Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the UT Libraries Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of, and future creative contributions to, the growing fields of digital scholarship.

One day when I was familiarizing myself with the history of Japanese Canadians, I encountered this lovely, small online exhibition. It is built on 36 PDF files of digitized letters selected from the Joan Gillis fonds, housed at the University of British Columbia Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections. The exhibition, beautifully titled “I know we will meet again,” tells a dark and brutal episode in Japanese Canadian history from 1942 to 1948.

The letters were written by young Japanese Canadians to Joan Gillis (1928–2019, more info on Gillis), a white teenage girl they shared elementary and middle school years with before being forcefully removed from their homes in British Columbia to various locations in interior Canada during WWII. Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the Canadian government seized fishing boats and confiscated cameras and shortwave radios owned by Japanese Canadians. In January 1942, the Canadian federal government passed an order to remove Japanese Canadians from coastal British Columbia. By March 1942, about 22,000 Japanese Canadians were dispersed to areas east of the Rocky Mountains and were not granted freedom until 1949. During their forced removal, the Canadian government also seized, confiscated, and sold Japanese Canadian properties left in BC, including lands, houses, farms, etc.

The letters detail the harsh childhood and teenage years that Gillis’ Japanese Canadian friends had to endure. All the letters in this exhibition have been scanned, transcribed, annotated, and geo-coded, thereby making it easy to explore the letters’ content by author, theme, location, and time.

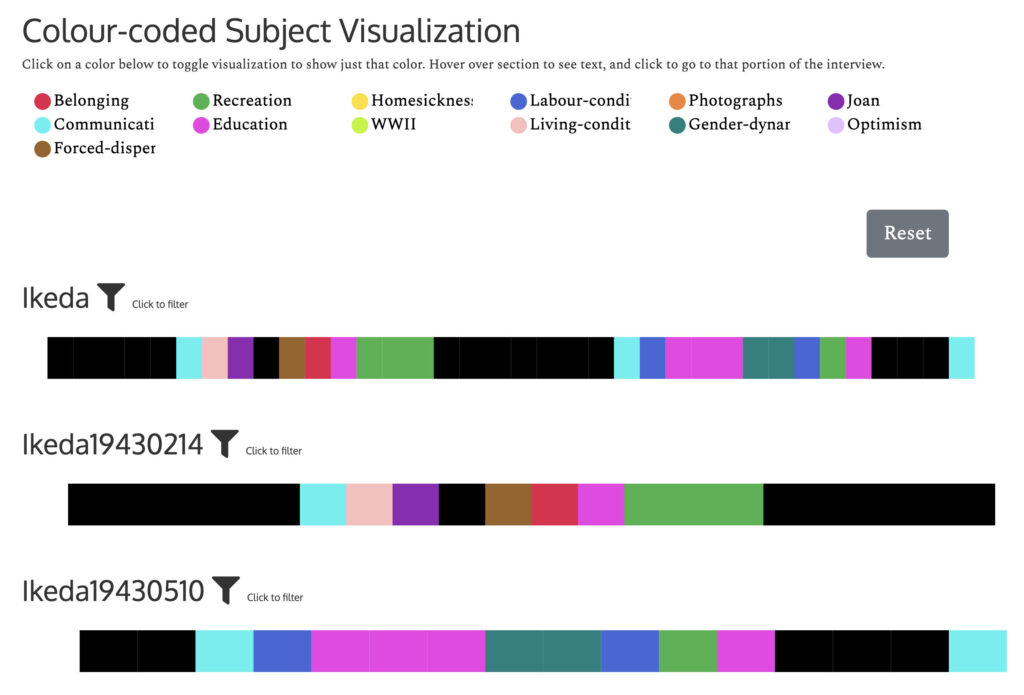

For example, when we choose to browse by subject, we are directed to a beautiful and effective visualization of the subjects discussed.

As a person with mild color vision deficiency, I have to commend the curators’ apparent thoughtfulness in making the spectrum easier to see. Click on the little colored circles, then the associated subject will be highlighted in each letter.

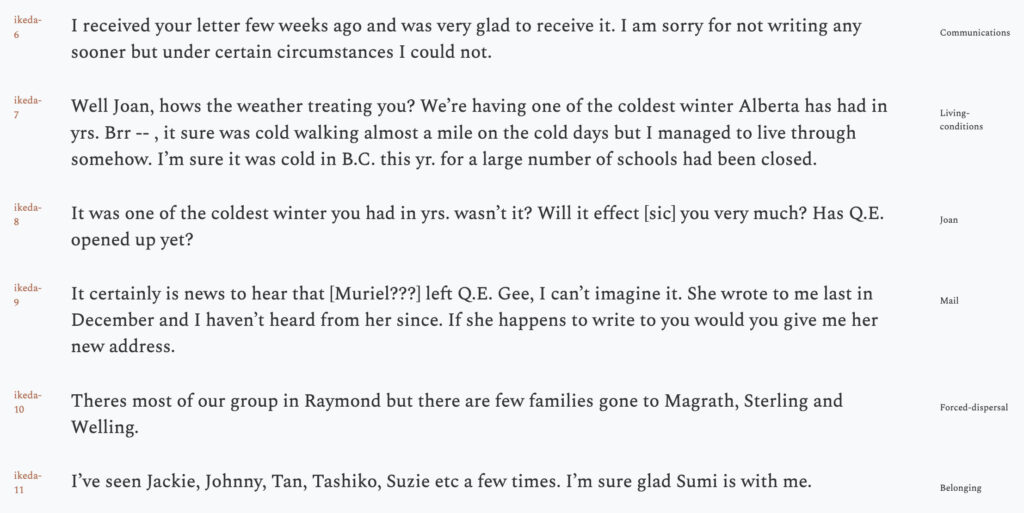

Likewise, one can open up a transcript and see every sentence’s annotated subject on the right.

