Throughout fall semester 2023, a cohort of UT Austin graduate students worked overtime to examine the ethics of digitization and create frameworks for approaching their research in a digitizable environment. They took on the “The Theory & Practice of Digitization Community Symposium” program (co-sponsored by the UT Libraries and the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship for Diversity, Inclusion & Cultural Heritage at the Rare Book School) in addition to their regular coursework and thesis/dissertation research and writing commitments. This program aimed to expand the graduate students’ researcher skill-sets and build reflective approaches to their future professions. The cohort’s efforts culminated in a community symposium that was held on November 9, 2023, in the PCL Scholars Lab, where students, faculty, staff, researchers, and Austin community members came together to learn more about the digitization of cultural heritage.

Each of the students presented on their research, experience in the program, and reflections on digitization of cultural heritage. We have collected their insights to share with you here in the hope that their observations will enlighten the work of others, too.

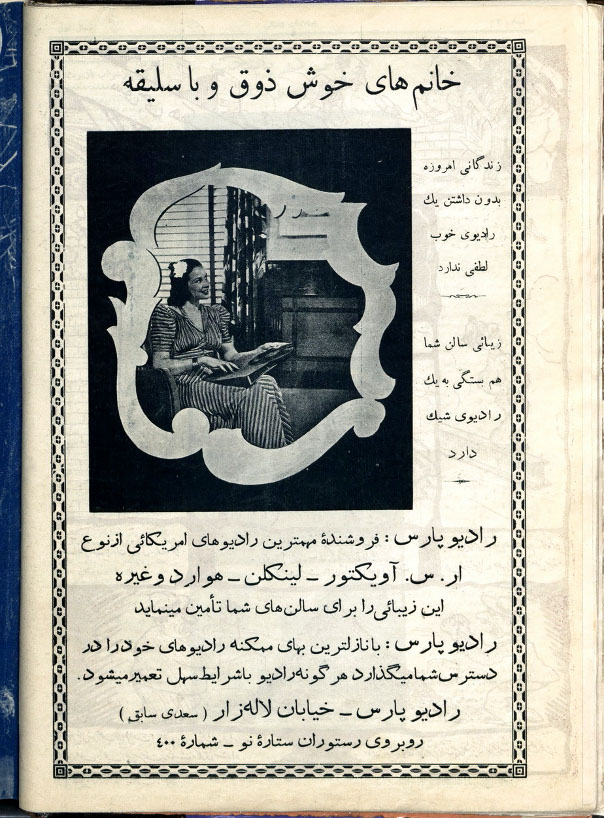

Saghar Bozorgi (PhD student, Department of Middle Eastern Studies)

I started the Theory & Practice of Digitization program thinking about ethical considerations when in/using archives, but mainly looking to get myself familiar with digital methods and whether they can help my project. By the end of the workshop, I learnt how emphasizing a researchers’ project over the archives can reproduce power relationships and hierarchies between different communities and people, especially between the researchers usually located in the “Global North” and the archives that are assumed to be “waiting” for digitization in the “Global South.” As a result, I am now thinking about going beyond my own project and broadening my horizons and considerations when approaching an archive.

In my letter of interest to attend the workshop I wrote about my near-frustration with “the laborious nature” of data collection and its initial analysis, which for my project translates to an infinite period of data collection, leaving little time for writing. This problem “brought me to the idea of digitization and processing texts using digital methods to speed up the process and broaden opportunities for what can be done.” Using digital methods proved to be way more complicated for a Windows user working with primary sources in Farsi. I learnt that OCR programs work with images rather than pdf, so I changed my approach to using Google Docs, which I had tried before in unsuccessful attempts.

While digitizing parts of Ittila’at Mahiyaneh, I was able to recognize some aspects of archival processes and a tiny bit of “what gets to be archived” or “heard” in my own thought process and decision-making. When selecting samples to show during my presentation, I was conscious about the reason why each piece is important. I was hoping to give voice and power to the material that is less visible or invisible in today’s academic and public discourses. One of the pages that I wanted to show was a page in a 1948 issue dedicated to “Palestine” which was continued in several issues. Nevertheless, I persuaded myself to go with other material in order to protect myself and those around me from possible “trouble” and funding cuts, especially because of a recent scary border-crossing experience and the fact that I was not sure about the costs and benefits in a room with a relatively small (and probably sympathetic to Palestinian cause) audience. I remember a point raised in the very first session of the workshop regarding how the archival process has to be considerate of the communities it is serving today so as to not hurt them by using hurtful descriptions. Thus, I have learnt that digitization is not just about scanning material and making them available, but it is also about how archival material, now empowered with a digitized medium, can be talked about. The contrast between my own self-censorship to show the name of Palestine and the keynote speaker’s powerful discussion of the silencing of archives in Israel makes me wonder not only about “what gets digitized and how it gets digitized,” but also who can digitize.

