Vea abajo para versión en español / Veja em baixo para versão em português

In honor of World Digital Preservation Day, members of the University of Texas Libraries’ Digital Preservation team have written a series of blog posts to highlight preservation activities at UT Austin, and to explain why the stakes are so high in our ever-changing digital and technological landscape. This post is part one in a series of five.

Introduction to Digital Preservation

BY DAVID BLISS, Digital Processing Archivist, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections; ASHLEY ADAIR, Head of Preservation and Digital Stewardship University of Texas Libraries

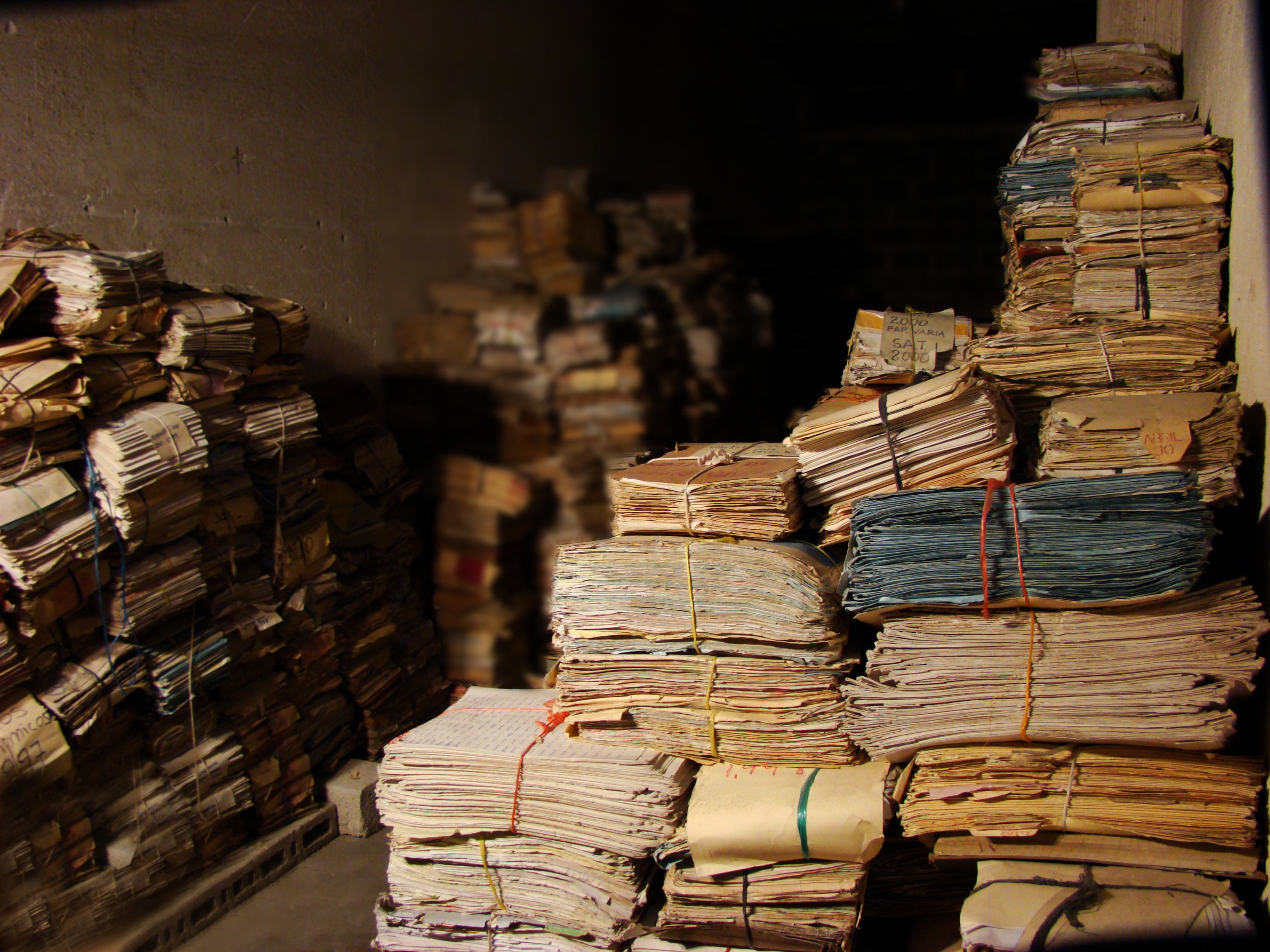

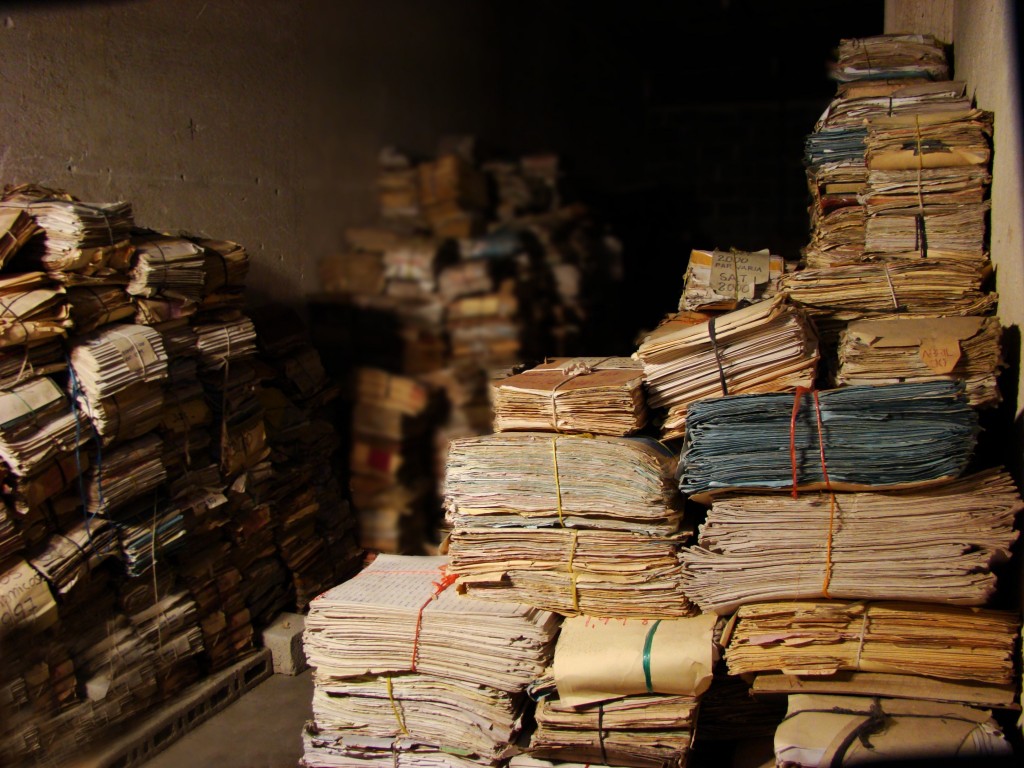

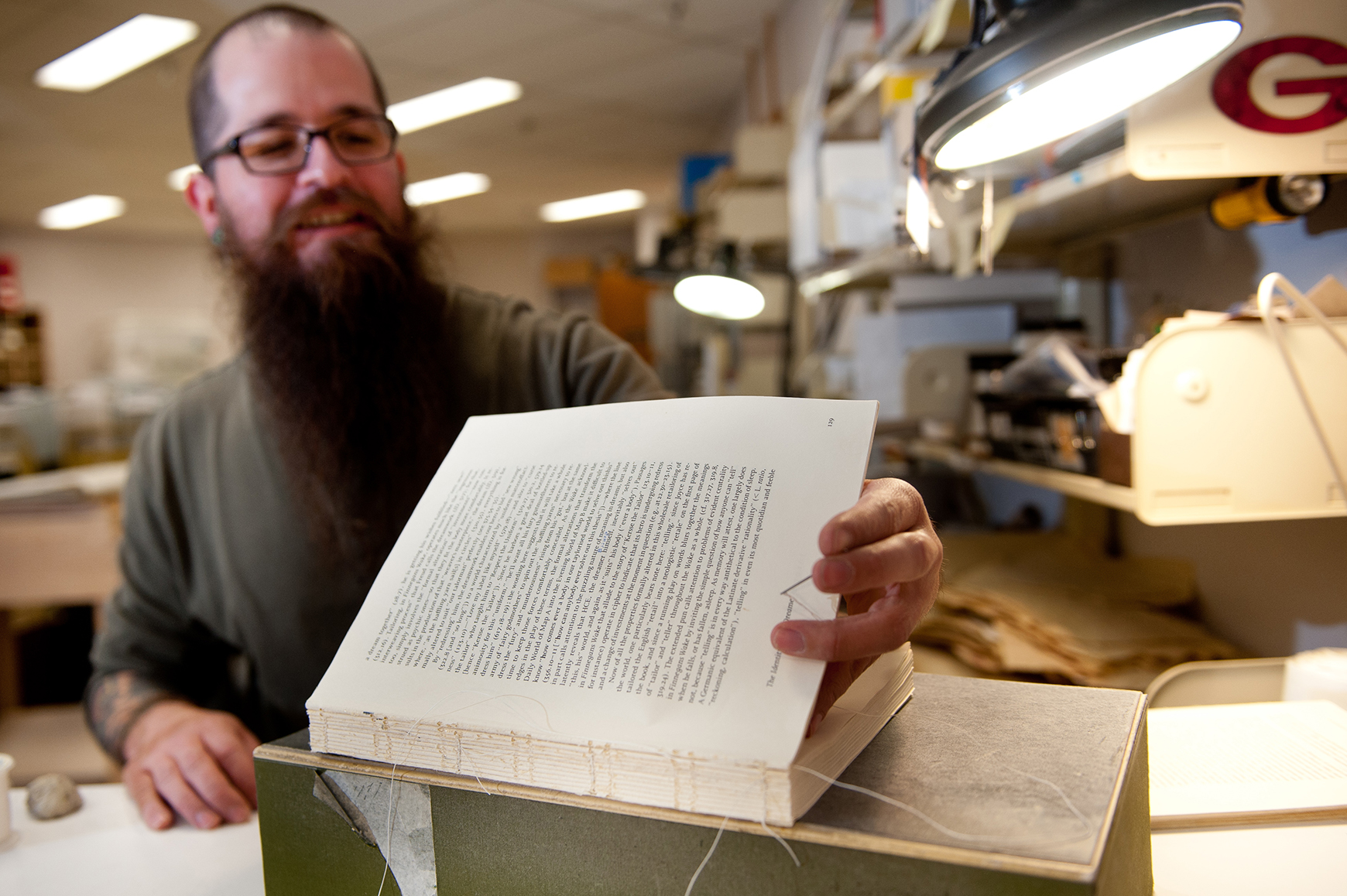

In recent decades, the archival field has been transformed by the rise of digital historical records. As computers of all kinds have worked their way into many areas of our professional and personal lives, collections of documents donated to archives in order to preserve individual and institutional histories have come to comprise both traditional paper records and those created using these computers. Digital records can be scans of paper or other objects, born-digital files comparable to paper records, such as Word or text documents, or entirely new kinds of objects, such as video games. Archivists are committed to preserving digital records, just like physical ones, for future generations to use and study. Digital preservation refers to the full range of work involved in ensuring digital files remain accessible and readable in the face of changing hardware and software.

