As we’re wrapping up Preservation Week 2018, it’s instructive to remember that at the core of the library mission, the act of preserving the vast collections of the University of Texas Libraries is one of the most important things we do. A lot of times this reality gets lost in issues of actual collection management or access issues, but this annual recognition established by the American Library Association provides an opportunity to highlight the exhausting and often overlooked work of preservation staff at libraries.

You may have seen an earlier story about the efforts of our intrepid staff’s foray into a storm disaster zone to recover items from the heavily damaged Marine Science Institute’s Marine Science Library at Port Arthur. It’s a great example of a dramatic response in service of emergency protection and preservation of important library resources. Almost every year, though, there are examples of less sensational acts of professional heroism that test the buoyancy of our incredible preservation staff. One such example occurred in the fall of 2017 — a short time after the Harvey rescue effort — when a shortcoming in a renovation project at the Jackson School of Geology resulted in a construction failure that would’ve represented a loss of hundreds of volumes were it not for the expertise and dexterity of our preservationists and onsite staff.

Over the summer of 2017, a lab renovation on the 5th floor of the Jackson Geology Building above the library took place. After hours on a Monday evening the following fall, a water line in the lab failed and water began to enter the ceiling over the stacks of the library, eventually leading to a collapse of ceiling tiles and what was described as water “gushing and pouring” onto the volumes below. Library staff followed protocols to involve emergency response staff and managed to get the water shut off, but by the time this had happened, almost 400 books had been directly damaged by the flow.

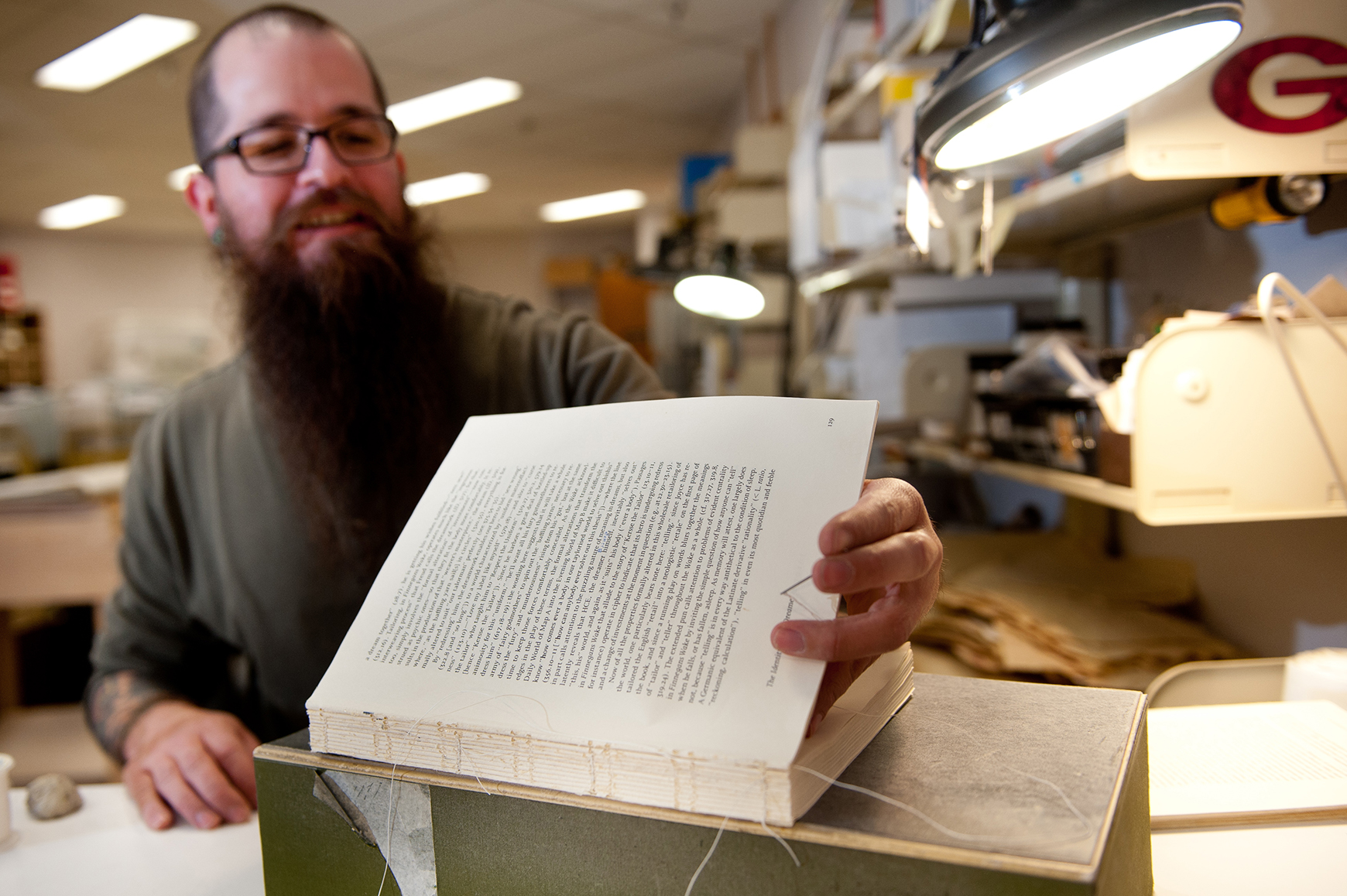

For many libraries across the country, this would represent a loss of resources, but the university is fortunate to have a library system that features a robust capacity for ensuring the long-term protection of the knowledge resources that have been built over its 130-plus year history.

