Friend of the University of Texas Libraries and Art History Professor Eddie Chambers has curated a collection of publications for a display in the reading room at the Fine Arts Library.

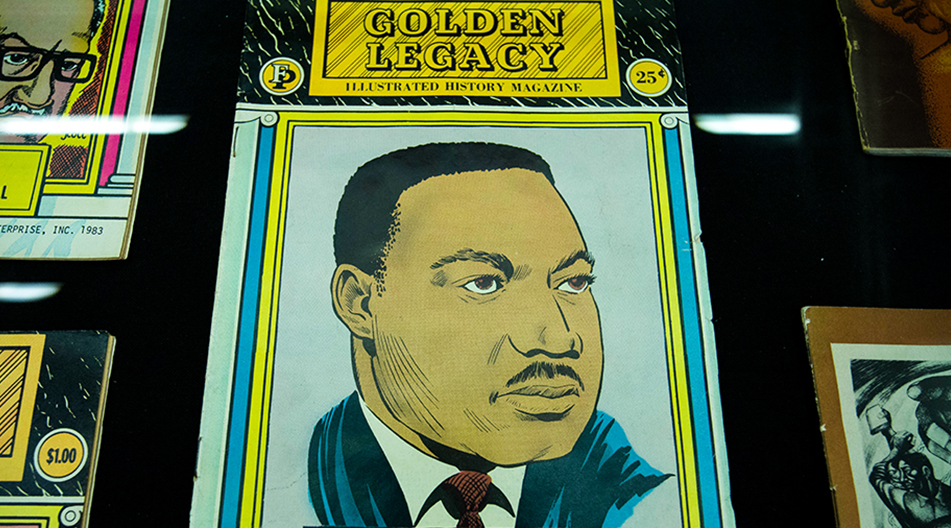

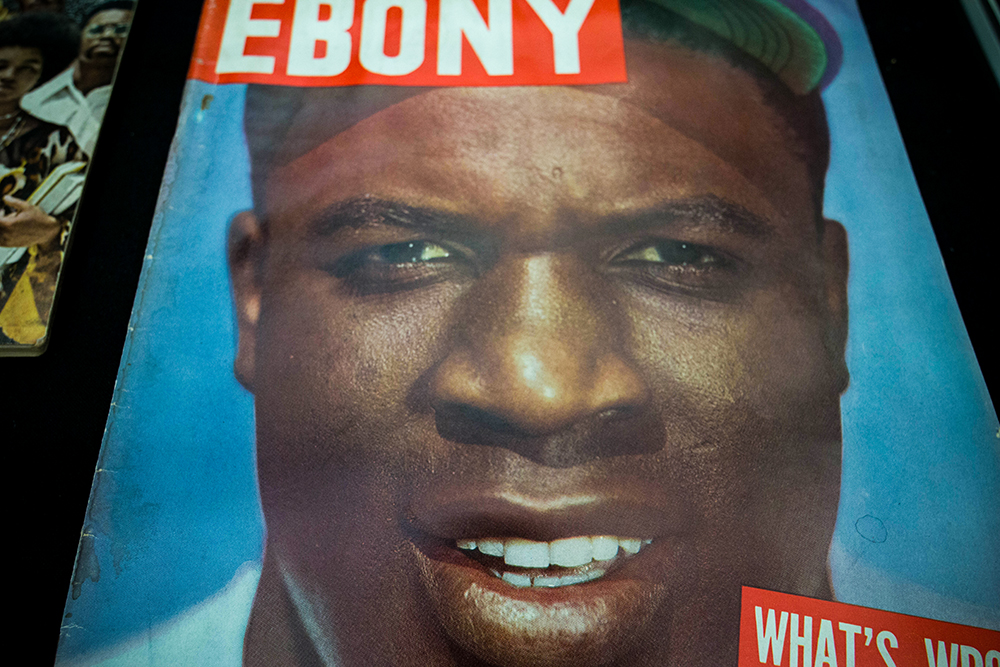

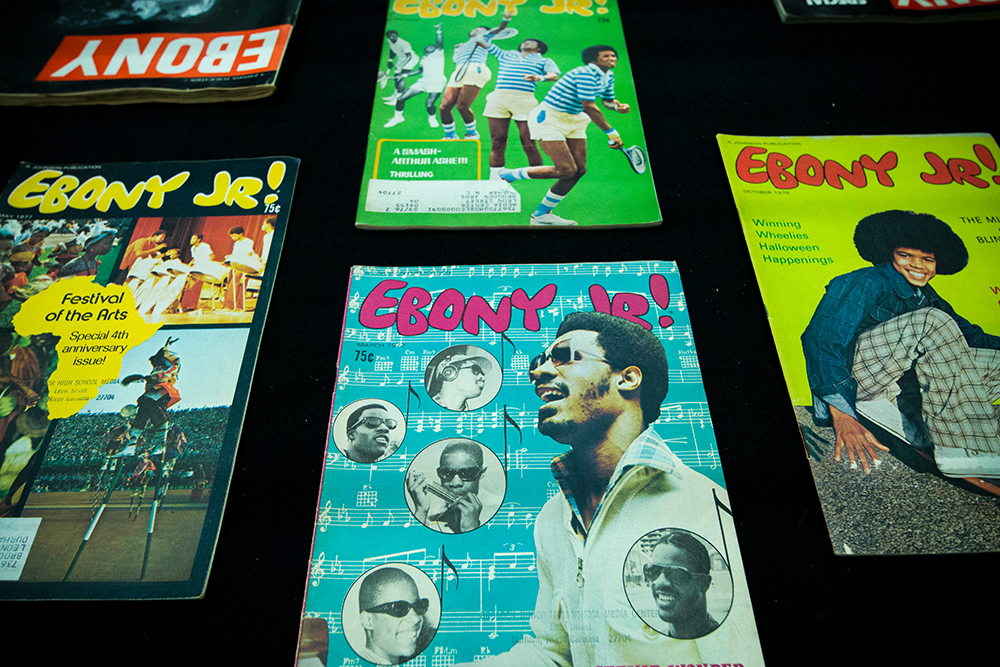

Chambers’ exhibit — “Recognizing the History of Black Magazine Publishing in the US” — features selections from his personal collection that represent the burgeoning of an independent press which spoke to the experience of African Americans in the late 20th Century, and includes examples from the period of the publications Ebony, Ebony Jr!, Jet, Black World, Negro Digest and Freedomways.

The exhibit is on display during regular Fine Arts Library hours through the fall semester.

What motivated you to curate the display?

Eddie Chambers, Professor, Art History: I have over the years collected, for research purposes, various magazines and journals, going back a number of decades. These magazines and journals have particular relevance to African American history, culture, politics, identity, and so on. Some of these I’ve assembled for the current FAL display. I am always attracted to vintage, archival items such as these as they enable us to get a direct feel, not only of the graphics and aesthetics of the times during which they were published, but in reading their texts, we get a direct sense of arguments, reportage and opinions, again, from the respective times.

As with so many things that carry an ‘African American’ prefix, we can perhaps trace the establishment of the Black press to a reluctance by the white-dominated media to pay proper and respectful attention to the agendas of African Americans. Magazines such as Ebony were important for a wide range of reasons including the readership’s ability to keep apprised of the ins and outs of Black celebrity lives, the ins and outs of the struggle for civil rights, going back many a decade, and the ins and outs of stories and issues that lay at the heart of African American existence. With the spectacular growth of the internet, the publishing media is in general, in various levels of retreat. This applies also to the Black press and the display points to the ways in which magazines published weekly or monthly were such an important and necessary means by which African Americans gleaned a wide range of information. And in Ebony magazine, the adverts are as entertaining as can be! It’s not hard for us to be inclined to the view that contemporary issues are different from those people thought about and acted on in decades gone by. Seeing magazines such as these, we might think, or realize, that issues we are concerned with or interested in at the present time, go back years, and decades.

Where are the materials from?

EC: I have collected the materials over the course of a number of years. Most of the material relates to some or other aspect of my research. For example, I recently acquired a copy of an Ebony issue that trailed on its front cover a feature on the quest for a Black Christ. Sourcing this came about because I am editing a volume – the Routledge Companion to African American Art History – which contains a text by a scholar, looking at visualizations of Christ and Christianity by African American artists. I wanted to double-check quotations by her, from this Ebony issue, in her essay. Material such as these magazines and journals are not frequently available to researchers and scholars, without considerable effort, so I find myself constantly sourcing such material. Having acquired items, I am always keen to share the material, which is why I periodically undertake displays such as this, in the Fine Arts Library (FAL). Right now, I have different archival material loaned out for exhibits that are currently on view at both the Blanton Museum and the Christian Green Gallery, here at UT Austin.

