By Albert. A. Palacios, PhD

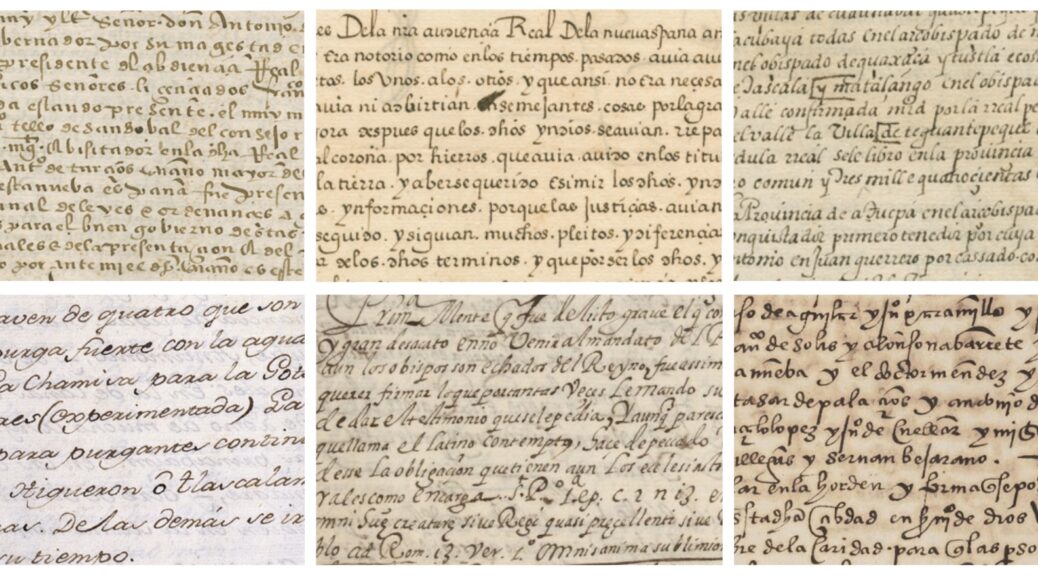

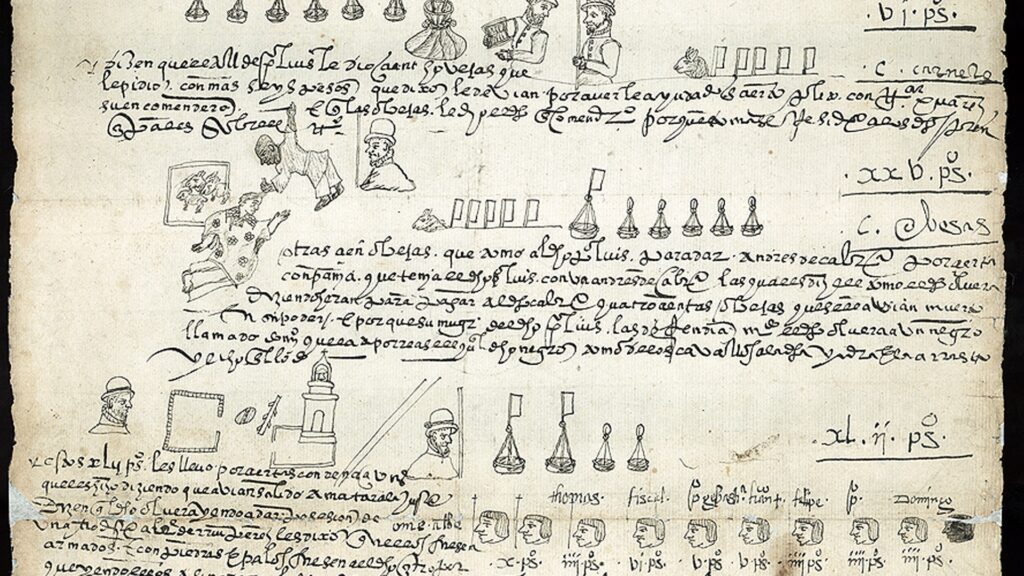

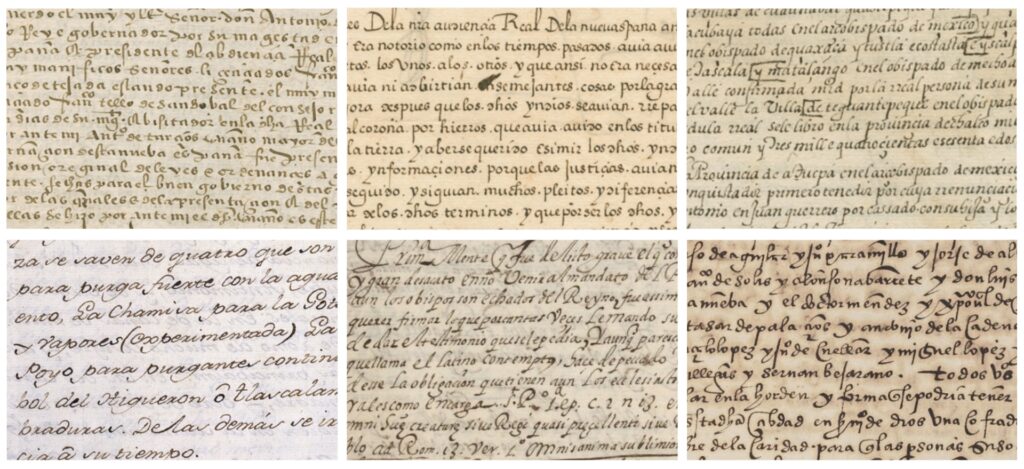

It is no secret that the Benson Latin American Collection preserves one of the most important Spanish colonial archives in the United States. Within the pages of hundreds of volumes and archival boxes in its stacks are countless historical gems documenting the lived experience of colonized people, colonizers, and everyone in between. However, these perspectives are largely inaccessible: archaic penmanship and obscure writing conventions encode these histories on brittle paper.

For years, the LLILAS Benson Digital Scholarship Office has been experimenting with digital technologies to transform this “unreadable” Spanish colonial archive into accessible humanities data for scholars. However, we tried something new this past year and reversed the equation: We convened colonial Latin Americanists online to transform handwritten words on pages into digital text that they could then use to make the digital humanities (DH) more accessible. This resulted in the “Spanish Paleography and Digital Humanities Institute,” a free online program that provided scholars with practical training in the reading and visualization of 16th- to 18th-century manuscripts in Spanish. The program’s syllabus and logistics were designed by Abisai Pérez Zamarripa, LLILAS Benson Digital Scholarship graduate research assistant and doctoral candidate in history, and myself. Anyone with advanced Spanish-reading proficiency was invited to apply.