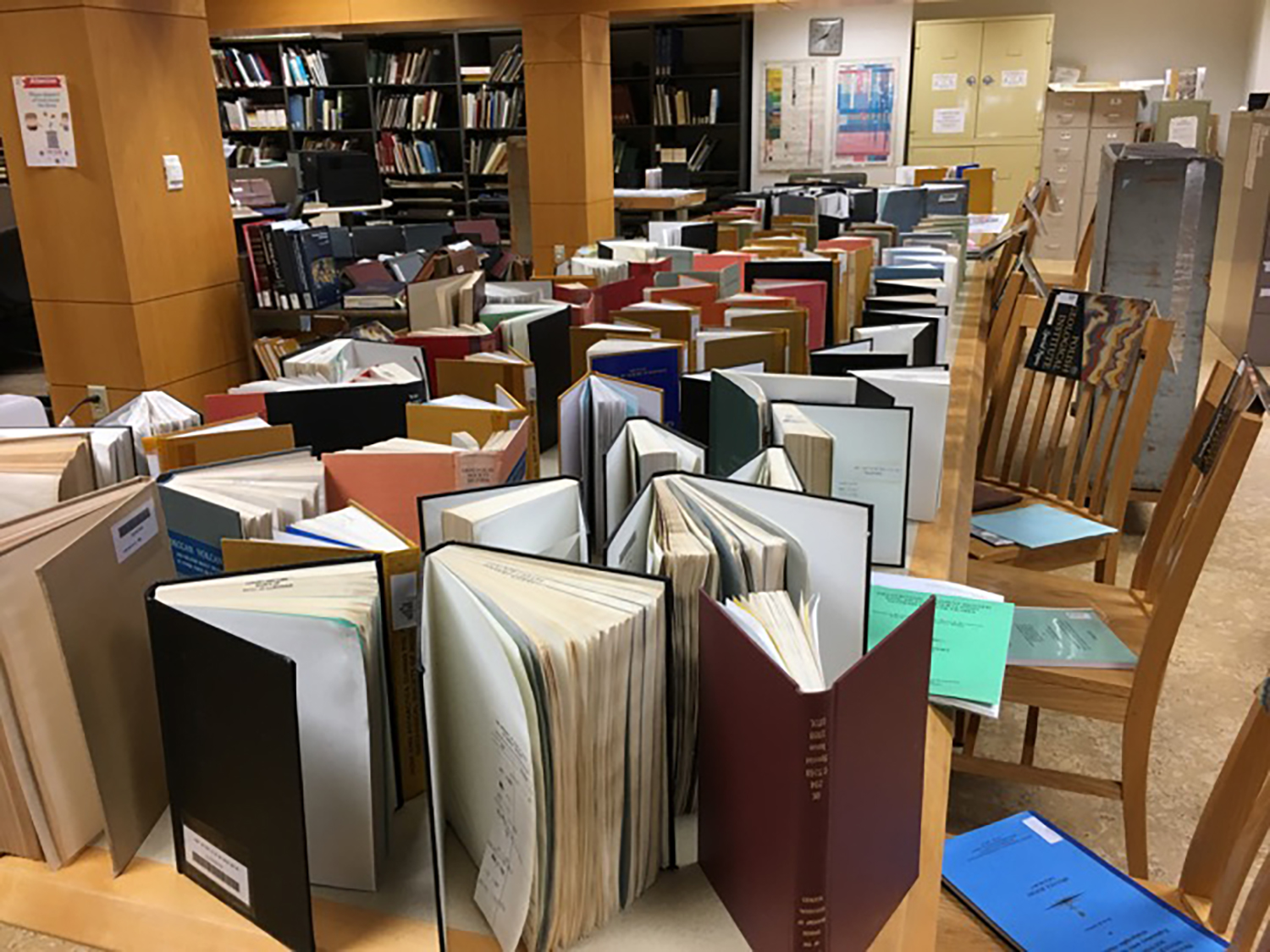

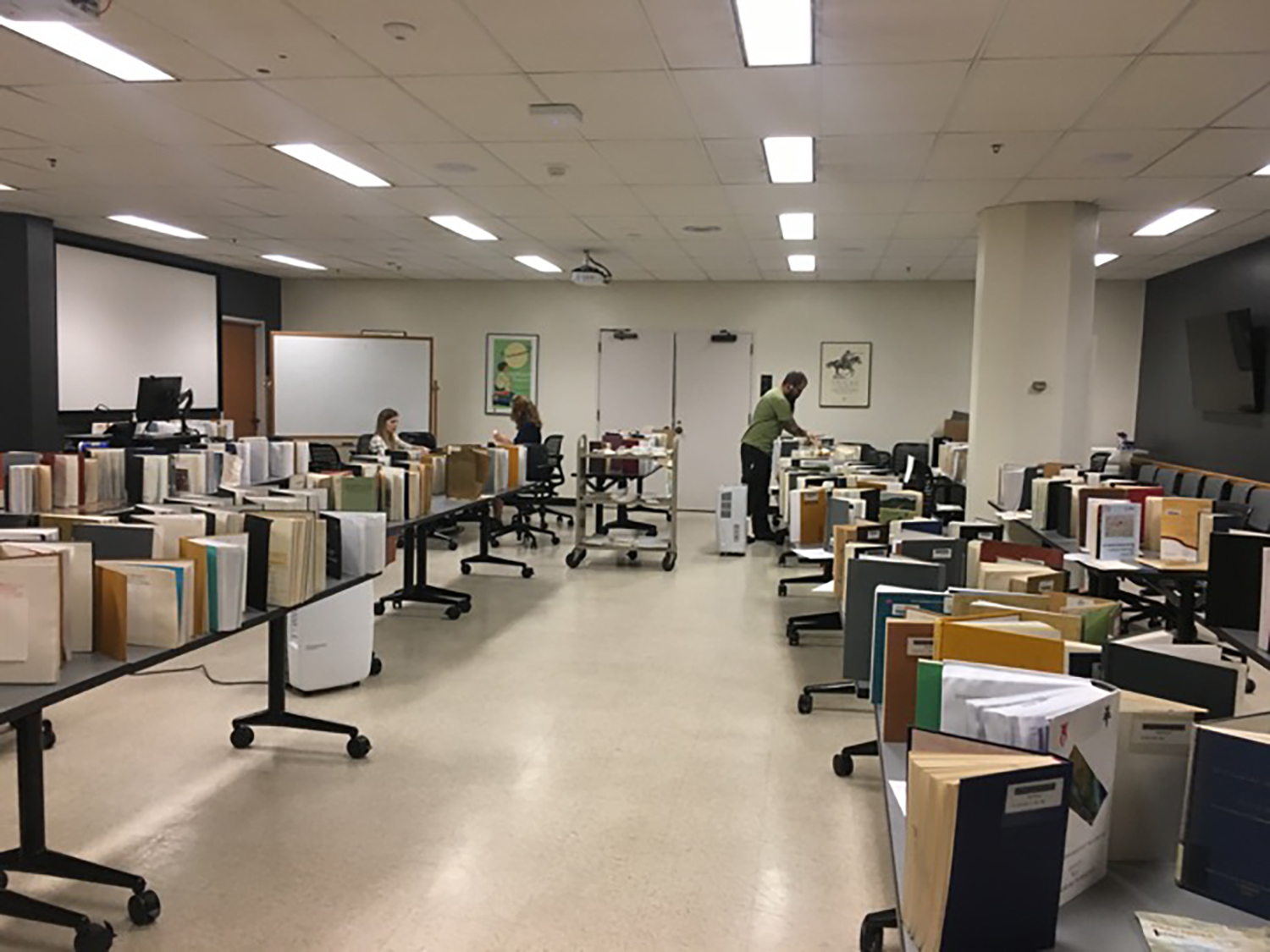

Staff response included immediate assessment of the materials and fanning out the most heavily-affected items on tables and staging industrial dehumidifiers and air circulators to address the water damage as quickly as possible, and some of these needed to be interleaved with additional blotter paper to absorb the appreciable moisture. Of the 394 items that were directly impacted by the flood, 35 required additional preservation attention, including repair and rehousing, and an additional 1200 items were removed from the shelves as a precaution, a not insignificant number that would need sorting, ordering and re-shelving after the cleanup.

In the course of the emergency, staff spent 24 hours on the initial response, 40 hours on recovery efforts (including transport and triage), and 10 hours of additional effort on coping with the additional preservation work needed to save the most heavily damaged books. And this doesn’t even take into account the work needed to return the library and its collections to the previous state that was undertaken by the onsite staff and facilities crew.

Preservation Week was established by ALA to highlight the need to think about supporting a function of the library that often goes unnoticed or underappreciated. Some 630 million items in collecting institutions across the United States require immediate attention and care. 80% of these institutions have no paid staff assigned responsibility for collections care, and 22% have no collections care personnel at all, leaving some 2.6 billion items unprotected by an emergency plan.

We’re lucky to have a university that provides for the expertise necessary to protect an investment in knowledge built over its long history, that can, as a result, serve this generation and many to come.