In observation of Open Education Week, UT Libraries is proud to spotlight a few of our talented faculty members who are on the forefront of the open education movement as open educational resource (OER) authors! Because we can’t limit ourselves to just one week, we’re excited to celebrate open education throughout the month of March.

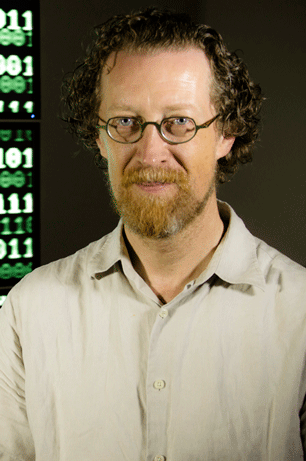

We’re starting this year’s series with Dr. Victor Eijkhout. Dr. Eijkhout is part of the Texas Advanced Computing Center, which he joined in 2005 as a Research Scientist in the High Performance Computing group. He conducts research in linear algebra, scientific computing, parallel programming, and machine learning. Before coming to TACC, he held positions at the University of Illinois, the University of California at Los Angeles, and the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

Dr. Eijkhout has authored open courseware, including several open textbooks and accompanying programs and code sets. Below, he generously shares his experiences developing OER with us.

Do you recall how you first became aware of open educational resources (OER) or the open education movement more broadly?

“In science, open software and open courseware predates the term ‘Open Source’ by a wide margin. In the 1980s I provided feedback on a tutorial document that someone on a different continent was making, and that proved very popular. In the mid-1990s I co-authored a computer science textbook for which we got the publisher (SIAM) to agree on a dual license: the book was for sale but also downloadable (including software) and viewable as web pages. In a similar spirit, I started writing my textbooks about 15 years ago without any awareness of being part of a movement. After I finished my first open textbook I did some searching and found the Saylor Foundation which develops OER. They licensed my book for what is probably a similar amount as I would have made from commercially publishing the book.”

You’ve developed a wealth of open courseware, including several open textbooks and accompanying materials like Introduction to High-Performance Scientific Computing; Parallel Programming in MPI, OpenMP, PETSc; and Introduction Scientific Programming in Modern C++ and Fortran. What inspired you to create these resources?

“These textbooks were written for courses that TACC teaches. (The Texas Advanced Computing Center provides a small number of academic courses in addition to many short trainings. These courses are – for historic reasons – provided as part of the SDS department.) When I was slated to teach a course, I searched for available textbooks, but usually I disagreed in some way or other with the approaches they took, so I started writing my own. In a way, writing a textbook, for me, is a form of self-defense: if I only prepare lecture notes, I will often find, standing in front of the class, that I miss details. By writing out everything in full paragraphs and mathematical derivations, I make sure I don’t overlook anything.”

What was the most challenging part of developing your own resources? Was there anything that surprised you?

“The challenge is in dotting the is and crossing the ts. As in most things, the first 80 percent is easy. Getting to a finished product is hard, which is why you find many more lecture notes online than textbooks. An example of what I ran into in my programming books is the challenge of making sure code is 100% correct, and corresponds 100% to the output given. For this, I developed a whole infrastructure of example programs, from which snippets are clipped to be included in the text, and similarly the output captured to be included side-by-side.

In this aspect, self-publishing the way I do, through downloads and repositories, has advantages over publishing commercially: you can release a product informally in an earlier stage and revise it more easily and more often.”

Do you use any OER developed by others as teaching resources?

“Not directly, but if I come across resources I will often peruse them to get inspiration, or even to ‘borrow’ bits for my own texts.”

How do your students respond to the resources you’ve developed?

“I wish I could say that they really appreciate it, but the reactions have a wide range. For many of course a textbook is just a textbook and it goes unmentioned. Some of them have delved into the literature and tell me my book is really good. On the other hand, in a sign of the times, students’ first reaction to problems seems to be to look online rather than in the textbook. Unfortunately, in programming this sometimes leads them to outdated material.”

What advice would you offer to an instructor who is interested in using or developing their own OER but isn’t sure how to get started?

“The threshold for open resources is low. Any lecture notes you put up for download will be found by the search engines. My advice would be to write what *you* need. If it’s useful to other people it will be found.”

Want to get started with OER or find other free or low cost course materials? Contact Ashley Morrison, Tocker Open Education Librarian (ashley.morrison@austin.utexas.edu)