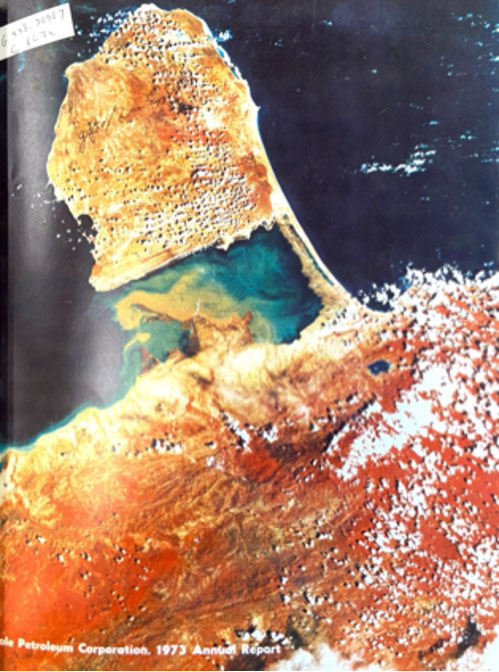

Marcus Golding (PhD student, Department of History)

The Community Symposium on the Theory and Practice of Digitization has provided a valuable hands-on experience for graduate students in digitizing historical records while fostering critical reflection on these processes. Throughout the four sessions, we learned about the best practices in handling cultural heritage materials and digital tools to explore the materiality of these objects. Our interactions with archivists, librarians, and scholars also delved into the politics behind digitization, power imbalances, access to sources, and the significance of community involvement in such initiatives.

For me, the Symposium offered a chance to delve deeper into the issue of privacy within archival collections. Specifically, the complexities arising from balancing open access to materials from historically marginalized groups with the issues of consent regarding the publication of historical documents originating from these communities. Often, the resolution to this issue is complex. The potential to restore the voices of minority groups can sometimes clash with a community’s desire to shield certain aspects of its history from external viewers. Additionally, the Symposium broadened my understanding of digitization best practices and digital tools. I found the insights into setting up camera stands particularly relevant due to the ongoing digitization projects undertaken by my non-profit organization, the Venezuela History Network, in Venezuela.

During the Symposium, I worked with two annual reports (1973) from a Venezuelan oil company, Mito Juan Company, and an American firm, The Creole Petroleum Corporation, both of which operated in Venezuela during the twentieth century. I applied OCR to these texts to facilitate textual analysis, identifying silences and points of convergence between these enterprises in the context of the impending state-takeover of the national industry scheduled for 1976. Through this hands-on experience with digitization equipment, digital tool literacy, and critical reflection on historical documents, the Symposium underscored principles that I firmly uphold. These principles revolve around democratizing access to historical knowledge and community engagement in digitization projects. The end result is to help build collections that safeguard the cultural identity and historical memory of various groups or institutions for posterity.

These are the same guiding principles driving our initiatives with the Venezuela History Network. Our organization is currently involved in at least six ongoing or upcoming projects in collaboration with public institutions, private individuals, and NGOs. The Community Symposium on the Theory and Practice of Digitization has highlighted the importance, as well as the nuances, of making historical knowledge openly accessible. This experience will continue to shape my dedication to the preservation of cultural heritage in the years ahead.

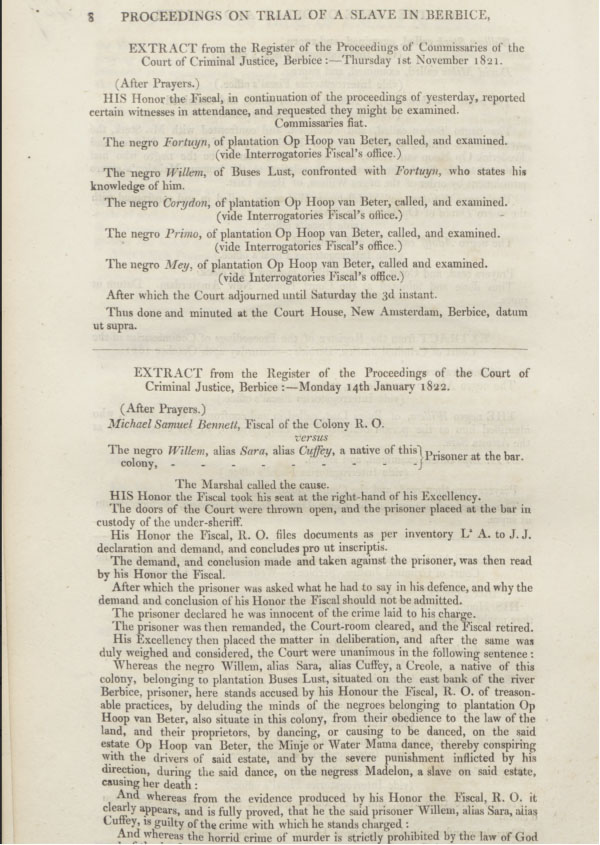

Junika Hawker-Thompson (PhD student, Department of African and African Diaspora Studies)