“I found this institute thoughtful, generative, and inspiring. The coordinators made every effort to show the participants relevant tools and encourage our progress. It was uniquely helpful to identify DH methods and tools that would make sense in an early modern context and to discuss questions that relate to our field.” — Fall 2021 participant

Colonial Latin Americanists from all over the world applied. While we were only planning to lead one institute, the overwhelming response to our call for applications prompted us to offer two, one in the fall (November–December 2021) and another in the spring (January–March 2022). In all, we accepted 60 participants, including 35 graduate students, eight junior faculty, eight tenured professors, five archive and library professionals, and four independent researchers. By the end of the academic year, we had trained scholars in 11 countries and 18 U.S. states who had varying experience in Spanish paleography and the digital humanities.

“The facilitators were very supportive, and the workshop itself was an invaluable opportunity to meet scholars from across the U.S. and Latin America despite not being able to travel, and to experience a variety of digital humanities tools relevant to our work.” — Dr. Mallory E. Matsumoto, Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

One of our main objectives was to help participants obtain and hone Spanish paleography skills. We invited experts from Germany, Portugal, France, and Mexico to provide introductions on specific colonial institutions and their records to expose students to specialized writing conventions and abbreviations. Each Friday, we would break the cohort into groups so that they could collaboratively read and transcribe the week’s case study in a shared Google Doc, which enabled us to give them live feedback and corrections on their transcriptions.

