Zines at the University of Texas Libraries

What costs approximately five dollars but can be considered rare ephemera in academic libraries? Zines, of course! We three (Daniel Arbino, Gina Bastone and Sydney Kilgore), who work with zines, hope to share our enthusiasm for the format in this quick overview, as well as three exhibitions during the coming year. In explaining the who, what, when, why, and where of zines on the UT Campus, we hope to capture your imagination and get you as excited about zines as we are.

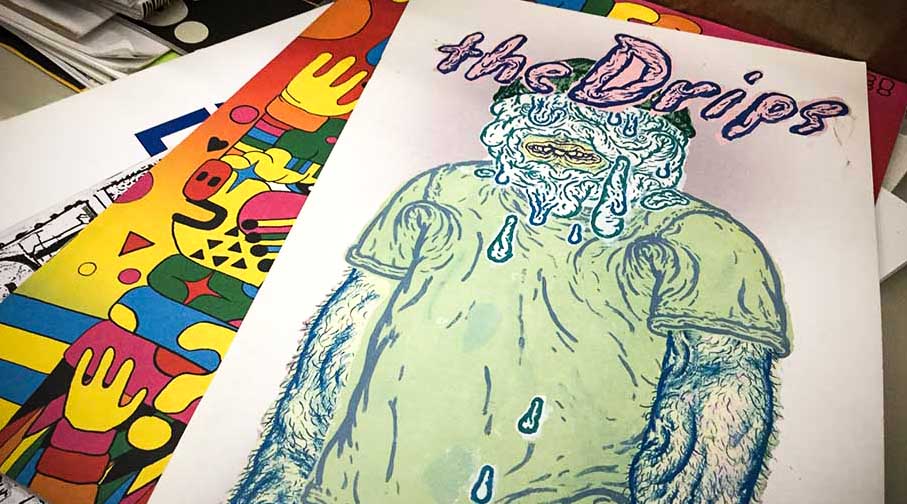

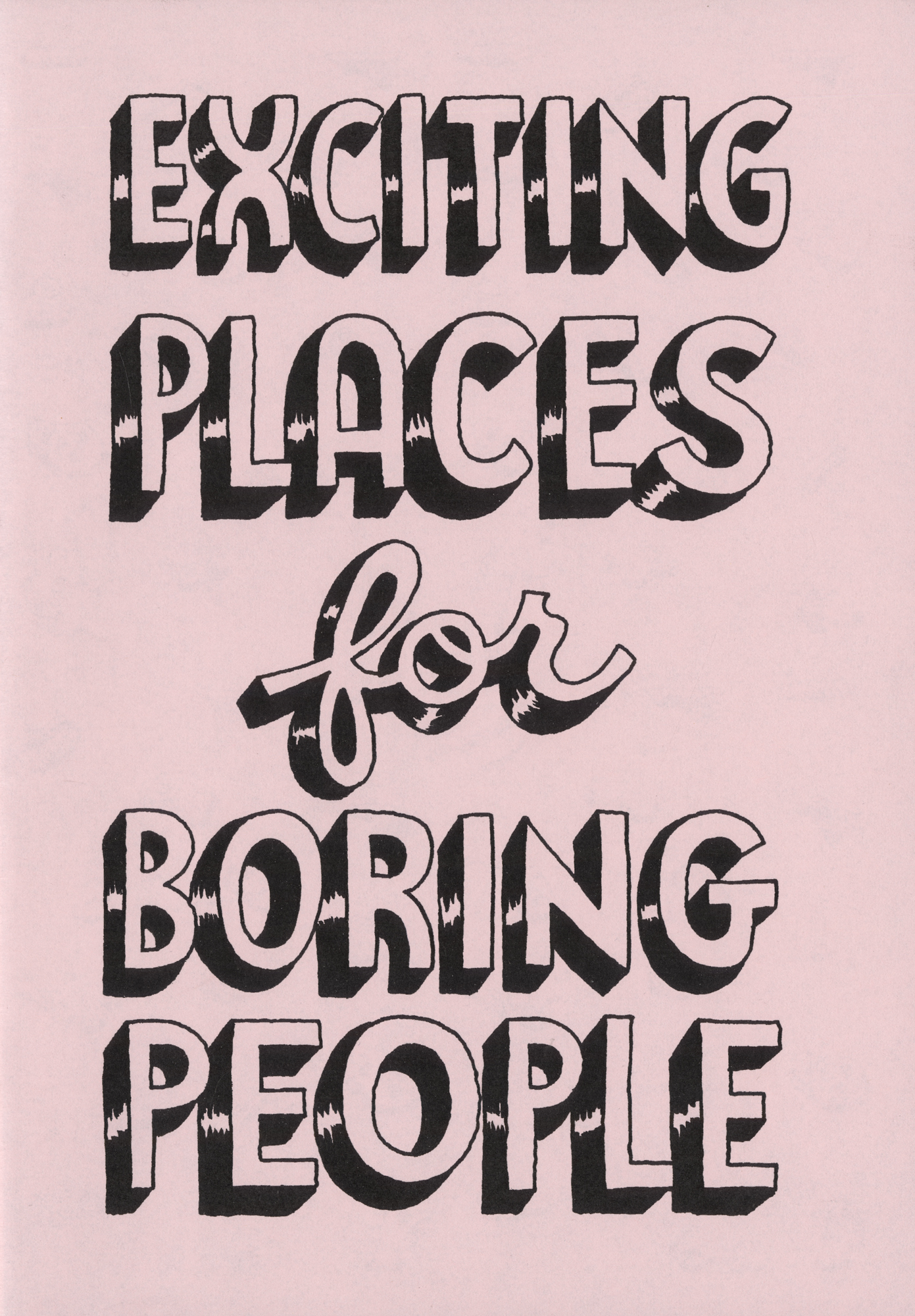

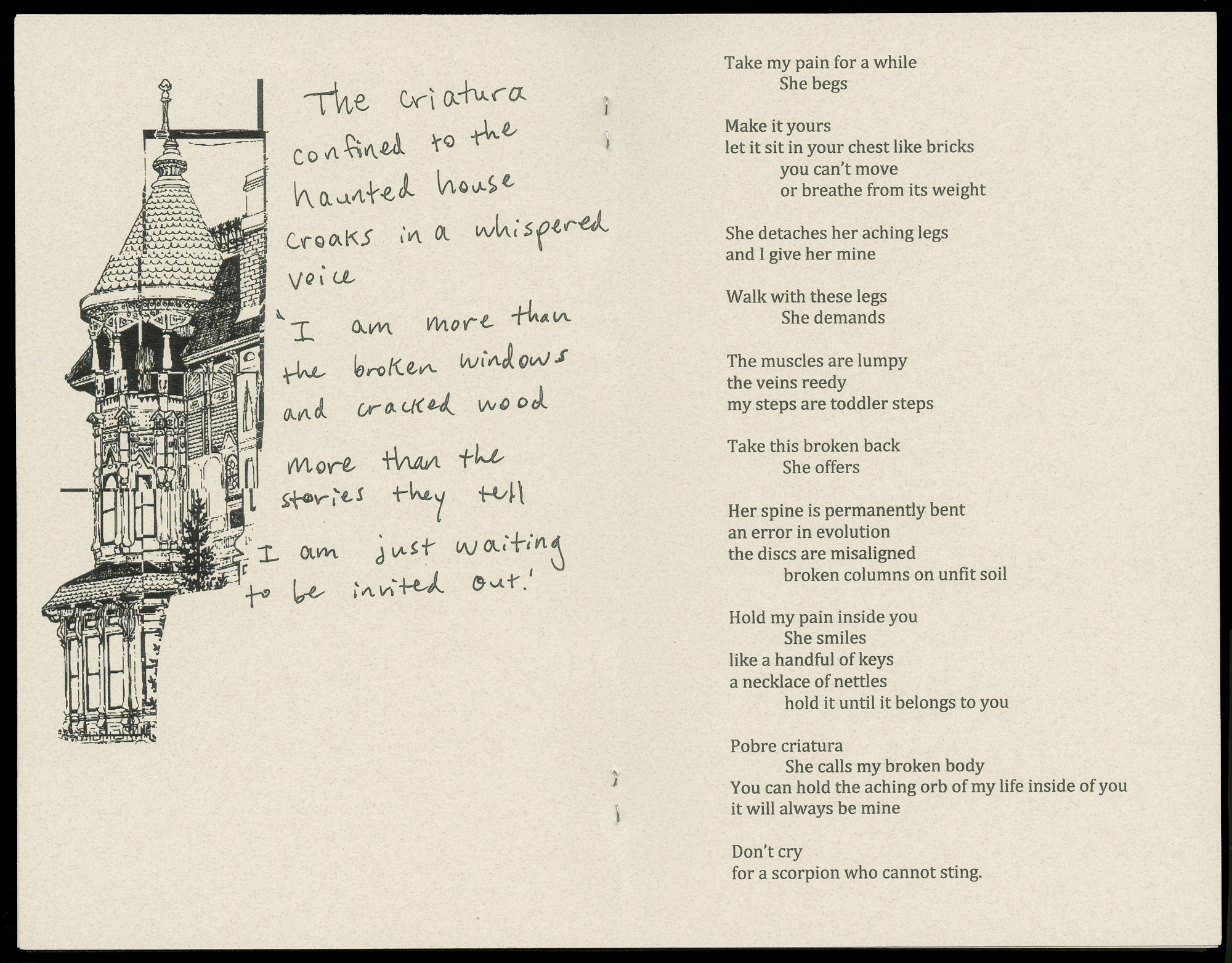

What do zines actually look like? Think of the appearance of all the instruction pamphlets you have ever received that accompany all the objects you have ever bought, and you will get some idea of the many ways zines can look. And like these enclosed sets of instructions, zines are most often staple-bound pages of images and texts that are light to hold, easy to flip through, with subjects galore.

The OED states that zine is a shortened form of the word fanzine, a term coined by a group of ”makers” that created handmade publications for their fellow science fiction fans in the 1930s. This same zine format – small circulation, handmade, often self-published – was picked up as a way of publishing social and political views in the 1960s by activists, then in the 1970s-1990s by punk rock and feminist groups. During subsequent decades the number of people making zines has grown huge, with a resultant rise in the number of zine formats and subjects. Which brings us to the present and to thoughts the three of us have about zines and the zine collections housed in the UT Libraries’ Collections.