What do you see as the major impacts of the selected publications?

EC: The types of materials on view represent some of the sources African Americans had to turn to, in order to read stories that reflected themselves. Television was of course very poor at offering anything that was not considered of primarily mainstream (i.e. white) interest. Black publishing — and the adverts it carried — offered a vital route through which African Americans could source hair care products or, more generally, see adverts that featured people who looked like them. The importance of this cannot be overstated.

These magazines were also an environment that stimulated and gave work to Black journalists at a time when the mainstream media was frequently reluctant to. Photographers, typesetters, journalists, sub editors, layout artists, etc., all professionally benefitted from the Black press. We might think that in the modern age, people’s attention spans might be somewhat skewed or compressed, but the stories presented in some of these Black magazines enabled substantial, engaged, complex stories to be told, as well as the lives, loves, and ups and downs of Black celebrity life, to be digested. Of course, a pocket-sized magazine such as Jet offered its readers information in decidedly bite-sized chunks.

The perpetual, systemic framing of African Americans within the white dominated media was one of them as being ‘problems’. African Americans tended to realize that the framing of them as having problems was but a short hop skip and jump away from them being problems. The formidable perception, framed and maintained by the white controlled media, of America having first, Negro, then Afro American, then African American problems was more than enough to persuade African Americans of the need to maintain, for their own sense of self, a Black press that respected the multi-dimensionality of their selfhood. The Black press enabled African Americans to see themselves not as cardboard cutout problems, but as complex human beings who existed in the round.

Of course, it must be added that African Americans relied on the Black press to carry nuanced, informed analyses of the problems they had. In this sense, a profound manifestation of empathy existed between the Black press and its clientele.

How did this era of the Black press influence the representation of African Americans in modern media?

EC: Modern media is of course vastly different from publishing in decades gone by. One of the biggest influences is perhaps the ways in which white-controlled media has diversified, to an extent, its content. Quite rightly, we expect the New Yorker, the New York Times, and a slew of other media to carry stories that speak to the country’s diversity, including of course, that of the African American demographic. Diversified media content has in its own way perhaps worked to lessen the impact and importance of a distinctly African American branch of publishing.

There is of course still huge amounts of work to be done, but at the present time, the wholesale exclusion of African Americans from mainstream media, as was the case in decades gone by, is arguably less of an issue at the present time.