“The group transcription sessions every Friday were invaluable as they allowed us to decipher and discuss doubts with colleagues throughout the [transcription] process, while learning from those with greater knowledge.” — Spring 2022 participant

The spirit of collegiality during these sessions was truly inspiring. We witnessed how scholars, especially those with advanced Spanish paleography skills, actively supported each other in deciphering the texts. After the institute ended, some commented that they considered this group work as “one of the most enriching experiences from the institute.”

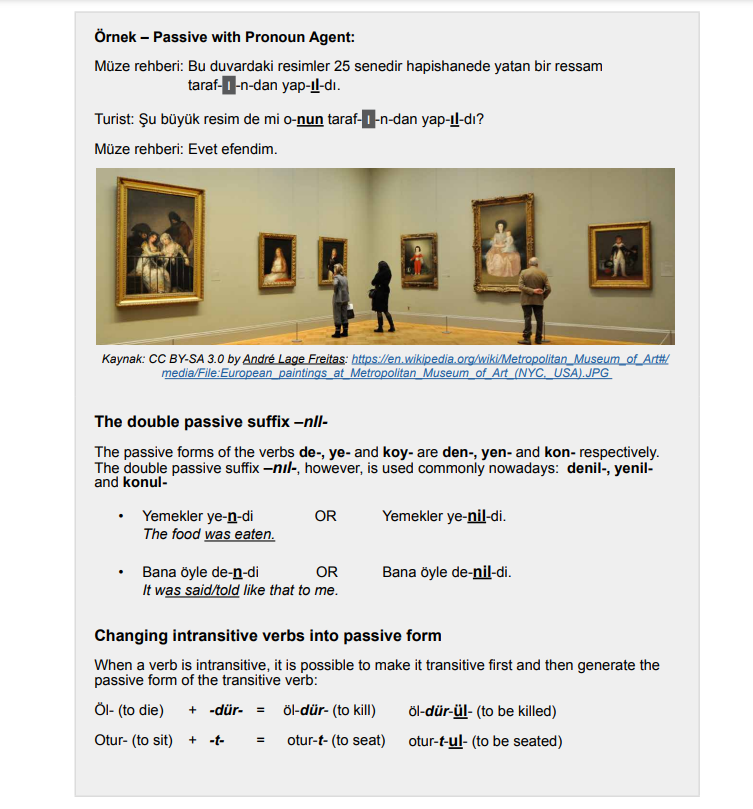

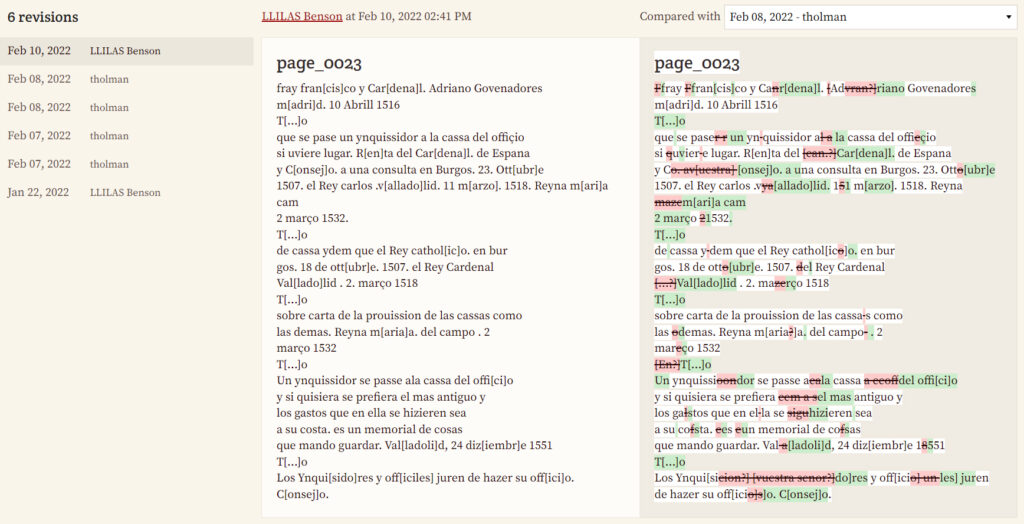

After the collaborative transcription sessions, participants continued to hone their paleography skills through assigned weekly homework. Each scholar transcribed two to four pages in various handwriting styles using the University of