What is a zine?

Gina Bastone: My gut-response to this question is that a zine is a just photocopied, staple-bound booklet. Most are really that simple, but at the same time, this flexible format is a vessel for anyone – and I mean, literally anyone – to have a voice. That means zines can be as varied and diverse as their creators, which also makes them difficult to define and categorize. Zines don’t cost a lot to make, and they’re accessible, portable, and easy to share. For writers and artists, creating a zine provides a way (outside of mainstream publishing) to put creative work out into the world, and for activists, zines are an effective and low-cost way to spread important information and mobilize others.

Daniel Arbino: This is something that I’ve been trying to pin down for the last few years. In my estimation, a zine is a do-it-yourself publication that historically, has had a very small audience of family of friends. It can include art, photographs, poetry, short essays, or stories. I often think of those materials as highly personal, whether it is the creator’s reflection on their own life or a television show or music genre that they connect with on a deep level. Nowadays, zines can reach larger audiences through online purchasing on Etsy or through zine fests. However, the explosion of zines through these outlets has also made their identification murky for me. Sometimes a self-published graphic novel can look like a zine and vice versa.

Sydney Kilgore: I, like Daniel, have struggled with what defines a zine. Yes, there is the handmade aspect to them or their suggested small circulation number. Zine texts and images are also usually original to the artist. But zines can contain text and images appropriated