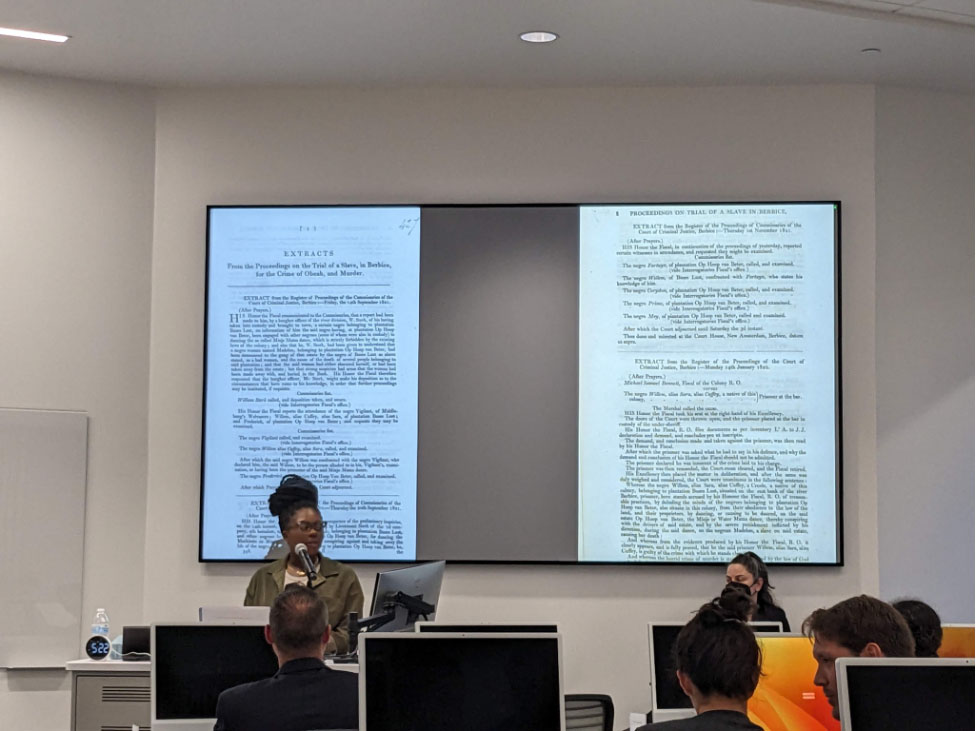

This archival manuscript is from an 1822 court trial titled “Trail of a Slave in Berbice for the Crime of Obeah and Murder” from the Black Diaspora Archive here at the University of Texas at Austin. Broadly, my dissertation project explores how colonial violence shapes race and gender relations within the Demerara region—which is another river region not too far from the Berbice region where this incident takes place. So, when I came across this document, I was interested in thinking through how this colonial document––which is well preserved, clear in its text (meaning, it was instantly machine readable post-digitization), and was bound tightly before my digitization process––plays a role in how law, criminality, and blackness interact within colonial British Guyana.

This case is invested in convicting an indigenous, or Black man, Williem, of murder and “obeah.” The court documents oscillate between calling Willem, “negro” or “native.” For further context, obeah is understood as an African root working, herbal, and spell-casting practice that can impact physical illnesses and metaphysical situations that may require assistance. This practice can be traced back to maroon societies and enslaved people enacting care of each other, themselves, and their larger communities. Obeah can be understood as a practice of agency, liberation, resistance, or care. When considering this brief history, what does it mean for “obeah” to be in a relationship with murder—the worst offense based on Christian morals and law?

I focus on this document because I am interested in how the colonial gaze of this case constructed law and criminality in colonial British Guyana and post-colonial Guyana. I am also interested in what isn’t documented–the dance that allegedly led to the murder of another enslaved woman, the embodied routine of this obeah practice, and obeah being synonymous with murder. While I am not attempting to suggest that murder is correct or should be overlooked, I am more interested in this process of equating a spiritual practice established in maroon societies to murder. I am interested in a practice of witnessing—beyond the colonial gaze—that might highlight the depth of this practice and the presence of ritual.

The future implication of this project is a continued witnessing to honor the complexities of spiritual practice and criminality under colonial regimes. I also wonder about the limits of digitization. Is it possible to make clear this witnessing of ritual and practice in this technological space? I plan to continue to work with this document with the hope and goal that this manuscript will assist in understanding the intimacies of race and gender formation in Guyana.

