Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from UTL’s Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship. Our hope is that these monthly reviews will inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

As readers, we often subconsciously craft physical spaces – whether real or imagined – in our minds in an effort to find meaning within or forge a connection with the text. The same can be said of the real-world cities in which different works of fiction take place. London, replete with a rich history of representation throughout the arts, is a standout example of one such city that writers return to time and again to inspire adaptations, reimaginings and original content. One need look no further than recent shows like Sherlock or Penny Dreadful to evince this. Keeping with this interest, researchers have created a tool that allows people to quickly and easily look back at those original texts that helped shape popular conception of London in the form of an interactive map of specific sites.

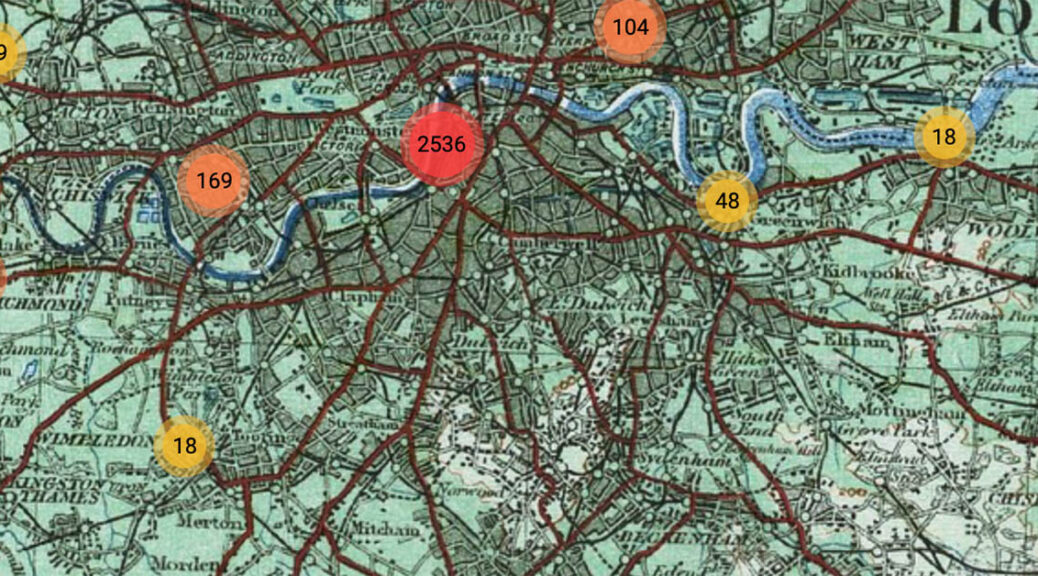

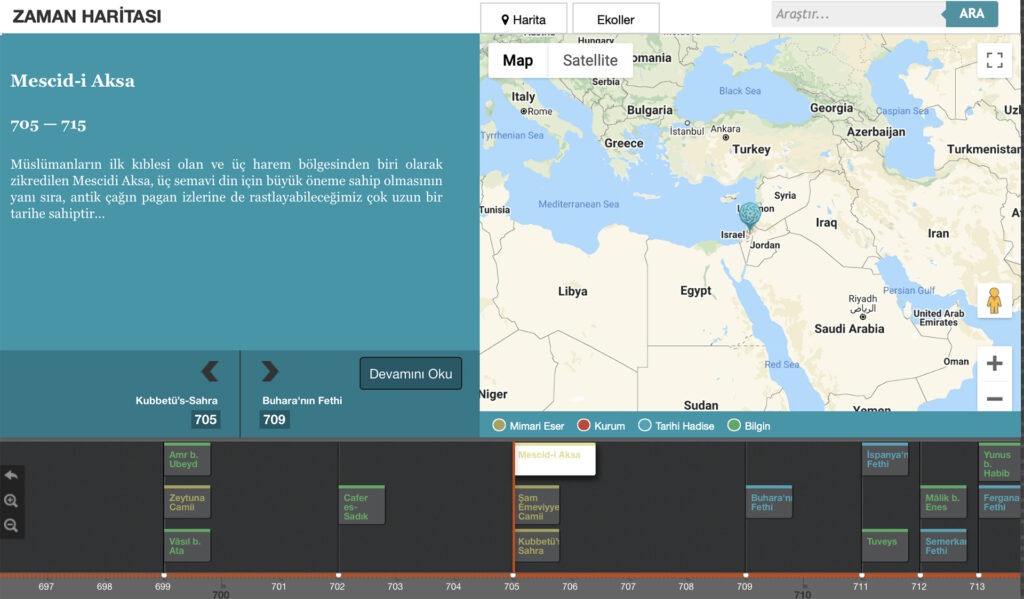

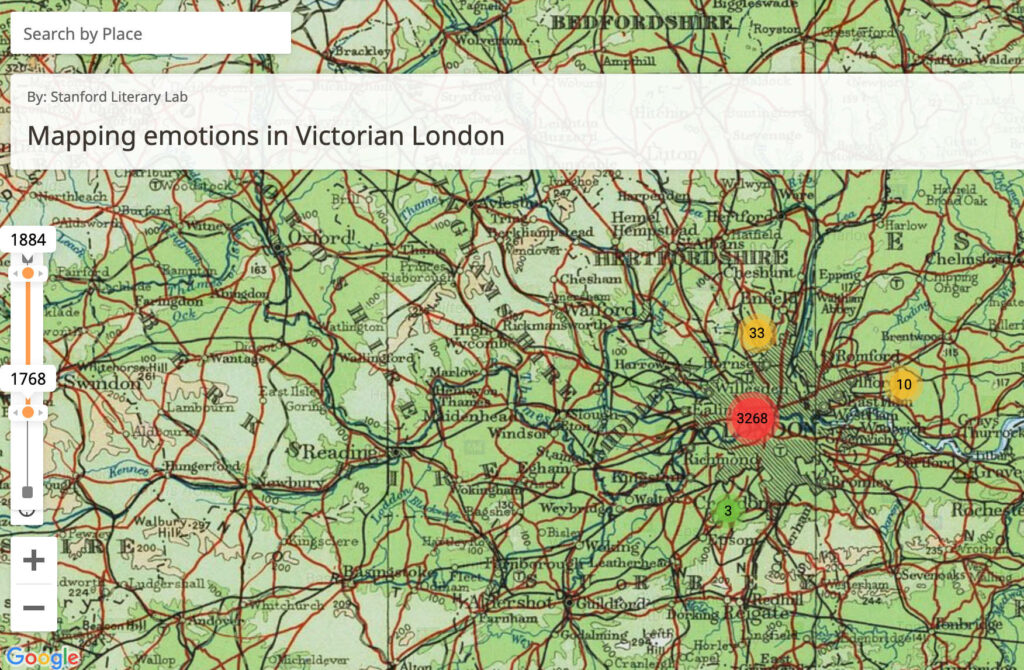

Mapping Emotions in Victorian London is a digital project created at Stanford University that uses literary excerpts from 18th and 19th century novels to map the emotions associated with different public spaces throughout London. The interactive map, hosted on History Pin, allows users to geospatially visualize data from those passages and read the excerpted passages in one streamlined interface. The map itself was created using Google Maps but features multiple levels of overlaid antique, illustrated maps, which shift depending on the scale selected, lending a visually pleasing touch to the tool without sacrificing utility or data integrity. Using it is as simple as selecting a date range and then clicking through numbered hubs on the map until you arrive at a particular site and the corresponding text.

Originally conceived as a small-scale project using topic modelling to extract geographical information from nineteenth century novels, “Mapping London” later expanded to encompass a collaborative effort between the Stanford Literary Lab, the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA), and the Mellon Foundation. Building upon the success of their preliminary efforts (documented in a 2016 pamphlet), the site developers received a grant tied to crowdsourcing that pushed the project to new depths. Anonymous volunteers used Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace to crowdsource the project by assigning emotions to the thousands of excerpted passages. The crowdsourcing aspect of the project is what took it to another level by allowing researchers to expand both the quantitative and qualitative methods used. Not only were they able to process vastly more information and include more sites and passages in the data set, but humans (rather than bots or AI) were able to accurately ascribe emotions to the text.