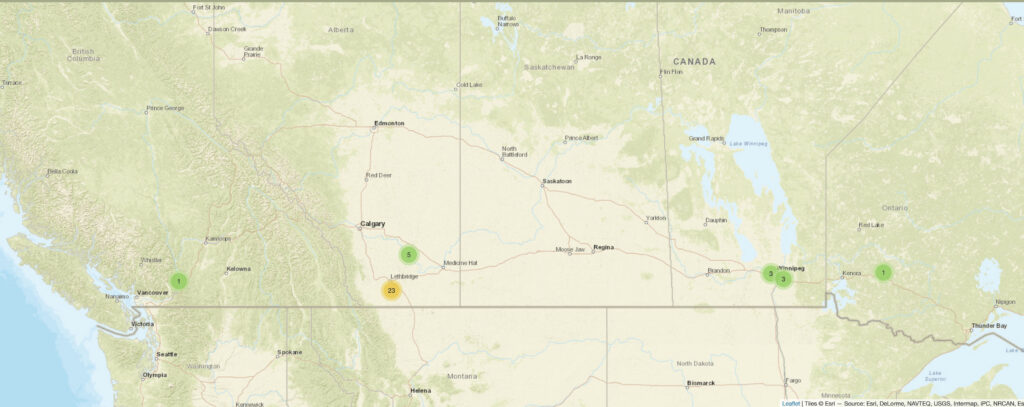

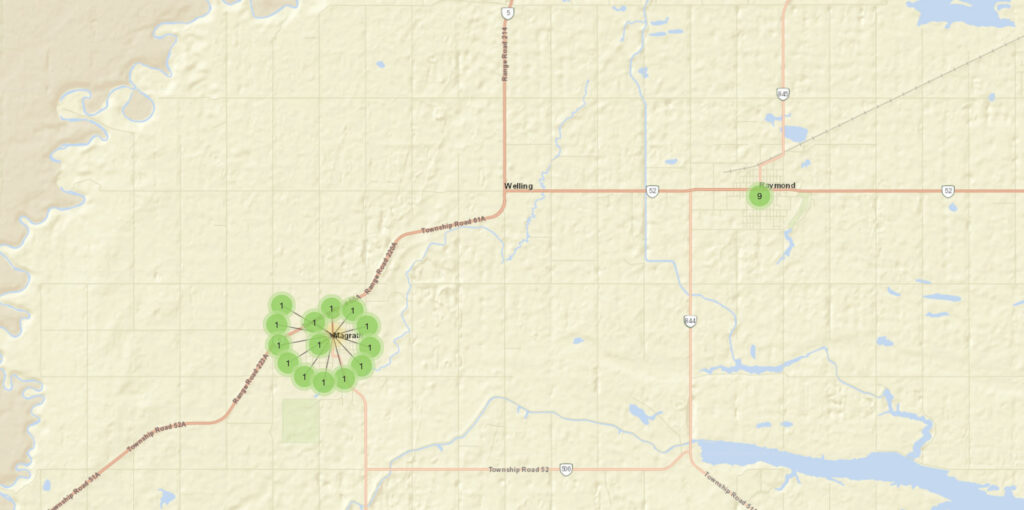

Maps help users grasp the extent of the dispersal of the letter writers as each letter is encoded with coordinates. One can zoom in and out to see the physical distance between the letter writers. One suggestion I would have is to mark Gillis’ location as well, just to give viewers a sharper sense of how far they have been dispersed.

The curators have enhanced the exhibition through suggested themes which include essays that reference snippets from the letters. These essays give historical contexts in which the letters were produced. For example, in the essay on “Communications,” the curators discuss how the correspondence between Gillis and her friends was censored by the Canadian authorities. Under “Labour,” one will find more information about sugar beets farming that many letter writers’ families “volunteered” to engage in, although the letters make clear this “volunteering” was the only option other than labor camps and the splitting up of families.

Last but not least, I love the notes under “About the Collection.” The Land Acknowledgement is specific and lists all Indigenous lands that are mentioned in the collection. There is also a deep reflection of publicizing materials that were meant to be private and intimate. In particular, how the wartime censorship adds another layer of complexity to the nature of this correspondence. The curators’ own personal reflections communicated their own positionality towards the project and personal growth in a profound and touching way.

The project is built with open-source tools. The content management tool, CollectionBuilder is a set of static web templates for online collections created and maintained by librarians at the University of Idaho. The transcriptions are prepared with Oral History as Data, also a static web tool based on Github Pages and Jekyll to analyze and visualize transcripts, also by the same group at the University of Idaho.

I love the collection not only in the sense it teaches me about a dark episode in history effectively but also demonstrates how such a project can help each of us grow by reflecting on our own positions in relation to the history documented in the project.

Yi Shan is East Asian Studies Librarian at the University of Texas Libraries.

Further reading

- UT Libraries Asian Americans Studies Guide.

- Fonds RBSC-ARC-1786 – Joan Gillis fonds at UBC Rare Books and Special Collections, UBC Library. https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/joan-gillis-fonds

- Matthew McRae, “Japanese Canadian internment and the struggle for redress,” Canadian Museum for Human Rights. https://tinyurl.com/2xzujnhr?t=1687387156.

- Maryka Omatsu. Bittersweet Passage: Redress and the Japanese Canadian Experience. Toronto : Between The Lines, 1992.

- Mona Oikawa. Cartographies of Violence: Japanese Canadian Women, Memory, and the Subjects of the Internment. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.