Established in 2018, the University of Texas Libraries’ Diversity Residency Librarian program offers entry-level librarians from diverse backgrounds the opportunity to develop skills and professional growth while gaining practical experience in an academic library setting. The program is designed to align with the professional goals and interests of the residents as well as the strategic priorities of the Libraries. The program supports the goals of the Association of College & Research Libraries Diversity Alliance program.

This term’s incoming librarians – Jeremy Thompson and Karina Sanchez – began their residencies over the summer remotely, but are now immersed with their initial rotations with significant time spent onsite at the various library locations. We sat down with the pair to get some personal insights and to learn about their expectations for the program.

Tex Libris: Tell us a little bit about your backgrounds – where you’re from, where you studied, what your interests are and what it’s like since you’ve come to the Libraries.

Jeremy Thompson: Well, I call Arizona home, but I’m originally from Indiana. But I moved to Arizona when I was nine and went to the University of Arizona where I did my undergrad. I was a history major and Information Science & eSociety major. And I got my master’s there, too, in library and information science. I have multiple backgrounds in library work. I worked for six years at the Arizona State Museum. Then during that time I also took internships. So, I worked a year and a half of the 390th Memorial Museum, which was a World War II Museum dedicated to the bomber group. Then I worked for two years for UArizona’s special collections and then I did it and I was a junior fellow at the Library of Congress. And when I was graduating I was looking for all kinds of jobs, this position popped up and I told myself digital archives has always been an interest of mine and I just thought of something I could learn on the job somewhere. The original plan was to get a traditional kind job and then just build and becoming a digital archivist. But if I could get into this program and actually focus on digital archives, then that would be great for my career and something I actually wanted to do. I got this career and I’m mainly focusing on when digital archives and digital processing. That’s my main focus and why I’m here.

Karina Sanchez: I’m from Los Angeles, California, and I was born and raised in the valley there. For my undergrad, I went to UC-Irvine, which was like an hour away, and I majored in English and education. And during my undergraduate career, I went to a special collection workshop and that’s where I became interested in working in libraries and specifically special collections. And remember before that I thought, ‘I don’t want to be a librarian – they just sit at the desk, you know?’ But then after that I realized that there’s so much to librarianship and archives and special collections, and there’s so many jobs related to that. Once I graduated from Irvine, I earned a Getty Multicultural Undergraduate internship, but it was at Olvera Street (El Pueblo Historical Monument), which is a historical Mexican monument. From there I went to the Huntington Library, and working there has really informed what I want to do for work. After the Huntington, I got my library information Masters at UCLA, and I thought I wanted to stick with reference. Working there my supervisor, allowed me to critically analyze our space and how it impacts people of color and how it impacts people who just don’t have the privilege to use these spaces. I think that’s where my specific interest is – working with students of color, researchers of color, people who come from low income areas, because their perspective is so important and how research is perceived.

TL: So what made you decide to settle on the residency instead of going directly into a professional career? Was it a learning learning opportunity or was it an experiential opportunity that you saw there?

JT: It was both. I saw this as an opportunity to actually branch out and explore – with it being a three year program, I knew I would be able to take my time. I know that both of us are younger people in the field, so we had time to explore, and I knew I would get the experience that I needed and also be able to explore what I wanted to.

KS: I think I found out about the diversity resident librarianship before I found out that UT Austin had it, and because I had a job, I was not going to stress out too much about it. I needed to focus on graduating. I was just casually looking for stuff, and in January I saw that North Carolina was advertising for a diversity resident librarian. When the UT Austin position popped up, I read the description. There were other positions and I compared it to the other ones, but this one sounded perfect. It was very focused on learning and teaching. I didn’t feel like I needed to know all this stuff before I got in, so it didn’t feel as intimidating as some of the others. And I remember talking to my supervisor at the Huntington – she’s a mentor for me – and she said, “You should apply for this, you’ll learn more than just special collections – you’ll be better, you’ll be rounded out.” And it’s an academic library so it’s really great experience. With her help I applied and I’m happy I was able to get it.

TL: What are your expectations coming into the program?

KS: I guess my expectations coming in were very much about learning. I had to tell myself, ‘Don’t worry about going in there and feeling like you need to know everything because there’s just so much and this institution is so big.’ The first week of doing my informational interviews I realized that there are librarians for a lot of subject areas that I didn’t even consider. I realized quickly that it is okay to ask questions and learn. And I think that’s the mentality I’ve had – it’s an expectation to learn and to gain skills that I don’t have. Once I’m done with the program, hopefully it will be a bit easier to apply for the ideal librarian job.