While the ultimate goal of the project was to expand possibilities for both close and distant reading research in the humanities, what stood out to me was how accessible and interesting the map would be to everyday readers including those outside of academia. For people new to or unfamiliar with digital projects, this is a very accessible and easy to understand collection. Furthermore, anyone pursuing a personal interest in specific sites in London, a particular author represented in the data set, or just intrigued by the concept of literary geography would have something to gain by exploring the map. It functions as a historical city tour through the eyes of different narrators, and might even introduce you to your new favorite author.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Explore further with UT Libraries!

Learn more about the concept of topic models in Ch. 9 of Foundations of Data Science.

Blum, Avrim, John E. Hopcroft, and Ravindran Kannan. Foundations of Data Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/be14ds/alma991058049444506011

Trace the connections between social production and London-focused literature and discover how the Bloomsbury district of London developed in relation to the city’s literary output.

Ingleby, Matthew. Nineteenth-Century Fiction and the Production of Bloomsbury : Novel Grounds. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

https://search.lib.utexas.edu/permalink/01UTAU_INST/apl7st/cdi_askewsholts_vlebooks_9781137546005

Take an in-depth dive into the world of literary spatial studies with Lisbeth Larsson’s investigation of London through the lens of Virginia Woolf’s oeuvre.

Larsson, Lisbeth. Walking Virginia Woolf’s London: An Investigation in Literary Geography. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2017.

Experience historic London firsthand through descriptions compiled in this fully digitized guide book from 1902, courtesy of UTL’s “Travel at the Turn of the 20th Century” digital collection.

Karl Baedeker (Firm). London and its environs. 1902. “London and its environs – Collections”. University of Texas Libraries Collections.

https://collections.lib.utexas.edu/catalog/utlmisc:40a94727-537b-46b1-b688-fe6b440bd2d8

If old books are more your cup of tea, check out the Harry Ransom Center’s extensive eighteenth- and nineteenth-century collections with works from many London-based authors, including Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Lewis Carroll, and many more.