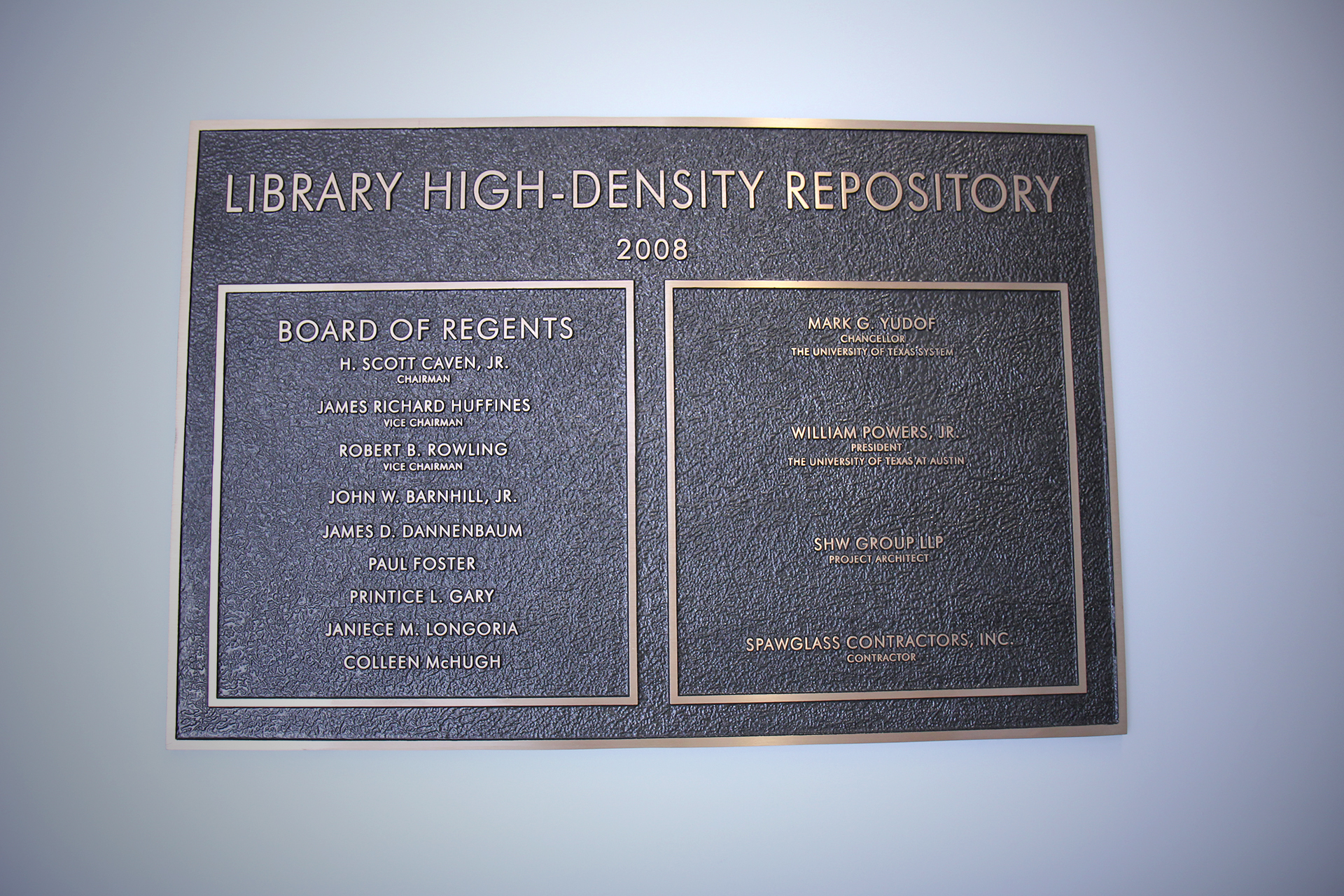

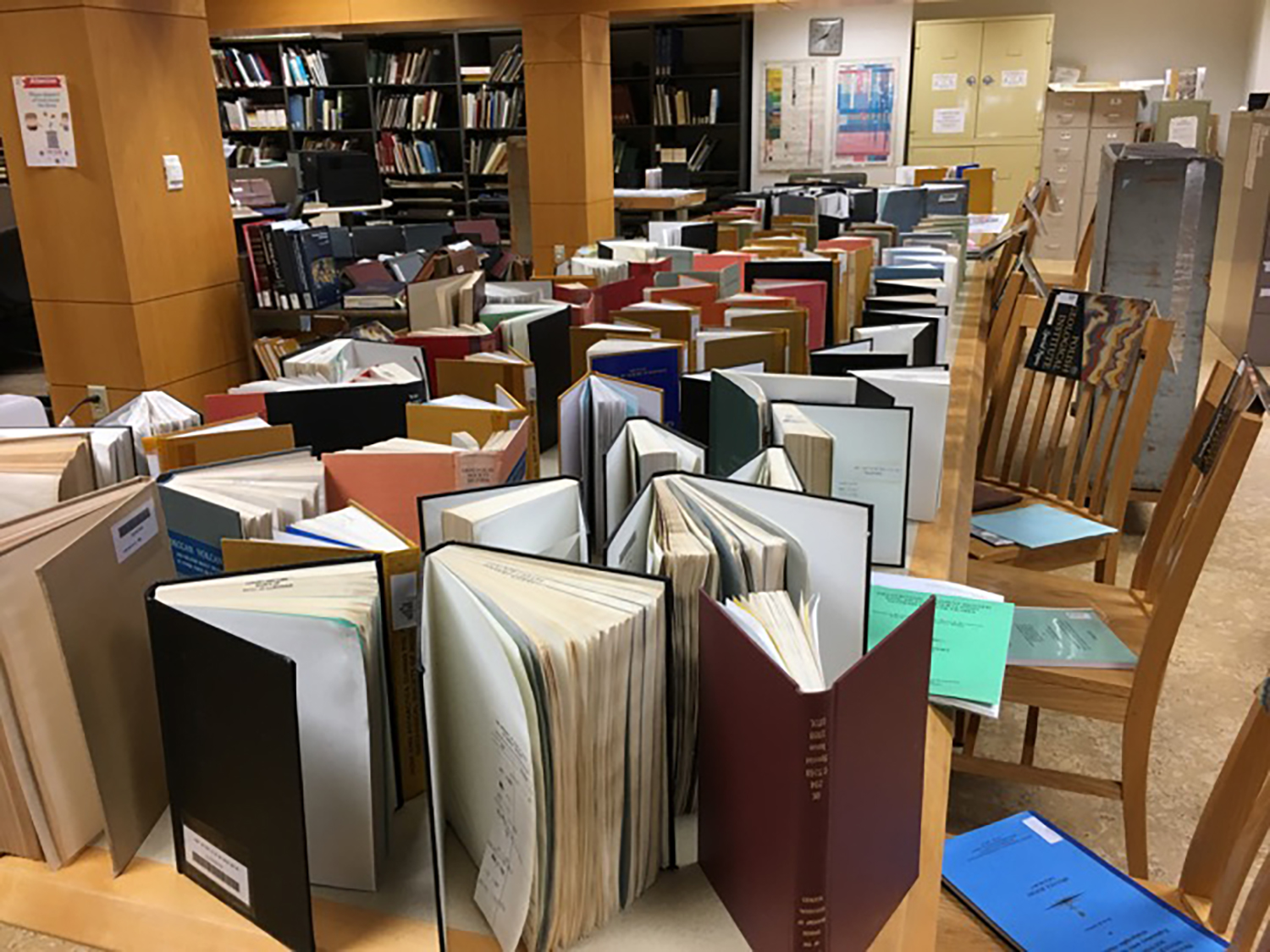

Unlike traditional physical media like paper, which can typically be kept readable for decades or centuries with proper housing and ambient conditions, digital files can be lost without periodic, active intervention on the part of archivists: legacy file formats can become unreadable on modern computers; hard drives and optical media can break or degrade over time; and power outages can cause network storage to fail. Digital archivists take steps to prevent and prepare for these contingencies.

There is no one perfect or even correct solution to the challenge of preserving digital files, so each institution may use different tools, standards, and hardware to carry out the work. Typically, however, digital preservation involves choosing suitable file formats, maintaining storage media and infrastructure, and organizing and describing digital objects in a standardized way that ensures future archivists and users can understand and access what has been preserved.