Raymond Hyser (PhD student, Department of History)

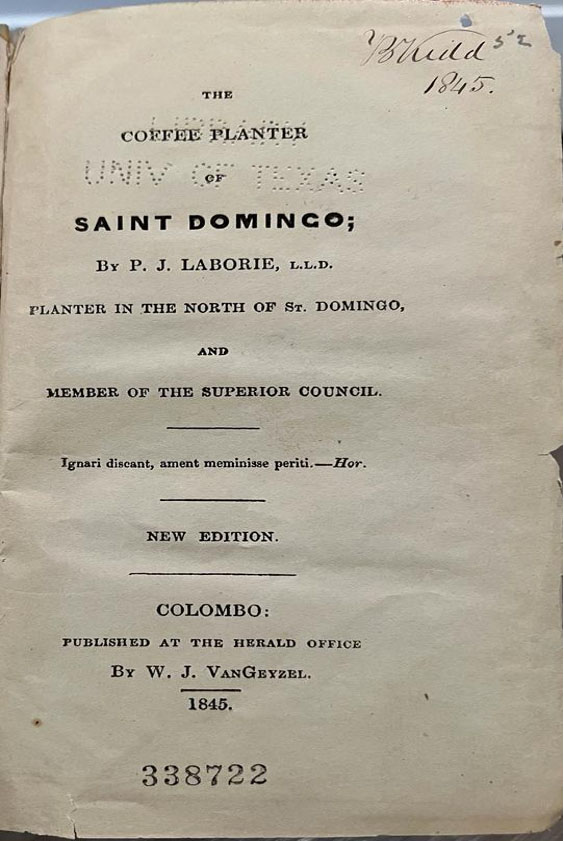

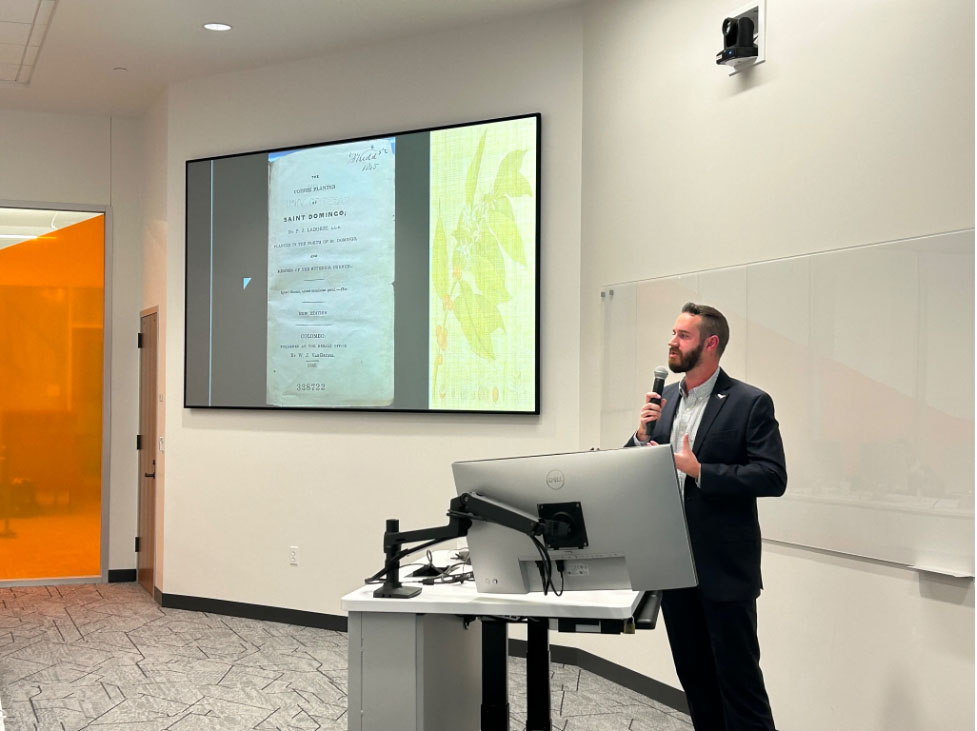

Pierre Joseph Laborie, a French coffee planter in colonial Haiti, fled the island during the throes of the Haitian Revolution and took up residence in nearby British Jamaica. As a thank you, Laborie used his expertise and experience as a coffee planter to write a book to benefit Jamaica’s British coffee planters. Published in 1798, Laborie’s The Coffee Planter of Saint Domingo provides an intimate look at the cultivation and manufacture of coffee in colonial Haiti prior to 1789. Although Laborie’s target audience was the British coffee planters of Jamaica, his work quickly went global. It found its way to Brazil, where its Portuguese translation significantly influenced Brazil’s coffee culture. Laborie’s book also reached Cuba, where a publisher there translated it into Spanish. As the nineteenth century progressed, Laborie’s book spread as far as the British colonies of Ceylon and India. Laborie had written the equivalent of an eighteenth-century New York Times Best Seller.