JT: I came in wanting to be a digital archivist and that’s my expectation. I remember when I was interviewing for this position, I wanted to make sure it was worth my time because I am experienced. And while I was interviewing for here, I was also interviewing LSU for a manuscript processing possession, which I didn’t get – so (laughing) luckily I got this one. I just wanted to make sure that I that I came in expecting to come out a digital archivist, and making sure that I was going to learn something new. And so far I’ve learned a lot of things, and I’m only five months in.

TL: You both had previous experience in special archives. UT has a depth in special collections, so was there something about the special collections at the university that compelled you to apply here?

KS: Yeah, I remember when I was at UCLA, there’s a librarian there now, T-Kay Sangwand, and I remember seeing one of her presentations about a digitization process at the Benson (Latin American Collection) and the outreach the Libraries did in other countries, and I thought that was really cool. I remember seeing this position open and wondered if I might get the chance to work with the digital initiatives group or to work where T-Kay was working. And then when I reviewed our rotation options, I saw that digital initiative was part of the rotation, and it’s just perfect that it worked out somehow. I’m really excited to work with them and to understand more about the digital initiative outreach that they do. Also the Benson is Latinx-focused, so I’m really excited just to get that perspective because the Huntington was a very European-focused collection, while this collection has more diversity, even though there is still some intrinsic whiteness and colonization.

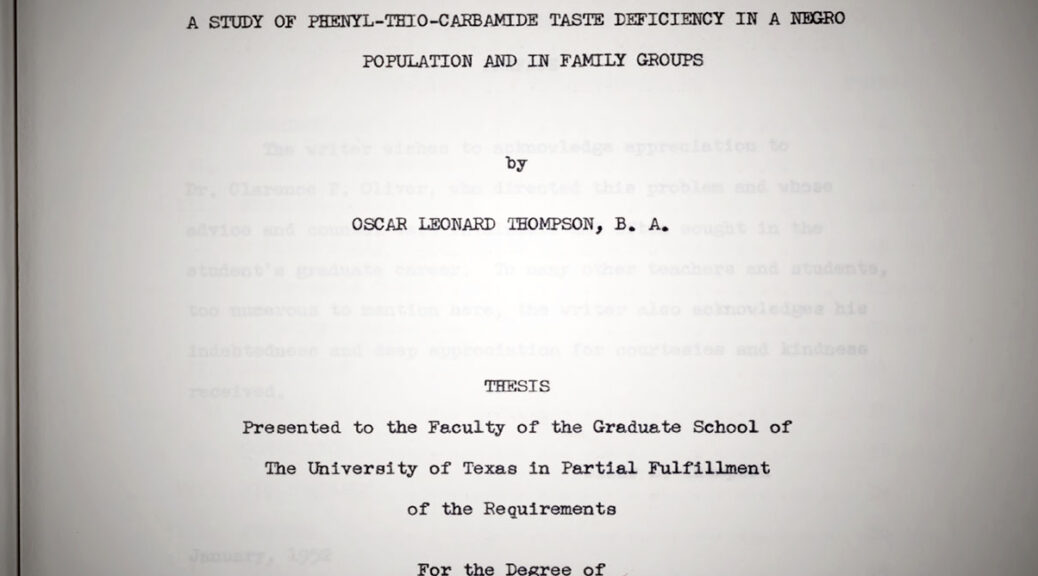

JT: Coming into it just finding the job posting, I was like, ‘Oh yeah…the University of Texas – that seems like a good place to work.’ Getting into the interview process and doing the research about the Libraries, one of the things I was impressed with is the Black Diaspora Archive (BDA), which I’ll be working on in my next rotation. Being in Arizona and working for their special collections and the Arizona State Museum, I’ve worked with Latinx collections and Native American collections, but I’ve never had the opportunity to work with a Black collection. And for my project at the Library of Congress, I was supposed to work on the African American Collection but it was right as the pandemic started, so they had to go virtual, so I worked in a different collection. Having the opportunity to actually work with a Black collection and learning in my interview from (Black Diaspora Archivist) Rachel Winston that the BDA is new and it doesn’t have a lot of digital components – just being able to be in on the ground floor for the collection and add in my own piece and my own work to the is to the archives something that I’m excited about.

TL: What are the what are the other areas of interests for you each here?

JT: Teaching services. One of the things that I’m impressed with again – going back to special collections – is Theresa Polk’s post-custodial, but also teaching what we’re doing. One of the things that I like about archives is the problems encountered and the solutions that come from those, but also having to not only find a solution but also adapt it so it doesn’t just stay with the institution. One of the things that we typically do when we find the solution is create a workflow so that we can inform others how we went about that process, and it can be reverse engineered. That’s one of the things that I enjoy and I plan on focusing on is teaching what we do so that outside communities can do the work, decentralizing the archival process.