Texas Libraries’ instance of FromThePage, a platform that enables collaborative transcription work and version tracking. Once they were done with a page, Abisai and I reviewed and corrected the transcriptions, which FromThePage documented and showed, as seen above, to further the students’ understanding of the scripts and abbreviations.

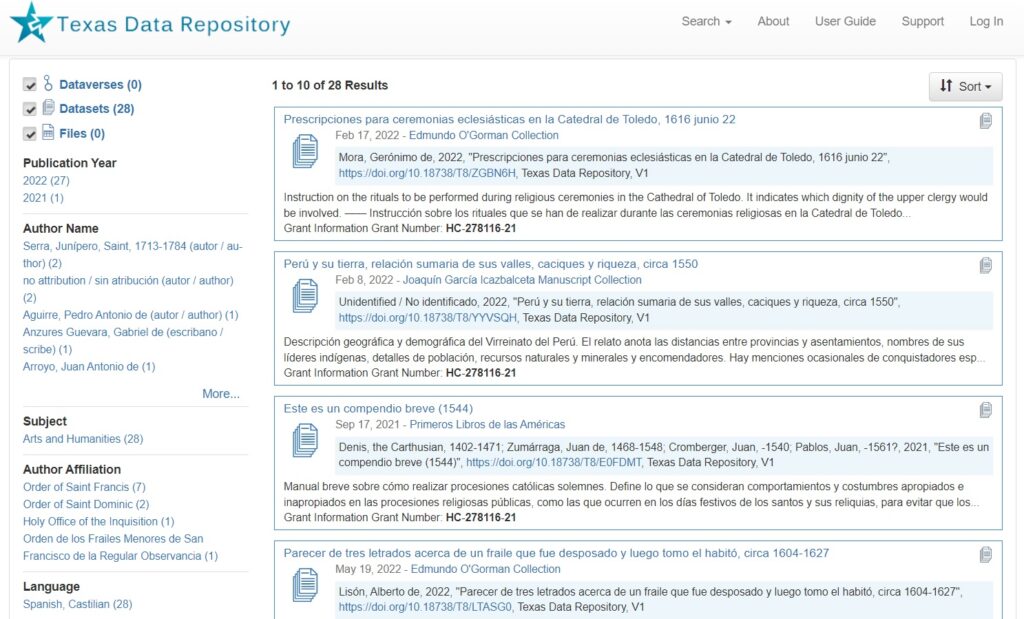

Besides learning how to read the archaic penmanship, scholars were simultaneously helping us enhance the accessibility of the Spanish colonial collection. One the one hand, the cohorts transcribed, and consequently made intellectually accessible, over 90 documents (1,000+ pages) preserved in the Benson Latin American Collection. We are currently publishing them in the Texas Data Repository and will soon ingest them in the University of Texas Libraries’ Collections portal with the images of the original materials to broaden access.