Because of its fame and widespread distribution, Laborie’s book is readily accessible online and at many libraries. A quick WorldCat search reveals dozens of libraries across the world have physical copies, and most of the editions are fully digitized. However, the 1845 edition, printed in Ceylon, does not share the accessibility of the other editions. There is no digitized version, and I have only been able to find two physical copies. One of them is, coincidentally, at the Perry-Castañeda Library. Boasting torn pages, damaged bindings, and held together with several pieces of Scotch tape, UT’s edition looked every bit like a 175-year-old book that had, quite literally, traveled around the world. After I first discovered the book in the fall of 2019, my form of preservation work was keeping it locked away in my desk drawer, where even I rarely consulted its contents. It was not until the Theory & Practice of Digitization Community Symposium that I gained the knowledge, and the courage, to take concrete steps for the book’s preservation through digitization.

Along with being exceedingly rare, this particular edition perfectly lends itself to digitization because it provides a fascinating window into a globalized network of knowledge circulation from the late eighteenth to the late nineteenth century. The number of editions and their geographical spread allow for a comparative study to trace how Laborie’s work changed, or did not, over time and in different geographical contexts. Using OCR (optical character recognition) and text mining methods on the newly digitized 1845 edition, I uncover the genealogy of knowledge contained within Laborie’s work. I highlight how little that knowledge changed in the approximately 50 years that separated the original from the Ceylon edition. Besides a new three-page preface, three short appendices, and different formatting, the Ceylon edition is identical to the original. Even Laborie’s footnotes from his 1798 edition persist within the 1848 edition. The digitization of the Ceylon edition of The Coffee Planter of Saint Domingo increases the accessibility for an otherwise nearly inaccessible work. It also provides a means for scholars to apply digital methods to uncover a global network of knowledge development and dissemination.

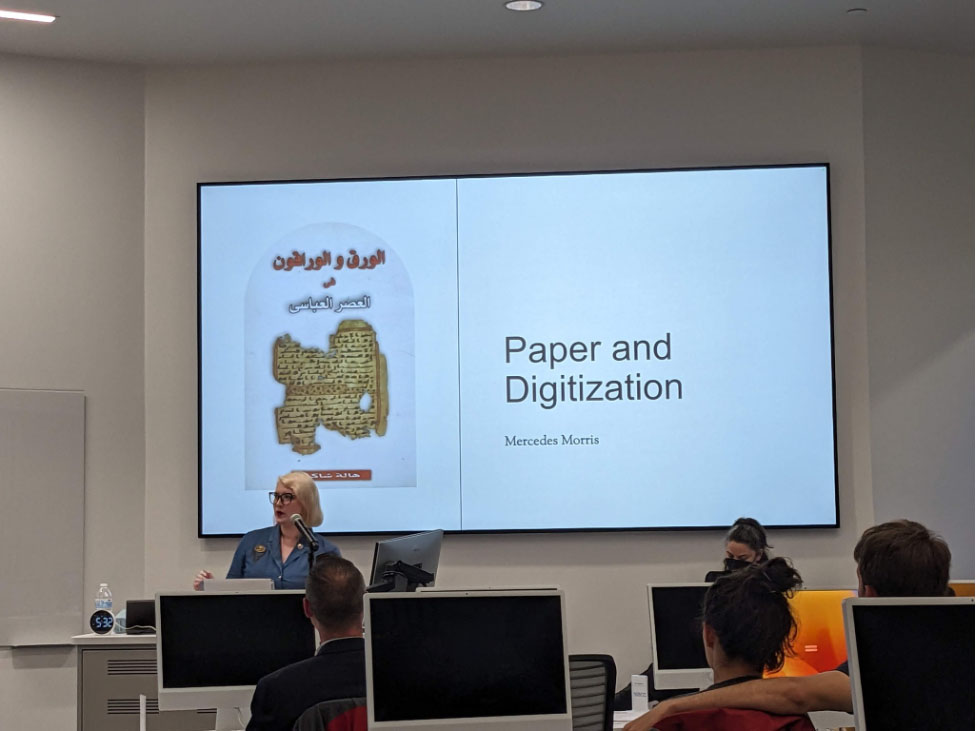

Mercedes Morris (Dual master’s degree student, iSchool & Center for Middle Eastern Studies)