by the artist as well. Pages in zines can be stapled together in the simplest way or can approach the artist book category in their complexity and beauty. Zines can be self-published or not. They are usually reasonable in price when initially bought, but, with time, can become rare and attain Special Collection status. In truth, I think the inability to easily define what zines are add to their mystique. People want to know about them, and interested, they go to zine fests, meet the artists, look in libraries and books stores and learn what can always be said about zines – they are limitless in their formats, subjects, and appeal.

What is your personal history with zines?

Sydney Kilgore: Zines escaped my notice until I started working in the UT Fine Arts Library (FAL) and learned of the Zine Collection that my boss, former FAL head librarian Laura Schwartz, was building. Her enthusiasm for zines was contagious. I recall one UT Library event, a Zine-A-Thon, Laura organized during which a group of PCL catalogers first explained the perils of cataloging zines – not easy to assign subject headings; numerous contributors with unclear roles; no listed publishers or publication dates; and so forth. Then we attendees attempted to crowdsource-catalog three zines of our choice from the amazingly diverse UTL collections of zines. We ran out of time to complete our cataloging, feeling some sympathy for our cataloguer colleagues. About a year later, armed with limited knowledge and inspired by Laura’s proselytizing, I headed for a conference in Seattle, where I bought my first zine from the famous Seattle bookstore, The Elliott Bay Book Company. I remember grinning as I left the bookstore. I was now one of the Zine initiates.

