Read, hot & digitized: Librarians and the digital scholarship they love — In this series, librarians from the Libraries’ Arts, Humanities and Global Studies Engagement Team briefly present, explore and critique existing examples of digital scholarship to encourage and inspire critical reflection of and future creative contributions to the growing fields of digital scholarship.

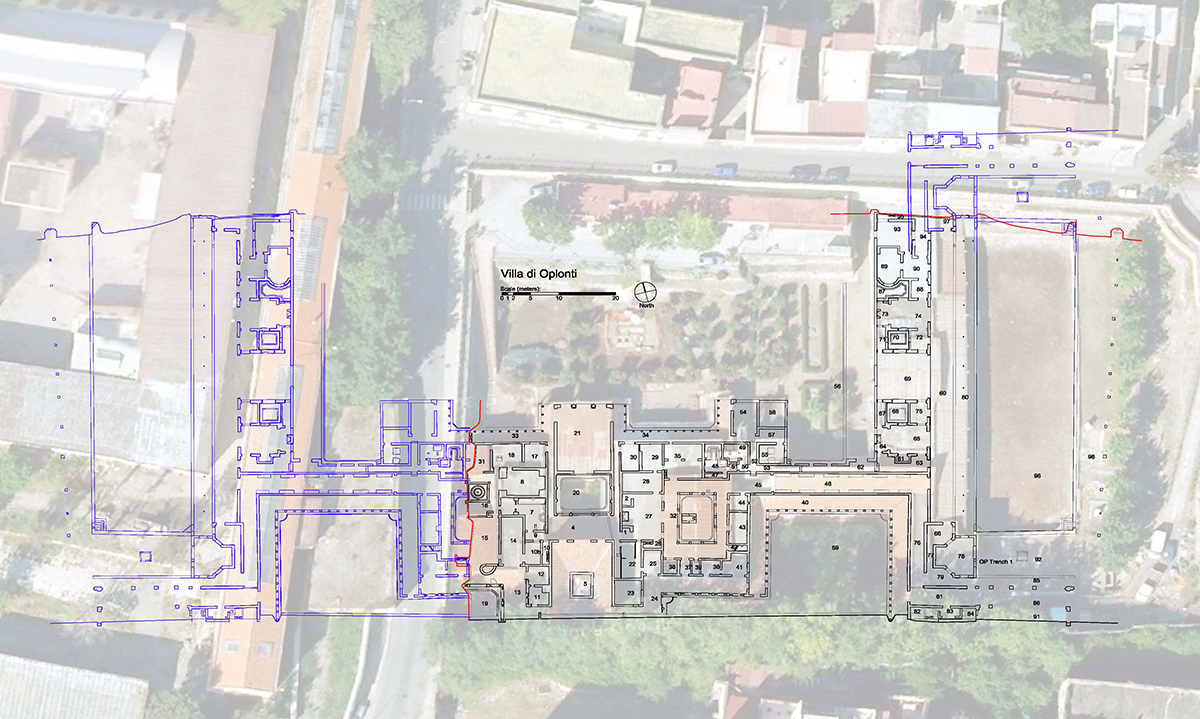

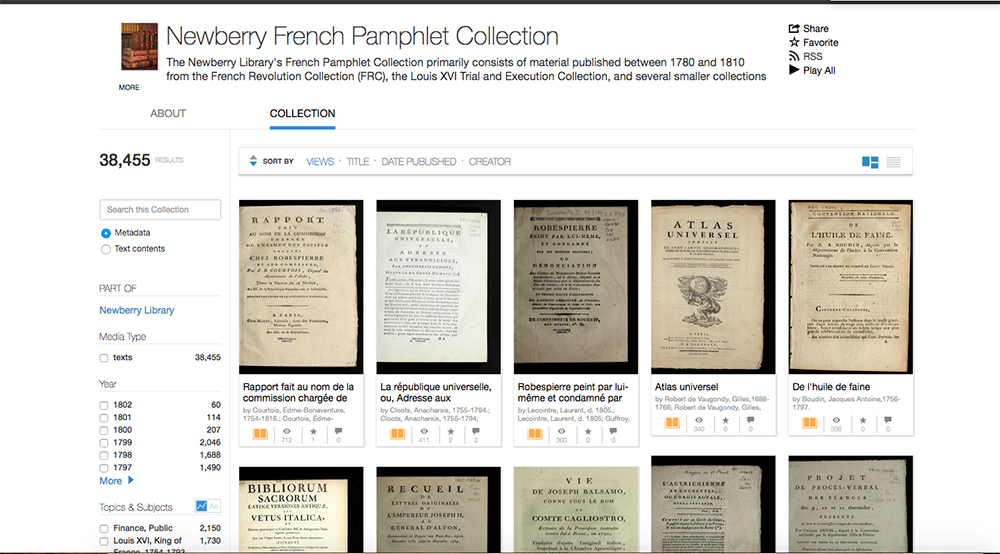

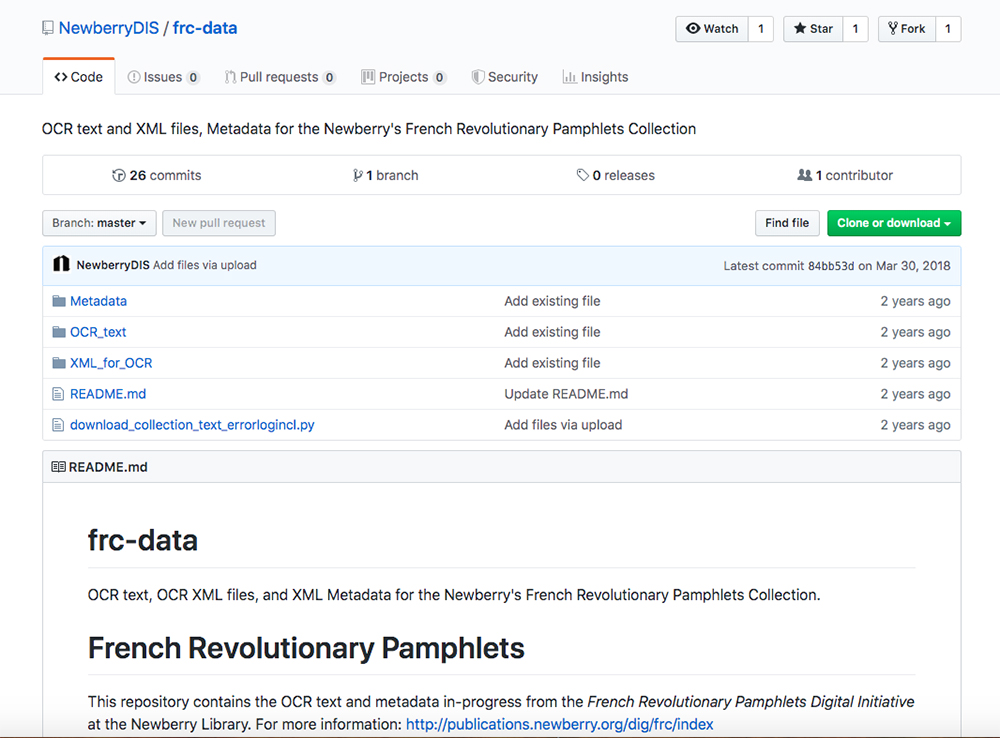

The French Revolution Pamphlets Digital Initiative, based at the Newberry Library in Chicago, is a large-scale digitization initiative that makes digital copies of over 38,000 documents, mostly pamphlets, accessible online. The documents, which primarily consist of material published between 1780 and 1810, encompass 850,000 pages of text, and the dataset produced by the project, containing OCR and metadata files, is roughly 11 gigabytes. This collection of French Revolutionary materials is among the most comprehensive in the world, and enriches the study not only of French and European history, but casts light on broader concepts of revolution and social transformation relevant to a global audience. The materials are of interest to numerous fields of study, including legal, social, and cultural history and the history of printing and publication.

The collection gathers materials from a number of the Newberry’s collections, including the French Revolution Collection, the Louis XVI Trial and Execution Collection, and several smaller groups of French Revolution era material. The materials chronicle the political, social and religious dimensions of the Revolution’s history, and include works by a diverse set of authors, including Robespierre, Marat, and Louis XIV. The texts include arguments both in support of and opposing the monarchy between 1789 and 1799, and serve as a firsthand chronicle of the First Republic. The collection includes complete runs of well-known journals, many rare and unknown publications, and about 3,000 French political pamphlets published between 1560 to 1653 that document a period of religious wars and the establishment of the absolute monarchy.

