Happy Open Education Week! We’re back today to share a few open educational resources (OER) chosen by members of the OER Outreach Working Group. Each of the resources below are great examples of OER in use at UT (and authored by our faculty and staff in several cases!).

OER are teaching and learning objects that are generally free of cost, but just as importantly, they are free of the legal barriers that often prevent their unrestricted reuse and adaptation. Each of these resources can be accessed and shared freely, but anyone can also make copies with changes that suit the needs of their class or personal study. For example, you could translate them into Spanish, change examples or images to enhance their relevance, or combine them with other openly licensed resources to create something entirely new! These are the permissions and power that open licenses confer to you.

Check these out, get inspired, and contact Ashley Morrison, the Tocker Open Education Librarian, if you’d like to know more or get help locating OER for your discipline.

Information Literacy Toolkit, reviewed by Sarah Brandt, Librarian for First-Year Programs

Authored by UT Libraries Staff & UT Faculty

Licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Information Literacy Toolkit is a set of customizable research and information literacy assignments, lesson plans, assessment tools, and course examples built over many years by UT Libraries staff and UT faculty. Though largely created with undergraduate classes in mind, these resources can be adapted for graduate-level courses. Most of the items in the toolkit are available as Google Docs so that they are easy to copy or download and modify for a particular course. This toolkit is a dynamic resource. Library staff add and update resources regularly, and work with faculty to add interesting course examples. UT faculty who want to implement an assignment from the Information Literacy Toolkit can request assistance from a UT librarian as they modify assignments for their purposes. We encourage instructors to take a look at this resource as they are creating research assignments and to send in feedback about resources they use or feel are missing from the toolkit.

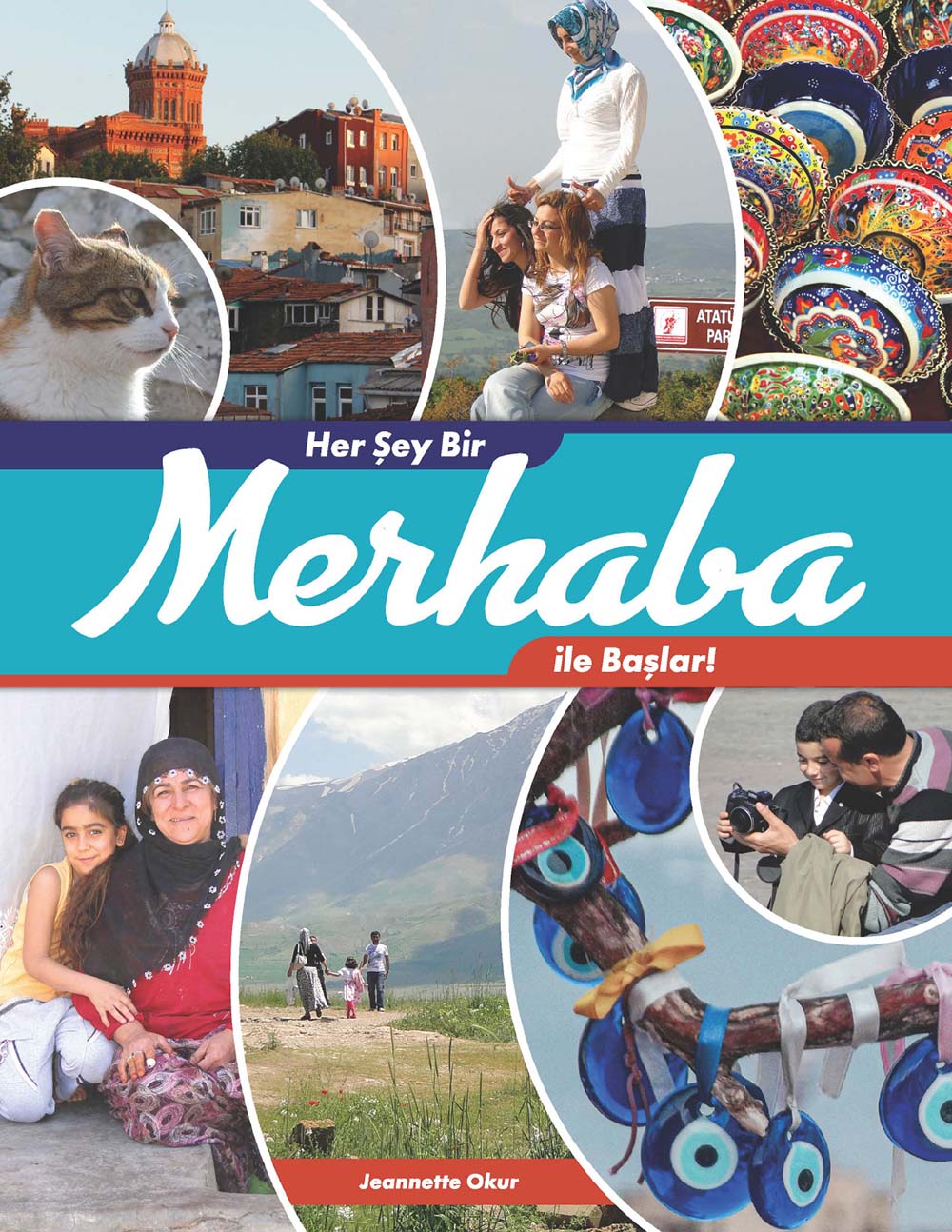

Her Şey Bir Merhaba ile Başlar! (Everything Begins with a Hello!), reviewed by Sarah Sweeney, Project Coordinator at COERLL

Authored by Dr. Jeannette Okur, University of Texas at Austin

Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Her Şey Bir Merhaba ile Başlar is an open textbook for intermediate Turkish language learners, the result of a collaboration between the author Jeannette Okur, native speakers, students, and COERLL. These four units address aspects of modern Turkish society: family, love and marriage, the environment, and art and politics. The content includes a variety of authentic texts, videos, audio, and images curated from the internet, as well as audio and video created specifically for this project. The textbook is available for free as a PDF or in Google Docs, where teachers and students can adapt it according to their individual needs. A print copy can also be purchased. Supplementary materials include Quizlet vocabulary lists and interactive Canvas exercises.