Gina Bastone: I first discovered zines in college, when friends of mine created staple-bound booklets to showcase their creative writing projects. Back then, it was just a fun thing a few friends did to circulate their writing to a small audience of peers. I didn’t really think much more of it, and I didn’t know anything about the history of zines in punk culture or the Riot Grrrl movement. When I was in my 20s, I learned more about those punk, feminist roots, and I contributed my own writing to more sophisticated art/poetry zine anthologies. I also started collecting poetry chapbooks at public readings. I’m fascinated by the connections and similarities between zines and chapbooks, and why some writers use one term over the other. The “chapbook” as a format has been around for hundreds of years and has its own interesting evolution. But at its heart, a chapbook is a lot like a zine – it’s a simple, low-cost mechanism for sharing creative work outside of mainstream publishing.

Daniel Arbino: I wish that I had my own zine growing up, but alas, I only discovered zines about three to four years ago. I was working on my MLIS at the time and living in New Orleans. For one of my course assignments, I went to the Amistad Research Center and used their zine collection. I was immediately struck by how unique each zine is. Whether it is by shape, size, format, or content, it seems that every zine carries a distinction. The fact that the zine is an outlet for historically marginalized groups captivated me most of all. I thought, here is a chance to incorporate voices that publishers are overlooking. When I started at the University of Texas at Austin, that sentiment contributed to my desire to advance the Benson Latin American Collection’s zine offerings.

What is the University of Texas Libraries’ institutional history with zines?

Daniel Arbino: Speaking for the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, I can say that adding a zine collection was perhaps new in name, but not in practice. We are the official repository for the Puro Chingón Collective, who regularly publishes their own zine. Additionally, my colleagues and our predecessors at the Benson have collected a plethora of DIY and small press publications from across Latin America – Caribbean graphic novels, Brazilian cordeles, Argentine chapbooks, and cartoneras. Curating our zine collection to match these similar materials has been a project of mine for two years. In that time, I have purchased approximately 200 zines focusing on U.S. Latinx creators through zine fests in Austin, Albuquerque, San Antonio, and New York City as well as online acquisitions. In the Spring of 2019, I processed these zines as an archival collection that can be accessed in our Rare Books and Manuscripts Reading Room. The collection is a small, but noteworthy addition to UTL’s commitment to popular culture.

Sydney Kilgore: The Fine Arts Library’s Collection of zines began to grow in earnest in 2012 under the stewardship of former FAL head librarian Laura Schwartz. Laura, fascinated with zines, wanted to build a collection that could be shared with library patrons; the reasonable cost of zines making their collecting possible. She set her collecting parameters – art and music, and/or local and regional artists; and frequented Austin stores such as Domy Books, owned by zine collector Russell Etchen. This relationship later resulted in Etchen gifting his Zine Collection to the FAL. Laura also worked with knowledgeable library colleagues like Beth Kerr, former FAL Dance and Theater Librarian, and Katherine Strickland, PCL Maps Coordinator, who shared their knowledge and made their own additions to the FAL Zine Collections. Laura then made the decision that the zines be searchable in the library catalog and available for checkout. Former Arts and Humanities Liaison Librarian Becca Pad, equally enthused about zines, continued to make additions to the FAL Zine Collection; wrote a LibGuide for them; and helped head the UT Libraries’ participation in the immensely popular Lone Star Zine Festival. Thanks to Becca’s vision, there are now also plans for a new zine exhibition space on the 5th floor of the FAL which will focus interest on these unique collections.

Gina Bastone: When I started at UT in 2016, I knew about the Fine Arts Library’s zine collection, but I figured I wouldn’t work with it too much because I’m based at the Perry-Castañeda Library. However, I oversee the Poetry Center collection, which was founded in the 1965. I quickly learned that the Poetry Center has a wealth of poetry chapbooks, some published as far back as the 1950s. I found a chapbook published in the 70s by a Tejano activist-poet. It has cut-and-paste images interspersed with lines of poetry, and I thought “Is this a zine? Is it a chapbook? Is it somehow both?” And that’s the fun of the Poetry Center collection – it has these treasures, some of which are pretty rare, that document a history of creative writing in Texas entirely outside of mainstream publishing. I’m proud that the UT Libraries is able to preserve these little books and make them accessible to readers!

Over the next few months, we will be rolling out three different digital exhibits that highlight zines and chapbooks from UTL collections. In the meantime, be sure to visit our table at the 2019 Lone Star Zine Fest from 2-8pm on Sunday, September 1st at Northern-Southern Gallery on 1900 E. 12th St. We will be answering questions about zines, showing off a small sampling of our collections, and even handing out a zine that we made ourselves.