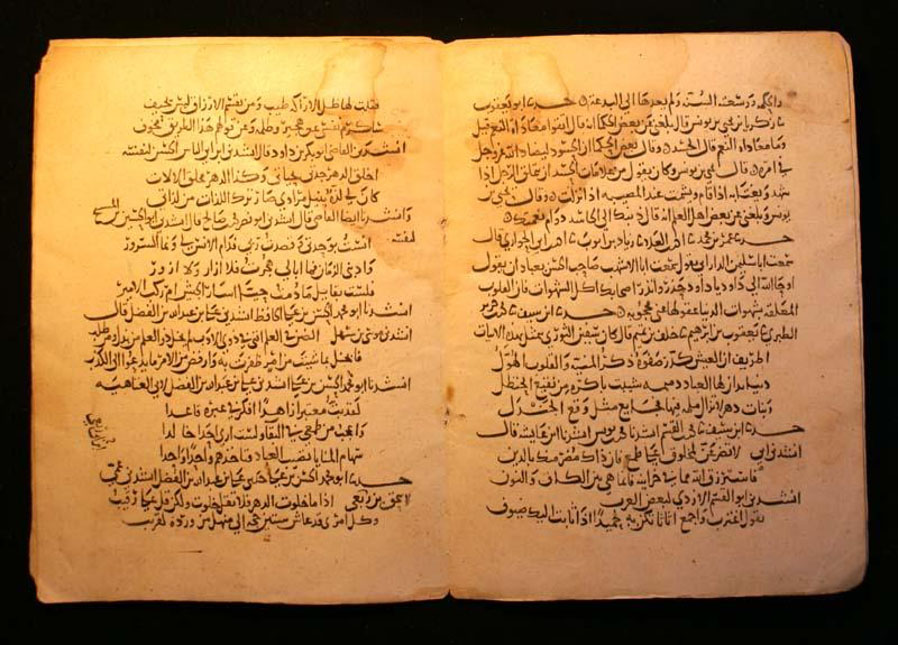

I am a student in Middle Eastern Studies and Information Sciences, with a focus on paper preservation. During this symposium program, I worked on digitizing al-Waraq wa al-Waraqun fi al-Asr al-Abbasi, a book on paper in the Abbasid Era. The Abbasid Era is an important era in Middle Eastern history for the rapid increase in written works due to the new technology of paper. There are many myths attested to explain the transfer of papermaking technology from China to Iraq, but these are not verified, and papermakers of the Abbasid Era quickly made this technology their own and quickly built on it, with improvements from these papermakers making their way back to China.

While digitizing this book and reading through it about the history of paper and papermakers in the Abbasid Era, the parallels between the new technology of the Abbasid Era–paper, in this case—and the digitization technology of the present day became clear to me. Paper, like digitization, allowed for increased access and production. Paper, even as a new technology, was cheaper and less labor-intensive to produce than papyrus and parchment, allowing more works to be produced and disseminated. Digitization also allows for greater access for people around the world to physical, written materials today, including rare documents and documents too fragile to be handled.

While written history, recordkeeping, and literary works have been around for several millennia, paper offered both the lightweight quality of papyrus and parchment with the permanence of clay tablets, all of which had been used in the area between modern-day Iraq and Samarkand that became known for paper technology and manufacturing. Clay tablets, while more permanent and also less sensitive to humidity than papyrus and parchment, were cumbersome and heavy. Ink could be easily erased by scraping it from papyrus and parchment, allowing for contemporaneous and much later changes to be made to documents almost invisibly and allowing for the erasure of certain histories.

Paper often has sizings applied, which are substances applied to paper to change the absorbency. Even with sizings applied to prevent too much ink being absorbed, paper would tear before the ink could be successfully removed, leaving evidence of attempted manipulation. This is because paper, even with sizings, absorbs ink; whereas ink sits on the surface of papyrus and parchment.

Now materials like papyrus, parchment, paper, and anything else that anyone would want digitized, can be subjected to sophisticated digital manipulations that cannot be discerned easily, bringing the issues of papyrus and parchment back to paper. On physical paper, even with the use of graphite, erasures and changes are still often visible. I suggest that perhaps the future of digitization lies in the metaphorical properties of paper that allow changes to be made visible to better track history.

Miriam Santana (PhD student, Department of English)

