutions. The nature of this facility offers participating libraries the opportunity to pare down some of their materials to a single copy that is then collaboratively stored and served from this shared facility.

Collectively these storage facilities have facilitated substantial growth in Libraries holdings — which now stands at more than 10 million items — by allowing for the transferral of low-use items from overstretched campus locations to the high-density facility at the Pickle Research Campus. We still spend over $1.5 million per year on traditional physical resources – even as the Libraries moves to incorporate the ever growing array of electronic information resources – and we expect this practice to continue for the foreseeable future.

Professional stewardship of library materials is a key part of UTL’s institutional mission. The conditions at LSF are closely controlled to create the best environment for the long-term preservation of materials, with efforts to maintain a temperature of 55°F and relative humidity at 35%. These conditions significantly slow the deterioration of paper, inhibit the growth of mold, and reduce the likelihood of insect infestations. “With the conditions maintained at the facility, you could basically put an item into storage and come back 240 years later to find it in a stable state,” says Ben Rodriguez, who manages the library storage facility. Rodriguez oversees a team of library specialists who help to develop processes and run the day-to-day operations of LSF with the assistance of ten student workers.

“The stability of conditions at LSF reduces the mechanical wear-and-tear that would otherwise occur as paper and leather expand and contract with the changes to humidity levels in a library environment,” says Wendy Martin, assistant director of stewardship. Martin oversees the preservation efforts — both physical and digital — for the Libraries. “Library materials stored in ideal conditions will have a much longer lifespan than materials stored in open stacks space designed for human comfort.”

Beyond the space-saving functionality of library storage facilities like these, there is a compelling financial reason for moving low-use items off-site. A 2010 study showed the cost of storing a single volume in an open library stacks facility is $4.26 per year, taking into account personnel, lighting, maintenance and heating and cooling costs. The cost is pegged at 86 cents per volume for storage at a facility such as the Riverside unit jointly operated by the Texas A&M and University of Texas Systems — representing a savings of $3.40 per volume.

Off-site storage has also allowed the Libraries to respond to changing the changing needs of faculty and students by redesigning some of our library spaces to accommodate collaborative study and new technology resources that help to better prepare library users for transition to a 21st Century economy. As the library evolves from a storehouse for information into a platform for innovation and creating new knowledge, having the option to reimagine spaces to meet the changing expectations of the public enhances the library’s relevancy.

Of course, none of this storage would mean very much, though, if the Libraries weren’t also constantly working to improve both the efficiency of access to materials that are selected for housing at LSF, and the selection process itself. Recently, with support from Provost Maurie McInnis, an additional full-time driver and transport vehicle were added for the sole purpose of improving turnaround times for material requested from LSF. Beginning in the fall this driver will make a second daily transportation run between LSF and the main campus. This means patrons can expect to receive email notification of an item being ready for pickup within one business day of their initial request. With the Provost’s support we were also able to hire an additional staff member at LSF, providing the necessary staffing capacity to pull materials for delivery twice daily.

Libraries’ subject liaisons work on a daily basis with university faculty and researchers to build collections that support the University’s teaching, learning, and research mission, in both core and emerging disciplines. The undulations of academic and research focus at UT are the subject of constant analysis by library professionals that, combined with specific requests from our users and a robust set of circulation data, help the Libraries make decisions regarding the placement of collections on campus. This is all to say that when decisions are made to take materials from the shelves, it’s not done lightly or without careful consideration. In light of recent concerns about how decisions are made regarding the transfer of materials to storage, the Libraries has redoubled its effort by tasking a cross-functional team with reviewing and improving the decision-making process for relocating resources.

The ultimate goal of having library storage facilities is to continue to grow our collections resources while adapting the way libraries function to meet the needs of modern users. First and foremost, we want students and our other users to be productive. But productivity can be measured in different ways. It comes not only from the opportunity of discovering a book on the shelf run that wasn’t the object of your search, but it can also result in the form of the serendipitous discovery that happens when diverse groups of students get together and share ideas. We want to create conditions that will allow different types of learning and discovery to occur.

Plans are already underway for the next module at LSF, which will not only feature more high- density storage, but will also provide some new kinds of spaces for improved preservation and better access to materials stored at the facility. The new construction — to be called the Collections Preservation and Research Complex —will provide storage for three-dimensional objects and ephemera, additional cold storage (40°F) for film, a proper reading room for onsite research, new processing space and a quarantine room.

The Libraries has been building the magnificent collections we have today for over 130 years, and, with a little effort and care, we can continue to not only grow them, but to make sure that they’re here for many, many more years to come.