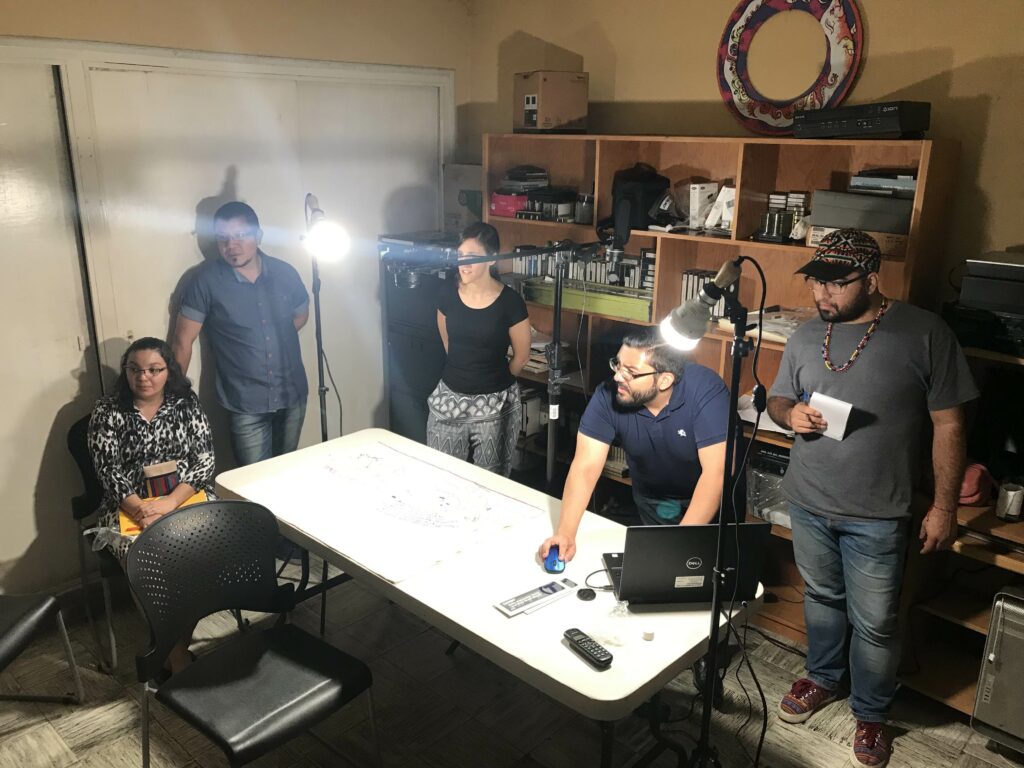

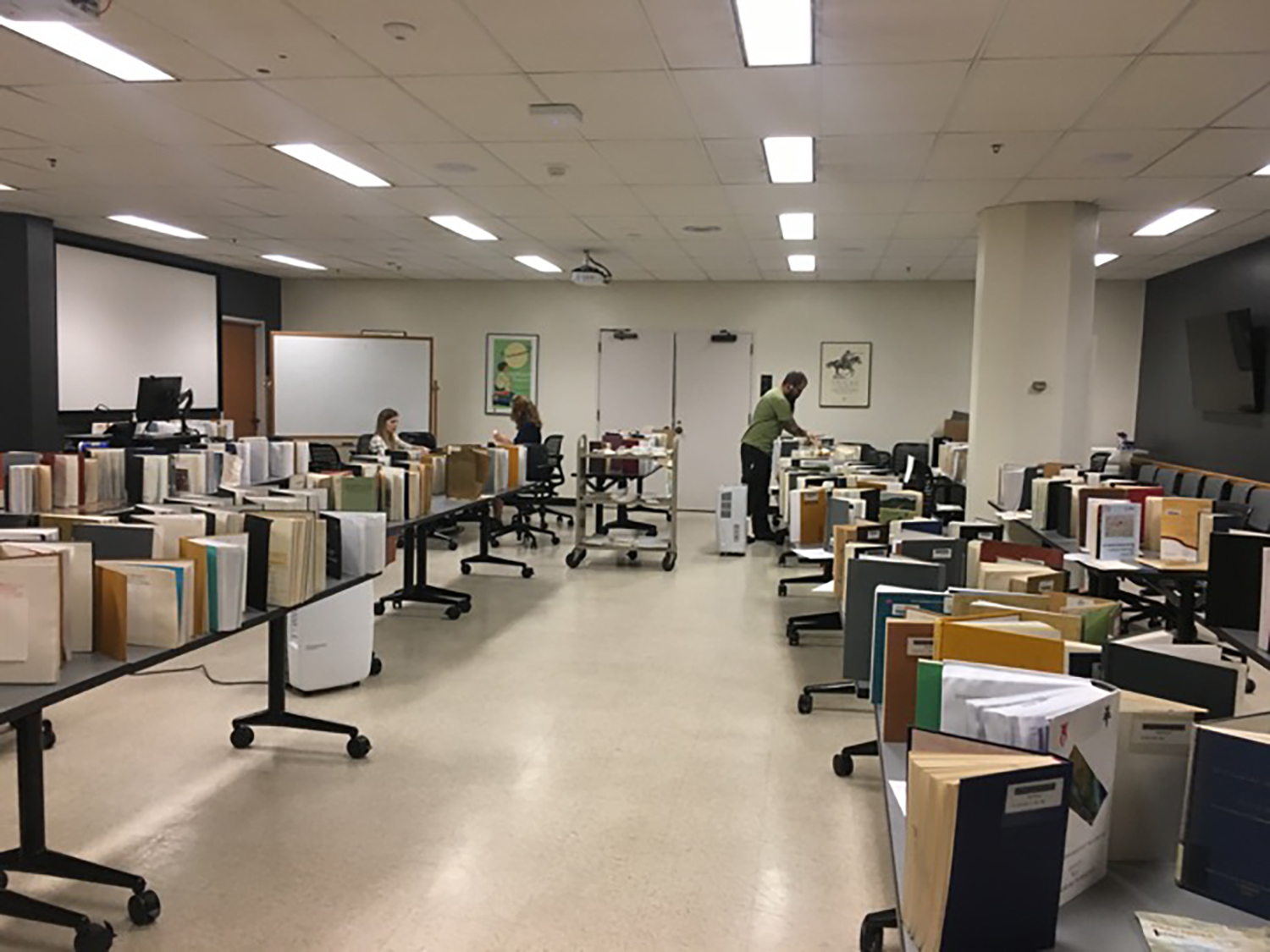

Digital preservation represents a significant effort that cannot be carried out by a single person or group. At the University of Texas Libraries, dissemination of digital preservation knowledge and skills is a crucial part of digital preservation practice. Training and pedagogy spread digital preservation expertise within the organization and out to researchers and partners, allowing the Libraries to preserve an ever-growing amount of valuable data.

Introducción a la preservación digital

Para el Día Mundial de la Preservación Digital, los miembros del equipo de Preservación Digital de las Bibliotecas de la Universidad de Texas han escrito una serie de entradas de blog que hacen destacar las actividades de preservación en la universidad, y para enfatizar la importancia de la preservación en un presente de cambio tecnológico constante. Este texto es el primero en una serie de cinco.

Traducido por Jennifer Isasi, Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation in Latin American and Latina/o Studies

En décadas recientes, el ámbito de los archivo se ha visto transformado con el aumento de los registros históricos digitales. A medida que las computadoras de todo tipo han pasado a formar parte de muchas áreas de nuestra vida profesional y personal, las colecciones de documentos donados a los archivos para preservar historias individuales e institucionales ahora presentan tanto los registros en papel tradicionales como los creados con computadoras. Los registros digitales pueden ser copias escaneadas de papel u otros objetos, archivos digitales nativos similares a los registros en papel, como documentos de Word o texto, o tipos de objetos completamente nuevos, como los videojuegos. Los archivistas están comprometidos a preservar los registros digitales, al igual que los físicos, para que las generaciones futuras los utilicen y estudien. Así, la preservación digital se refiere a la gama completa de trabajo involucrado en garantizar que los archivos digitales permanezcan accesibles y legibles ante el cambio de hardware y software.