The main interface for the project was built in Scalar, a free and open source web authoring platform from the The Alliance for Networking Visual Culture at USC. The Scalar site links to the digital copies of the pamphlets, hosted on archive.org, as well as translations of select pamphlets. The sites also includes a number of other valuable resources, including data downloads, digital pedagogy materials, and pages designed for librarians interested in working with the digital collection.

To help support scholarship using the collection, the Newberry has funded an open data grant to support researchers working with the project’s large data set. The recipients of the first grant, Joseph Harder and Mimi Zhou, are conducting a sentiment analysis of the French Revolution materials, assigning numerical values to word-use in order to code for positive and negative tone across the data. By applying sentiment analysis to both the popular press and propaganda, Harder and Zhou hope to find trends in public opinion throughout the French Revolution, and to see how those trends shaped the revolution’s political outcomes.

The project serves as an important contribution to digital scholarship in European Studies. The sheer volume of the project’s digitized materials alone is impressive, but the variety of the resources it encompasses makes it particularly distinctive. Its venture into funding research using an open data grant—and the fact that its data set is openly available to anyone who wants to download it—is especially exciting, and I look forward to seeing the scholarship that results from making these materials freely accessible online. For those interested in exploring French Revolutionary materials in the UT Austin Libraries, I recommend looking through our extensive holdings on the subject, including our collection of pamphlets, both in print and on microfilm.