TL: So if they are working on a post custodial project and you had the chance to go and do fieldwork with them where they’re teaching folks how to use technology in the field to digitally-preserve resources, would that be something you might jump at?

JT: Yeah, I’ve worked on a similar project in the past. In Tucson, there’s the Dunbar Pavilion school. The Dunbar was the first segregated school for African Americans in Tucson – they were having a reunion – and special collections were on hand with portable scanners to digitize photographs and put them on USB drives. And it wasn’t a requirement that they had to give us a copy, but we asked. It was a process to show people that you can do this yourself, you can preserve your own history. So, yeah, if there was an opportunity to go out in the field and actually do that work and produce onsite metadata, it is something that I would be interested in.

KS: Right now I’m working on an assessment with (Assessment Librarian) Maria Chiochios learning the assessment process and the survey process, and what to assess. There was a lot of assessment that we probably should’ve done at the Huntington, but we didn’t have the time or the staff. And going back to the Huntington, as with many museums and academic institutions, there are issues with how people use space. I’ve gotten to talk to (User Experience Designer) Melody Ethley about the user experience process and how people use space, how it impacts the research – especially if you’re a person of color. I am interested in understanding how people of color use special collections, since these spaces are not built for them and many haven’t encountered these resources can be a whole new world thus being scary. Also, at the Huntington, we didn’t have a lot of outreach. I think one of the rotations I’ll be doing is with Teaching and Learning, and I’m excited to work with undergrad students because I never had that chance before. I’ve always worked with professors and PhD students, who already knew exactly what they were doing. I’m excited to work with undergrads who are still trying to figure out what they’re doing and exploring the space. At the Huntington to I was able to develop a virtual reading room during the pandemic, which is basically a service where researchers – whether they’re local or out of the country – able to see our materials virtually through a document camera. In doing that, I realized how important the technology and the digital aspect of special collections are. I’m excited to work with (Benson Digital Scholarship Coordinator) Albert Palacios because he does the Latin American Digital Initiatives, but he also does the outreach and public facing work. I feel like it’s something I don’t know much about and something I’m really interested in and combining those two is exciting.

TL: You mention people who have traditionally experienced barriers to accessing special collections. What can you hope to gain from your experience here that might help inform improving the situation for people who experience barriers when it comes to special collections? You’re talking about working with researchers – they come in with a very much different attitude than students. If you layer on top of that, these sorts of barriers that affect underrepresented communities, how how do you expect your time here to inform how you might address that in your future work, especially if you’re planning on going back to special collections or spaces where those barriers still exist?

JT: I was a diversity scholar with the Association of Research Libraries. During my time in library school, I was put together with a group of other people from underrepresented groups. And one of the things I enjoy about about digital archives is that it’s new. It’s everyone’s starting from the same starting place. Everyone has photographs, everyone has videos, everyone has that. So where traditional archives are behind the paywall, with digital archives, we’re all starting from the same place. While I’m building the skills, I also have to learn how to adapt them so that people who are not traditionally trained in archives – because one of my focus is while I was in library school was in community archives and the techniques that they use – will have the access and skills to use these resources. Since digital archives is still a fairly new practice, it’s a starting place for everyone and you can gear an approach towards underrepresented groups, so that they can have this new tool to tell their stories and they’re not starting at such a distinct disadvantage.

TL: That’s a really interesting perspective. I hadn’t thought about that, but thinking about the difference between trained scholars and researchers versus students who may be digital native. The new digital landscape might actually start to tip that balance a little bit toward people who haven’t had experience in archives previously.

KS: I think for me, what I hope to gain from my time in terms of the way I approach librarianship when it comes to working with low income or underprivileged students is through my experience working with undergraduate students. That’s what I’m most excited about. I am first generation college student, I was the first one to go to a university, so it was an unfamiliar experience. Working with students and seeing how they think and how they perceive not only their library space, but their academic career, and being able to empathize – hopefully I can gain some understanding of how they use the space and use that knowledge to make the space for them. From personal experience, I went to one workshop as a first year in an archive that affected my whole career and that showed me that I could be a librarian, and then every time I meet other librarians of color who are ahead in their careers – like Rachel or like Albert – it’s like, ‘Oh, there are people of color and their doing really well in their field. I could do that, too, and hopefully I could have some type of impact.’