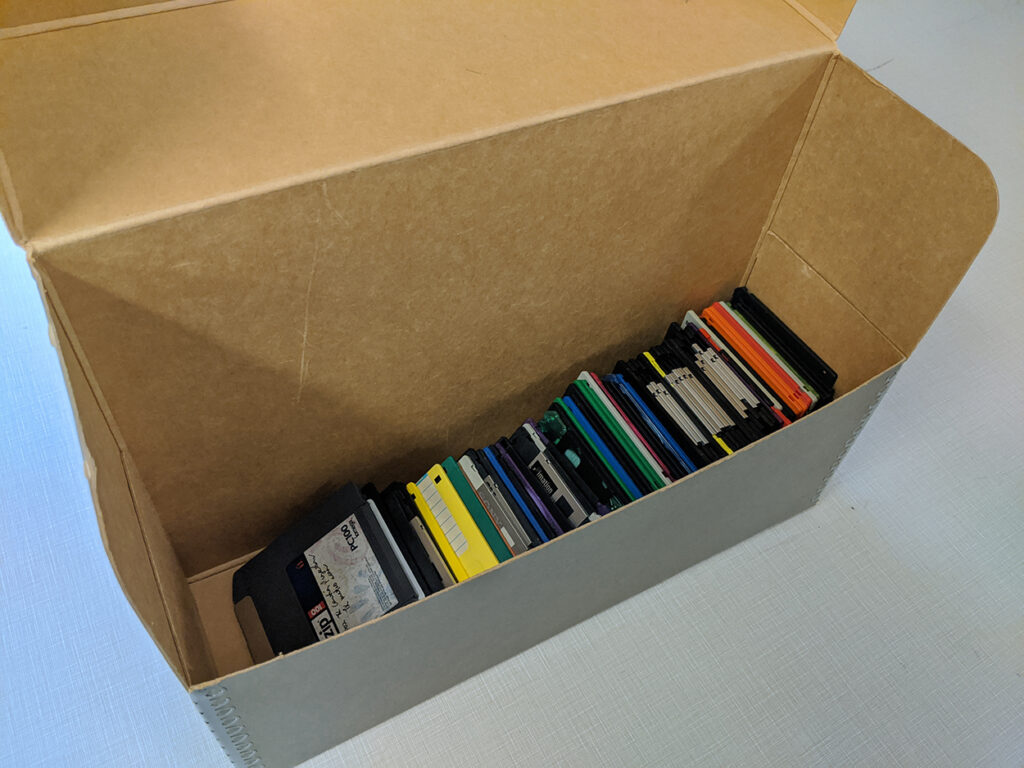

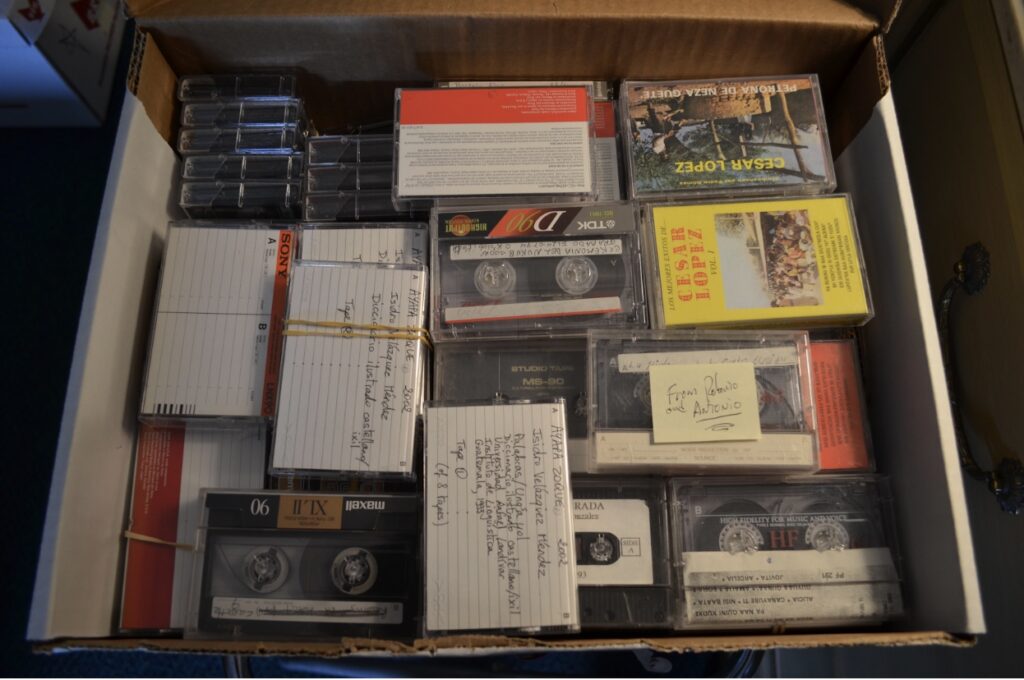

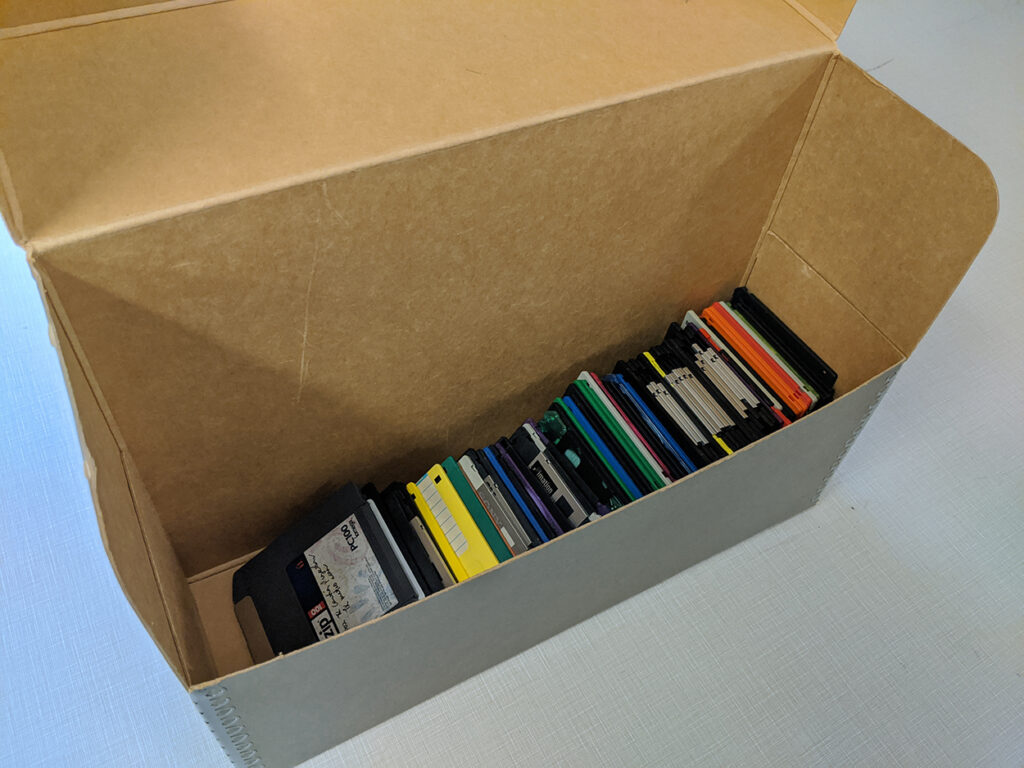

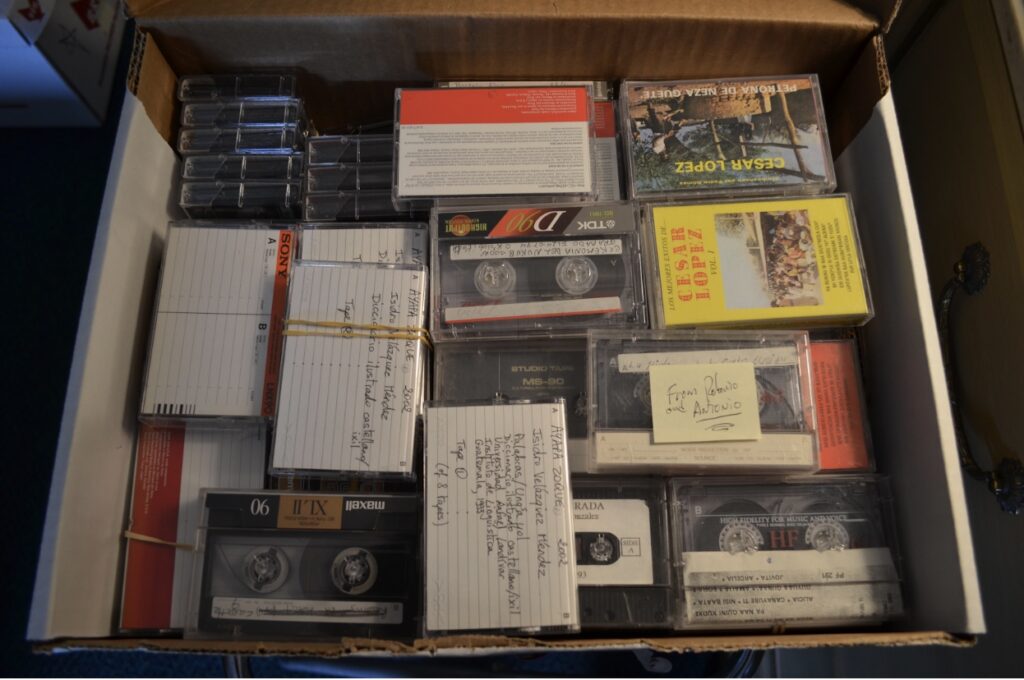

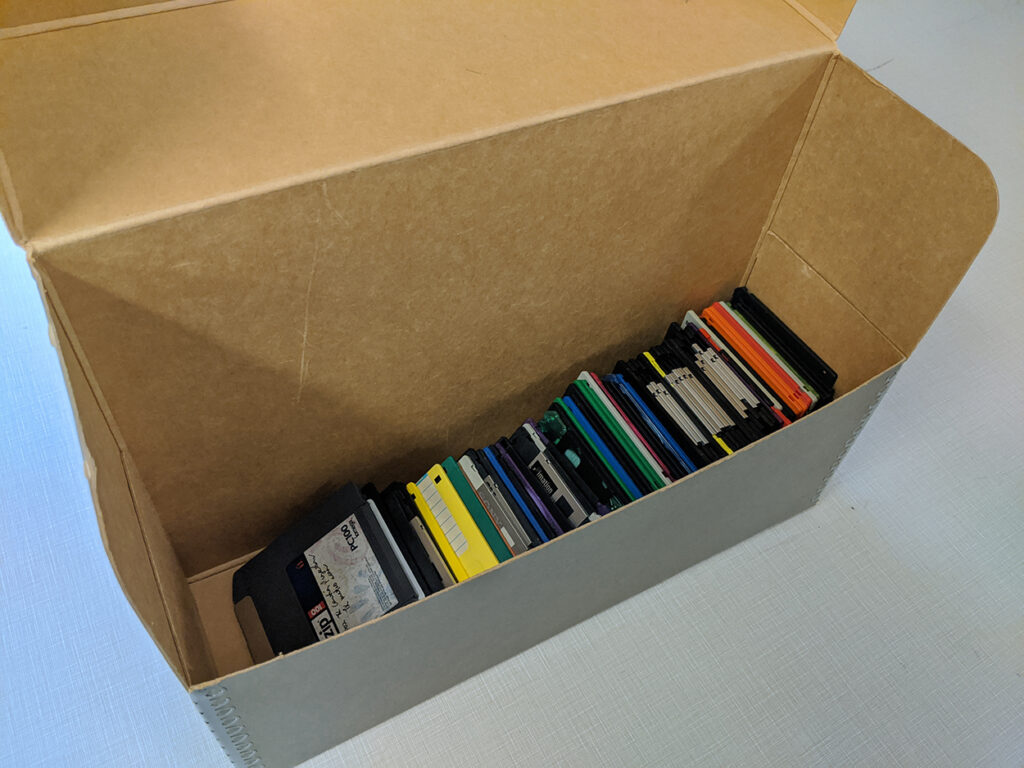

Una caja de disquetes, parte de una colección de archivos de las bibliotecas de la Universidad de Texas

A diferencia de los medios físicos tradicionales como el papel, que por lo general pueden ser preservados por décadas o siglos en condiciones de guardado adecuadas, los archivos digitales pueden perderse sin la intervención periódica y activa por parte de los archivistas: las computadoras modernas no pueden leer algunos de los formatos de archivo más antiguos, los discos duros o los medios ópticos se pueden romper o degradar con el tiempo y los cortes de luz pueden causar fallos en el almacenamiento en la red. Los archivistas digitales toman medidas para prevenir o prepararse para este tipo de imprevistos.

No hay una solución perfecta ni correcta para el desafío de preservar archivos digitales, por lo que cada institución puede utilizar diferentes herramientas, estándares y equipos para este trabajo. Por lo general, no obstante, la preservación digital implica elegir formatos de archivo adecuados, mantener medios de almacenaje y su infraestructura así como asegurar la organización y la descripción de los objetos digitales de una manera estandarizada que garantice que los futuros archivistas y usuarios puedan comprender y acceder al material preservado.

El trabajo y esfuerzo necesarios para la preservación digital no puede ser realizado por una sola persona o grupo. En el conjunto de bibliotecas de la Universidad de Texas, la difusión del conocimiento sobre preservación digital es una parte crucial de la práctica de preservación. Mediante esfuerzos de capacitación y pedagógicos tanto dentro de la organización como entre investigadores y colaboradores, estas bibliotecas están logrando preservar una cantidad cada vez mayor de datos relevantes.