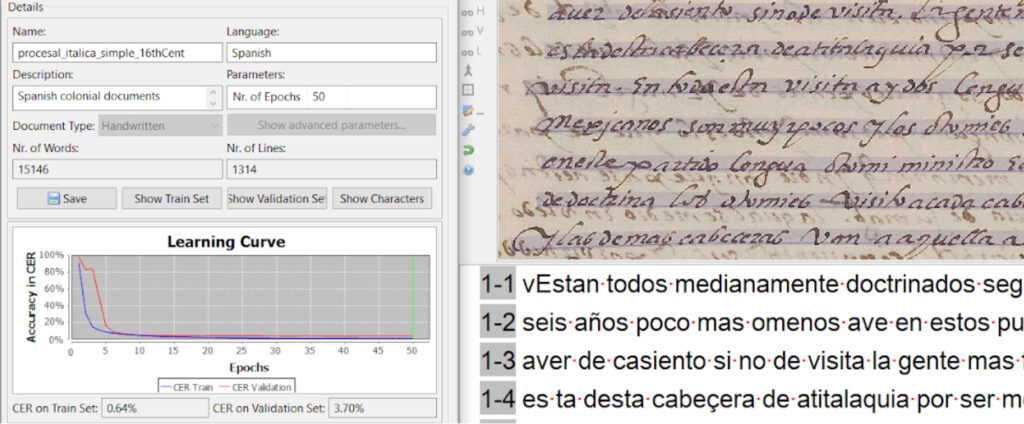

On the other hand, participants also helped us leverage machine-learning technologies to automate this work in the future. As part of the “Unlocking the Colonial Archive” NEH-AHRC grant project, we are reusing these transcriptions to train handwritten text recognition (HTR) models for each of the handwriting styles we commonly find in Spanish colonial documentation. We are then running these models on untranscribed materials at the Benson and in other digital archives to obtain usable automatic transcriptions. To see a list of participants who made a significant contribution to this effort, visit the project website.