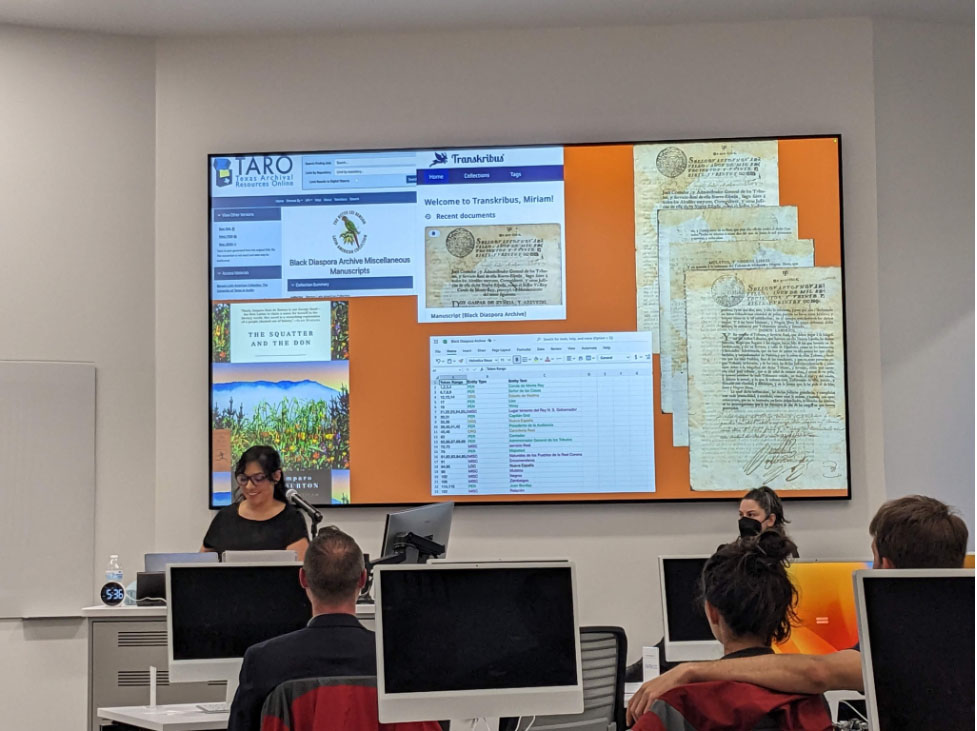

For this semester, my project has focused on recovering the presence of black people and characters in early Mexican American literature by placing them in critical conversation with colonial archival manuscripts. This was my attempt to imagine Black life as more than what these novels give us access to. Now that’s not to say that these colonial archives don’t come with their own silences and omissions, but my goal is to supplement these novels with other written texts. Where is black life in a Mexican colonial context? Voice? Body? Name? And location?

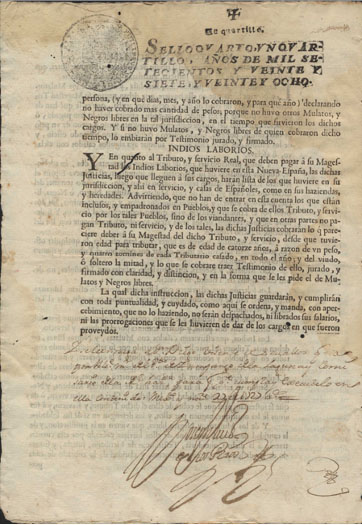

I chose manuscripts from the Black Diaspora Miscellaneous folder for their content, but also because they make a reasonably-sized collection. The selected manuscripts are documents by the Spanish crown that required all free people of African descent in colonial Mexico to pay a tax based on their African ancestry. It was the first time I worked with archival material that had yet to be digitized. I wanted, in the span of the semester, to choose something that was feasible and that wasn’t overwhelming. My research process following the following steps:

- Digitize the selected manuscripts using a flatbed scanner. The scanner turned the manuscripts into PDF files.

- I used Transkribus to apply optical character recognition (OCR) to the PDF. I used a model, created by LLILAS Benson digital scholarship coordinator, Albert Palacios, to perform this OCR.

- I took the text and inserted it into a Word document. In that Word document, I removed numbers and corrected for dashes, so that I was only left with the bare text.

- I used NameTag. NameTag is an open-source tool for named entity recognition (NER). NameTag identifies proper names in text and classifies them into predefined categories, such as names of persons, locations, organizations, etc.

- I took that table of information and entered it into an Excel spreadsheet, which resulted in a dataset of names and locations of people rendered in the manuscripts.

In a future project, I aim to follow the same process, with all of the manuscripts in this collection. I hope that it will result in a large dataset of names and places spanning the 18th and 19th century. I plan to create metadata for this collection and use the dataset to create a StoryMap. My hope is that this map represents the lasting and enduring presence of black life in these Mexican colonial archives. Below are some lingering questions that I will continue to think deeply and critically about:

- What are the ethical ways of working with these colonial documents?

- How do we then think about representation in a way that is ethical?

- How do I make sense of my own bias and desire to represent?

- How do I think about consent when the people who are in these collections are not alive to give consent?

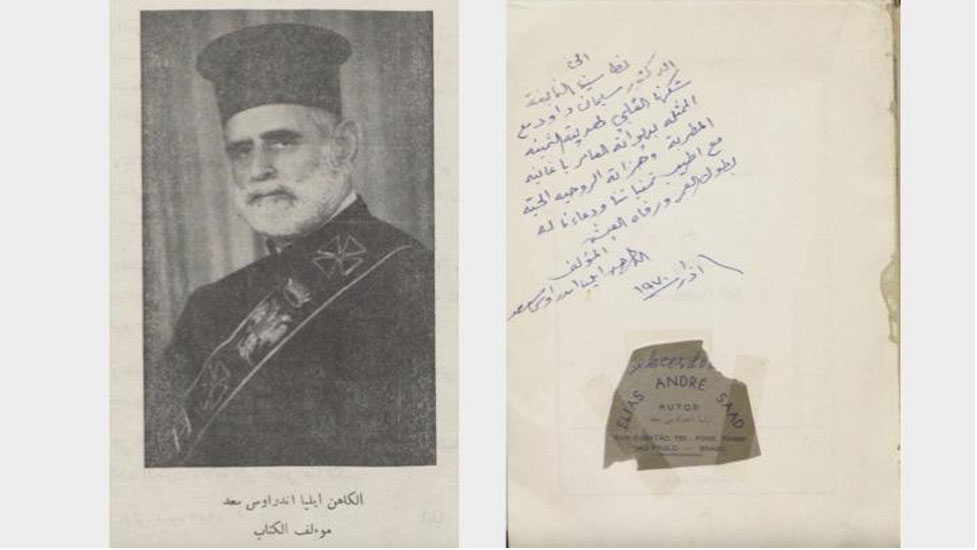

Natalya Stanke (Dual master’s degree student, iSchool & Center for Middle Eastern Studies)