Introdução à preservação digital

Traduzido por Tereza Braga

Para o Dia Mundial da Preservação Digital, os membros do equipe de Preservação Digital das Bibliotecas da Universidade de Texas escreveram uma serie de entradas de blog que enfatizam as atividades de preservação na nossa universidad, para explicar a importancia da preservação no contexto de um presente de tecnología em fluxo constante. Este texto é o primeiro numa série de cinco.

O advento dos registros históricos digitais causou uma completa transformação do setor arquivístico nas últimas décadas. Computadores de todos os tipos estão cada vez mais presentes em cada vez mais aspectos da vida profissional e pessoal. Essa mudança também afeta as coleções de documentos que são doadas a instituições arquivísticas com o intuito de preservar histórias individuais e institucionais. Hoje em dia, uma coleção pode reunir tanto registros tradicionais em papel quanto registros criados por esses diversos computadores. O que chamamos de registro digital pode ser uma simples página ou objeto que tenha sido escaneado ou qualquer arquivo que já tenha nascido em forma digital e que seja comparável com um registro em papel como, por exemplo, um texto regidido em Word. Registro digital pode também significar uma coisa inteiramente nova como um videogame, por exemplo. Arquivistas são profissionais que se dedicam a preservar registros digitais para utilização e estudo por futuras gerações, como já é feito com os registros físicos. A preservação digital pode incluir uma ampla variedade de tarefas, todas com o objetivo comum de fazer com que um arquivo digital se mantenha acessível e legível mesmo com as frequentes mudanças na área de hardware e software.

