Earlier this year, the UT Libraries hosted a panel discussion called, Can I Use That?: Remix and Creativity. The event was the brainchild of Juliana Castro, a graduate student in the School of Design & Creative Technologies. She worked with librarians Becca Pad, Gina Bastone and Colleen Lyon to plan a panel event that dove into issues around rules of copyright and reuse as they relate to creative fields of inquiry.

The panelists for the event included: Dr. Carma Gorman, Design; Dr. Philip Doty, School of Information; Dr. Carol MacKay, English; and Gina Bastone, UT Libraries. The question and answer session of the panel was particularly lively as participants engaged with our experienced panel on a variety of reuse issues.

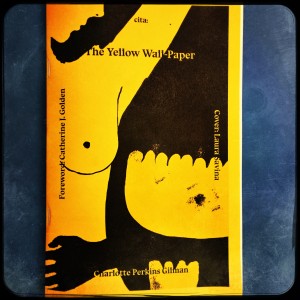

The capstone of the event was an opportunity to bind a Cita Press public domain book, The Yellow Wall-Paper, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. UT Libraries is pleased to work with scholars like Juliana Castro who are interested in exploring new ways to freely share information, and is excited to help her introduce Cita Press.

BACKGROUND

Public domain is a legal term used to refer to visual or written works without intellectual property rights. Works enter the public domain for different reasons, including expiration of the rights, forfeiture, waiver, or inapplicability, as in the case of pieces created before an existing legal framework. At the end of the eighteenth century, copyrights lasted only 14 years in the USA, with an option of renewing for another 14 years. However, copyright terms have expanded dramatically over the course of the twentieth century in the USA.

Since the passage of the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act of 1998, most copyrighted works do not re-enter the public domain until 70 years after the death of the author. These extensions are created to benefit creators’ interests, but not only do they oftentimes fail to do so, but can stifle creativity, free speech, and the democratic exchange of ideas.

In the last three centuries, women have gradually made their way into the publishing industry as active writers, often exploring topics considered inappropriate or even immoral for women to address. The printing press was developed by Johannes Gutenberg c.1439. By 1500, printing presses were operating all throughout Europe; by 1539 Spanish colonists were printing in Mexico; and by 1638 English colonists were printing in New England. However, until the early nineteenth century, writing was still a suspect occupation for women. Because often times writing was viewed as unfeminine, the few women who had the educational background to write works of public interest would often publish anonymously, using masculine pseudonyms to avoid jeopardizing their social status.

Art and literature have been sexist arenas, and as Joanna Russ points, for centuries women have had to fight outright prohibitions, social disapproval, lack of role models, isolation, and other forms of suppression in order to get their work published and recognized. Most of the nineteenth century’s feminist literature is now in the public domain, but many of these writings are not being republished by commercial publishers. When publishers do reprint public-domain texts, they rarely do so in open-access book formats. Because commercial publishers invest in curating and marketing well-designed collections of reprints, they frequently commission original annotations or introductions from scholars, which in turn enables them to copyright and profit from their new editions.

In contrast, Internet-based archives such as Google Books, HathiTrust, and Archive.org make an enormous corpus of public-domain books available for free online, but do so as scans or in poorly designed digital formats. Moreover, internet archives usually do not make their collections particularly navigable or appealing to non-scholarly audiences, nor do they make it properly designed and easy to print.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Cita’s purpose is to celebrate and make accessible the work of female authors, and inspire people to explore open publishing formats. In the future, I plan to extend Cita’s reach as an active open-source editing platform that is committed to intersectionality and that welcomes diverse voices and backgrounds by republishing new works, especially in Spanish, including those of living authors who are willing to open-license their works.

As is the case with most successful open-source projects, Cita needs user-contributor engagement in order to grow. The existing collaborative community is likely to extend their work towards creating new material, and potential new contributors will be encouraged to join in at different levels of the book-creating process, including cleaning texts, reformatting HTML, designing covers, laying out texts, marketing the site, etc. I plan to apply for small grants that can cover certain parts of the book making process, such as formatting and free distribution of printed copies. But Cita’s success will ultimately rely on the efforts of those who are interested in celebrating and making women’s art and literature more accessible.

Please follow, join, contribute and share: citapress.org

Juliana Castro is a Colombian graphic designer and editor, and a graduate student in the School of Design & Creative Technologies at The University of Texas at Austin.