TL: Move ahead in time two years, what are you hoping to look back and have gained from your residency? What are some of the other intangible benefits that you want to gain from you experience here?

KS: I went back home for Thanksgiving, and I was thinking about what I’ve learned so far in the little time I’ve been here, and I realized I’ve been able to work really closely with Maria and I’ve learned so much just working the last few weeks with her. I’ve learned so much about how she carries herself as an assessment librarian. Also as being a co-chair of the Diversity Action Committee and how strong she is. I really admire that and working with (Digital Scholarship Librarian) Allyssa Guzman, and meeting (U.S. Studies Liaison and former diversity resident) Adriana Casarez and the previous diversity residents. I have been able to speak to them about my experience and learn from their own experience working at UT. Their advice has been very helpful in learning how to navigate my role. It really makes me excited to work closely with other people throughout my rotation because I’ve learned so much already, and I’ll be able to learn more and create fruitful relationships that I’ll be able to keep. I’m really excited to create those relationships and to understand how a bigger academic place like this works. Being here, learning about the organization and understanding that will benefit me once I move to a permanent professional position. Talking to Allyssa about people’s positions and how everything is structured has been really helpful because I feel like if I came in here as a librarian, I would feel intimidated to even ask those questions because I would feel like I should know this already, but as a resident, I get the opportunity to ask question and to learn how this library works.

TL: You’ve been working in academic libraries, and you’ve had some experience there. So how is it different for you then?

JT: Well, I’m not a student anymore (laughing). One of the things that Karina hit on that I’ve also noticed is that while doing these interviews, one of the things that – for lack of a better word – has been contagious is that everyone is so energized by the work and that’s one of the things I want to take away from this is not being the student actually but actually being treated as a professional. I want to come out of this feeling like a professional and that I have this subject knowledge, and that I’m able to apply that to other places. In most of the groups that I’ve interacted with, I’ve been a student and someone who’s preparing to be in the in the career. So now when I’m networking, I can talk as a professional and I have contributions to the conversation. That’s one of the things that I want to carry with me when I’m out of this residency program. I think that this is a great incubator for that because it’s a program that’s made to made to support you and make sure that you’re getting what you need. And I think that I think that we will be successful once we’re out of this program, but we’re also given time to explore, to realize what kind of information professional we wouldn’t want to be.

TL: Why is this program and programs like it important? Is it important at all?

JT: Yeah. I think, I think it’s really, really important. First, you’re able to rotate different areas, which something that I really like about. I don’t know if other diversity programs do the same way, how Austin does it. And I think it specifically focuses on people of color. I feel like when you see positions like that, you feel more motivated and you feel like you have more of a chance to succeed. And also it’s for people who have just gotten their Master’s and just graduated. So that’s another thing that makes you feel like you have more of a chance to hopefully get this than another librarian job where it might require at least 2-3 years of professional setting and you’re competing with people who have like many more years than you. It’s very important in that aspect. And it’s also important, in a critical sense, to think about the way you are perceived in this type of space, the type of impact you have. As people of color coming from a low income area, it’s not our responsibility to create the change, but if you want to, you have that power, and it feels a little less intimidating being in this position. It gives you a bit more sense of having a voice.

I think it’s important that we recognize that we are the two individuals in this position, out of all the people who applied. We were privileged to be in this position and that in some way we’re flag bearers. There’s a lot of talk in this field about the need for diversity and the need to have diverse perspectives and that as the two individuals in this position and also the other individuals who are in similar programs that it’s our responsibility to no bring the change, but to be the change. The point of being the flagbearer is to make sure in the future that there’s no need for a flagbearer, is that there’s no need for programs like this. So, the point of this program is to make sure that there is no need for programs like this in the future. We kind of have the responsibility to be the best professionals that we can and advocate where we can, because we are the we are the two individuals representing this program. We have to interlink with the other individuals who are in similar programs to make sure that there’s no need for programs like this in the future, because the field will already be diversified.

KS: And to piggyback on Jeremy’s thoughts – not to seem negative – but programs like this do have a performative activism to them, which is an issue. So, I totally agree with Jeremy that hopefully in the future we don’t need these kinds of programs because libraries are diverse enough or we don’t have to have this type of performative work to show that we’re diverse.

JT: Yeah. Speaking to the performative, I don’t really like public speaking, or, you know, talking to anyone – I would be more than happy to be in my dungeon doing my archival work, just be in this position. But I have to stand up, be counted. Like: Hey, I’m Jeremy Thompson. I’m the diversity resident and I’m in this position and I’m showing you my face. And that’s important.