Uma caixa de disquetes, parte de uma coleção de arquivos mantida pelas bibliotecas da Universidade de Texas

Um arquivo digital é diferente do arquivo em papel ou outros meios físicos tradicionais, que geralmente pode ser mantido legível por muitas décadas ou mesmo séculos, se armazenado em invólucro adequado e sob as devidas condições ambientais. Um arquivo digital pode se perder para sempre se não houver uma intervenção periódica e ativa por parte de um arquivista. Certos arquivos em formatos mais antigos podem se tornar ilegíveis em computadores modernos. Discos rígidos e mídia ótica podem quebrar ou estragar com o tempo. Cortes de energia podem causar panes em sistemas de armazenagem em rede. O arquivista digital é o profissional que sabe tomar medidas tanto de prevenção quanto de preparação para essas e outras contingências.

Não existe solução perfeita, ou sequer correta, para o desafio que é preservar um arquivo digital. Diferentes instituições utilizam diferentes ferramentas, normas e hardware. De maneira geral, no entanto, as seguintes tarefas devem ser realizadas: escolher o formato de arquivo adequado; providenciar e manter uma mídia e infra-estrutura de armazenagem; e organizar e descrever os objetos digitais de uma maneira que seja padronizada e que permita a futuros arquivistas e usuários entender e acessar o que foi preservado.

A preservação digital é um empreendimento importante que não pode ser executado por apenas um indivíduo ou grupo. Na UT Libraries, a disseminação de conhecimentos e competências de preservação digital é uma parte essencial dessa prática. Temos cursos de capacitação e pedagogia para disseminar essa especialização em preservação digital para toda a organização e também para pesquisadores e parceiros externos. É esse trabalho que capacita a Libraries a preservar um grande volume de dados valiosos que não pára de crescer.