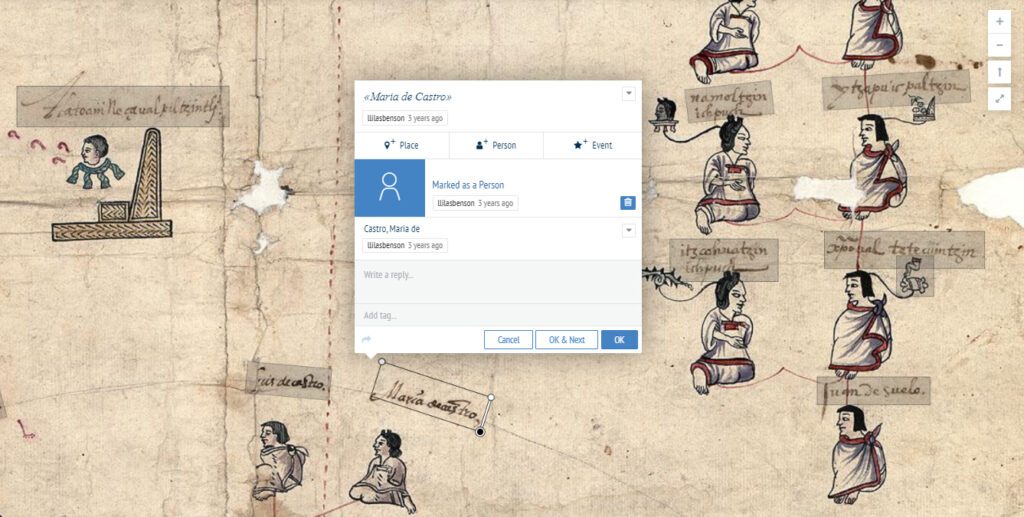

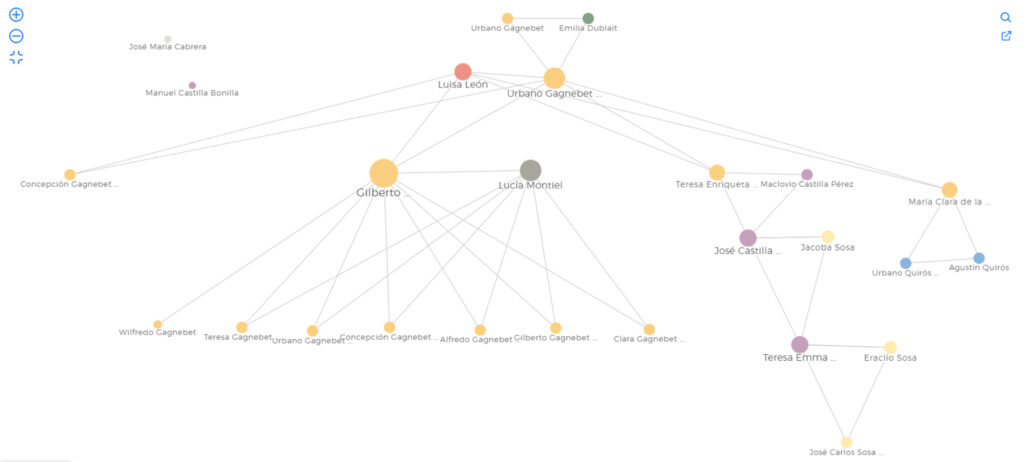

With transcriptions in hand, students then used them to learn several free and open-source digital humanities tools. Each Monday, we demonstrated how to extract, visualize, and analyze data from these transcribed texts in different platforms, including Recogito, Voyant-Tools, ArcGIS, and Onodo. As a capstone experience, we asked participants to develop and present a pilot digital humanities project using these tools and texts relevant to their research.

“I honestly did not know what to expect going into this institute. My focus was to improve my paleography skills with the digital programs as a benefit. Now, not only am I more confident in my paleography skills, but I have a plethora of digital tools to use for my projects.” — Spring 2022 participant

Given the positive reception and subsequent demand for such training, we will be leading another round of institutes this fall, August 15–September 30, 2022, and next spring, January 23–March 10, 2023. So if you are interested, check out the call for applications and join the collaborative “unlocking” of the Spanish colonial archive!

“I think it is a very complete and ambitious program. You taught me many tools that changed my way of doing history, of thinking about the social sciences and the humanities. I am very grateful to you. I hope you continue to be very successful and that this project continues to grow.” — Fall 2021 participant

These institutes would not have been possible without the support of these individuals:

- Dr. Manuel Bastias Saavedra, Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory and Adjunct Professor at the Institute of Latin American Studies, Freie Universität Berlin (Germany)

- Dr. Berenise Bravo Rubio, Researcher-Professor at the National School of Anthropology and History (Mexico)

- Brittany Centeno, Preservation Librarian, UT Libraries

- Dr. Guillaume Gaudin, Researcher-Professor at the University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès (France)

- Dr. Lidia Gómez García, Researcher-Professor at the Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla (Mexico)

- Ryan Lynch, Head of Special Collections, LLILAS Benson (United States of America)

- Dr. Kelly McDonough, Associate Professor at the Spanish and Portuguese Department, The University of Texas at Austin (United States of America)

- Dr. Patricia Murrieta-Flores, Professor in Digital Humanities and Co-Director of the Digital Humanities Centre at Lancaster University (United Kingdom)

- Dr. Javier Pereda, Senior Researcher at the Arts & Humanities Research Council and Senior Lecturer in Graphic Design and Illustration at Liverpool John Moores University (United Kingdom)

- Theresa Polk, Head of Digital Initiatives, LLILAS Benson (United States of America)

- Dr. Miguel Rodrigues Lourenço, Researcher at the Center of the Humanities, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Portugal)

- Susanna Sharpe, Communications Coordinator, LLILAS Benson (United States of America)

- Katherine Thornton, Digital Asset Delivery Coordinator, UT Libraries (United States of America)

- Krissi Trumeter, Financial Analyst, LLILAS Benson (United States of America)

This initiative was generously sponsored by:

- National Endowment for the Humanities (United States of America)

- Arts and Humanities Research Council (United Kingdom)

- LLILAS Excellence Fund for Technology and Development in Latin America

Albert A. Palacios, PhD, is the Digital Scholarship Coordinator at LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, The University of Texas at Austin.