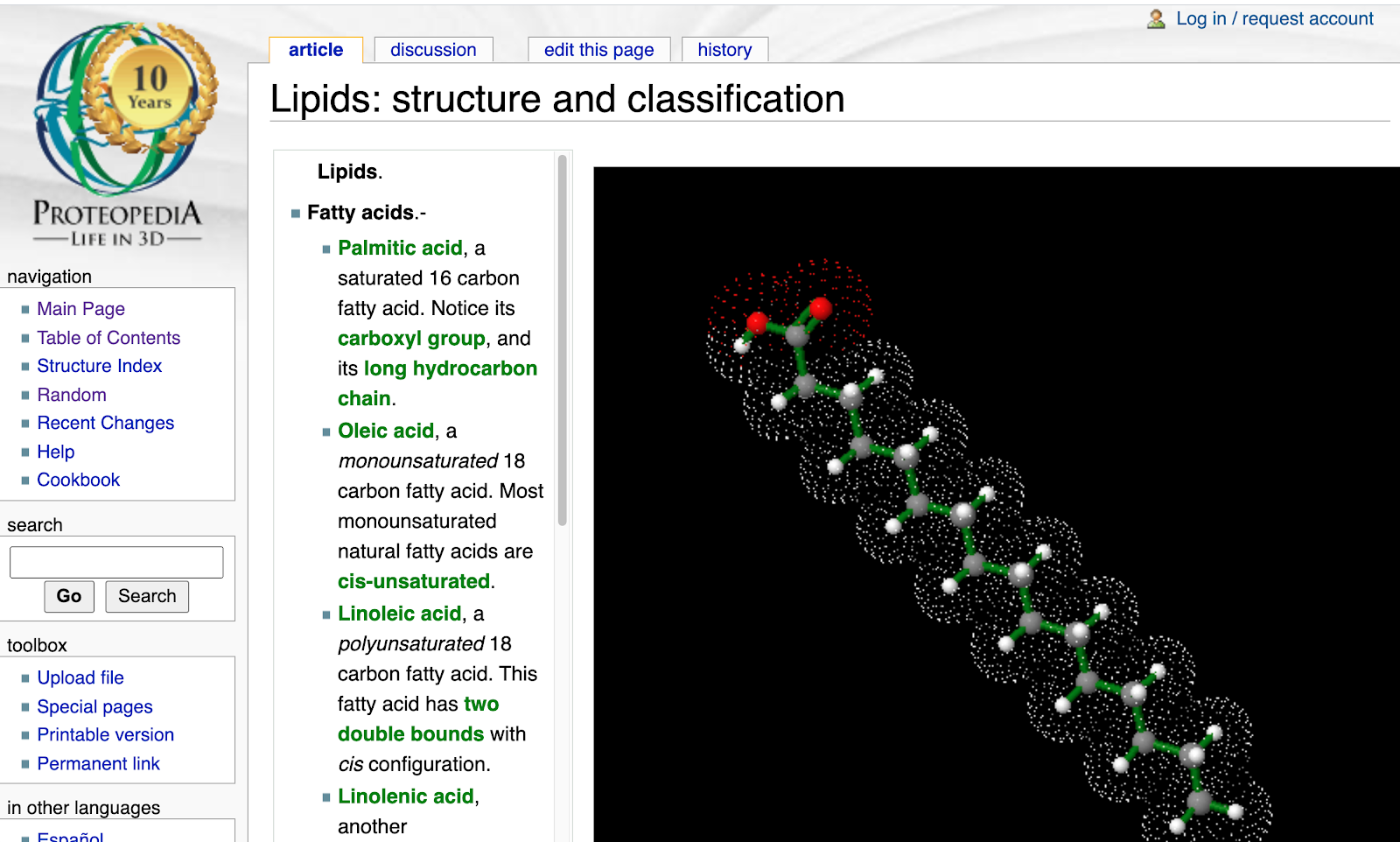

Proteopedia, reviewed by Hannah Chapman Tripp, Biosciences Librarian

Authored collaboratively

Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Image: Porto, A., Martz, E., Sussman, J. L., & Theis, K. (n.d.). Lipids: Structure and classification. Proteopedia – Life in 3D. Retrieved February 24, 2021, from https://proteopedia.org/wiki/index.php/Lipids:_structure_and_classification

Proteopedia is an encyclopedia containing protein, nucleic acid and other biomolecular structures represented in 3D rotating format using Jmol technology. The tool contains both annotated and unannotated structures, representing efforts by the biomolecular community worldwide and automatic weekly imports from the Protein Data Bank respectively. The resource also contains syllabi, quizzes, concept pages and more developed by educators with the intent of reuse in mind. Proteopedia can be edited by registered users, allowing the community to contribute to resource construction. Each page that is supplemented contains a contributors and editors section at the bottom with links to author profiles including academic credentials allowing for appropriate citation, responsibility for content and trust in the content.