In our first symposium session as a cohort, we unpacked the term “digitization” to understand the various facets of the digitization process. Taking an iPhone snapshot or scanning a document in a flatbed scanner can be useful; however, it’s ultimately only one step in the entire process of digitization. It’s important to keep in mind the many layers of labor involved from physical examination, image capturing, file processing, metadata description, repository ingestion, and more. It’s also important to continually learn about how to approach workflows of digitization both thoughtfully and equitably.

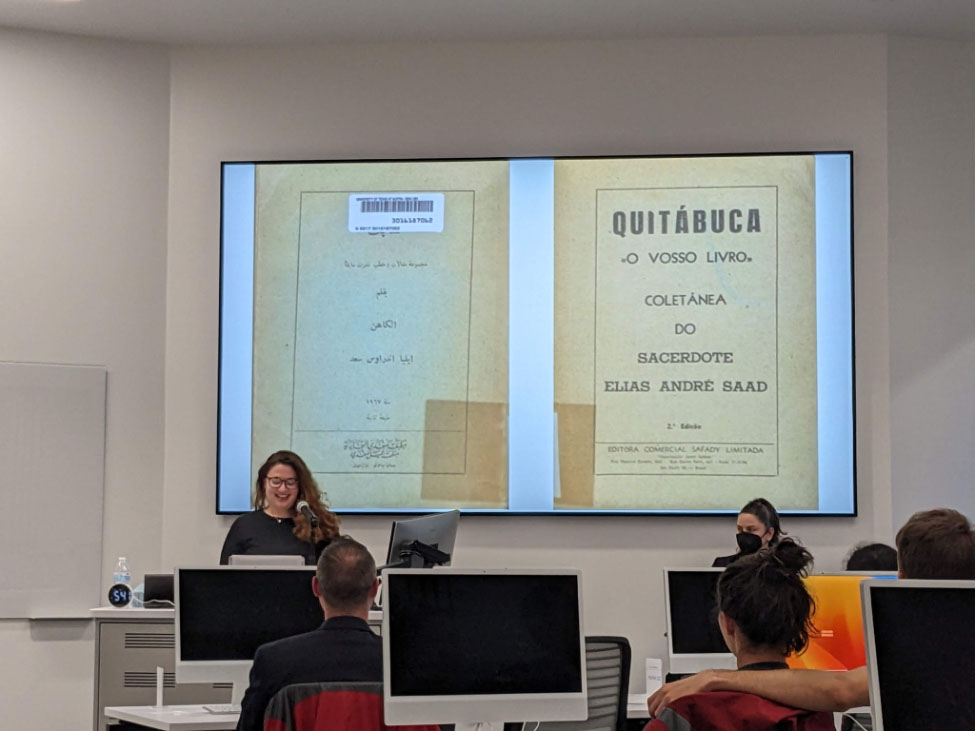

For this symposium, I chose one book from UT’s library collections and imagined how I would approach this item in a professional setting for digitization. My book is titled Quitábuca or “Your Book” from the original Arabic. It was written by a Syrian priest living in an Arab diaspora community in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The book is written in Arabic and consists of a collection of personal essays, published articles, letter correspondence, and opinion pieces from a variety of publications around the world. It contains biting commentary on French colonialism in the Levant, personal stories about immediate family members, guest author pieces discussing politics, organizing documentation for civic diaspora groups, and more.

- First, current American/English-language standards for describing diverse materials with global interconnectedness are insufficient at capturing the richness of the material reflected.

- Second, multilingual metadata is the future! Multilingual English/Arabic description (or Arabic/English/Portuguese, in this case) for materials like this book need to be prioritized for institutions seeking to maximize equity of digital dissemination when publishing collections online. I understand this is massively labor-intensive, but limiting the vast majority of rich metadata to the English-speaking world limits the discoverability and accessibility of many relevant materials.

In particular, the interconnectedness of different geographic and cultural regions sparked my curiosity about how to describe this book with useful metadata. When contemplating the description portion of digitization, I ended up with two major (and related) takeaways:

There are organizations building digital collections that serve as great examples of how to approach incorporating multilingual metadata. Two examples that inspired me in particular are the Digitization Project of the Memory of Arab Immigration in Brazil from the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik and the Arab Brazilian Chamber of Commerce, as well as the Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies at NC State.

Overall, this was a fun exploration for thinking through professional challenges in digitization and how labor-intensive, but important, it will be to include multilingual and multicultural approaches to my future work in librarianship.